Por GEM Report

Resumen:

El equipo del Informe GEM es muy aplaudible por centrarse en los roles de los actores no estatales en la educación en su edición de 2021, cuya consulta aún está abierta. Entre estos actores hay tutores privados. Pueden ser estudiantes universitarios y otros que trabajan informalmente como tutores privados, maestros en escuelas públicas que desempeñan funciones adicionales como tutores privados y empresarios que operan centros de tutoría como empresas y cadenas independientes. La tutoría complementaria privada se conoce ampliamente como educación paralela porque gran parte de ella imita la escolarización convencional. En todo el mundo , muchos millones de estudiantes reciben alguna forma de educación en la sombra cada día. El Informe GEM 2017/8 estimó que el tamaño del mercado superaría los US $ 227 mil millones para 2022. A nivel mundial, la República de Corea es mejor conocida por la escala de la educación en la sombra. En 2018, el 82% de los estudiantes de primaria recibían apoyo complementario junto con el 70% de los estudiantes de secundaria y el 65% de los estudiantes de secundaria general. La mayor parte de este apoyo fue en instituciones llamadas hagwons, que se parecían al juku por el que Japón es famoso. Las instituciones de contraparte también son muy comunes en China continental y Hong Kong. Pero la tutoría complementaria privada no es solo un fenómeno del este asiático. También se ha expandido notablemente en Europa, por ejemplo. Una actualización de 2020 de un informe de 2011 para la Comisión Europea mostró que la educación en la sombra es cada vez más visible, incluso en los países escandinavos donde anteriormente había sido insignificante. Inglaterra y Gales, por ejemplo, tenían poca tradición de tutoría suplementaria privada en el pasado, al menos para estudiantes regulares en escuelas estatales; pero una encuesta de 2019 de estudiantes de 11 a 16 años realizada por Sutton Trust descubrió que el 27% de los encuestados en la muestra total había recibido tutoría privada en algún momento de sus carreras, aumentando al 41% entre los encuestados en Londres. Las estadísticas de Egipto e India muestran que la tutoría complementaria también es evidente en los países de bajos ingresos. Una encuesta nacional egipcia citada por Sieverding et al. (2019) indicaron que el 36% de los alumnos de primaria, el 53% de secundaria inferior y el 84% de los alumnos de secundaria general estaban recibiendo tutoría complementaria. Y en el estado de Bengala Occidental de la India, el 70% de los estudiantes rurales en los grados 1-5 y el 77% de los estudiantes rurales en los grados 6-8 muestreados por Pratham (2019) estaban recibiendo tutoría suplementaria privada. Las proporciones para estudiantes urbanos probablemente habrían sido aún mayores. La evidencia actualizada para África se presentará en el Informe GEM 2021.

The GEM Report team is much to be applauded for focusing on the roles of non-state actors in education in its 2021 edition – the

consultation for which is still open. Among these actors are private tutors. They may be university students and others who work informally as private tutors, teachers in public schools who take additional roles as private tutors, and entrepreneurs who operate tutorial centres as stand-alone enterprises and chains.

Private supplementary tutoring is widely known as shadow education because much of it mimics mainstream schooling.

Across the world, many millions of students receive some form of

shadow education each day. The 2017/8 GEM Report

estimated that the size of the market would surpass US$227 billion by 2022.

Globally, the Republic of Korea is best known for the scale of shadow education. In 2018, 82% of elementary-school students were receiving supplementary support alongside 70% of middle-school and 65% of general-high-school students. Most of this support was in institutions called hagwons, which resembled the juku for which Japan is famous. Counterpart institutions are also very common in Mainland China and Hong Kong.

But private supplementary tutoring is not just an East Asian phenomenon. It has also expanded remarkably in Europe, for example. A 2020

update of a 2011

report for the European Commission showed that shadow education is increasingly visible, including in Scandinavian countries where it had previously been negligible. England and Wales, for example, had little tradition of private supplementary tutoring in the past, at least for regular students in state schools; but a 2019

survey of students aged 11-16 by the Sutton Trust found that 27% of respondents in the total sample had received private tutoring at some point in their careers, rising to 41% among respondents in London.

