Dr. Henry Giroux

What happens to democracy when the president of the United States labels critical media outlets as «enemies of the people» and disparages the search for truth with the blanket term «fake news»? What happens to democracy when individuals and groups are demonized on the basis of their religion? What happens to a society when critical thinking becomes an object of contempt? What happens to a social order ruled by an economics of contempt that blames the poor for their condition and subjects them to a culture of shaming? What happens to a polity when it retreats into private silos and becomes indifferent to the use of language deployed in the service of a panicked rage — language that stokes anger but ignores issues that matter? What happens to a social order when it treats millions of undocumented immigrants as disposable, potential terrorists and «criminals»? What happens to a country when the presiding principles of its society are violence and ignorance?

What happens is that democracy withers and dies, both as an ideal and as a reality.

In the present moment, it becomes particularly important for educators and concerned citizens all over the world to protect and enlarge the critical formative educational cultures and public spheres that make democracy possible. Alternative newspapers, progressive media, screen culture, online media and other educational sites and spaces in which public pedagogies are produced constitute the political and educational elements of a vibrant, critical formative culture within a wide range of public spheres. Critical formative cultures are crucial in producing the knowledge, values, social relations and visions that help nurture and sustain the possibility to think critically, engage in political dissent, organize collectively and inhabit public spaces in which alternative and critical theories can be developed.

At the core of thinking dangerously is the recognition that education is central to politics and that a democracy cannot survive without informed citizens.

Authoritarian societies do more than censor; they punish those who engage in what might be called dangerous thinking. At the core of thinking dangerously is the recognition that education is central to politics and that a democracy cannot survive without informed citizens. Critical and dangerous thinking is the precondition for nurturing the ethical imagination that enables engaged citizens to learn how to govern rather than be governed. Thinking with courage is fundamental to a notion of civic literacy that views knowledge as central to the pursuit of economic and political justice. Such thinking incorporates a set of values that enables a polity to deal critically with the use and effects of power, particularly through a developed sense of compassion for others and the planet. Thinking dangerously is the basis for a formative and educational culture of questioning that takes seriously how imagination is key to the practice of freedom. Thinking dangerously is not only the cornerstone of critical agency and engaged citizenship, it’s also the foundation for a working democracy.

Education and the Struggle for Liberation

Any viable attempt at developing a democratic politics must begin to address the role of education and civic literacy as central to politics itself. Education is also vital to the creation of individuals capable of becoming critical social agents willing to struggle against injustices and develop the institutions that are crucial to the functioning of a substantive democracy. One way to begin such a project is to address the meaning and role of higher education (and education in general) as part of the broader struggle for freedom.

The reach of education extends from schools to diverse cultural apparatuses, such as the mainstream media, alternative screen cultures and the expanding digital screen culture. Far more than a teaching method, education is a moral and political practice actively involved not only in the production of knowledge, skills and values but also in the construction of identities, modes of identification, and forms of individual and social agency. Accordingly, education is at the heart of any understanding of politics and the ideological scaffolding of those framing mechanisms that mediate our everyday lives.

Across the globe, the forces of free-market fundamentalism are using the educational system to reproduce a culture of privatization, deregulation and commercialization while waging an assault on the historically guaranteed social provisions and civil rights provided by the welfare state, higher education, unions, reproductive rights and civil liberties. All the while, these forces are undercutting public faith in the defining institutions of democracy.

This grim reality was described by Axel Honneth in his book Pathologies of Reason as a «failed sociality» characteristic of an increasing number of societies in which democracy is waning — a failure in the power of the civic imagination, political will and open democracy. It is also part of a politics that strips the social of any democratic ideals and undermines any understanding of education as a public good and pedagogy as an empowering practice: a practice that can act directly upon the conditions that bear down on our lives in order to change them when necessary.

