Por: Ruth Maclean / The Guardian

-Un viaje hacia el corazón de Costa de Marfil muestra cómo sus bosques están siendo destruidos para abastecer la creciente demanda mundial de chocolate.

– La industria del chocolate lleva al desastre a los bosques tropicales de Costa de Marfil, como contaba eldiario.es en su especial La Tierra Esclava.

Desde el verde paisaje del parque nacional de Marahoué se alzan fuertes árboles plateados, con lisos troncos que únicamente lucen ramas en su parte más alta. Marahoué es uno de los ocho parques nacionales de Costa de Marfil. Hace 20 años estaba cubierto de bosques y era el hogar de chimpancés y manadas de elefantes.

Hoy en día es más común ver el esqueleto de unos árboles que fueron quemados lentamente para librarse de la sombra que proyectaban sobre los campos de cacao. O simplemente unos tocones aserrados.

Henri, líder tribal en la cercana ciudad de Diafla, creció junto al bosque y habla con cariño de sus imponentes árboles de iroco. Pero él también participó en su destrucción. Como tantos otros, Henri tiene plantaciones de cacao dentro del parque y emplea a personas de Burkina Faso para trabajar ahí.

“Todo esto estaba cubierto de árboles, pero los agricultores los quemaron para plantar cacao”, dice. Cuando Henri era joven, solía ver chimpancés y elefantes caminando por el parque. Ahora los animales han sido reemplazados por personas.

Como se le acabó el combustible de camino a Marahoué, Henri ha dejado su motocicleta cerca del camino y está terminando a pie su viaje. Pasa cerca del ganado, de las omnipresentes y deshilvanadas plantas de cacao y de los restos de un albergue turístico destruido en 2008, poco antes de que se fundara la cercana aldea de Zanbarmakro.

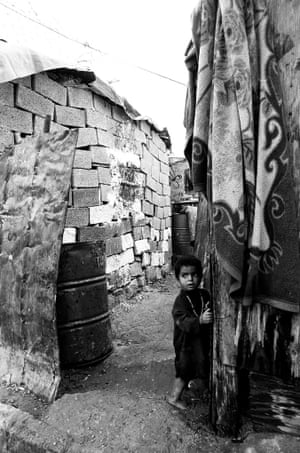

Poblaciones ilegales

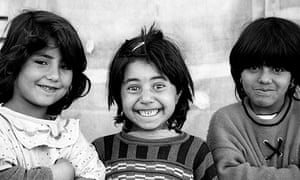

Nadie utiliza la palabra “aldea” para referirse a Zanbarmakro. Prefieren “campamento”, que suena más pasajero. Pero la enorme iglesia construida en un extremo y la mezquita al otro, así como los hogares, las tiendas y la clínica privada disipan cualquier indicio de que este lugar, habitado por 13.000 personas, no vaya a estar aquí por mucho tiempo.

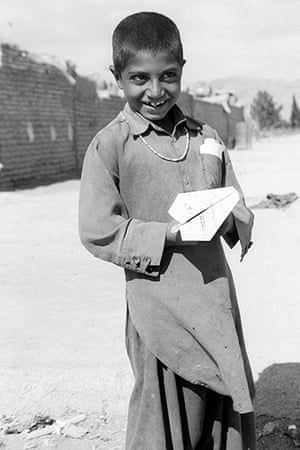

Los hombres llegan desde las plantaciones en sus motocicletas a media tarde y descansan en las escalinatas de una tienda de refrescos. Las mujeres despliegan su mercadería: una mujer exhibe una pila desordenada de calzados; otra, un estante con guadañas, de esas que todos los niños llevan para cosechar. Zumban los molinos de yuca. Según algunas estimaciones, hay 50 aldeas ilegales dentro del parque. Zanbarmakro es de las más grandes.

En la entrada hay un puesto de vigilancia soportado por pilares construido hace años por la OIPR (Oficina de Parques y Reservas de Costa de Marfil), la autoridad estatal de los parques. Los guardaparques de este organismo tienen el deber de garantizar que no se tale ningún árbol, que no se cace ningún animal silvestre y, por supuesto, que no se construya ninguna aldea dentro del parque. Extrañamente, parece ser que no se percataron de la llegada de los ladrillos y el cemento utilizados para la iglesia y la mezquita, ni de la salida de camiones cargados de madera y granos de cacao.

Henri presenta a Zoughory Laji Bourema, el jefe de Zanbarmakro, que camina alrededor de una gran lona blanca sobre la que está secándose el cacao para llegar hasta el porche. “Tengo algunos problemas con la OIPR”, admite Laji Bourema, alisando su brillante bubu violeta (una especie de túnica que visten los hombres).

Tarifas de soborno

Los guardaparques de la OIPR pasan la mayoría de su tiempo bebiendo té y revisando el WhatsApp en la residencia detrás de la oficina, a pocos kilómetros de los límites del parque. De vez en cuando, sin embargo, salen para ir “de caza”. Aparecen en alguna de las plantaciones, arrestan a varios agricultores todas las semanas y los dejan encerrados hasta que la comunidad paga por su libertad. El precio de los sobornos es conocido por todos: 100.000 francos (152 euros) por persona, o 150.000 francos (228 euros) si los encuentran con una motocicleta.

