By: Henry A. Giroux

Under the reign of Donald Trump, politics has become an extension of war and death has become a permanent attribute of everyday life. Witness the US’s plunge into a dystopian world that bears the menacing markings of what presents itself as an endless series of isolated catastrophes. All of these are inevitably treated as unrelated incidents; victims subject to the toxic blows of fate. Mass misery and mass violence that result from the refusal of a government to address such pervasive and permanent crises are now reinforced by the popular neoliberal assumption that people are completely on their own, solely responsible for the ill fortune they experience. This ideological assumption is reinforced by undermining any critical attention to the conditions produced by stepped-up systemic state violence, or the harsh consequences of a capricious and cruel head of state.

«Progress» and dystopia have become synonymous, just as state-endorsed social provisions and government responsibility are exiled by the neoliberal authorization of freedom as the unbridled promotion of self-interest: a narrow celebration of limitless «choice,» and an emphasis on individual responsibility that ignores broader systemic structures and socially produced problems. Existential security no longer rests on collective foundations, but on privatized solutions and facile appeals to moral character.

Under Trump, a politics of disposability has merged with an ascendant authoritarianism in the United States in which the government’s response to such disparate issues as the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) crisis, the devastation of Puerto Rico by Hurricane Maria and the mass shooting in Las Vegas are met uniformly with state-sanctioned and state-promoted violence.

In an age when market values render democratic values moot, a war culture drives disposability politics. Indeed, the politics of disposability has a long legacy in the United States, and extends from the genocide of Native Americans and slavery, to the increasing criminalization of everyday behaviors and the creation of a mass incarceration state.

In the 1970s, the politics of disposability, guided by the growing financialization of a neoliberal economy, manifested itself primarily in the form of legislation that undermined the welfare state, social provisions and public goods, while expanding the carceral state. This was part of the soft war waged against democracy — mostly hidden and wrapped in the discourse of austerity, «law and order» and market-based freedoms.

At the beginning of the 21st century, we have seen the emergence of a new kind of politics of death, the effects of which extend from the racist response to Hurricane Katrina to the lead poisoning of thousands of children in Flint, Michigan, and dozens of other cities. This is a politics in which entire populations are considered disposable, an unnecessary burden on state coffers, and consigned to fend for themselves. This is a politics that now merges with aggressive and violent efforts to silence dissent, analysis and the very conditions of critical thought. People who are Black, Brown, poor, disabled or otherwise marginalized are now excluded from the rights and guarantees accorded to fully fledged citizens of the republic, removed from the syntax of suffering, and left to fend for themselves in the face of natural or human-made disasters. And their efforts to mobilize have been met with murderous police crackdowns and deportations.

With the election of Trump, the politics of disposability and the war against democracy have taken on a much harder and crueler edge, with the president urging the police to «take the gloves off» and the attorney general calling for a regressive «law and order» campaign steeped in racism.

Under 21st century neoliberal capitalism, and especially under the Trump regime, there has been an acceleration of the mechanisms by which vulnerable populations are rendered unknowable, undesirable, unthinkable, considered an excess cost and stripped of their humanity. Relegated to zones of social abandonment and political exclusion, targeted populations become incomprehensible, civil rights disappear, hardship and suffering are normalized, and human lives are targeted and negated by diverse machineries of violence as dangerous, pathological and redundant. For those populations rendered disposable, ethical questions go unasked as the mechanisms of dispossession, forced homelessness and forms of social death feed corrupt political systems and forms of corporate power removed from any sense of civic and social responsibility. In many ways, the Trump administration is the new face of a politics of disposability that thrives on the energies of the vulnerable and powerless. Under such conditions, power is defined by the degree to which it is abstracted from any sense of responsibility or critical analysis.

This type of disposability is especially visible under Trump, not only because of his discourse of humiliation, bigotry and objectification, but also in his policies, which are blatantly designed to punish those populations who are the most vulnerable. These include the victims in Puerto Rico of Hurricane Maria, immigrant children no longer protected by DACA, and a push to expand the armed forces and the para-militarization of local police forces throughout the country as part of a race-based «law and order» policy. Trump is the endpoint of a new dystopian model of disposability, and has become a window on the growing embrace of violence and white supremacy at the highest levels of power, as both a practice and ideological legitimation for increasing a culture of fear. Fear, in this context, is framed mostly within a discourse of threats to personal safety, serving to increase the criminalization of a wide range of everyday behaviors while buttressing the current administration’s racist call for «law and order.» This culture of fear threatens to make more and more individuals and groups inconsequential and expendable.

