By: Henry Giroux

George Orwell warns us in his dystopian novel 1984 that authoritarianism begins with language. Words now operate as «Newspeak,» in which language is twisted in order to deceive, seduce and undermine the ability of people to think critically and freely. As authoritarianism gains in strength, the formative cultures that give rise to dissent become more embattled along with the public spaces and institutions that make conscious critical thought possible.

Words that speak to the truth, reveal injustices and provide informed critical analysis begin to disappear, making it all the more difficult, if not dangerous, to hold dominant power accountable. Notions of virtue, honor, respect and compassion are policed, and those who advocate them are punished.

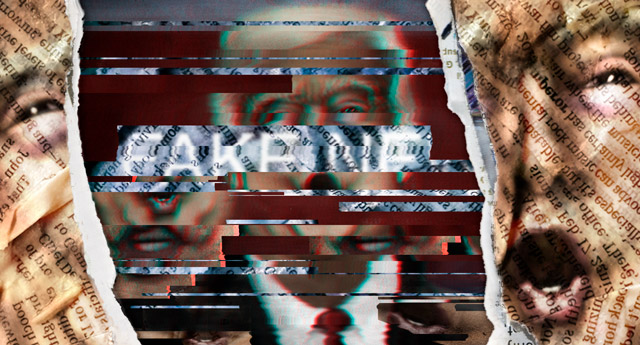

I think it is fair to argue that Orwell’s nightmare vision of the future is no longer fiction. Under the regime of Donald Trump, the Ministry of Truth has become the Ministry of «Fake News,» and the language of «Newspeak» has multiple platforms and has morphed into a giant disimagination machinery of propaganda, violence, bigotry, hatred and war.

With the advent of the Trump presidency, language is undergoing a shift in the United States: It now treats dissent, critical media and scientific evidence as a species of «fake news.» The administration also views the critical media as the «enemy of the American people.» In fact, Trump has repeated this view of the press so often that almost a third of Americans believe it and support government-imposed restrictions on the media, according to a Poynter survey. Language has become unmoored from critical reason, informed debate and the weight of scientific evidence, and is now being reconfigured within new relations of power tied to pageantry, political theater and a deep-seated anti-intellectualism, increasingly shaped by the widespread banality of celebrity culture, the celebration of ignorance over intelligence, a culture of rancid consumerism, and a corporate-controlled media that revels in commodification, spectacles of violence, the spirit of unchecked self-interest and a «survival of the fittest» ethos.

Under such circumstances, language has been emptied of substantive meaning and functions increasingly to lull large swaths of the American public into acquiescence, if not a willingness to accommodate and support a rancid «populism» and galloping authoritarianism. The language of civic literacy and democracy has given way to the language of saviors, decline, bigotry and hatred. One consequence is that matters of moral and political responsibility disappear, injustices proliferate and language functions as a tool of state repression. The Ministry of «Fake News» works incessantly to set limits on what is thinkable, claiming that reason, standards of evidence, consistency and logic no longer serve the truth, because the latter are crooked ideological devices used by enemies of the state. «Thought crimes» are now labeled as «fake news.»

The notion of truth is viewed by this president as a corrupt tool used by the critical media to question his dismissal of legal checks on his power — particularly his attacks on judges, courts, and any other governing institutions that will not promise him complete and unchecked loyalty. For Trump, intimidation takes the place of unquestioned loyalty when he does not get his way, revealing a view of the presidency that is more about winning than about governing. One consequence is myriad practices in which Trump gleefully humiliates and punishes his critics, willfully engages in shameful acts of self-promotion and unapologetically enriches his financial coffers.

David Axelrod, a former senior advisor to President Obama, is right in stating:

And while every president is irritated by the limitations of democracy on them, they all grudgingly accept it. [Trump] has not. He has waged a war on the institutions of democracy from the beginning, and I think in a very corrosive way.

New York Times writer Peter Baker adds to this charge by arguing that Trump — buoyed by an infatuation with absolute power and an admiration for authoritarians — uses language and the power of the presidency as a potent weapon in his attacks on the First Amendment, the courts and responsible governing. Trump’s admiration for a number of dictators is well known. What is often underplayed is his inclination to mimic their language and polices. For instance, Trump’s call for «law and order,» his encouraging police officers to be more violent with «thugs,» and his adoration of all things militaristic echoes the ideology and language of Philippine President and strongman Rodrigo Duterte, who has called for mass murder and boasted about «killing criminals with his own hand.»

