By: Bitasta Das.

This year, I am teaching the sixth edition of the undergraduate humanities course “Mapping India with the Folk Arts.”

In this course, we delve into indigenous knowledge, or common people’s knowledge, focusing on a different form of Indian folk art every year. By understanding the variations of this art across the country, we explore, infer and map cultural continuity and diversity. The assignments given to the students form an important component of the course, and it is through these assignments that a dialogue is established between science and art.

Having conducted this experimental course for a significant amount of time, I thought it was a good time to look back and reflect on the intention, process and outcome of the course so far.

Humanities subjects were incorporated in the academic curriculum of IISc from 2011, when the four-year undergraduate bachelor of science (BS) (research) programme began. The Centre for Contemporary Studies (CCS), under Raghavendra Gadagkar, assumed responsibility for designing and teaching the humanities curriculum. Students compulsorily undertook to learn humanities subjects in six out of the eight semesters of their BS programme.

While the conceptual thread across the courses remains the same, the humanities curriculum is designed to introduce the students to an array of disciplines and methodologies within the social sciences and humanities. Unlike in other science and technological institutes, the curriculum does not attach the humanities courses as disconnected subjects, rather, they are composed to provide a socio-cultural background to learning and understanding science.

Taking this philosophy forward, “Mapping India with the Folk Arts” treats the art of the common people as windows to their way of life. Drawing from the discipline of Folkloristics, the aim of the course is to understand the country, not from the outside in, but from the inside out.

As for my own education, folklore formed a large portion of my studies for a master’s degree in cultural studies at Tezpur University (Assam), and I qualified for the University Grants Commission’s National Eligibility Test (UGC-NET) in folkloristics. My first job in Bengaluru at the Art Resources and Teaching Trust (while I was pursuing my doctoral degree on ethnic identity and conflict), was to manage and commission an art exhibition involving 65 folk artists from across the country.

Travelling to various pockets of the country for two years, meeting and interacting with indigenous artists, gave me practical exposure to the dynamic world of Indian folk art.

When Prof. Gadagkar asked me to design and teach a course, I decided to offer a hands-on course rather than a theoretical one. I turned to my experiences with the folk arts, but was initially apprehensive about teaching a course of this nature here. I was not sure if at IISc, where cutting-edge scientific research takes place, a course on common people’s knowledge would be welcomed. I was anxious that the folk arts would be taken too lightly, as a mere source of amusement.

My intention was to invoke and engage with the arts to sensitise the students to the values of diverse people. I lay out the course to the students as follows—a “folk” is any group that expresses inner cohesion by sharing common traditions, whether the connecting factor is language, place, ethnicity or occupation.

In this sense, a group of scientists is also a folk group! India, with its multicultural populace, is home to a wide range of rich folk art traditions. To understand the nation, we must understand its people. The category “folk” provides an agreeable premise for appreciating various kinds of people that the category “citizen” is unable to include, like diaspora, refugees, nomads, people who are displaced, and so on.

Since we take up a different folk art form every year, it is imperative that I keep finding new study material. The methodological approach and teaching also varies every year, though the assignments always focus on the interaction between science and art. If enquiry in the field of art and science is rare, works on folk art and science are even rarer.

The folk art of this country has a large vocabulary, yet the processes of science have never been its subject. I decided that the students, who have enough scientific understanding, could deploy folk art to create pioneering art works. I create the theme, which they have to deliberate on and represent.

Every year, we discuss beforehand how folk arts entail skills that are passed on within families and communities for generations and generations, and folk arts are as much about the artists as they are about the product itself.

To claim that first-timers trying their hand at it can excel in the art would be grossly wrong. But it is the beauty of folk art that it is not standardised or codified. We can work in that flexible space, and explore what we generate. And it often comes as a surprise to the students when we are discussing a folk art from their region, and they realise they have been completely oblivious to it.

Sometimes students see it as a “homecoming” to create art works from their region that they only know of, but have never tried to understand its intricacies. In class, we also discuss questions like these: Can common people make sense of the workings of science? Can art represent science effectively?

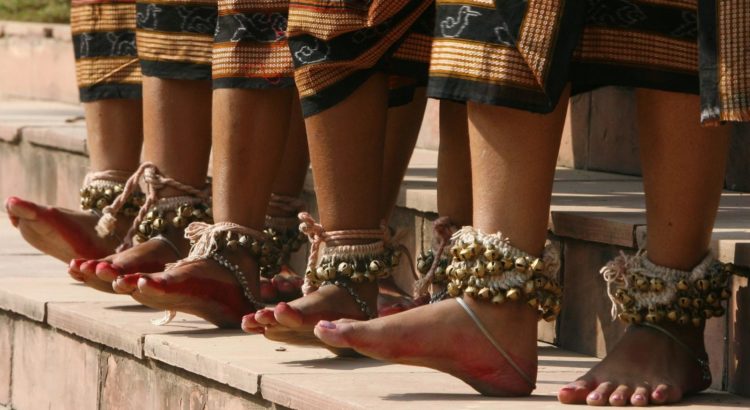

In their assignments, students have to use folk arts to present complex scientific concepts. Paintings, music, plays, and dances about science, using folk vocabulary, have been created so far. Workshops on Dollu Kunitha, kite-making, and Chittara art have been conducted. Public performances like “Folk Theatre Festival,” “Sway with Science,” and “Jal Jungle Zameen and Science” were put together by the students.

A pictorial book, Arting Science, published by IISc Press, compiles the paintings that were made. Another book, Jal Jungle Zameen… in the age of Science and Technology, is in the works. The Institute has earmarked a distinct section on its official website to showcase the students’ art works, under the category “Arting Science.”

The assignments are planned consciously so that the creations are not just objects of communicating science, but both science and the folk arts demonstrate their tenability. The students are told that their works are not primarily for securing marks but are opportunities to co-create novel art.

The course has demonstrated creative ways of expressing science, at the same time, a new realm of content has been opened for the declining folk arts of the country—that of science and technology. The media has lauded this pioneer course at IISc and has frequently reported on our activities. This year the focus is on Indian folk tales, and we examine how the country can be understood by these stories.

This year is significant for another reason too—CCS has been reconstituted to form the Centre for Society and Policy (CSP), headed by Anjula Gurtoo. Humanities courses from now on will be conducted by CSP.

There are numerous examples where indigenous values and knowledge have enabled communities to live harmoniously with nature and with one another since ages. It is my argument that in the present times, when sustainable modes of living are sought, the philosophical foundations that inform community life calls for a deeper understanding.

Every batch of students has contributed to unfolding this understanding. Our efforts in treading untraveled paths have been filled with wonder and have been deeply enriching.

And for me, personally, it is satisfying to be able to work with the arts of India. It is saddening that so many of them are fading—they are soulful and bear the essence of the country. Discussing, engaging, and creating with them in a space like IISc gives them a new lease of life.

Source of the article: https://qz.com/india/1653995/an-iisc-bengaluru-teacher-is-mapping-india-with-folk-arts/

Users Today : 22

Users Today : 22 Total Users : 35404289

Total Users : 35404289 Views Today : 29

Views Today : 29 Total views : 3333803

Total views : 3333803