Under such circumstances, the US’s dystopian impulses not only produce harsh and dire political changes, but also a failure to address a continuous series of economic, ecological and social crises. At the same time, the machinery of disposability and death rolls on, conferring upon entire populations the status of the living dead. The death-dealing logic of disposability has been updated and now parades in the name of freedom, choice, efficiency, security, progress and, ironically, democracy. Disposability has become so normalized that it is difficult to recognize it as a distinctive if not overriding organizing principle of the new American authoritarianism.

While the politics of disposability has a long legacy in the United States, Trump has given it a new and powerful impetus. This era differs from the recent past both in terms of its unapologetic embrace of the ideology of white supremacy and its willingness to expand state-sanctioned violence and death as part of a wider project of the US’s descent into authoritarianism.

Running through these events is a governmental response that has abandoned a social contract designed, however tepidly, to prevent hardship, suffering and death. Large groups of people have been catapulted out of the range of human beings for whom the government has limited, if any, responsibility. Such populations, inclusive of such disparate groups as the residents of Puerto Rico and the Dreamers, are left to fend for themselves in the face of disasters. They are treated as collateral damage in the construction of a neoliberal order in which those marginalized by race and class become the objects of a violent form of social engineering relegating its victims to what Richard Sennett has termed a «specter of uselessness,» whose outcomes are both tragic and devastating.

A politics of disposability provides a theoretical and political narrative that connects the crisis produced in Puerto Rico after the devastating effects of Hurricane Maria to the crisis surrounding Trump’s revoking of the DACA program. Trump’s support of state-sanctioned violence normalizes a culture and spectacle of violence, one not unrelated to the mass shooting that took place in Las Vegas.

First, let’s examine the crisis in Puerto Rico as a systemic example of both state violence and a politics of disposability and social abandonment.

Puerto Rico as a Zone of Abandonment

On September 20, 2017, Hurricane Maria, a Category 5 storm, slammed into and devastated the island of Puerto Rico. In the aftermath of a slow government response to the massive destruction, conditions in Puerto Rico have reached unprecedented and unacceptable levels of misery, hardship and suffering. As of October 19, over 1 million people were without drinking water, 80 percent of the island lacked electricity, and ongoing reports by medical staff and other respondents indicate that more and more people were dying. Thousands of people are living in shelters, lack phone service, and have to bear the burden of a health care system in shambles.

Such social immiseration is complicated by the fact that the island is home to 21 hazardous superfund sites, which pose deadly risks to human health and the environment. Lois Marie Gibbs ominously reports that waterborne illnesses are spreading, just as hospitals are running low on medicines. Caitlin Dickerson observed that the «the Environmental Protection Agency cited reports of residents trying to obtain drinking water from wells at hazardous Superfund sites.» These are wells that were once sealed to avoid exposure to deadly toxins. The governor of Puerto Rico, Ricardo Rossello, warned that a number of people have died from Leptospirosis, a bacterial disease spread by animal urine.

The Trump administration’s response has been unforgivably slow, with conditions worsening. Given the accelerating crisis, the mayor of San Juan, Carmen Yulín Cruz, made a direct appeal to President Trump for aid, stating with an acute sense of urgency, «We are dying.» Trump responded by lashing out at her personally by telling her to stop complaining. Cruz became emotional when referring to elderly and ill victims of Maria that she could not reach and who were «still at great risk in places where relief supplies and medical help had yet to arrive.» Cruz said the situation for many of these people was «like a slow death.» Stories began to emerge in the press that validated Cruz’s concerns. Many seriously ill dialysis patients either had their much-needed treatments reduced or could not get access to health care facilities. Because of the lack of electricity, Harry Figueroa, a teacher, «went a week without the oxygen that helped him breathe» and eventually died at 58. «His body went unrefrigerated for so long that the funeral director could not embalm his badly decomposed corpse.»