“Vienen a las aldeas, recogen el dinero, unos millones de francos cada vez, y luego se vuelven a ir”, dice Henri, buscando en vano la sombra de un árbol para protegerse del sol. “Vienen unas dos veces por mes a buscar dinero en sus todo terreno”.

La gente del lugar dice que el soborno que tuvieron que pagar en mayo fue más alto que nunca: equivalente a 16.800 euros entregados al jefe de la OIPR local. (La petición que hicimos para hablar con el jefe de la OIPR, el coronel Tondossama Adama, no obtuvo respuesta).

A cambio los dejan quedarse y cultivar el cacao, que venden a compradores en las ciudades cercanas de Bouaflé y Bonon. Estos intermediarios lo venden a su vez a Saco, una subsidiaria de Barry Callebaut, que provee de cacao a varias marcas internacionales de chocolate.

Cuando pedimos hablar con la empresa, Barry Callebaut no negó específicamente la acusación de que haya cacao producto de la deforestación ilegal en su cadena de suministro. “Hay cultivos de cacao en áreas con un alto valor de conservación en África Occidental”, dijeron. Barry Callebaut volvió a reafirmar su compromiso de terminar con los productos de deforestación para el año 2025.

Ilegalidad en las cadenas de producción

El periódico the Guardian viajó por Costa de Marfil junto al grupo ambientalista Mighty Earth para investigar el impacto del cacao en los cada vez más escasos bosques tropicales. Ambos entrevistamos a comerciantes y directores de cooperativas que dijeron comprar el cacao en áreas protegidas para vendérselo a Olam, una empresa agrícola mundial. Olam reconoció un incidente que según la empresa había sido aislado y añadió que había puesto en práctica varias medidas para garantizar una cadena de suministro limpia.

“Olam tiene absolutamente claro que la deforestación hecha por los pequeños agricultores de cacao debe terminar”, dijo un portavoz antes de añadir que, de todas formas, “se trata de una cadena de suministro compleja y altamente fragmentada”: “Las dificultades para rastrear el cacao hasta cada pequeño agricultor son inmensas”.

En el campo de cacao de un comprador llamado Sivacco, en la ciudad de Man, los hombres cuelan los granos en tamices metálicos rectangulares y con palas los meten en talegas. Uno de ellos tiene puesto un sombrero de Papá Noel. Frente al campo hay un extenso aserradero lleno de pilas de serrín, tablones y troncos. Por detrás se ve cómo sube el humo.

“Desde luego que nos llega cacao de las reservas forestales”, dice el jefe de almacén, que prefiere no ser nombrado. “Los pisteurs (motociclistas) lo traen hasta aquí y nosotros no sabemos exactamente de dónde viene. Vendemos a todas las grandes empresas”. Detrás de él hay un mural que incluye el símbolo de la Alianza para Bosques y una lista de actividades prohibidas.

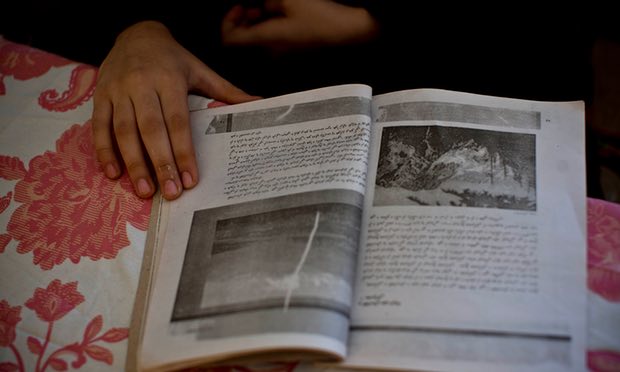

“No nos importa. Ni siquiera preguntamos a los productores de dónde viene el chocolate. Las grandes empresas tampoco preguntan nunca de dónde viene”, dice Bamogo Arouna, un comprador de la ciudad de Taobly, en la base del monte Tia (un bosque de acceso reservado en el oeste de Costa de Marfil). Arouna dice vender a dos grandes exportadores que a su vez venden productos derivados del cacao a empresas como Nestlé, Mars y Hershey.

Los agricultores van en sus bicicletas cargadas de cacao desde la reserva hasta la bodega de Arouna, desde donde sale el empalagoso olor a cacao crudo. Paradójicamente, no se parece en nada al del chocolate. Un agricultor baja una talega de cacao a medio llenar del portaequipajes de su bicicleta. Los otros vierten su contenido dentro de los enormes tamices.

“El cacao es el cacao”, dice un comerciante encogiéndose de hombros y mirando el frondoso paisaje delante de él. “Nosotros solamente pagamos a quien lo tenga. No hacemos diferencia entre las reservas forestales y las no forestales”.

Hace doce años, cuando llegó a la zona, proveniente de Burkina Faso, la vista era la de un bosque tropical. Hoy todo son cultivos. Para él, no hay diferencia.

“Cuando llegué, era verde”, dice el agricultor. “Y aún lo es”.

Traducido por Francisco de Zarate

Fuente: http://www.eldiario.es/theguardian/precio-cacao-destruyendo-bosques-chocolate_0_686982015.html

Users Today : 105

Users Today : 105 Total Users : 35402654

Total Users : 35402654 Views Today : 127

Views Today : 127 Total views : 3331747

Total views : 3331747