As Chandra Mohanty points out:

At its most ambitious, [critical] pedagogy is an attempt to get students to think critically about their place in relation to the knowledge they gain and to transform their world view fundamentally by taking the politics of knowledge seriously. It is a pedagogy that attempts to link knowledge, social responsibility, and collective struggle. And it does so by emphasizing the risks that education involves, the struggles for institutional change, and the strategies for challenging forms of domination and by creating more equitable and just public spheres within and outside of educational institutions.

At its core, critical pedagogy raises issues of how education might be understood as a moral and political practice, and not simply a technical one. At stake here is the issue of meaning and purpose in which educators put into place the pedagogical conditions for creating a public sphere of citizens who are able to exercise power over their own lives. Critical pedagogy is organized around the struggle over agency, values and social relations within diverse contexts, resources and histories. Its aim is producing students who can think critically, be considerate of others, take risks, think dangerously and imagine a future that extends and deepens what it means to be an engaged citizen capable of living in a substantive democracy.

What work do educators have to do to create the economic, political and ethical conditions necessary to endow young people and the general public with the capacities to think, question, doubt, imagine the unimaginable and defend education as essential for inspiring and energizing the citizens necessary for the existence of a robust democracy? This is a particularly important issue at a time when higher education is being defunded and students are being punished with huge tuition hikes and financial debts, while being subjected to a pedagogy of repression that has taken hold under the banner of reactionary and oppressive educational reforms pushed by right-wing billionaires and hedge fund managers. Addressing education as a democratic public sphere is also crucial as a theoretical tool and political resource for fighting against neoliberal modes of governance that have reduced faculty all over the United States to adjuncts and part-time workers with few or no benefits. These workers bear the brunt of a labor process that is as exploitative as it is disempowering.

Educators Need a New Language for the Current Era

Given the crisis of education, agency and memory that haunts the current historical conjuncture, educators need a new language for addressing the changing contexts of a world in which an unprecedented convergence of resources — financial, cultural, political, economic, scientific, military and technological — is increasingly used to exercise powerful and diverse forms of control and domination. Such a language needs to be self-reflective and directive without being dogmatic, and needs to recognize that pedagogy is always political because it is connected to the acquisition of agency. In this instance, making the pedagogical more political means being vigilant about what Gary Olson and Lynn Worsham describe as «that very moment in which identities are being produced and groups are being constituted, or objects are being created.» At the same time it means educators need to be attentive to those practices in which critical modes of agency and particular identities are being denied.

In part, this suggests developing educational practices that not only inspire and energize people but are also capable of challenging the growing number of anti-democratic practices and policies under the global tyranny of casino capitalism. Such a vision demands that we imagine a life beyond a social order immersed in massive inequality, endless assaults on the environment, and the elevation of war and militarization to the highest and most sanctified national ideals. Under such circumstances, education becomes more than an obsession with accountability schemes and the bearer of an audit culture (a culture characterized by a call to be objective and an unbridled emphasis on empiricism). Audit cultures support conservative educational policies driven by market values and an unreflective immersion in the crude rationality of a data-obsessed market-driven society; as such, they are at odds with any viable notion of a democratically inspired education and critical pedagogy. In addition, viewing public and higher education as democratic public spheres necessitates rejecting the notion that they should be reduced to sites for training students for the workforce — a reductive vision now being imposed on public education by high-tech companies such as Facebook, Netflix and Google, which want to encourage what they call the entrepreneurial mission of education, which is code for collapsing education into training.

Education can all too easily become a form of symbolic and intellectual violence that assaults rather than educates. Examples of such violence can be seen in the forms of an audit culture and empirically-driven teaching that dominates higher education. These educational projects amount to pedagogies of repression and serve primarily to numb the mind and produce what might be called dead zones of the imagination. These are pedagogies that are largely disciplinary and have little regard for contexts, history, making knowledge meaningful, or expanding what it means for students to be critically engaged agents. Of course, the ongoing corporatization of the university is driven by modes of assessment that often undercut teacher autonomy and treat knowledge as a commodity and students as customers, imposing brutalizing structures of governance on higher education. Under such circumstances, education defaults on its democratic obligations and becomes a tool of control and powerlessness, thereby deadening the imagination.

