Por: Nika Knight

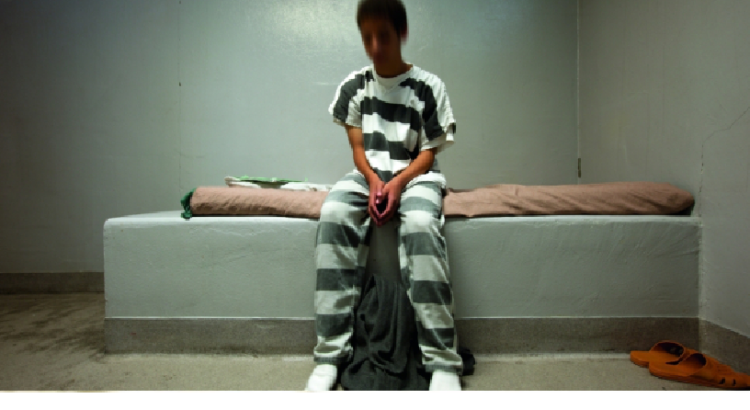

First-of-its-kind report finds children are being imprisoned nationwide when families can’t pay fines levied by juvenile justice system.

Many states are incarcerating poor children whose families can’t afford to pay juvenile court fees and fines, a report published Wednesday finds, which amounts to punishing children for their families’ poverty—and that may be unconstitutional.

Although the growing practice of incarcerating adults who are unable to pay municipal and court fees and fines has been documented for several years, as Common Dreams has noted, the latest report from the Juvenile Law Center is the first in-depth examination of the practice within the juvenile justice system.

The report, “Debtor’s Prison for Kids? The High Cost of Fines and Fees in the Juvenile Justice System” (pdf), documents the results of a survey of 183 people involved in the juvenile justice system—including lawyers, family members, and adults who had been incarcerated as children in the juvenile justice system—in 41 states.

The authors discovered that in most states there is a pile-up of fees and fines imposed on children and their families once a child enters the juvenile justice system, and that “[m]any statutes establish that youth can be incarcerated or otherwise face a loss of liberty when they fail to pay.”

There are myriad ways in which juvenile court systems levy fines on children’s families, the report authors found, and then imprison those children when their families are too poor to pay the mounting costs:

- Many states impose a monthly fee on families whose children are sentenced to probation. When a family can’t pay the monthly fee, that counts as a probation violation, and the child is in most cases incarcerated in a juvenile detention facility.

- If children are sentenced to a “diversion program,” or a community-based program meant to keep them out of detention and help them reintegrate into their communities, the families must pay the costs of such a program. When poor children are unable to pay, they are simply incarcerated instead.

- Families in most states must pay for their children’s court-ordered evaluations and tests (such as mental health evaluations, STD tests, and drug and alcohol assessments). Failure to obtain certain evaluations may result in a failure to be granted bond by the court, which means the child would remain in juvenile detention. Or if the tests are performed and the family subsequently can’t pay for them, that counts as a probation violation and the child is re-sentenced, which can mean being incarcerated.

- Some sentences involve a simple fine, such as truancy, and failure to pay results in the child’s imprisonment. “Even when fines are not mandated by statute, they may be treated as mandatory in practice,” the report authers note, describing one impoverished child’s experience with a $500 truancy fine in Arkansas:

One individual who had been in the juvenile justice system there reported that he spent three months in a locked facility at age 13 because he couldn’t afford the truancy fine. He appeared in court without a lawyer or a parent and was never asked about his capacity to pay or given the option of paying a reduced amount. He assumed he had to either pay the full fine or spend time in jail. He explained, “my mind was set to where I was just like forget it, I might as well just go ahead and do the time because I ain’t got no money and I know the [financial] situation my mom is in. I ain’t got no money so I might as well just go and sit it out.”

- “Almost all states charge parents for the care and support of youth involved with the juvenile justice system,” the report adds. Those include fees for room and board, clothing, and mental and physical healthcare, among many other charges, and “[i]nability to pay […] can result in youth being deprived of treatment, held in violation of probation, or even facing extended periods of incarceration.” (Juvenile prisons also charge their own, often higher, prices for children’s prescription medications, the report says, which frequently results in high charges that poor families cannot afford to pay and interrupts necessary healthcare for their children.)

- In all 50 states, a statute exists which deems that if a child and their family can’t afford restitution charges—that is, payment to the victim(s) of the child’s crime, which is a popular sentence in juvenile court—the child is incarcerated.

In addition, juvenile detention facilities are often unsafe and inhumane, as CommonDreams has reported.

And the fines imposed by juvenile court are “highly burdensome,” according to the Juvenile Law Center report. The average cost of juvenile system involvement is $2,000 per case in Alameda County, California, for example, and “[f]or young people incarcerated for extended periods of time, the costs can be significantly higher.”

The debt divides families already struggling with the ramifications of poverty, the report notes.

“The debt in effect creates a rift between parents and their children,” one survey respondent said, recalling that “I… spoke to a family where a grandmother had taken custody of her grandson but when facing these insurmountable fees, she was told (by a county employee) that the only way she could avoid paying was to hand over custody. Given her limited income, she has seriously considered giving up custody of her grandson, which would make him a ward of the state…”

In some cases, parents can even face imprisonment themselves if they fail to pay their children’s juvenile court system fees. “In a number of states, parents, like youth, may be found in contempt, either civil or criminal, for failure to pay,” the report says.

“Parents may also face increased financial liability through collection fees and interest accruing on payments, as well as civil judgments for failure to pay,” the report authors add. “When parents face incarceration or mounting debt for failure to pay, they have even fewer resources to devote to educating, helping, and supporting their children.”

The authors of the report also observe that incarcerating children for their families’ inability to pay fees may be unconstitutional:

[I]t is worth noting that the United States Supreme Court has made clear that an individual may not be incarcerated for nonpayment if the court does not first conduct an indigence determination and establish that the failure to pay was willful. The Supreme Court has also held that courts must consider “alternative measures of punishment other than imprisonment” for indigent defendants. Nonetheless, some states require neither willfulness nor capacity to pay in statute, and only a few explicitly limit or prohibit incarceration for failure to pay. Additionally, the Supreme Court has held that “courts must provide meaningful notice and, in appropriate cases, counsel, when enforcing fines and fees.” This right is even more important for children, who lack both the developmental capacity and the legal knowledge to represent themselves.

“Moreover,” the report continues, “while further research is needed, existing studies suggest that court costs, fees, and fines have limited, if any, fiscal benefit to states and counties, given the difficulty in collecting from families in poverty and the high administrative costs in trying to do so.”

The Juvenile Law Center details the varying policies on juvenile court system fees state-by-state on a new website, and also highlights the few counties and states who are attempting to rectify the problem.

“Ultimately, state and local policymakers should establish more sustainable and effective models for funding court systems rather than imposing costs on youth and families who simply can’t afford to pay,” the Juvenile Law Center says.

—

First published in CommonDreams. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 License.

Fuente: https://voxpopulisphere.com/2016/09/05/nika-knight-debtors-prison-for-kids-poor-children-incarcerated-when-families-cant-pay-juvenile-court-fees/comment-page-1/

Users Today : 6

Users Today : 6 Total Users : 35460137

Total Users : 35460137 Views Today : 10

Views Today : 10 Total views : 3418793

Total views : 3418793