Fascism starts with words. Trump’s use of language and his manipulative use of the media as political theater echo earlier periods of propaganda, censorship and repression.

At the same time, it would be irresponsible to suggest that the current expression of authoritarianism in US politics began with Trump, or that the context for his rise to power represents a distinctive moment in American history. As Howard Zinn points out in A People’s History of the United States, the US was born out of acts of genocide, nativism and the ongoing violence of white supremacy. Moreover, the US has a long history of demagogues, extending from Huey Long and Joe McCarthy to George Wallace and Newt Gingrich. Authoritarianism runs deep in American history, and Trump is simply the end point of these anti-democratic practices.

With the rise of casino capitalism, a «winner-take-all» ethos has made the United States a mean-spirited and iniquitous nation that has turned its back on the poor, underserved, and those considered racially and ethnically disposable. It is worth noting that in the last 40 years, we have witnessed an increasing dictatorship of finance capital and an increasing concentration of power and ownership regarding the rise and workings of the new media and mainstream cultural apparatuses. These powerful digital and traditional pedagogical apparatuses of the 21st century have turned people into consumers, and citizenship into a neoliberal obsession with self-interest and an empty notion of freedom. The ecosystem of visual and print representations has taken on an unprecedented influence, given the merging of power and culture as a dominant political and pedagogical force. This cultural apparatus has become so powerful, in fact, that it is difficult to dispute the central role it played in the election of Donald Trump to the presidency. Analyzing the forces behind the election of Trump, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt provide a cogent commentary on the political and pedagogical power of an old and updated media landscape. They write:

Undoubtedly, Trump’s celebrity status played a role. But equally important was the changed media landscape…. By one estimate, the Twitter accounts of MSNBC, CNN, CBS, and NBC — four outlets that no one could accuse of pro-Trump leanings — mentioned Trump twice as often as Hillary Clinton. According to another study, Trump enjoyed up to $2 billion in free media coverage during the primary season. Trump didn’t need traditional Republican power brokers. The gatekeepers of the invisible primary weren’t merely invisible; by 2016, they were gone entirely.

What is crucial to remember here, as Ruth Ben-Ghiat notes, is that fascism starts with words. Trump’s use of language and his manipulative use of the media as political theater echo earlier periods of propaganda, censorship and repression. Commenting on the Trump administration’s barring the Centers for Disease Control to use certain words, Ben-Ghiat writes:

The strongman knows that it starts with words…. That’s why those who study authoritarian regimes or have had the misfortune to live under one may find something deeply familiar about the Trump administration’s decision to bar officials at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) from using certain words («vulnerable,» «entitlement,» «diversity,» «transgender,» «fetus,» «evidence-based» and «science-based»). The administration’s refusal to give any rationale for the order, and the pressure it places on CDC employees, have a political meaning that transcends its specific content and context…. The decision as a whole links to a larger history of how language is used as a tool of state repression. Authoritarians have always used language policies to bring state power and their cults of personality to bear on everyday life. Such policies affect not merely what we can say and write at work and in public, but also [attempt] to change the way we think about ourselves and about others. The weaker our sentiments of solidarity and humanity become — or the stronger our impulse to compromise them under pressure — the easier it is for authoritarians to find partners to carry out their repressive policies.

Under fascist regimes, the language of brutality and culture of cruelty was normalized through the proliferation of the strident metaphors of war, battle, expulsion, racial purity and demonization. As German historians such as Richard J. Evans and Victor Klemperer have made clear, dictators such as Hitler did more than corrupt the language of a civilized society, they also banned words. Soon afterwards, they banned books and the critical intellectuals who wrote them. They then imprisoned those individuals who challenged Nazi ideology and the state’s systemic violations of civil rights. The endpoint was an all-embracing discourse of disposability, the emergence of concentration camps, and genocide fueled by a politics of racial purity and social cleansing. Echoes of the formative stages of such actions are with us once again. They provide just one of the historical signposts of an American-style neo-fascism that appears to be engulfing the United States, after simmering in the dark for years.

