31 de Diciembre de 2016. Fuente: PewResearch Center

Resumen: Basándose en encuestas realizadas en 151 países, un estudio analiza el logro educativo entre creyentes de las principales religiones monoteístas del planeta. ¿Existirá una relación entre educación y religión? Veamos que reseña el informe del estudio.

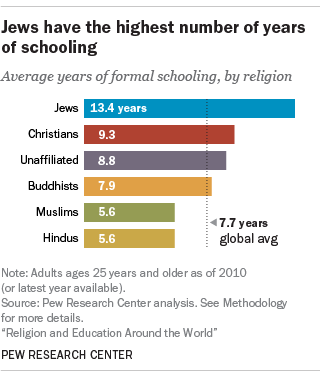

Jews are more highly educated than any other major religious group around the world, while Muslims and Hindus tend to have the fewest years of formal schooling, according to a Pew Research Center global demographic study that shows wide disparities in average educational levels among religious groups.

These gaps in educational attainment are partly a function of where religious groups are concentrated throughout the world. For instance, the vast majority of the world’s Jews live in the United States and Israel – two economically developed countries with high levels of education overall. And low levels of attainment among Hindus reflect the fact that 98% of Hindu adults live in the developing countries of India, Nepal and Bangladesh.

But there also are important differences in educational attainment among religious groups living in the same region, and even the same country. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, Christians generally have higher average levels of education than Muslims. Some social scientists have attributed this gap primarily to historical factors, including missionary activity during colonial times. (For more on theories about religion’s impact on educational attainment, see Chapter 7.)

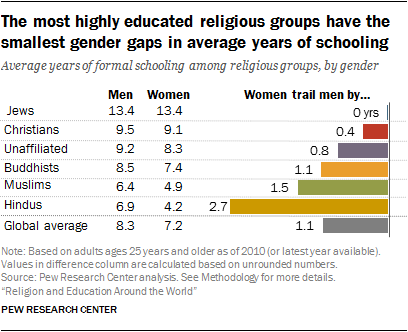

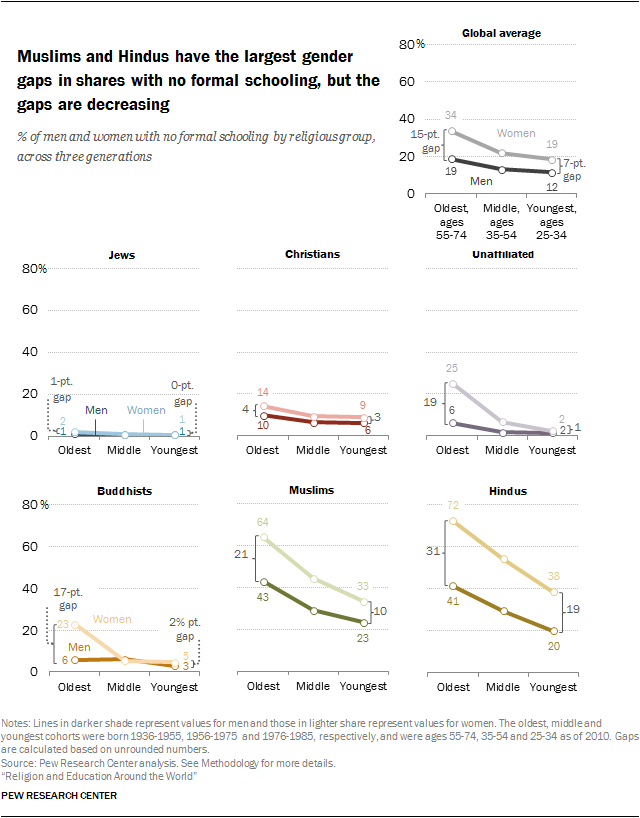

Drawing on census and survey data from 151 countries, the study also finds large gender gaps in educational attainment within some major world religions. For example, Muslim women around the globe have an average of 4.9 years of schooling, compared with 6.4 years among Muslim men. And formal education is especially low among Hindu women, who have 4.2 years of schooling on average, compared with 6.9 years among Hindu men.

Drawing on census and survey data from 151 countries, the study also finds large gender gaps in educational attainment within some major world religions. For example, Muslim women around the globe have an average of 4.9 years of schooling, compared with 6.4 years among Muslim men. And formal education is especially low among Hindu women, who have 4.2 years of schooling on average, compared with 6.9 years among Hindu men.

