GEM REPORT

The world was caught by surprise with the global pandemic emergency. But was it entirely unexpected? Pandemics have always been a likelihood. A pandemic has occurred every 10-50 years for the past centuries. In any given year, a 1% probability exists of an influenza pandemic that causes nearly 6 million pneumonia and influenza deaths or more globally. This translates into a 25% likelihood of such a pandemic over 30 years, and that’s just influenza.

It’s not ‘if’ a pandemic occurs, therefore, but ‘when’. ‘In order to mitigate human and financial losses as a result of future global pandemics, we must plan now’ was the call of experts in 2016 in the immediate aftermath of the Ebola virus epidemic in western Africa and the international organizations’ admission of the response having been slow. In this latest major and unfolding crisis, the emphasis has been on different health systems’ responses. But could education systems have been better prepared?

Pandemics needs to be factored into education planning, as much as in other sectors. Closing schools during disease outbreaks should not be taken lightly. As the 2020 GEM Report will tell us, schools are often the location not just for education but also for school meals or health interventions. But, according to the World Health Organisation, ‘under ideal conditions, school closure can reduce the demand for health care by an estimated 30-50% at the peak of the pandemic’. Clearly, then, with the risk of a pandemic striking, education planners need to be prepared for a stint of interrupted education.

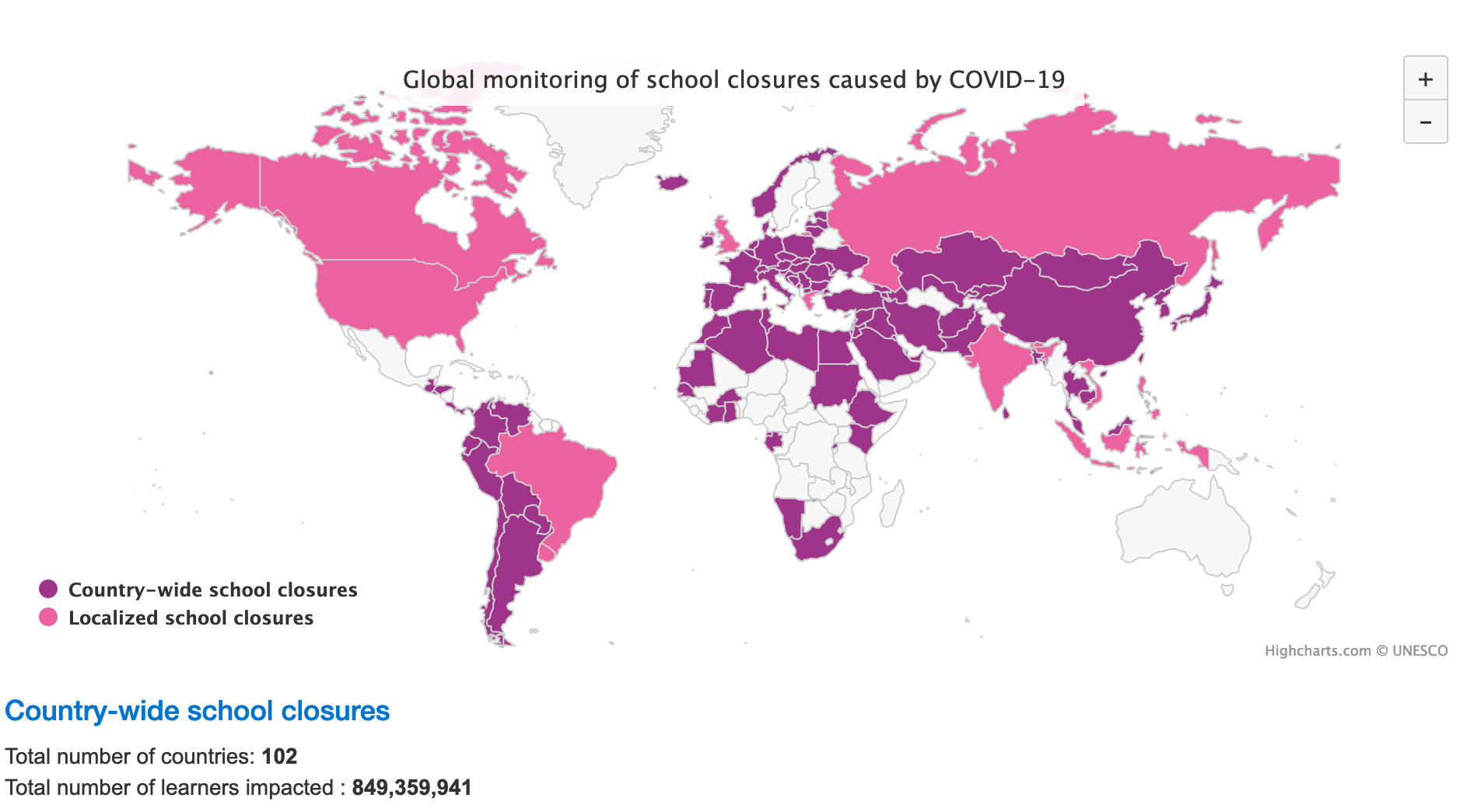

Faced with the coronavirus, as UNESCO reports on a daily basis, as of today, 113 countries have sent children home from school, 102 of which have closed schools nationwide, with an estimated 849 million children and youth out of school. There are three periods to consider for school preparedness: in normal times, during the crisis, and after the crisis.