The fundamental challenge facing educators within the current age of an emerging authoritarianism worldwide is to create those public spaces for students to address how knowledge is related to the power of both self-definition and social agency. In part, this suggests providing students with the skills, ideas, values and authority necessary for them not only to be well-informed and knowledgeable across a number of traditions and disciplines, but also to be able to invest in the reality of a substantive democracy. In this context, students learn to recognize anti-democratic forms of power. They also learn to fight deeply rooted injustices in a society and world founded on systemic economic, racial and gendered inequalities.

Education in this sense speaks to the recognition that any pedagogical practice presupposes some notion of the future, prioritizes some forms of identification over others and values some modes of knowing over others. (Think about how business schools are held in high esteem while schools of education are often disparaged.) Moreover, such an education does not offer guarantees. Instead, it recognizes that its own policies, ideology and values are grounded in particular modes of authority, values and ethical principles that must be constantly debated for the ways in which they both open up and close down democratic relations, values and identities.

The notion of a neutral, objective education is an oxymoron. Education and pedagogy do not exist outside of ideology, values and politics. Ethics, when it comes to education, demand an openness to the other, a willingness to engage a «politics of possibility» through a continual critical engagement with texts, images, events and other registers of meaning as they are transformed into pedagogical practices both within and outside of the classroom. Education is never innocent: It is always implicated in relations of power and specific visions of the present and future. This suggests the need for educators to rethink the cultural and ideological baggage they bring to each educational encounter. It also highlights the necessity of making educators ethically and politically accountable and self-reflective for the stories they produce, the claims they make upon public memory, and the images of the future they deem legitimate. Education in this sense is not an antidote to politics, nor is it a nostalgic yearning for a better time or for some «inconceivably alternative future.» Instead, it is what Terry Eagleton describes in his book The Idea of Culture as an «attempt to find a bridge between the present and future in those forces within the present which are potentially able to transform it.»

One of the most serious challenges facing administrators, faculty and students in colleges and universities is the task of developing a discourse of both critique and possibility. This means developing discourses and pedagogical practices that connect reading the word with reading the world, and doing so in ways that enhance the capacities of young people to be critical agents and engaged citizens.

Reviving the Social Imagination

Educators, students and others concerned about the fate of higher education need to mount a spirited attack against the managerial takeover of the university that began in the late 1970s with the emergence of a market-driven ideology, what can be called neoliberalism, which argues that market principles should govern not just the economy but all of social life, including education. Central to such a recognition is the need to struggle against a university system developed around the reduction in faculty and student power, the replacement of a culture of cooperation and collegiality with a shark-like culture of competition, the rise of an audit culture that has produced a very limited notion of regulation and evaluation, and the narrow and harmful view that students are clients and colleges «should operate more like private firms than public institutions, with an onus on income generation,» as Australian scholar Richard Hill puts it in his Arena article «Against the Neoliberal University.» In addition, there is an urgent need for guarantees of full-time employment and protections for faculty while viewing knowledge as a public asset and the university as a public good.

In any democratic society, education should be viewed as a right, not an entitlement. Educators need to produce a national conversation in which higher education can be defended as a public good.

With these issues in mind, let me conclude by pointing to six further considerations for change.