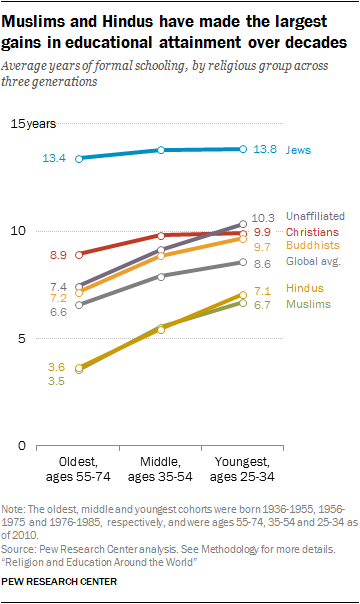

Yet many of these disparities appear to be decreasing over time, as the religious groups with the lowest average levels of education – Muslims and Hindus – have made the biggest educational gains in recent generations, and as the gender gaps within some religions have diminished, according to Pew Research Center’s analysis.

At present, Jewish adults (ages 25 and older) have a global average of 13 years of formal schooling, compared with approximately nine years among Christians, eight years among Buddhists and six years among Muslims and Hindus. Religiously unaffiliated adults – those who describe their religion as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” – have spent an average of nine years in school, a little less than Christian adults worldwide.1

At present, Jewish adults (ages 25 and older) have a global average of 13 years of formal schooling, compared with approximately nine years among Christians, eight years among Buddhists and six years among Muslims and Hindus. Religiously unaffiliated adults – those who describe their religion as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” – have spent an average of nine years in school, a little less than Christian adults worldwide.1

But the number of years of schooling received by the average adult in all the religious groups studied has been rising in recent decades, with the greatest overall gains made by the groups that had lagged furthest behind.

For instance, the youngest Hindu adults in the study (those born between 1976 and 1985) have spent an average of 7.1 years in school, nearly double the amount of schooling received by the oldest Hindus in the study (those born between 1936 and 1955). The youngest Muslims have made similar gains, receiving approximately three more years of schooling, on average, than their counterparts born a few decades earlier, as have the youngest Buddhists, who acquired 2.5 more years of schooling.

Over the same time frame, by contrast, Christians gained an average of just one more year of schooling, and Jews recorded an average gain of less than half a year of additional schooling.

Meanwhile, the youngest generation of religiously unaffiliated adults – sometimes called religious “nones” – in the study has gained so much ground (2.9 more years of schooling than the oldest generation of religious “nones” analyzed) that it has surpassed Christians in average number of years of schooling worldwide (10.3 years among the youngest unaffiliated adults vs. 9.9 years among the youngest Christians).

Gender gaps also are narrowing somewhat. In the oldest generation, across all the major religious groups, men received more years of schooling, on average, than women. But the youngest generations of Christian, Buddhist and unaffiliated women have achieved parity with their male counterparts in average years of schooling. And among the youngest Jewish adults, Jewish women have spent nearly one more year in school, on average, than Jewish men.

These are among the key findings of Pew Research Center’s new demographic study. A prior study by researchers at an Austrian institute, the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Human Capital, looked at differences in educational attainment by age and gender.2 The new study is the first comprehensive examination of differences in educational levels by religion. Wittgenstein Centre researchers Michaela Potančoková and Marcin Stonawski collaborated with Pew Research Center researchers to compile and standardize this data.

Religions vary in educational attainment

About one-in-five adults globally – but twice as many Muslims and Hindus – have received no schooling at all

Despite recent gains by young adults, formal schooling is neither universal nor equal around the world. The global norm is barely more than a primary education – an average of about eight years of formal schooling for men and seven years for women.

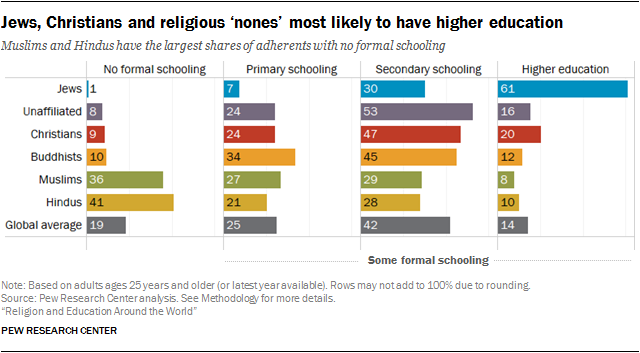

At the high end of the spectrum, 14% of adults ages 25 and older (including 15% of men and 13% of women) have a university degree or some other kind of higher education, such as advanced vocational training after high school. But an even larger percentage – about one-in-five adults (19%) worldwide, or more than 680 million people – have no formal schooling at all.