It is now clear that more time needs to be used to prepare teachers and systems. At the most basic level, teachers need to be prepared to deliver clear information to parents and educate children, especially the youngest ones, about hygiene management. These lessons are not only for times of crisis. Curricula based on the guidelines of the World Health Organisation’s Global School Health Initiative help students understand a potential health problem, its consequences and the types of actions required to address and prevent it. Analysis of 78 national curricula for the 2016 GEM Report, for instance, showed that between 2005 and 2015 barely one in ten countries addressed the links between global and local thinking. How long, then, until teaching also includes imparting vital lessons about disease prevention and mitigation?

Training for teachers currently assumes that lessons will be delivered in classrooms. In Quebec and elsewhere, questions are asked why ministries of education had no plan in place for the eventuality of distance teaching. If today’s events teach us one thing, it is that investment in online teaching infrastructure and teacher training to use such facilities are fundamental.

Being better prepared would also help teachers cope mentally – and help their students too. It is testament to teachers’ huge dedication to their profession that many are still risking their own health by continuing to teach the children of vital health-workers in many countries in Europe at present.

When schools close, school preparedness entails maximising the potential of online learning. Aside from schools, universities are closing too, of course, calling on professors to switch to online teaching. Just like their students, many educators are not excited by the prospect.

Reluctant some may be, but teaching is going to have to adapt to alternative scenarios. More emphasis may have to be placed on students having the tools to learn on their own and being curious to continue learning. Skype classes with 30 students even in the best resourced classrooms are challenging. New ways of working will need to be found. The longer this pandemic continues, the more likely innovative solutions may arise to meet the needs.

UNESCO organised a videoconference with ministers and their representatives from over 70 countries on 10 March about this issue, creating a crisis group from amongst them to support each other. It also pulled together a list of educational applications and platforms to help distance learning, most of which are free, and several of which support multiple languages. These include digital learning management systems like Google Classroom, which connects classes remotely, self-directed learning content, such as Byju’s, which has large repositories of educational content tailored for different grades and levels, mobile reading applications, and platforms that support live-video communication. Other online hubs for university education, such as this remarkable list of online resources in the United States, are rapidly being assembled to support educators deal with the change.

But the biggest concern is the availability of technology. Inequalities in access can further inflame inequalities in education. For so many families, device and internet availability are not options. Most education systems and schools lack knowledge on which students face such obstacles. Better preparation would entail knowing who has what access from home, and tailored responses for each. Argentina’s programme, Seguimos Educando, has been set up to respond to Covid-19. It is a multimedia education platform, providing education content and advice, which, thanks to partnerships with telephone companies, guarantees online access without cost, and with no data consumption so that all children can benefit, no matter their background. We can also learn a lot from countries that have experience of educating students in remote areas. In Western Australia, parents can home-school their children with the support of the Schools of Isolated and Distance Education, established to educate children in remote areas.

So far school closures have affected richer countries where at least using the internet for education is a real possibility. In poorer countries, which lack access to electricity altogether, low-technology approaches, whose use had weakened over the years, will need to be revisited. Kenya, for instance, runs lessons for primary and secondary school by radio. In Sierra Leone, during the Ebola outbreak, education programmes were broadcast over the radio five days a week in 30-minute sessions, with listeners able to call in with questions at the end of each session. This approach helped maintain learning despite complications by regional accents and dialects, poor radio signal coverage, and a shortage of radios and batteries.

Finally, there is the question whether available online resources reflect the curriculum and ensure teaching and learning continues smoothly when schools open again. Lists can be drawn up and sent to parents and students, but learning acquired during this period may not be reflected in assessments. What happens if students have to repeat a year? What are the future implications on their education after this much interrupted learning? There are no answers to these questions, yet.

Adjusting education systems to factor in disaster preparedness is not new. It is already seen in many countries facing earthquakes, tsunamis or cyclones, for instance, but also in the context of climate change. In short, while we do not want to admit it to ourselves, a pandemic is a likelihood we should all have been expecting more than we did. Education systems, like many other sectors right now, are turning in circles to adapt to the crisis. Their responsiveness in many cases is admirable but will need to be more effective in the future, based on a pre-existing, thought-through and evidence-based plan.

Users Today : 9

Users Today : 9 Total Users : 35459604

Total Users : 35459604 Views Today : 22

Views Today : 22 Total views : 3417994

Total views : 3417994