América Latina/08/07/2020/Fuente: Mongabay Latam

El más reciente estudio realizado por la Universidad de Maryland, y publicado por Global Forest Watch, identifica a los diez países con la mayor pérdida de bosques primarios durante 2019. Cinco de estas naciones se encuentran en América Latina.

Entre los datos más impactantes que ofrece este informe es que cada seis segundos se pierde un área de bosques tropicales que equivale a un campo de fútbol. El estudio también destaca que la pérdida de bosques primarios se incrementó en 2.8 % en 2019, si se compara con el año anterior.

En América Latina, la presión sobre los bosques puede incrementarse en los próximos meses, sobre todo a partir de que los gobiernos de la región buscan formas de incentivar la economía ante la crisis provocada por la pandemia del COVID-19.

¿Cuáles fueron las cinco naciones de América Latina que perdieron bosques durante 2019? ¿qué actividades han propiciado el incremento de la deforestación?

1. Brasil: políticas que afectan a los bosques

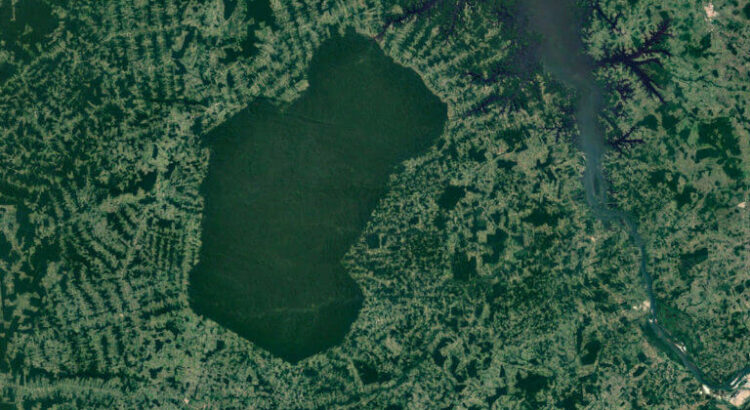

El país sudamericano alberga una de las más importantes superficies de bosques tropicales en el mundo: 60 % de la selva amazónica se encuentra dentro de su territorio. Brasil, es también la nación que registra la deforestación más intensa a nivel mundial: en 2019 perdió un millón 361 mil hectáreas.

El análisis de Global Forest Watch resalta que la pérdida de bosques primarios en Brasil representa un tercio de la cobertura boscosa que dejó de existir en todo el mundo durante 2019. Las principales causas de la intensa deforestación que se vive en Brasil son la expansión de la agricultura, los incendios forestales y la tala selectiva.

Paulo Barreto, investigador asociado del Instituto del Hombre y Medio Ambiente de la Amazonía (Imazon), explica que la la pérdida de bosques ha ido en aumento en los últimos años desde que en 2012 el congreso aprobó una ley que “perdonaba” la deforestación ilegal.

Esta situación se agravó a partir del 1 de enero de 2019, cuando llegó a la presidencia de Brasil Jair Bolsonaro y promovió la aprobación de normas que abren, aún más, la puerta a la minería y a la extracción de petróleo y gas dentro de los territorios indígenas.

El informe de Global Forest Watch resalta que la deforestación se ha acelerado en áreas indígenas de Pará y en territorios de pueblos originarios, donde también ha crecido el acaparamiento de tierras.

2. Bolivia: las cenizas que dejaron los incendios

El fuego tuvo una presencia importante en los bosques de América Latina en 2019. Brasil y Bolivia —este último alberga 6 % de la selva amazónica— fueron dos de los países más afectados por los incendios forestales.

Los incendios fueron, en el caso de Bolivia, una de las causas que contribuyeron a que el país se ubique en el cuarto lugar, a nivel mundial, de naciones con mayor pérdida de bosques primarios durante 2019. El informe de Global Forest Watch resalta que este país sudamericano perdió alrededor de 290 000 hectáreas de bosques primarios. Estudios realizados por la Fundación Amigos de la Naturaleza muestran que, entre 2015 y 2018, Bolivia registró una aceleración de pérdida de bosques que supera las 440 000 hectáreas por año.

Una de las regiones más afectadas por la deforestación en Bolivia es la Chiquitanía, en especial la provincia de Santa Cruz, epicentro de la agricultura a gran escala en el país altoandino. “La agricultura a gran escala es un importante impulsor de la deforestación en Bolivia, particularmente para la soja y la ganadería”, se resalta en el informe del Global Forest Watch.