Under such circumstances, it is crucial to interrogate, as the first line of resistance, how this level of systemic linguistic derangement and corruption shapes everyday life. It is essential to start with language, because it is the first place tyrants begin to promote their ideologies, hatred, and systemic politics of disposability and erasure. Trump is not unlike many of the dictators he admires. What they all share as strongmen is the use of language in the service of violence and repression, as well as a fear of language as a symbol of identity, critique, solidarity and collective struggle. None of them believe that the truth is essential to a responsible mode of governance, and all of them support the notion that lying on the side of power is fundamental to the process of governing, however undemocratic such a political dynamic may be.

In a throwback to the language of fascism, he has repeatedly positioned himself as the only one who can save the masses.

Lying has a long legacy in American politics and is a hallmark of authoritarian regimes. Victor Klemperer in his classic book, The Language of the Third Reich, reminds us that Hitler had a «deep fear of the thinking man and [a] hatred of the intellect.» Trump is not only a serial liar, but he also displays a deep contempt for critical thinking and has boasted about how he loves the uneducated. Not only have mainstream sources such as The Washington Post and The New York Times published endless examples of Trump’s lies, they have noted that even in the aftermath of such exposure, he continues to be completely indifferent to being exposed as a serial liar.

In a 30-minute interview with The New York Times on December 28, 2017, The Washington Post reported that Trump made «false, misleading or dubious claims … at a rate of one every 75 seconds.» Trump’s language attempts to infantilize, seduce and depoliticize the public through a stream of tweets, interviews and public pronouncements that disregard facts and the truth. Trump’s more serious aim is to derail the architectural foundations of truth and evidence in order to construct a false reality and alternative political universe in which there are only competing fictions with the emotional appeal of shock theater.

More than any other president, he has normalized the notion that the meaning of words no longer matters, nor do traditional sources of facts and evidence. In doing so, he has undermined the relationship between engaged citizenship and the truth, and has relegated matters of debate and critical assessment to a spectacle of bombast, threats, intimidation and sheer fakery. This is the language of dictators, one that makes it difficult to name injustices, define politics as something more than rule by the powerful, and make and justify real equitable rules, shared relations of power, and a strong democratic politics.

But the language of fascism does more that normalize falsehoods and ignorance. It also promotes a larger culture of short-term attention spans, immediacy and sensationalism. At the same time, it makes fear and anxiety the normalized currency of exchange and communication. Masha Gessen is right in arguing that Trump’s lies are different than ordinary lies and are more like «power lies.» In this case, these are lies designed less «to convince the audience of something than to demonstrate the power of the speaker.» In short, Trump’s prodigious tweets are not just about the pathology of endless fabrications, they also function to reinforce a pedagogy of infantilism, designed to animate his base in a glut of shock while reinforcing a culture of war, fear, divisiveness and greed in ways that often disempower his critics.

Memories inconvenient to authoritarian rule are now demolished, so the future can be shaped so as to become indifferent to the crimes of the past.

How else to explain Trump’s desire to attract scorn from his critics and praise from his base through a never-ending production of tweets and electronic shocks reminiscent of the tantrums of a petulant 10-year-old? The examples just keep coming and appear to get more bizarre as time goes on. Peter Baker and Michael Tackett sum up a number of bizarre and reckless tweets that Trump produced to inaugurate the New Year. They write:

President Trump again raised the prospect of nuclear war with North Korea, boasting in strikingly playground terms on Tuesday night that he commands a «much bigger» and «more powerful» arsenal of devastating weapons than the outlier government in Asia. «Will someone from his depleted and food starved regime please inform [North Korean Leader Kim Jong Un] that I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his, and my Button works!» It came on a day when Mr. Trump, back in Washington from his Florida holiday break, effectively opened his new year with a barrage of provocative tweets on a host of issues. He called for an aide to Hillary Clinton to be thrown in jail, threatened to cut off aid to Pakistan and the Palestinians, assailed Democrats over immigration, claimed credit for the fact that no one died in a jet plane crash last year and announced that he would announce his own award next Monday for the most dishonest and corrupt news media.

Trump appropriates crassness as a weapon. In a throwback to the language of fascism, he has repeatedly positioned himself as the only one who can save the masses, reproducing the tired script of the savior model endemic to authoritarianism. In 2016 at the Republican National Convention, Trump stated without irony that he alone would save a nation in crisis, captured in his insistence that, «I am your voice, I alone can fix it. I will restore law and order.» Trump’s latter emphasis on restoring the authoritarian value of law and order has overtones of creating a new racial regime of governance, one that mimics what the historian Cedric J. Robinson once called the «rewhitening of America.» Such racially charged language points to the growing presence of a police state in the US and its endpoint in a fascist state where large segments of the population are rendered disposable, incarcerated or left to fend on their own in the midst of massive degrees of inequality. There is more at work here than an oversized, if not delusional ego. Trump’s authoritarianism is also fueled by braggadocio and misdirected rage. There is also a language that undermines the bonds of solidarity, abolishes institutions meant to protect the vulnerable, and a full-fledged assault on the environment.