Scholar Lauren Berlant has used the term «slow death» in her own work to refer «to the physical wearing out of a population and the deterioration of people in that population that is very nearly a defining condition of their experience and historical existence.» Slow death captures the colonial backdrop of global regimes of ideological and structural oppression deeply etched in Puerto Rico’s history. The scale of suffering and devastation was so great that Robert P. Kadlec, the assistant secretary of Health and Human Services for preparedness and response stated that «The devastation I saw, I thought was equivalent to a nuclear detonation.»

Puerto Rico’s tragic and ruinous problems brought on by Hurricane Maria are amplified both by its $74 billion debt burden, an ongoing economic crisis, and the legacy of its colonial status and lack of political power in fighting for its sovereign and economic rights in Washington. With no federal representation and lacking the power to vote in presidential elections, it is difficult for Puerto Ricans to get their voices heard, secure the same rights as US citizens and put pressure on the Trump administration to address many of its longstanding problems. The latter include a poverty rate of 46 percent, a household median income of $19,350 [compared to the US median of $55,775], and a crippling debt. In fact, the debt burden is so overwhelming that «pre-Maria Puerto Rico was spending more on debt service than on education, health, or security. Results included the shuttering of 150 schools, the gutting of health care, increased taxes, splitting of families between the island and the mainland, and increased food insecurity.» Amy Davidson Sorkin was right in arguing that «Indeed, the crisis in Puerto Rico is a case study of what happens when people with little political capital need the help of their government.»

Not only did Trump allow three weeks to lapse before asking Congress to provide financial aid to the island, but his request reeked of heartless indifference to Puerto Rico’s economic hardships. Instead of asking for grants, he asked for loans. Throughout the crisis, Trump released a series of tweets in which he suggested that the plight of the Puerto Rican people was their own fault, lambasted local officials for supposedly not doing enough, and threatened to cut off aid from government services. Adding insult to injury, he also said that they were «throwing the government’s budget out of whack because we’ve spent a lot of money on Puerto Rico.»

Trump also suggested that the crisis in Puerto Rico was not a real crisis when compared to Hurricane Katrina. Trump’s view of Puerto Ricans as second-class citizens was exposed repeatedly in an ongoing string of tweets and comments that extended from the insulting notion that «they want everything to be done for them» to the visual image of Trump throwing paper towel rolls into a crowd as if he were on a public relations tour. Throughout the crisis, Trump has repeatedly congratulated himself on the government response to Puerto Rico, falsely stating that everybody thinks we are doing «an amazing job.» A month after the crisis, Trump insisted, without irony or a shred of self-reflection, that he would give himself a «perfect ten.»

These responses suggest more than a callous expression of self-delusion and indifference to the suffering of others. Trump’s callous misrecognition of the magnitude of the crisis in Puerto Rico and extent of the island’s misery and suffering, coupled with his insults and demeaning tweets, demonstrate the perpetuation of race and class oppressions through his governance. There is more at work here than a disconnection from the poor; there is also a white supremacist ideology that registers race as a central part of both Trump’s politics and a wider politics of disposability. It is difficult to miss the racist logic of reckless disregard for the safety and lives of Puerto Rican citizens, bordering on criminal negligence, which simmers just beneath the surface of Trump’s rhetoric and actions. Hurricane Maria exposed a long history of racism that confirms the structural abandonment of those who are poor, sick, elderly — and Black or Brown.

Trump embodies the commitments of a neoliberal authoritarian government that not only fails to protect its citizens, but reveals without apology the full spectrum of mechanisms to expand poverty, racism and hierarchies of class, making some lives disposable, redundant and excessive while others appear privileged and secure. Trump’s utterly failed response to the disaster in Puerto Rico reinforces Ta-Nehisi Coates’s claim that the spectacle of bigotry that shapes Trump’s presidency has «moved racism from the euphemistic and plausibly deniable to the overt and freely claimed.» What has happened in Puerto Rico also reveals the frightening marker of a politics of disposability in which any appeal to democracy loses its claim and becomes hard to imagine, let alone enact without the threat of violent retaliation.