Education levels vary a great deal by religion. About four-in-ten Hindus (41%) and more than one-third of Muslims (36%) in the study have no formal schooling. In other religious groups, the shares without any schooling range from 10% of Buddhists to 1% of Jews, while a majority of Jewish adults (61%) have post-secondary degrees.3

Hindus and Muslims have made big advances in educational attainment

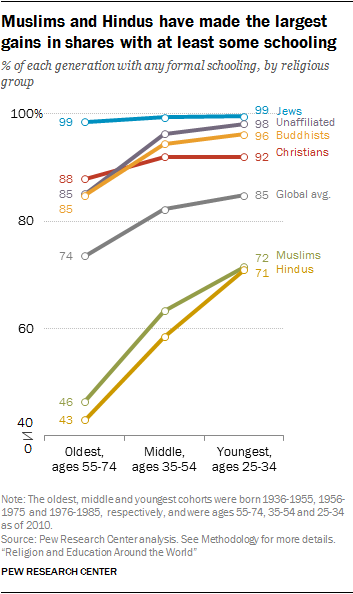

The study finds the religious groups with the lowest levels of education are also the ones that have made the biggest gains in educational attainment in recent decades.

Over three recent generations, the share of Hindus with at least some formal schooling rose by 28 percentage points, from 43% among the oldest Hindus in the study to 71% among the youngest. Muslims, meanwhile, registered a 25-point increase, from 46% among the oldest Muslims to 72% among the youngest.

Over three recent generations, the share of Hindus with at least some formal schooling rose by 28 percentage points, from 43% among the oldest Hindus in the study to 71% among the youngest. Muslims, meanwhile, registered a 25-point increase, from 46% among the oldest Muslims to 72% among the youngest.

Christians, Buddhists and religious “nones” have made more modest gains in basic education, but they started from a higher base. Among the oldest generation in the study, large majorities of these three religious groups received at least some formal education; among the youngest Christians, Buddhists and religious “nones,” more than nine-in-ten have received at least some schooling.

The share of Jews with at least some schooling has remained virtually universal across generations at 99%.

Declining gender gaps in formal education

In this study, more women than men have no formal education: As of 2010, an estimated 432 million women (23% of all women ages 25 and older) and 250 million men (14% of all men) lacked any formal education.

In some religious groups, the gender gaps in acquiring any formal education are particularly large. For example, just over half of Hindu women (53%) have received no formal schooling, compared with 29% of Hindu men, a difference of 24 percentage points. Among Muslims worldwide, 43% of women and 30% of men have no formal schooling, a 13-point gap. In other religions, the gender differences in the shares with no formal schooling are smaller, ranging from 9 points among the religiously unaffiliated to just 1 point among Jews.

But Hindus have substantially narrowed the gender gap in primary schooling, as shares of Hindu women with no formal schooling decreased across the three generations studied. Among the oldest Hindus, 72% of women and 41% of men have no formal schooling. But among the youngest Hindus in the study, the gender gap is smaller, as 38% of women and 20% of men have no formal schooling.

Muslims also have reduced the gender gap across generations by 11 percentage points. But in the youngest generation, a 10-point difference remains: 33% of Muslim women and 23% of Muslim men have no formal schooling. Among religiously unaffiliated adults and Buddhists worldwide, meanwhile, the gender gap in the shares with no formal schooling has virtually disappeared.

Reversal of some gender gaps in higher education

Worldwide, among all adults in the study, slightly more men than women hold post-secondary degrees (15% vs. 13%). But across generations, women have been outpacing men in reaching higher levels of education. As a result, in the youngest generation, the share of women with post-secondary degrees is comparable to the share of men (17% each).

In the youngest generation of three faith groups – Jews, Christians and the religiously unaffiliated – the gender gap in higher education has actually reversed. The biggest reversal has happened among Jews. Among the oldest generation of Jews, more men (66%) than women (59%) hold post-secondary degrees. But among the youngest Jewish adults worldwide, 69% of women and 57% of men have such degrees. In other words, a 7-point gender gap in the oldest generation (with more men than women holding advanced degrees) is now a 12-point gender gap in the other direction, with more women than men in the youngest generation of Jews holding degrees. (See Chapter 6 for details.)

Christians and religiously unaffiliated people have experienced similar – although not as dramatic – reversals of the gender gap in post-secondary education. Among Christians, the gender gap among those in the oldest adult cohort – 21% of men with higher education vs. 17% of women – has flipped among the youngest so that more women than men now hold degrees (25% of women vs. 20% of men). Similarly, among religiously unaffiliated people, the 3-point gender gap in the oldest generation (with more men than women having higher education) is now a 3-point gap in the other direction in the youngest generation, with more women than men earning post-secondary degrees.