3. Perú: minería y cultivos ilegales

El 13 % de la selva amazónica se encuentra dentro del territorio del Perú, país que a nivel mundial ocupa el quinto lugar entre las naciones que más bosques primarios perdieron durante 2019.

En ese año, el territorio peruano se quedó sin 162 000 hectáreas de bosques primarios, una cifra que supera en 20 000 hectáreas las cifras de 2018, de acuerdo con datos del Global Forest Wath.

Otro estudio realizado por el Instituto del Bien Común (IBC), basado en imágenes satelitales tomadas entre 2001 y 2015, muestra que durante ese periodo se perdieron 1 932 872 hectáreas, de las cuales 33 708 se encontraban dentro de comunidades nativas tituladas en la Amazonía peruana. Sandra Ríos, investigadora del IBC, destaca que la ilegalidad y la informalidad en la Amazonía son las principales causas de la pérdida de bosques en Perú; así como la minería ilegal y los cultivos ilícitos.

En 2019, Mongabay Latam realizó un recorrido por la zona de Puerto Nuevo, en Ucayali, en el que comprobó que grandes extensiones de bosques han sido invadidas y taladas para sembrar coca de manera ilegal.

4. Colombia: expansión ganadera

En Colombia se encuentra el 79 % de la selva tropical del Chocó (la más húmeda del mundo), así como 8 % de la Amazonía. Y aunque las cifras de la deforestación de bosques primarios han ido a la baja en los últimos años, el país sigue ubicándose entre los diez que más pérdidas registran: en 2019 se ubicó en el séptimo lugar a nivel mundial.

En 2019, de acuerdo con Global Forest Watch, Colombia dejó de tener 115 000 hectáreas de bosques primarios, una cifra que está por debajo de las 157 000 hectáreas que perdió en 2018 y las 128 000 registradas en 2017.

El informe destaca que entre las causas de la pérdida de bosques primarios está el acaparamiento de tierras y la expansión de la ganadería, sobre todo dentro de áreas naturales protegidas.

En junio del 2020, la Fundación para la Conservación y Desarrollo Sostenible en Colombia informó que hasta el 15 de abril se había deforestado más de 75 000 hectáreas de la Amazonía colombiana. Esta organización identificó que en las zonas más deforestadas hay presencia de grupos armados e invasión de territorios indígenas, en donde va en aumento actividades ilegales como el cultivo de coca.

La pérdida de bosques primarios en este país aumentó, sobre todo, a partir de la firma del acuerdo de paz entre el gobierno y las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) en 2016.

5. México: un año crítico

En la lista de países que más bosques primarios perdieron durante 2019, México ocupa el noveno lugar, al presentar una deforestación de 65 000 hectáreas, casi los mismos números que se registraron en países como Laos o Camboya, de acuerdo con los datos de Global Forest Watch.

La pérdida de bosques primarios registrada durante 2019 es la más alta que se ha documentado desde 2001, de acuerdo con los análisis de Global Forest Watch. En 2018, por ejemplo, el país perdió poco más de 45 000 hectáreas de bosques primarios y 55 000 en 2017. Desde 2001 hasta 2019, México ha perdido 602 000 hectáreas de bosques primarios.

El mapa de Global Forest Watch muestra que una de las regiones en donde el país más ha perdido bosques es la Península de Yucatán, territorio en donde se encuentra la selva maya y en donde, en los últimos diez años, se han instalado granjas para la producción cerdos y se ha incrementado la agricultura extensiva. Además, se ha deforestado la selva para instalar campos de generación de energía solar y desarrollos turísticos.

La selva maya forma parte de las selvas tropicales mesoamericanas que, en total, tienen una extensión de 51 millones de hectáreas de cobertura arbórea; incluidos 16 millones de hectáreas de bosque primario.

México es el país que alberga la mayor extensión (39 %) de la cubierta forestal primaria de Mesoamérica, seguido por Guatemala (13 %), Honduras (11 %), Panamá (11 %), Nicaragua (10 %) y Costa Rica (9 %).

Fuente Original : https://es.mongabay.com/2020/07/america-latina-paises-que-perdieron-la-mayor-cantidad-de-bosques-primarios-2019/

Fuente: https://desinformemonos.org/los-cinco-paises-de-america-latina-que-perdieron-la-mayor-cantidad-de-bosques-primarios-en-2019/

Imagen principal: la imagen de Google Earth muestra la deforestación alrededor de Parakanã en el estado de Pará en la Amazonía brasileña.

Users Today : 7

Users Today : 7 Total Users : 35459913

Total Users : 35459913 Views Today : 7

Views Today : 7 Total views : 3418472

Total views : 3418472