Revoking DACA and the Killing of the Dream

Trump’s penchant for cruelty in the face of great hardship and human suffering is also strikingly visible in the racial bigotry that has shaped his cancellation of the DACA program, instituted in 2012 by President Obama. Under the program, over 800,000 undocumented immigrants brought to the country as children or teens before 2007 were allowed to live, study and work in the United States without fear of deportation. The program permitted these young people, known as Dreamers, to have access to Social Security cards, drivers’ licenses, and to advance their education, start small businesses and to be fully integrated into the fabric of American society. Seventy-six percent of Americans believe that Dreamers should be granted resident status or citizenship. In revoking the program, Trump has made clear his willingness to deport individuals who came to the US as children and who know the United States as their only home.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions was called upon to be the front man in announcing the cancellation of DACA. In barely concealed racist tones, Sessions argued that DACA had to end because «The effect of this unilateral executive amnesty, among other things, contributed to a surge of unaccompanied minors on the southern border that yielded terrible humanitarian consequences … denied jobs to hundreds of thousands of Americans by allowing those same jobs to go to illegal aliens» and had to be rescinded because «failure to enforce the laws in the past has put our nation at risk of crime, violence and even terrorism.» None of these charges is true.

Rather than taking jobs from American workers, Dreamers add an enormous benefit to the economy and «it is estimated that the loss of the Dreamers’ output will reduce the GDP by several hundred billion dollars over a decade.» Sessions’s claim that DACA contributed to a surge of unaccompanied minors at the border is an outright lie, given that the surge began in 2008, four years before DACA was announced, and it was largely due, as Mark Joseph Stern points out, «to escalating gang violence in Central America, as well as drug cartels’ willingness to target and recruit children in Mexico … [A] study published in International Migration … found that DACA was not one of these factors.»

Trump’s rescinding of DACA is politically indefensible and heartless. Only 12 percent of Americans want the Dreamers deported and this support is drawn mostly from Trump’s base of ideological extremists, religious conservatives and far-right nationalists. This would include former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon, who left the White House and now heads, once again, Breitbart, the right-wing news outlet. Bannon is a leading figure of the right-wing extremists influencing Trump and is largely responsible for bringing white supremacist and ultranationalist ideology from the fringes of society to the center of power. On a recent segment of the TV series «60 Minutes,» Bannon told Charlie Rose that the DACA program shouldn’t be codified, adding «As the work permits run out, they self deport…. There’s no path to citizenship, no path to a green card and no amnesty. Amnesty is non-negotiable.» Bannon’s comments are cruel but predictable given his support for the uniformly bigoted policies Trump has pushed before and after his election.

The call to end DACA is part of a broader racist anti-immigration agenda aimed at making America white again. The current backlash against people of color, immigrant youth and those others marked by the registers of race and class are not only heartless and cruel, they also invoke a throwback to the days of state-sponsored lynching and the imposed terror of the Ku Klux Klan. Additionally, they offer up an eerie resonance to the violent and repressive racist policies of the totalitarian governments that emerged in Germany in the 1930s and Latin America in the 1970s.

Las Vegas and the Politics of Violence

On October 1, 2017, Stephen Paddock, ensconced on the 32nd floor of the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino Hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada, opened fire on a crowd of country and western concertgoers below, killing 58 and wounding over 500. While the venues for such shootings differ, the results are always predictable. People die or are wounded, and the corporate media and politicians weigh in on the cause of the violence. If the assailant is a person of color or a Muslim, they are labeled a «terrorist,» but if they are white, they are often labeled as «mentally disturbed.» Paddock was immediately branded by President Trump as a «sick» and «deranged man» who had committed an act of «radical evil.»

Trump’s characterizing of the shooting as an act of radical evil is more mystifying than assuring, and it did little to explain how such an egregious act of brutality fits into a broader pattern of civic decline, cultural decay, political corruption and systemic violence. It also erases the role of state-sanctioned violence in perpetuating individual acts of brutality. Corporate media trade in isolated spectacles, and generally fail to connect these dots. Rarely is there a connection made in the mainstream media, for instance, between the fact that the US is the largest arms manufacturer with the biggest military budget in the world and the almost unimaginable fact that there are more than 300 million people who own guns in the United States, which amounts to «112 guns per 100 people.» While the Trump administration is not directly responsible for the bloodbath in Las Vegas, it does feed a culture of violence in the United States.