Meanwhile, the gender gap in higher education has narrowed for Buddhists (by 5 points) and Muslims (by 3 points). Among the youngest generations in those groups, roughly equal shares of women and men hold higher degrees – 19% each among Buddhists and 11% and 9% among Muslim men and women, respectively. The gender gap in post-secondary education among Hindus has held steady across generations. In the youngest cohort of Hindus, more men than women still have post-secondary degrees (17% of men vs. 11% of women).

Both religion and region matter for educational attainment

Within the world’s major religious groups, there are often large variations in educational attainment depending on the country or region of the world in which adherents live. Muslims in Europe, for example, have more years of schooling, on average, than Muslims in the Middle East. This is because education levels are affected by many factors other than religion, including socioeconomic conditions, government resources and migration policies, the presence or absence of armed conflict and the prevalence of child labor and marriage.

At the same time, this study finds that even under the same regional or national conditions, there often are differences in education attainment among those within religious groups. Here are some findings from this report that illustrate both the diversity within the same religious group across different regions of the world, and the diversity within the same region among religious groups:

There is a large and pervasive gap in educational attainment between Muslims and Christians in sub-Saharan Africa. By all attainment measures, Muslim adults in the region – both women and men – are far less educated than their Christian counterparts. For instance, Muslims are more than twice as likely as Christians in sub-Saharan Africa to have no formal schooling (65% vs. 30%). Moreover, despite growth in the share of adults with any formal schooling in recent decades, the Muslim-Christian attainment gap has widened across generations, largely because Muslims have not kept pace with educational gains made by Christians. (See Chapter 1 for more on the Muslim-Christian gap in sub-Saharan Africa, and Chapter 7 for a discussion of possible explanations.)

There is a large and pervasive gap in educational attainment between Muslims and Christians in sub-Saharan Africa. By all attainment measures, Muslim adults in the region – both women and men – are far less educated than their Christian counterparts. For instance, Muslims are more than twice as likely as Christians in sub-Saharan Africa to have no formal schooling (65% vs. 30%). Moreover, despite growth in the share of adults with any formal schooling in recent decades, the Muslim-Christian attainment gap has widened across generations, largely because Muslims have not kept pace with educational gains made by Christians. (See Chapter 1 for more on the Muslim-Christian gap in sub-Saharan Africa, and Chapter 7 for a discussion of possible explanations.)- Also in sub-Saharan Africa, the Muslim gender gap in education has remained largely unchanged across generations – and even widened slightly by some measures of attainment analyzed in this study. Although the youngest Muslim women in this region are making educational gains compared with their elders, they are making them at a slightly slower rate than their male peers. This pattern differs from some other regions, where Muslim women are generally making educational gains at a faster pace than Muslim men, thus narrowing the gender gap. (See Chapter 1 for details.)

- Christians have remained fairly stable at the global level in their overall educational attainment over three generations. But their attainment varies considerably by region. As the largest of the world’s major religious groups (numbering about 2.2 billion overall, including children, as of 2010), Christians also are the most widely dispersed faith group, with hundreds of millions of adherents in sub-Saharan Africa, the Asia-Pacific, Europe, North America and Latin America and the Caribbean. Christians in Europe and North America tend to be much more highly educated than those in sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, although African Christians are making rapid educational gains across generations. (See Chapter 2 for more detail on educational attainment among Christians.)

- Jews also have remained stable in their already high levels of educational attainment over recent generations. But Jews, unlike Christians, are a much smaller and more localized population, with a large majority of all Jews worldwide living in just two countries – Israel and the United States – where educational attainment is relatively high overall. (Chapter 6 explores data on Jews in more detail.)

- At the global level, religiously unaffiliated adults have 1.3 more years of schooling, on average, than religiously affiliated adults (8.8 versus 7.5). One possible reason for this is that unaffiliated people are disproportionately concentrated in countries with relatively high overall levels of educational attainment, while the religiously affiliated are more dispersed across countries with both high and low levels of attainment. However, the unaffiliated are not consistently better educated than their religiously affiliated compatriots when looked at country by country. In the 76 countries with data available on the youngest generation of unaffiliated adults (born 1976-1985), they have a similar number of years of schooling as their religiously affiliated peers in 33 countries; they are less educated in 27 countries, and they are more highly educated than the affiliated in 16 countries. (See sidebar in Chapter 3 for more details on the unaffiliated and secularization theory.)

