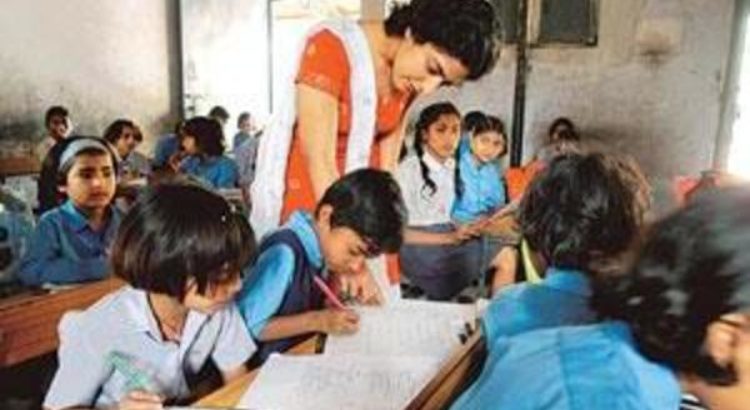

Vibrant classrooms with engaged teachers are an integral part of the New Education Policy vision

Puducherry has systematically gone about starting pre-primary classes in all its government primary schools. Anyone you ask there, they point to this levelling of the playing field as a key reason for enrolment increases in these schools, and the drop on that metric in private schools. Many teachers in Puducherry, on their own initiative, have expanded the “play-based» and “non-didactic» pedagogical approach of pre-primary classes to primary classes. Both these matters, on which action is visible in Puducherry, pre-empts the draft National Education Policy 2019 (NEP).

Gomathy was teaching class 3 at the Savarirayalu Government Primary School in Puducherry. The students were involved in addition of 3- and 4-digit numbers, working in five groups of five students each. Each group had some locally made (or very low-cost) pedagogical aids to help with the exercise. Observation made it clear that each group had a mix of students based on their comfort with the exercise. Gomathy ensured that students who were at ease with the problems did not dominate the proceedings and helped others who were struggling.

Energy was flowing in the class, with kids racing to their teacher for more problem sheets after finishing one. Gomathy explained how the school’s teachers had collectively decided to adopt a “cohort-teacher» approach, meaning the same teacher teaches a cohort of students all subjects as they progress from class to class, till they move out from primary school. This system is very useful in the early classes, when the basis of learning is primarily the relationship of trust and care between students and teachers. Learning from experience, they had tweaked this system to ensure that no cohort of students is put at a disadvantage by the cohort-teacher’s limitations.

Such vibrant, adequately resourced classrooms, with engaged teachers who have an empathetic relationship with their students, are an integral part of the NEP’s vision. So is the importance of empowerment of schools to take key educational decisions. It also highlights the centrality of the role of teachers, and the importance of “professional learning communities» of teachers.

Gomathy surprised me when she told me that she had translated Chapter 14 (National Research Foundation) of the NEP into Tamil. Her initiative and competence are not limited to school classrooms. She was as a part of a collective civil society exercise to translate the entire 484 pages of the NEP to Tamil. Later in the evening at a consultation meeting on the NEP, I saw the result of this remarkable effort—neatly printed Tamil versions of the Policy. About 40 people were involved in this effort, most of them government school teachers.

Over the course of the next three days, I was in three such meetings across the country, attended mostly by teachers and activists for public education. These were lively discussions. There were several clarifications, many constructive suggestions, a few disagreements, and a widespread acknowledgement of the much-needed transformations of Indian education that the NEP lays out. With hundreds of such points of feedback, the NEP in its final form will surely be significantly improved.

In sharp contrast to such constructive engagement is the reaction of some educationists. Many have read non-existent sections and intentions into the draft. As an example, many have seen the horrors of commercialization and privatization writ in the NEP, despite the painstaking effort of the committee to underline the importance of public education. Others are exhibiting narcissism of small differences. Both sets are being irresponsible to the very causes that they have fought for most of their lives. Because most of these causes, fought and advocated by almost everyone committed to a vibrant public education system, including these educationists, are now integral to the NEP.

Such educationists also seem to be losing sight of the fundamental nature of public policymaking—always an exercise in negotiation and balance between contending perspectives. Education in our country is a tricky battlefield. Any policy initiative that manages to stick to basic principles and succeeds in avoiding egregious mistakes or surrendering to fringe interests is definitely a success. The Kasturirangan committee has done more; while avoiding such mistakes with remarkable diligence, it has actually created a blueprint for what most in education have for decades wished for.

The final word goes to one of the wisest and most competent of public administrators in the country, who wryly commented at the end of a consultation meeting with a large group of powerful people in education, “If so many people with deep vested interests are dead against the NEP, it must be absolutely the right thing to do; let’s implement it immediately.»

Until our public intellectuals of whatever hue, liberal, left, centrist or right leaning, are more thoughtful about the reality of policymaking, are alive to the political moment, and are intellectually non-partisan, policymakers will continue to be very suspicious of experts. And that is not good for society in the long run.

Source of the article: https://www.livemint.com/opinion/columns/opinion-a-play-based-and-non-didactic-approach-to-primary-education-1563384928852.html

Users Today : 30

Users Today : 30 Total Users : 35459625

Total Users : 35459625 Views Today : 72

Views Today : 72 Total views : 3418044

Total views : 3418044