Many Republicans, including Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, reinforced the lack of civic and ethical courage that emerged in the aftermath of the Las Vegas massacre by arguing that it was «particularly inappropriate» to talk about gun reform or politics in general after a mass shooting. By eliminating the issue of politics from the discussion, figures like McConnell erased some basic realities, such as the power of gun manufacturers to flood the country with guns, and the power of lobbyists to ensure that gun-safety measures do not become part of a wider national conversation. This depoliticizing logic also enabled any discussion about Paddock to be centered on his actions as an aberration, as opposed to a manifestation of forces in the larger culture.

The corporate press, with few exceptions, was unwilling to address how and why mass shootings have become routine in the United States and how everyday violence benefits a broader industry of death that gets rich through profits made by the defense industry, the arms manufacturers and corrupt gun lobbyists. There was no reference to how young children are groomed for violence by educational programs sponsored by the gun industries, how video games and other aspects of a militarized culture are used to teach youth to be insensitive to the horrors of real-life violence, how the military-industrial complex «makes a living from killing through defense contracts, weapons manufacturing and endless wars.» Nor did much of the media address how war propaganda provided by the Pentagon influences not only pro-sports events and Hollywood blockbuster movies, but also reality TV shows, such as «American Idol» and «The X-Factor.»

In the aftermath of mass shootings, the hidden structures of violence disappear in the discourses of personal sorrow, the call for prayers and the insipid argument that such events should not be subject to political analysis. Trump’s dismissive comments on the Vegas shooting as an act of radical evil misses the fact that what is evil is the pervasive presence of violence throughout American history and the current emergence of extreme violence and mass shootings on college campuses, in elementary schools, at concerts and in diverse workplaces. Mass shootings may have become routine in the US, but the larger issue to be addressed is that violence is central to how the American experience is lived daily.

Militant Neoliberalism in an Armed USA

Militarized responses have become the primary medium for addressing all social problems, rendering critical thought less and less probable, less and less relevant. The lethal mix of anti-intellectualism, ideological fundamentalism and retreat from the ethical imagination that has grown stronger under Trump provides the perfect storm for what can be labeled a war culture, one that trades democratic values for a machinery of social abandonment, misery and death.

War as an extension of politics fuels a spectacle of violence that has overtaken popular culture while normalizing concrete acts of gun violence that kill 93 Americans every day. Traumatic events such as the termination of DACA or the refusal on the part of the government to quickly and effectively respond to the hardships experienced by the people of Puerto Rico no longer appear to represent an ethical dilemma to those in power. Instead, they represent the natural consequences of rendering whole populations disposable.

What is distinctive about the politics of disposability — especially when coupled with the transformation of governance into a wholesale legitimation of violence and cruelty under Trump — is that it has both expanded a culture of extreme violence and has become a defining feature of American life. The state increasingly chooses violence as a primary mode of engagement. Such choices imprison people rather than educate them, and legitimate the militarizing of every major public institutions from schools to airports. The carceral state now provides the template for interacting with others in a society governed by persistent rituals of violence.

Democracy is becoming all the more irrelevant in the United States under the Trump administration, especially in light of what Robert Weissman, the president of the watchdog group Public Citizen, calls «a total corporate takeover of the US government on a scale we have never seen in American history.» Corporate governance and economic sovereignty have reached new heights, just as illiberal democracy has become a populist flashpoint in reconfiguring much of Europe and normalizing the rise of populist bigotry and state-sanctioned violence aimed at immigrants and refugees fleeing from war and poverty. Democratic values and civic culture are under attack by a class of political extremists who embrace without reservation the cynical instrumental reason of the market, while producing on a global level widespread mayhem, suffering and violence. How else to explain the fact that over 70 percent of Trump’s picks for top administration jobs have corporate ties or work for major corporations? Almost all of these people represent interests diametrically opposed to the agencies for whom they now lead and are against almost any notion of the public good.