- Hindus in India, who make up a large majority of the country’s population (and more than 90% of the world’s Hindus), have relatively low levels of educational attainment – a nationwide average of 5.5 years of schooling. While they are more highly educated than Muslims in India (14% of the country’s population), they lag behind Christians (2.5% of India’s population). By contrast, fully 87% of Hindus living in North America hold post-secondary degrees – a higher share than any other major religious group in the region. (See Chapter 5 on Hindu educational attainment.)

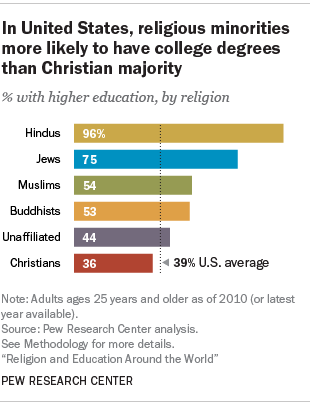

Religious minorities often have more education, on average, than a country’s majority religious group, particularly when the minority group is largely foreign born and comes from a distant country. In these cases, immigrants often were explicitly selected under immigration policies that favor highly skilled applicants. In addition, it is often the well-educated who manage to overcome the financial and logistical challenges faced by those who wish to leave their homeland for a new, far-off country. For instance, in the U.S., where Christians make up the majority of the adult population, Hindus and Muslims are much more likely than Christians to have post-secondary degrees. And unlike Christians, large majorities of Hindus and Muslims were born outside the United States (87% of Hindus and 64% of Muslims compared with 14% of Christians, according to a 2014 Pew Research Center survey). 4

Religious minorities often have more education, on average, than a country’s majority religious group, particularly when the minority group is largely foreign born and comes from a distant country. In these cases, immigrants often were explicitly selected under immigration policies that favor highly skilled applicants. In addition, it is often the well-educated who manage to overcome the financial and logistical challenges faced by those who wish to leave their homeland for a new, far-off country. For instance, in the U.S., where Christians make up the majority of the adult population, Hindus and Muslims are much more likely than Christians to have post-secondary degrees. And unlike Christians, large majorities of Hindus and Muslims were born outside the United States (87% of Hindus and 64% of Muslims compared with 14% of Christians, according to a 2014 Pew Research Center survey). 4

A note about this analysis

This report looks at average educational levels among adherents of five major world religions – Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and Judaism – as well as among the religiously unaffiliated.

Educational systems vary enormously around the world; this report does not attempt to analyze differences in educational quality, but focuses primarily on educational attainment in terms of number of years of schooling. It distinguishes among four broad levels of educational attainment: no formal schooling (less than one year of primary school), primary education (completion of at least one grade of primary school), some secondary education (but no degree beyond high school) and post-secondary education (completion of some kind of college, university or vocational degree beyond high school, also referred to in this report as “higher education”). For comparability across countries, these educational categories are based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED 1997; see Methodology for more details).

To measure changes over recent generations, the report looks at three birth cohorts: the “oldest” (born 1936-1955), “middle” (born 1956-1975) and “youngest” (born 1976-1985). These generations roughly correspond, respectively, to people ages 55 to 74, 35 to 54 and 25 to 34 as of 2010, the most recent year for which detailed census data are available in many countries. Whenever this report refers to “adults,” it means people who were 25 or older in 2010 (or, in some cases, the most recent year for which data are available).

The report presents figures at the global and regional levels but also includes select country-level data as illustrations of larger trends. It includes data from 151 countries, collectively representing 95% of the 3.6 billion people around the world who were 25 or older in 2010. Analyses of change across generations include data from 130 countries with available data on all three birth cohorts, representing 87% of the world’s population in 2010 ages 25 to 74.

The approach in this report is primarily descriptive: It lays out the differences in educational levels among religious groups without attempting to explain the reasons for those differences. Chapter 7 outlines some of the ways that social scientists think religion may influence educational attainment.

In this study, the world is divided into six regions. It includes data from 35 countries in the Asia-Pacific region; 36 countries in Europe, including Russia; 30 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, including Central America and Mexico; 12 countries in the Middle East-North Africa region; Canada and the United States in North America; and 36 countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Fuente: http://www.pewforum.org/2016/12/13/religion-and-education-around-the-world/

Users Today : 3

Users Today : 3 Total Users : 35434562

Total Users : 35434562 Views Today : 4

Views Today : 4 Total views : 3373902

Total views : 3373902