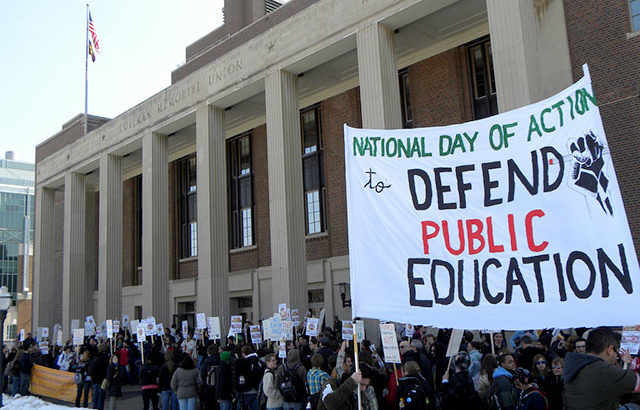

First, there is a need for what can be called a revival of the social imagination and the defense of the public good, especially in regard to higher education, in order to reclaim its egalitarian and democratic impulses. This revival would be part of a larger project to, as Stanley Aronowitz writes in Tikkun, «reinvent democracy in the wake of the evidence that, at the national level, there is no democracy — if by ‘democracy’ we mean effective popular participation in the crucial decisions affecting the community.» One step in this direction would be for young people, intellectuals, scholars and others to go on the offensive against what Gene R. Nichol has described as the conservative-led campaign «to end higher education’s democratizing influence on the nation.» Higher education should be harnessed neither to the demands of the warfare state nor to the instrumental needs of corporations. Clearly, in any democratic society, education should be viewed as a right, not an entitlement. Educators need to produce a national conversation in which higher education can be defended as a public good and the classroom as a site of engaged inquiry and critical thinking, a site that makes a claim on the radical imagination and builds a sense of civic courage. At the same time, the discourse on defining higher education as a democratic public sphere would provide the platform for moving on to the larger issue of developing a social movement in defense of public goods.

Second, I believe that educators need to consider defining pedagogy, if not education itself, as central to producing those democratic public spheres that foster an informed citizenry. Pedagogically, this points to modes of teaching and learning capable of enacting and sustaining a culture of questioning, and enabling the advancement of what Kristen Case calls «moments of classroom grace.» Moments of grace in this context are understood as moments that enable a classroom to become a place to think critically, ask troubling questions and take risks, even though that may mean transgressing established norms and bureaucratic procedures.

Pedagogies of classroom grace should provide the conditions for students and others to reflect critically on commonsense understandings of the world and begin to question their own sense of agency, relationships to others, and relationships to the larger world. This can be linked to broader pedagogical imperatives that ask why we have wars, massive inequality, and a surveillance state. There is also the issue of how everything has become commodified, along with the withering of a politics of translation that prevents the collapse of the public into the private. This is not merely a methodical consideration but also a moral and political practice because it presupposes the development of critically engaged students who can imagine a future in which justice, equality, freedom and democracy matter.

Such pedagogical practices are rich with possibilities for understanding the classroom as a space that ruptures, engages, unsettles and inspires. Education as democratic public space cannot exist under modes of governance dominated by a business model, especially one that subjects faculty to a Walmart model of labor relations designed «to reduce labor costs and to increase labor servility,» as Noam Chomsky writes. In the US, over 70 percent of faculty occupy nontenured and part-time positions, many without benefits and with salaries so low that they qualify for food stamps. Faculty need to be given more security, full-time jobs, autonomy and the support they need to function as professionals. While many other countries do not emulate this model of faculty servility, it is part of a neoliberal legacy that is increasingly gaining traction across the globe.

Third, educators need to develop a comprehensive educational program that would include teaching students how to live in a world marked by multiple overlapping modes of literacy extending from print to visual culture and screen cultures. What is crucial to recognize here is that it is not enough to teach students to be able to interrogate critically screen culture and other forms of aural, video and visual representation. They must also learn how to be cultural producers. This suggests developing alternative public spheres, such as online journals, television shows, newspapers, zines and any other platform in which different modes of representation can be developed. Such tasks can be done by mobilizing the technological resources and platforms that many students are already familiar with.