Hence, under the Trump regime, we have witnessed a slew of rollbacks and deregulations that will result in an increase in pollution, endangering children, the elderly and others who might be exposed to hazardous toxins. The New York Times has reported that one EPA appointee, Nancy Beck, a former executive at the American Chemistry Council, has initiated changes to make it more difficult to track and regulate the chemical perflourooctanoic acid, which has been linked to «kidney cancer, birth defects, immune system disorders and other serious health problems.»

The sense of collective belonging that underpins the civic vigor of a democracy is being replaced by a lethal survival-of-the-fittest ethos, and a desperate need to promote the narrow interests of capital and racist exclusion, regardless of the cost. At the heart of this collective ethos is a war culture stoked by fear and anxiety, one that feeds on dehumanization, condemns the so-called «losers,» and revels in violence as a source of pleasure and retribution. The link between violence and authoritarianism increasingly finds expression not only in endless government and populist assaults on vulnerable groups, but also in a popular culture that turns representations of extreme violence into entertainment.

The US has become a society organized both for the production of violence and the creation of a culture brimming with fear, paranoia and a social atomization. Under such circumstances, the murderous aggression associated with authoritarian states becomes more common in the United States and is mirrored in the everyday actions of citizens. If the government’s responses to crises that enveloped DACA and Puerto Rico point to a culture of state-sanctioned violence and cruelty, the mass shooting in Las Vegas represents the endpoint of a culture newly aligned with the rise of authoritarianism. The shooting in Las Vegas does more than point to a record-setting death toll for vigilante violence; it also provides a signpost about a terrifying new political and cultural horizon in the relationship between violence and everyday life. All of these incidents must be understood as a surface manifestation of a much larger set of issues endemic to the rise of authoritarianism in the United States.

These three indices of violence offer pointed and alarming examples of how inequality, systemic exclusion and a culture of cruelty define American society, even, and especially, as they destroy it. Each offers a snapshot of how war culture and violence merge. As part of a broader category indicting the rise of authoritarianism in the United States, they make visible the pervasiveness of violence as an organizing principle of American life. While it is easy to condemn the violence at work in each of these specific examples, it is crucial to address the larger economic, political and structural forces that create these conditions.

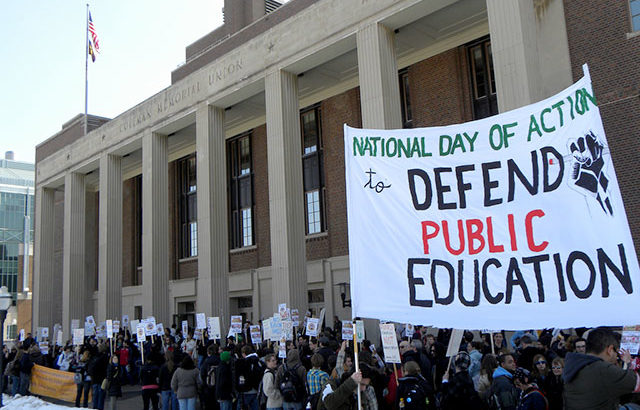

There is an urgent need for a broader awareness of the scope, range and effects of violence in the US, as well as the relationship between politics and disposability. Only then will the US be able to address the need for a radical restructuring of its politics, economics and institutions. Violence in the US has to be understood as part of a crisis of a politics and culture defined by meaninglessness, helplessness, neglect and disposability. Resistance to such violence, then, should produce widespread thoughtful, informed and collective action over the fate of democracy itself. This suggests the need for a shared vision of economic, racial and gender justice — one that offers the promise of a new understanding of politics and the need for creating a powerful coalition among existing social movements, youth groups, workers, intellectuals, teachers and other progressives. This is especially true under the Trump administration, since politics and democracy are now defined by a threshold of dysfunction that points not only to their demise, but to the ascendancy of American-style authoritarianism.

Source:

http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/42450-disposability-in-the-age-of-disasters-from-dreamers-and-puerto-rico-to-violence-in-las-vegas

Users Today : 39

Users Today : 39 Total Users : 35460056

Total Users : 35460056 Views Today : 54

Views Today : 54 Total views : 3418685

Total views : 3418685