Trump’s language does more than produce a litany of falsehoods, fears and poisonous attacks on those considered disposable; it works hard to prevent people from having an internal dialogue with themselves and others.

In addition, Trump’s ceaseless use of superlatives models a language that encloses itself in a circle of certainty while taking on religious overtones. Not only do such words pollute the space of credibility, they also wage war on historical memory, humility and the belief that alternative worlds are possible. For Trump and his followers, there is a recognizable threat to their power in the political and moral imperative to learn from a dark version of the past, so as to not repeat or update the dark authoritarianism of the 1930s. Trump is the master of manufactured illiteracy, and his public relations machine aggressively engages in a boundless theater of self-promotion and distractions — both of which are designed to whitewash any version of the past that might expose the close alignment between Trump’s language and policies and the dark elements of a fascist past.

Trump revels in an unchecked mode of self-congratulation bolstered by a limited vocabulary filled with words like «historic,» «best,» «the greatest,» «tremendous» and «beautiful.» As Wesley Pruden observes:

Nothing is ever merely «good,» or «fortunate.» No appointment is merely «outstanding.» Everything is «fantastic,» or «terrific,» and every man or woman he appoints to a government position, even if just two shades above mediocre, is «tremendous.» The Donald never met a superlative he didn’t like, himself as the ultimate superlative most of all.

Trump’s relentless exaggerations suggest more than hyperbole or the self-indulgent use of language. This is true even when he claims he «knows more about ISIS than the generals,» «knows more about renewables than any human being on Earth,» or that nobody knows the US system of government better than he does. There is also a resonance with the rhetoric of fascism. As the historian Richard J. Evans writes in The Third Reich in Power:

The German language became a language of superlatives, so that everything the regime did became the best and the greatest, its achievements unprecedented, unique, historic, and incomparable…. The language used about Hitler, Klemperer noted was shot through and through with religious metaphors; people ‘believed in him,’ he was the redeemer, the savior, the instrument of Providence, his spirit lived in and through the German nation….Nazi institutions domesticated themselves [through the use of a language] that became an unthinking part of everyday life.

Under the Trump regime, memories inconvenient to authoritarian rule are now demolished in the domesticated language of superlatives, so the future can be shaped so as to become indifferent to the crimes of the past. For instance, he has talked about the Civil War as if historians have not asked why it took place, while at the same time ignoring the role of slavery in its birth. During a Black History Month event, he talked about the great abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass as if he were still alive. Trump’s ignorance of the past finds its counterpart in his celebration of a history that has enshrined racism, tweeted neo-Nazi messages, and embraced the «blood and soil» of white supremacy.

How else to explain the legacy of white racism and fascism historically inscribed in his signature slogan «Make America Great Again» and his use of the anti-Semitic phrase «America First,» long associated with Nazi sympathizers during World War II? How else to explain his support for bringing white supremacists such as Steve Bannon (now resigned) and Jeff Sessions, both with a long history of racist comments and actions, into the highest levels of governmental power? Or his retweeting of an anti-Islamic video originally posted by Britain First, a far-right extremist group — an action that was condemned by British Prime Minister Theresa May?

It gets worse: Trump created a false equivalence between white supremacist neo-Nazi demonstrators and those who opposed them in Charlottesville, Virginia. In doing so, he argued that there were «very fine people on both sides,» as if fine people march with protesters carrying Nazi flags shouting, «We will not be replaced by Jews.» Trump appears to be unable to differentiate «between people who think like Nazis and people who try to stop them from spewing their hate.»

If fascism is to be defeated, there is a need to make education central to politics.

But there is more than ignorance at work in Trump’s lengthy history of racist comments. Trump’s sympathy for white nationalism and white supremacy offers a clear explanation for his unbroken use of racist language about Mexican immigrants, Muslims, Syrian refugees and Haitians. It also points to Trump’s use of language as part of a larger political and pedagogical project to «mobilize hatred,» legitimate the discourse of intimidation and encourage the American public «to unlearn feelings of care and empathy that lead us to help and feel solidarity with others,» as Ben-Ghiat writes.

