Central America/Jamaica/05.06.2018/Source: www.jamaicaobserver.com

Jamaica’s education system has followed a rocky road from as far back as we can check our history. This is not to say that the road does not have its smooth spots, but it is only in minor sections that we can feel the satisfaction of a system at work which is successfully producing good results on a sustainable basis.

It may seem that this is an exaggeration. It is not. How else is it possible to describe an education system that produces some 75 per cent failures in its graduating class year after year? Worse than that, 38 per cent of the age cohort are not even allowed to sit the exams for graduation, being considered too weak academically to achieve even the most minimal results.

From another point of view, the education system is an enigma. Many of those who qualify from the secondary school system and go on to tertiary education have turned out to be outstanding scholars who have consistently contributed much to national development. Some have even achieved international acclaim, and the best of our education system can stand up to international ratings.

But judgement of society is not concerned about safe landings. It’s about crashes. The education system speaks volumes to the frustrations and failures which make it dysfunctional. Yet, despite these obstacles, the system is too crucial to be allowed to exist in a state of bewilderment.

Generally, I approach problems logically and there is much to be gained by viewing education in this way. Reading through the insightful analysis of the brain in the Pulitzer Prize-winning work Inside the Brain, by Ron Kotulak, nearly 15 years ago, gave me a whole new perception of the earliest years of life and the impact of early childhood education.

The brain is examined as an organ which begins as a blank slate, gathering and processing an awesome collection of information by stages of complexity which allow children to grow in knowledge progressively. Scientific findings indicate that the growth period of the brain ceases at around seven years of age, leaving the child to work essentially with the size and capacity achieved at that time for the rest of his/her life.

This sounds frightening, but it does not mean that learning stops at that time; it only means that the ability of the brain will be limited in the future to the capacity it has acquired in the first seven years of life and the process of learning will only be more difficult, but certainly not impossible.

This puts the spotlight on those first seven early years as being of prime concern. Early Childhood Education (ECE) must then be the priority. In fact, it sets the stage for success thereafter as the support base for further education — just as the first layer of a three-layer cake is fully dependent on the ability of the bottom layer to support the top two. A weak first layer will expose the top two to weaknesses, failures and possibly some collapse, as is the case in the education system.

To reposition the early stage of education would logically require much more funding. Over the years, Jamaica has spent far less on education than is the case for many other English-speaking countries (Caricom) of the region. This led me to focus my own parliamentary efforts on a call for the reform of early childhood education, to strengthen it as the base — to the extent that, in 1997, I devoted my presentation in the budget session entirely to that subject.

Unfortunately, the budget was presented by the Opposition at the Jamaica Pegasus hotel that year because of a dispute with the then Government. As a result, in the budget session of the next year I presented the same speech again, giving the subject matter double exposure but also to get it in the official parliamentary record for future reference.

I continued what I considered a mission to promote early childhood education for the remainder of my parliamentary years until I retired in 2005. But to realistically do so, I also had to call for increased financing for the system. With Government under-financing the education system by providing only some 10 to 12 per cent of the national budget (this was the figure up to a few years ago), compared to 15 per cent and more in many other Caricom countries, I called for an increase of one per cent per annum for five years, starting November 2004.

My resolution to Parliament to this effect, together with a number of other educational reforms, was accepted by both sides of the House. I am not aware if its financial target has been met. To me, the most important objective in creating a rational, functional education system is to create a well-funded early childhood layer capable of giving a good start.

But another consideration has now been added by me which is even more important, particularly since it requires no additional funds, nor does it require any considerable period of time to accomplish.

Sometimes, the greatest benefits can come from the simplest changes in seeking solutions to problems. The most critical problem facing education is illiteracy. It holds the key. For decades the education system has recognised that illiteracy is a deep-rooted fundamental problem. Without literacy, learning is impossible. Yet, faced with this undeniable truth the system has been crawling for generations to adjust to meet this awesome challenge.

The readiness test administered to grade 1 entrants to primary schools has repeatedly shown that only 25-30 per cent of entrants are ready to receive formal education at the entrance levels. This was precisely the case half-a-century ago when the secondary school system was opened to secondary schools on a broad basis. Five years after that, Edwin Allen, minister of education, had to devise a unique way to give primary school graduates a secondary education by changing the admission policy.

It was decided that 70 per cent of all entrance places to secondary schools should be reserved for primary school students. This could have the most far-reaching effect on the future capacity of the country to grow and prosper. However, it was discovered that at 12 years old these new students, as in the case of entry to primary schools at six years, could not cope with the educational requirements. Indeed, many were barely literate.

That was decades ago yet the problem remains until today, with the majority of primary school graduates being low achievers. This should not be surprising as 60 per cent in the grade 4 National Literacy Test for 10-year-old students have repeatedly demonstrated various weaknesses in coping with reading and writing at this advanced stage, although this low figure is showing slight improvement now, thus leaving them unable to deal with secondary education. This would not have been the case had this percentage of students been literate.

This is a new road for education, one that challenges us to think outside of the box. For centuries we have travelled the same failed course; time now to travel a different path, to try something new.

The day has come at last. I was thinking that it may never happen after so many years of speaking and writing about the critical need for Government to take over the basic school system so that it could handle the transformation of these schools which have been neglected for so long. Recently, the Minister of Education Ruel Reid announced that Prime Minister Andrew Holness has agreed to that proposal. This is an excellent move.