Teaching cultural production also means working with one foot in existing cultural apparatuses in order to promote unorthodox ideas and views that would challenge the affective and ideological spaces produced by the financial elite who control the commanding institutions of public pedagogy in North America. What is often lost by many educators and progressives is that popular culture is a powerful form of education for many young people, and yet it is rarely addressed as a serious source of knowledge. As Stanley Aronowitz has observed in his book Against Schooling, «theorists and researchers need to link their knowledge of popular culture, and culture in the anthropological sense — that is, everyday life, with the politics of education.»

Fourth, academics, students, community activists, young people and parents must engage in an ongoing struggle for the right of students to be given a free formidable and critical education not dominated by corporate values, and for young people to have a say in the shaping of their education and what it means to expand and deepen the practice of freedom and democracy. College and university education, if taken seriously as a public good, should be virtually tuition-free, at least for the poor, and utterly affordable for everyone else. This is not a radical demand; countries such as Germany, France, Norway, Finland and Brazil already provide this service for young people.

Accessibility to higher education is especially crucial at a time when young people have been left out of the discourse of democracy. They often lack jobs, a decent education, hope and any semblance of a future better than the one their parents inherited. Facing what Richard Sennett calls the «specter of uselessness,» they are a reminder of how finance capital has abandoned any viable vision of the future, including one that would support future generations. This is a mode of politics and capital that eats its own children and throws their fate to the vagaries of the market. The ecology of finance capital only believes in short-term investments because they provide quick returns. Under such circumstances, young people who need long-term investments are considered a liability.

Fifth, educators need to enable students to develop a comprehensive vision of society that extends beyond single issues. It is only through an understanding of the wider relations and connections of power that young people and others can overcome uninformed practice, isolated struggles, and modes of singular politics that become insular and self-sabotaging. In short, moving beyond a single-issue orientation means developing modes of analyses that connect the dots historically and relationally. It also means developing a more comprehensive vision of politics and change. The key here is the notion of translation — that is, the need to translate private troubles into broader public issues.

Sixth, another serious challenge facing educators who believe that colleges and universities should function as democratic public spheres is the task of developing a discourse of both critique and possibility, or what I have called a discourse of educated hope. In taking up this project, educators and others should attempt to create the conditions that give students the opportunity to become critical and engaged citizens who have the knowledge and courage to struggle in order to make desolation and cynicism unconvincing and hope practical. Critique is crucial to break the hold of commonsense assumptions that legitimate a wide range of injustices. But critique is not enough. Without a simultaneous discourse of hope, it can lead to an immobilizing despair or, even worse, a pernicious cynicism. Reason, justice and change cannot blossom without hope. Hope speaks to imagining a life beyond capitalism, and combines a realistic sense of limits with a lofty vision of demanding the impossible. Educated hope taps into our deepest experiences and longing for a life of dignity with others, a life in which it becomes possible to imagine a future that does not mimic the present. I am not referring to a romanticized and empty notion of hope, but to a notion of informed hope that faces the concrete obstacles and realities of domination but continues the ongoing task of what Andrew Benjamin describes as «holding the present open and thus unfinished.»

The discourse of possibility looks for productive solutions and is crucial in defending those public spheres in which civic values, public scholarship and social engagement allow for a more imaginative grasp of a future that takes seriously the demands of justice, equity and civic courage. Democracy should encourage, even require, a way of thinking critically about education — one that connects equity to excellence, learning to ethics, and agency to the imperatives of social responsibility and the public good.

History is open. It is time to think otherwise in order to act otherwise.

My friend, the late Howard Zinn, rightly insisted that hope is the willingness «to hold out, even in times of pessimism, the possibility of surprise.» To add to this eloquent plea, I would say that history is open. It is time to think otherwise in order to act otherwise, especially if as educators we want to imagine and fight for alternative futures and horizons of possibility.

Source:

http://www.truth-out.org/opinion/item/41058-thinking-dangerously-the-role-of-higher-education-in-authoritarian-times

Users Today : 19

Users Today : 19 Total Users : 35468209

Total Users : 35468209 Views Today : 22

Views Today : 22 Total views : 3534195

Total views : 3534195