Trump’s nativism and ignorance works in the United States because it not only caters to what the historian Brian Klass refers to as «the tens of millions of Americans who have authoritarian or fascist leanings,» it also enables what he calls Trump’s attempt at «mainstreaming fascism.» He writes:

Like other despots throughout history, Trump scapegoats minorities and demonizes politically unpopular groups. Trump is racist. He uses his own racism in the service of a divide-and-rule strategy, which is one way that unpopular leaders and dictators maintain power. If you aren’t delivering for the people and you’re not doing what you said you were going to do, then you need to blame somebody else. Trump has a lot of people to blame.

Trump’s language, especially his endorsement of torture and contempt for international norms, normalizes the unthinkable, and points to a return to a past that evokes what Ariel Dorfman has called «memories of terror … parades of hate and aggression by the Ku Klux Klan in the United States and Adolf Hitler’s Freikorps in Germany…. executions, torture, imprisonment, persecution, exile, and, yes, book burnings, too.» Dorfman sees in the Trump era echoes of policies carried out under the dictator Pinochet in Chile. He writes:

Indeed, many of the policies instituted and attitudes displayed in post-coup Chile would prove models for the Trump era: extreme nationalism, an absolute reverence for law and order, the savage deregulation of business and industry, callousness regarding worker safety, the opening of state lands to unfettered resource extraction and exploitation, the proliferation of charter schools, and the militarization of society. To all this must be added one more crucial trait: a raging anti-intellectualism and hatred of «elites» that, in the case of Chile in 1973, led to the burning of books like ours.

The language of fascism revels in forms of theater that mobilize fear, hatred and violence. Sasha Abramsky is on target in claiming that Trump’s words amount to more than empty slogans. Instead, his language comes «with consequences, and they legitimize bigotries and hatreds long harbored by many but, for the most part, kept under wraps by the broader society. They give the imprimatur of a major political party to criminal violence.» Surely, the increase in hate crimes during Trump’s first year of his presidency testifies to the truth of Abramsky’s argument.

The history of fascism teaches us that language operates in the service of violence, desperation, and troubling landscapes of hatred, and carries the potential for inhabiting the darkest moments of history. It erodes our humanity, and makes too many people numb and silent in the face of ideologies and practices that are hideous acts of ethical atrocity. By undermining the concepts of truth and credibility, fascist-oriented language disables the ideological and political vocabularies necessary for a diverse society to embrace shared hopes, responsibilities and democratic values.

There is no democracy without informed citizens and no justice without a language critical of injustice.

Trump’s language — like that of older fascist regimes — mutilates contemporary politics, empathy, and serious moral and political criticism, and makes it more difficult to criticize dominant relations of power. Trump’s language does more than produce a litany of falsehoods, fears and poisonous attacks on those considered disposable; it works hard to prevent people from having an internal dialogue with themselves and others, relegating self-reflection, critical thinking, and the ability to question and judge to a scorned practice.

Trump’s fascistic language also fuels the rhetoric of war, toxic masculinity, white supremacy, anti-intellectualism and racism. What was once an anxious discourse about what Harvey Kaye calls the «possible triumph in America of a fascist-tinged authoritarian regime over liberal democracy» is no longer a matter of speculation, but a reality.

Any resistance to the new stage of American authoritarianism has to begin by analyzing its language, the stories it fabricates, the policies it produces, and the cultural, economic and political institutions that make it possible. Questions have to be raised about how right-wing educational and cultural apparatuses function both politically and pedagogically to shape notions of identity, desire, values, and emotional investments in the discourses of casino capitalism, white supremacy and a culture of cruelty. Trump’s language both shapes and embodies policies that have powerful consequences on people’s lives, and such effects must be made visible, tallied up, and used to uncover oppressive forms of power that often hide in the shadows. Rather than treat Trump’s lies and fear-mongering as merely an expression of the thoughts of a petulant and dangerous demagogue, it is crucial to analyze their historical roots, the institutions that reproduce and legitimate them, the pundits who promote them, and the effects they have on the texture of everyday life.