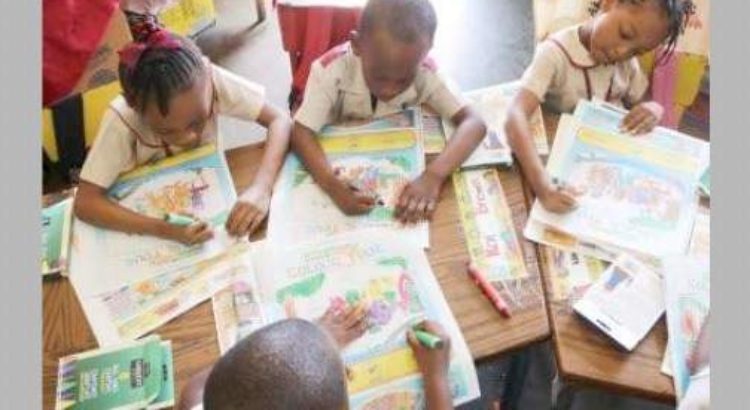

Generally, many persons think of these schools for little children from three to five years old as “play-play” schools, where their little ones can be parked in the day under the care and protection of teachers.

But parents are not aware that this is a vital stage in the education system. Children who are not educated at this stage can fail miserably, in later years of schooling, to be sufficiently educated to get passing grades when they leave secondary school without graduating.

The reason for lack of appreciation is as a result of little understanding of the role of early childhood education and what it can achieve when it is taken seriously. The seriousness of this phase of ECE is that it is the foundation of all education, because it is the beginning of the education of the child. If you are building a house you have to start with the floor, not the rooms, nor the roof. ECE provides that foundation.

Failure to put this opportunity to use by enrolment and regular attendance is a trap many people fall into, out of ignorance or the lack of care. The result is, children who go to primary school eventually at six years old have to keep up with other children who received ECE for their first step in education and have become acquainted with the early stages of reading, writing, numeracy, social and cultural activities, among other areas of learning.

In the first grade of primary school, who do you think the teacher is going to focus on? The children who have participated in the ECE progamme who can follow what is being taught in grade 1 to prepare for grade 2, or the ones who lack the education which should have been received as the first step of the ECE? The teacher is naturally going to focus on the children who are better able to enter grade 2.

The children knowing too little about what is going on because of knowledge deficiency are naturally left behind. And so it continues in each grade thereafter as the gap widens, focusing on those who can learn while leaving those who cannot further behind. Each grade will suffer in the same way, producing students who have learned and those who have not.

This stream flows right through the system until at graduation the ratio is still, more or less, the same: 30 per cent who have benefited from early schooling and can graduate and the seventy per cent who have not and cannot [graduate]. That is what we have to build a nation — a minority who are skilled and find employment or become gainfully self-employed, and a sizeable majority who have no skills and who, even if they find some hustling or unskilled work, will not be able to even keep themselves. This will continue to be our future if significant improvements are not made.

There is still one more step in this critical pathway to failure when those who fail cannot, as adults, pay water rates, electricity rates, taxes and other such basics of life. The costs of these have to be carried by the minority who are skilled by training. Prosperity for the nation won’t come until far more students go through comprehensive schooling and training. The ratio then could be reversed to 30 per cent failure and 70 per cent passes. This would produce more of each category of skills. Then we can build a nation.

To this major undertaking must be added properly trained teachers of which the minister says there is now one per school. Completing this programme will provide the necessary opportunities for the development of real prosperity.

What are the steps to accomplish this?

• Special financing would be needed. I have already proposed that the National Housing Trust (NHT) needs more educated adults in the society to be able to deal with more mortgage financing, as it has admitted, to increase the housing stock and provide more homes. The NHT has a surplus of some $20 billion a year. It can spare $2-$3 billion per year and still increase its surplus annually.

• Increased teaching staff. This could be programmed by arranging facilities by training in teachers’ colleges and in the HEART Trust/NTA over a number of years.

• Increase the sources for equipment for ECE schools. I started a programme which I called Programme for the Advancement of Early Childhood Education (PACE), which I proposed to use to get the Jamaican Diaspora involved by asking groups with enough involvement in the community affairs of Jamaica to undertake to obtain equipment — new or used — overseas for the ECE schools. This is a project which would be able to fit in with their own interests since on a number of occasions the Diaspora has shipped to schools in Jamaica, furniture and equipment obtained from replacement in schools in their areas abroad.

In my visit to Toronto in 1988 to start the programme, I found a number of Jamaicans who were interested and were willing to serve in such an organisation I called PACE of Canada. This group has worked out very well for the past 30 years, with shipments arriving regularly. I had hoped to establish many more PACE units in the USA, Canada, and Britain but the Government was changed in 1989 and nothing further happened.

We are thankfully on the way now with one of the most important projects for building a prosperous nation in which all could learn to earn, and earn to learn.

With the changes in the early childhood education system, we are on the way to helping those who are caught in the deficiencies they now face to find a way out. As I have often said in a quote which I coined: “There is no country that is uneducated that is rich and no country that is educated that is poor.”

The time has come to take a giant step into the future. Time to move now.

Source of the news: http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/news/education-the-missing-ball-in-the-competition-for-growth_134780?profile=1096

Users Today : 120

Users Today : 120 Total Users : 35403313

Total Users : 35403313 Views Today : 156

Views Today : 156 Total views : 3332595

Total views : 3332595