Statistics from Egypt and India show that supplementary tutoring is also evident in lower-income countries. An Egyptian national survey cited by

Sieverding et al. (2019) indicated that 36% of primary, 53% of lower-secondary, and 84% of general-secondary students were receiving supplementary tutoring. And in India’s West Bengal State, 70% of rural students in Grades 1-5 and 77% of rural students in Grades 6-8 sampled by

Pratham (2019) were receiving private supplementary tutoring. Proportions for urban students would likely have been even greater. Updated evidence for Africa will be presented in the 2021 GEM Report.

The format for such tutoring may be very varied. It can be provided one-to-one, in small groups, or in large lecture theatres. Increasingly, tutoring is delivered over the internet. Such tutoring can bridge rural-urban divides, but also raises questions about content, pedagogy and regulation.

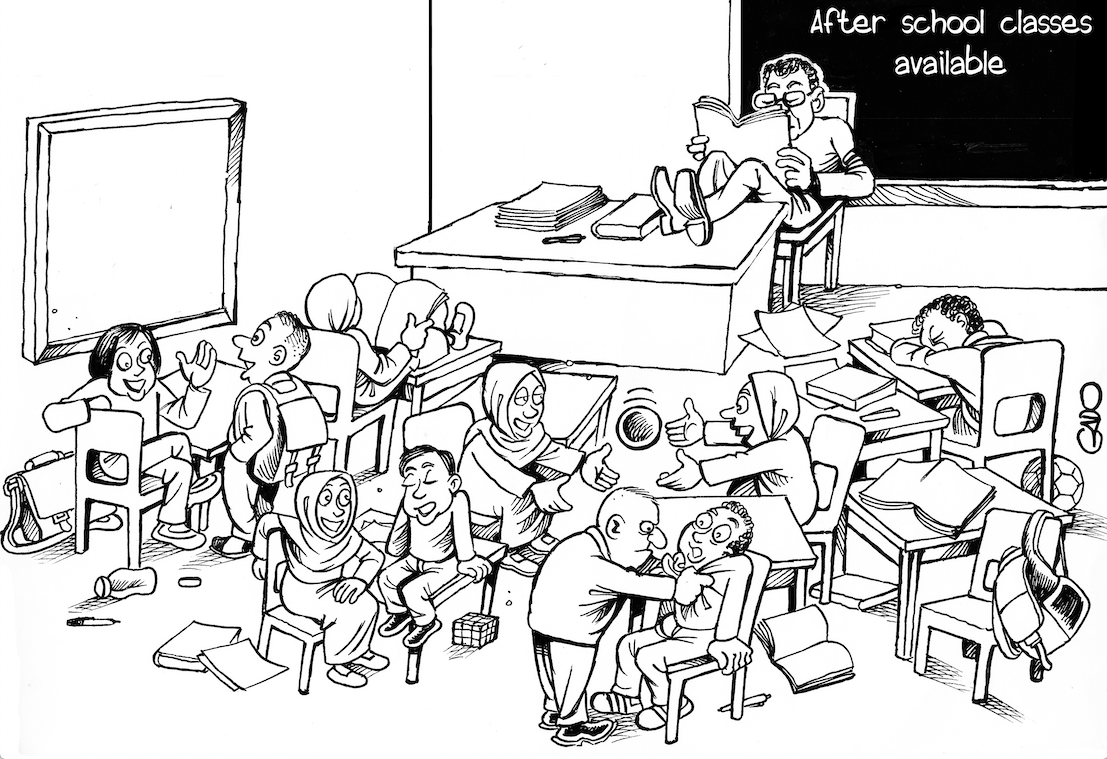

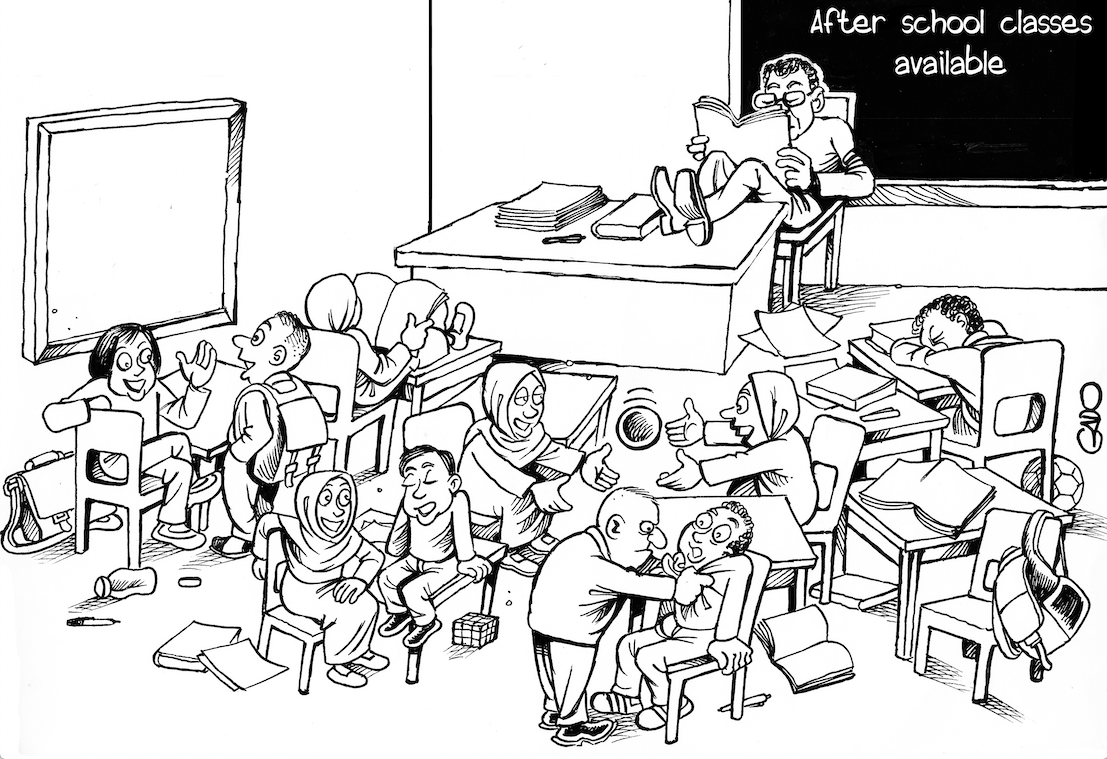

Source: 2017/8 GEM Report. Credit: GADO

The issues also include questions about the roles of mainstream teachers. Public school teachers who provide supplementary tutoring can increase their incomes and perhaps are more likely to stay in the profession. However, in under-regulated settings teachers may be tempted to short-change their mainstream teaching in order to force their students to come to private classes after school. This pattern raises issues of corruption. And even in settings where teachers do not themselves provide tutoring, schools commonly assume that the majority of students gain extra support, and then themselves fail to provide all the support that they should.

Private supplementary tutoring is also a financial burden for millions of families, and raises major issues about social inequalities. The

2017/8 GEM Report indicated that the richest families in Viet Nam spent 14 times more on private tutoring than the poorest; and in 2015, 35% of United Kingdom parents who did not pay for private tutoring cited cost.

Shadow education is a growing phenomenon, and it must be analysed anew in the 2021 GEM Report on non-state actors. The implications of shadow education must be more transparent in connection with the

SDG4 goal of inclusive and equitable quality education for all.

Fuente: https://gemreportunesco.wordpress.com/2020/02/13/private-supplementary-tutoring-a-global-phenomenon-with-far-reaching-implications/

Users Today : 108

Users Today : 108 Total Users : 35459574

Total Users : 35459574 Views Today : 170

Views Today : 170 Total views : 3417928

Total views : 3417928