United States / 26-08-2018 / Author: Katrina Schwartz / Source: KQED

Amidst the discussions about content standards, curriculum and teaching strategies, it’s easy to lose sight of the big goals behind education, like giving students tools to deepen their quantitative and qualitative understanding of the world. Teaching for understanding has always been a challenge, which is why Harvard’s Project Zero has been trying to figure out how great teachers do it.

Some teachers discuss metacognition with students, but they often simplify the concept by describing only one of its parts — thinking about thinking. Teachers are trying to get students to slow down and take note of how and why they are thinking and to see thinking as an action they are taking. But two other core components of metacognition often get left out of these discussions — monitoring thinking and directing thinking. When a student is reading and stops to realize he’s not really understanding the meaning behind the words, that’s monitoring. And most powerfully, directing thinking happens when students can call upon specific thinking strategies to redirect or challenge their own thinking.

“When we have a rich meta-strategic base for our thinking, that helps us to be more independent learners,” said Project Zero senior research associate Ron Ritchhart at a Learning and the Brain conference. “If we don’t have those strategies, if we aren’t aware of them, then we’re waiting for someone else to direct our thinking.”

Helping students to “learn how to learn” or in Ritchhart’s terminology, become “meta-strategic thinkers” is crucial for understanding and becoming a life-long learner. To discover how aware students are of their thinking at different ages, Ritchhart has been working with schools to build “cultures of thinking.” His theory is that if educators can make thinking more visible, and help students develop routines around thinking, then their thinking about everything will deepen.

His research shows that when fourth graders are asked to develop a concept map about thinking, most of their brainstorming centers around what they think and where they think it. “When students don’t have strategies about thinking, that’s how they respond – what they think and where they think,” Richhart said. Many fifth graders start to include broad categories of thinking on their concept maps like “problem solving” or “understanding.” Those things are associated with thinking, but fifth graders often haven’t quite hit on the process of thinking.

By sixth grade a few students are starting to include some strategies for thinking in their maps, such as “concentrate” or “don’t get caught up in things that aren’t relevant.” But by ninth grade many students include specific strategies for thinking on their concept maps, including “making connections,” “comparing” and “breaking things down.”

Ritchhart studied 400 students at a school focusing on cultivating a culture of thinking. The study had no control group, but Ritchhart could chart development of metacognition from 4th-11th grades.

“Students basically made a two-and-a-half year gain from what would be expected just from teachers trying to create that culture of thinking,” Ritchhart said. He admits that the study isn’t definitive, but to him it’s proof that when teachers focus on these ideas they do see improvement.

HOW CAN EDUCATORS HELP?

In a culture of thinking, students recognize that collective and individual thinking is valued, visible and actively promoted as part of the regular day-to-day experience of all group members. This type of culture can exist in any place where learning is part of the experience including school, after school programming or museum programs.

To help make these ideas more concrete, Ritchhart and his colleagues have been working to hone in on a short list of “thinking moves” related to understanding. To test whether these moves were really crucial, researchers asked themselves: could a student say she really understood something if she hadn’t engaged in these activities? They believe the important “thinking moves” that lead to understanding are:

- Naming: being able to identify the parts and pieces of a thing

- Inquiry: questioning should drive the process throughout

- Looking at different perspectives and viewpoints

- Reasoning with evidence

- Making connections to prior knowledge, across subject areas, even into personal lives

- Uncovering complexity

- Capture the heart and make firm conclusions

- Building explanations, interpretations and theories.

These thinking moves all point to the conclusion that learning doesn’t happen through the mere delivery of information. “Learning only occurs when the learner does something with that information,” Ritchhart said. “So as teachers we need to think not only about how we will deliver that content, but also what we will have students do with that content.”

One easy way to start asking students to be more metacognitive is to build in reflection time about thinking. Ask students to think about the lesson and identify the kinds of thinking they used throughout. That not only builds vocabulary around thinking, but it often gives kids confidence to name specific thinking strategies they used. Taking this time to reflect also reminds students that they did real work during the lesson.

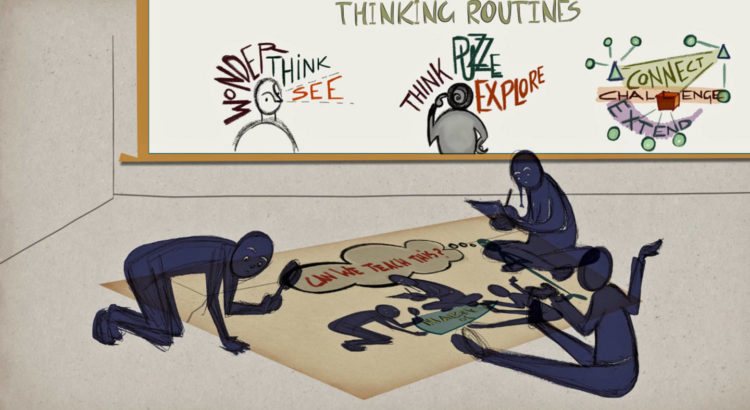

THINKING ROUTINES

To get at how teachers make thinking visible, Ritchhart studied teachers who were very effective at helping student dive below surface level retention of information into really understanding material as it connects to the rest of their studies and their lives. He noticed none of them taught a lesson on thinking.

“They had routines and structures that scaffolded and supported student thinking,” Ritchhart said. This discovery led him and colleagues at Project Zero to develop “thinking routines” that all teachers can use to help students develop the habits of mind that lead to more understanding.

One way to develop a culture of thinking is to pick one of the thinking routines Project Zero has designed and use it over and over in a variety of contexts. Rather than trying each routine once, applying one routine in multiple ways will help make thinking in that way habitual. It becomes almost an expectation in a classroom, like other class norms.

One example of this that goes beyond the K-12 classroom comes from Harvard Medical School, where instructors were struggling to train students to listen to patients and make strong diagnoses based on the symptoms they heard. As an experiment, the medical school offered an elective module to students, where once a week they would join a fine arts class using the “See, Think, Wonder” thinking routine to observe art. After 10 weeks, all the medical students were assessed on clinical diagnosing and the students who had done “See, Think, Wonder” had improved much more than those who had not participated.

“One of the reasons we call them thinking routines is that through their use it is the thinking that becomes routine,” Ritchhart said. Project Zero is working with teachers around the country to apply thinking routines in the classroom and many have reported that after doing the routines in a structured way several times students naturally start using the protocols for everything.

Source of Article:

https://www.kqed.org/mindshift/44227/when-kids-have-structure-for-thinking-better-learning-emerges

ove/mahv

Users Today : 21

Users Today : 21 Total Users : 35460152

Total Users : 35460152 Views Today : 35

Views Today : 35 Total views : 3418818

Total views : 3418818