Trump’s language is not his alone. It is the language of a nascent fascism that has been brewing in the US for some time. It is a language that is comfortable viewing the world as a combat zone, a world that exists to be plundered. It is a view of those deemed different as a threat to be feared, if not eliminated. Frank Rich is correct in insisting that Trump is the blunt instrument of a populist authoritarian movement whose aim is «the systemic erosion of political, ethical, and social norms» central to a substantive democracy. And Trump’s major weapon is a toxic language that functions as a form of «cultural vandalism» that promotes hate, embraces the machinery of the carceral state, makes white supremacy a central tenant of governance, and produces unthinkable degrees of inequality in wealth and power.

Trump’s language has a history that must be acknowledged, made known for the suffering it produces, and challenged with an alternative critical and hope-producing narrative. Such a language must be willing to make power visible, uncover the truth, contest falsehoods, and create a formative and critical culture that can nurture and sustain collective resistance to the diverse modes of oppression that characterize the times that have overtaken the United States, and increasingly many other countries. Progressives need a language that both embraces the political potential of diverse forms racial, gender and sexual identity, and the forms of «oppression, exclusion, and marginalization» they make visible while simultaneously working to unify such movements into a broader social formation and political party willing to challenge the core values and institutional structures of the American-style fascism. No form of oppression, however hideous, can be overlooked. And with that critical gaze must emerge a critical language, a new narrative and a different story about what a socialist democracy will look like in the United States.

At the same time, there is a need to strengthen and expand the reach and power of established public spheres as sites of critical learning. There is also a need to encourage artists, intellectuals, academics and other cultural workers to talk, educate, make oppression visible, and challenge the normalizing discourses of casino capitalism, white supremacy and fascism. There is no room here for a language shaped by political purity or a limited to politics of outrage. A truly democratic vision has a broader and more capacious overview and project of struggle and transformation.

Language is not simply an instrument of fear, violence and intimidation; it is also a vehicle for critique, civic courage, resistance, and engaged and informed agency. We live at a time when the language of democracy has been pillaged, stripped of its promises and hopes. If fascism is to be defeated, there is a need to make education central to politics. In part this can be done with a language that exposes and unravels falsehoods, systems of oppression and corrupt relations of power while making clear that an alternative future is possible. A critical language can guide us in our thinking about the relationship between older elements of fascism and how such practices are emerging in new forms. The search and use of such a language can also reinforce and accelerate the need for young people to continue creating alternative public spaces in which critical dialogue, exchange and a new understanding of politics in its totality can emerge. Focusing on language as a strategic element of political struggle is not only about meaning, critique and the search for the truth, it is also about power, both in terms of understanding how it works and using it as part of ongoing struggles that merge the language of critique and possibility, theory and action.

Without a faith in intelligence, critical education and the power to resist, humanity will be powerless to challenge the threat that fascism and right-wing populism pose to the world. All forms of fascism aim at destroying standards of truth, empathy, informed reason and the institutions that make them possible. The current struggle against a nascent fascism in the United States is not only a struggle over economic structures or the commanding heights of corporate power. It is also a struggle over visions, ideas, consciousness and the power to shift the culture itself.

Progressives need to formulate a new language, alternative cultural spheres and fresh narratives about freedom, the power of collective struggle, empathy, solidarity and the promise of a real socialist democracy. We need a new vision that refuses to equate capitalism and democracy, normalize greed and excessive competition, and accept self-interest as the highest form of motivation. We need a language, vision and understanding of power to enable the conditions in which education is linked to social change and the capacity to promote human agency through the registers of cooperation, compassion, care, love, equality and a respect for difference.

Any struggle for a radical democratic socialist order will not take place if «the lessons from our dark past [cannot] be learned and transformed into constructive resolutions» and solutions for struggling for and creating a post-capitalist society. Ariel Dorfman’s ode to the struggle over language and its relationship to the power of the imagination, collective resistance and hope offers a fitting reminder of what needs to be done. He writes:

We must trust that the intelligence that has allowed humanity to stave off death, make medical and engineering breakthroughs, reach the stars, build wondrous temples, and write complex tales will save us again. We must nurse the conviction that we can use the gentle graces of science and reason to prove that the truth cannot be vanquished so easily. To those who would repudiate intelligence, we must say: you will not conquer and we will find a way to convince.

In the end, there is no democracy without informed citizens and no justice without a language critical of injustice.

Source:

http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/43159-challenging-trumps-language-of-fascism

Users Today : 10

Users Today : 10 Total Users : 35459476

Total Users : 35459476 Views Today : 13

Views Today : 13 Total views : 3417771

Total views : 3417771