Oceania/ Australia/ 15.10.2019/ Source: theconversation.com.

Australia’s refugee policy has led to a two-track education system. Those processed offshore, and deemed refugees by the time they have arrived in Australia, are entitled to fee support for university. But the almost 30,000 boat arrivals, considered illegal entrants, can only access temporary visas. This means a degree has to be paid in full, making it the impossible dream for most.

Policies limiting education follow a political narrative that labels boat arrivals “illegal”. This narrative is difficult to change without widespread community support.

Groups like the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre are training members of the public in how to talk about people who escape harm, rather than debating the legalities of seeking asylum (“It’s not illegal to seek asylum”). These efforts require a range of community leaders, not just stereotypical activists, to rewrite the narrative.

My PhD research on advocacy communications indicated many academics are unsure of how to support people seeking asylum. Advocacy is often seen as an activity for seasoned activists. But like the campaign to get kids off Nauru, led by Australian doctors, academics can play an important role as thought leaders who can influence the hearts and minds of a younger generation.

The right to education

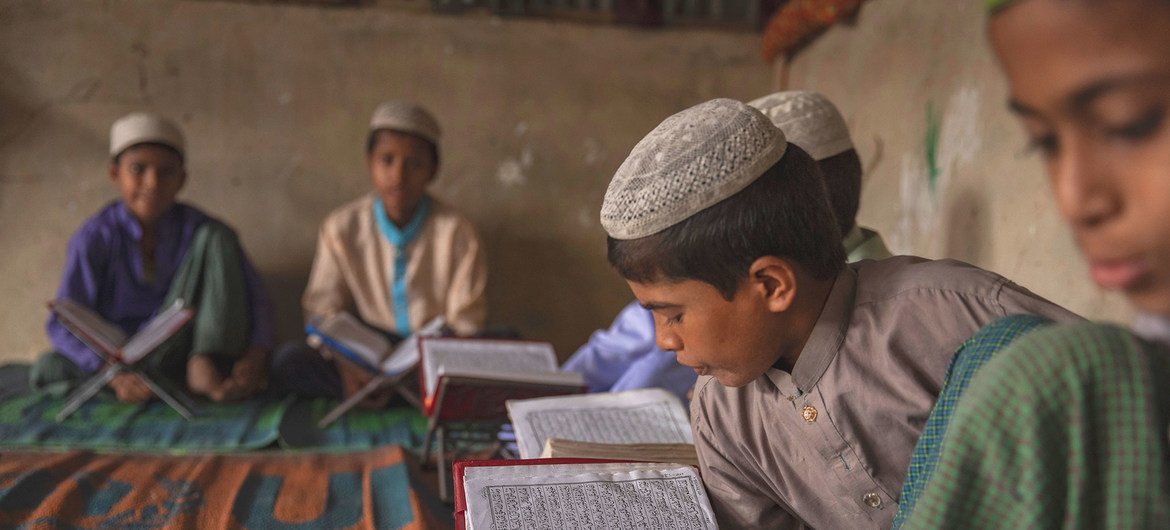

Education is often interrupted for children in conflict situations and when escaping harm such as war or ethnic persecution.

Children who have arrived by boat and sought asylum in Australia will have experienced even longer periods of education disruption in detention centres. In terms of education, these are suitable only as transitory environments, as they lack adequate teaching staff or resources for longer-term schooling.

Australia has no law specifying how long children may be kept in detention. One report estimated this was an average of eight months in 2014, though it can be as long as two to three years.

The Research Council of Australia commissioned research in 2015 to capture the human cost of disrupted and limited education for these children. One Iraqi teen said:

I lost my dad, I lost my brother and I couldn’t stay anymore. I came to be safe here. I came here in 2012. I’m not allowed to work, there are no funds for me to study. When I arrived I was 17. Imagine if you are 17 and you are not allowed to go to school. There are not funds for you to go to school. Now I’m almost 20 […] When can I go to school? When can I go to college? When can I have an education?

An estimated 4,000 children recognised as asylum seekers were in Australian schools in 2015. Under current legislation, they would be denied fee support for university.

Asylum seekers are only entitled to temporary three-to-five-year visas, which require them to pay A$30,000 on average for a degree. This is because Commonwealth-supported degrees are given to citizens or permanent visa holders only.

Improving access to higher education can improve social inclusion and resilience, and help people seeking asylum make a positive contribution to society.

Working migrants are thought to balance an ageing Australian population and shrinking tax base. This is particularly true for recent arrivals from Africa and the Middle East with a high number of children, or second-generation refugees, who will be schooled in Australia.

One study found 80% of these children would be employed in white-collar professions if they earned a bachelor degree or higher. They would also be twice as likely to be employed than if they had only a diploma.

Academics can be activists

Several Australian universities clearly support people seeking asylum. For example, there are 21 full-fee-paying scholarships available to asylum seekers to offset the otherwise impossible costs of a university education.

Other initiatives include Academics for Refugees, with representatives from a number of universities, who want to add their voice to campaign issues. Many academics are using research and teaching to question assumptions and influence students as well as decision-makers.

Academics may not feel confident being advocates, but the potential of a professional voice is clear. #KidsOffNauru was initiated by a group of doctors with access to children in detention. They called on the government to release children on the grounds that long periods of detention were detrimental to their health.

Medics may be unlikely lobbyists, but they added a credible voice on childrens’ physical and mental safety. Advocacy groups credited the campaign with the release of more than 100 children from detention in 2018, though the Australian government claimed it had already been reducing these numbers.

Universities have championed significant improvements for migrants in the past through narratives that challenged dominant political discourse. For example, the 1960s DREAMers movement led to the tabling of the DREAM (Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors) Act. This would have granted legal status to certain undocumented immigrants who were brought to the US as children and went to school there.

These teens had grown up in the US without permanency. They told stories about their American dream and initiated sit-ins and pray-ins across college campuses. The DREAMers campaign transformed the immigration debate in the US, keeping the plight of undocumented migrant youth on the radar.

There are clear parallels between the Australian and US debates around who deserves a permanent visa, with the education rights that come with it. However, an Australian narrative around the ethics of education access is yet to emerge.

Australian academics can help write this narrative through coordinated advocacy and existing research networks, or creative campus initiatives that give a voice to students impacted by immigration policy.

Academics are well placed to shine a spotlight on the human and economic costs of limiting higher education pathways for people seeking asylum.

Source of the notice: http://theconversation.com/asylum-seekers-have-a-right-to-higher-education-and-academics-can-be-powerful-advocates-121753

Users Today : 267

Users Today : 267 Total Users : 35459862

Total Users : 35459862 Views Today : 441

Views Today : 441 Total views : 3418413

Total views : 3418413