It’s time to accept that the pandemic has changed the way we exist forever. Now the human race has to embark on the profoundly difficult and painful process of deciding what form the ‘new normality’ is going to take.

The world has lived with the pandemic for most of 2020, but what is our situation with regard to it now, in early December, in the middle of what the European media is terming ‘the second wave’? Firstly, we should not forget that the distinction between the first and second wave is centred on Europe: in Latin America the virus followed a different path. The peak was reached in between the two European waves, and now, as Europe suffers the second of these, the situation in Latin America has marginally improved.

We should also bear in mind the variations in how the pandemic affects different classes (the poor have been hit more badly), different races (in the US, the blacks and Latinos suffer much more) and the different sexes.

And we should be especially mindful of countries where the situation is so bad – because of war, poverty, hunger and violence – that the pandemic is considered one of the minor evils. Consider, for example, Yemen. As the Guardian reported, “In a country stalked by disease, Covid barely registers. War, hunger and devastating aid cuts have made the plight of Yemenis almost unbearable.” Similarly, when the short war erupted between Azerbaijan and Armenia, Covid clearly became less of a priority. However, in spite of these complications, there are some generalisations we can make when comparing the second wave with the peak of the first wave.

What we have discovered about the virus

For a start, some hopes have been dashed. Herd immunity doesn’t appear to work. And deaths are at a record level in Europe, so the hope that we have a milder variation of the virus even though it is spreading more than ever doesn’t hold.

We are also dealing with many unknowns, especially about how the virus is spreading. In some countries, this impenetrability has given birth to a desperate search for guilty parties, such as private home gatherings and work places. The oft-heard phrase that we have to ‘learn to live with the virus’ just expresses our capitulation to it.

While vaccines bring hope, we should not expect they will magically bring an end to all our troubles and the old normality will return. Distribution of the vaccines will be our biggest ethical test: will the principle of universal distribution that covers all of humanity survive, or will it be diluted through opportunist compromises?

It’s also obvious that the limitations of the model which many countries are following – that of striking a balance between fighting the pandemic and keeping the economy alive – are increasingly being demonstrated. The only thing that appears to really work is radical lockdown. Take, for example, the state of Victoria in Australia: in August it had 700 new cases per day, but in late November, Bloomberg reported that it “has gone 28 days with no new cases of the virus, an enviable record as the US and many European countries grapple with surging infections or renewed lockdowns.”

And with regard to mental health, we can now say, in retrospect, that the reaction of people at the peak of the first wave was a normal and healthy response when faced with a threat: their focus was on avoiding infection. It was as if most of them simply didn’t have time for mental problems. Although there is much talk today about mental problems, the predominant way people relate to the epidemic is a strange mix of disparate elements. In spite of the rising number of infections, in most countries the pandemic is still not taken too seriously. In some strange sense, ‘life goes on’. In Western Europe, many people are more concerned if they will be able to celebrate Christmas and do the shopping, or if they will be able to take their usual winter holidays.

Transitioning from fear to depression

However, this ‘life goes on’ stance – indications that we have somehow learned to live with the virus – is quite the opposite of relaxation because the worst is over. It is inextricably mixed with despair, violations of state regulations and protests against them. Since there is no clear perspective offered, there is something deeper than fear at work: we have passed from fear to depression. We feel fear when there is a clear threat, and we feel frustration when obstacles emerge again and again which prevent us from reaching what we strive for. But depression signals that our desire itself is vanishing.

What causes such a sense of disorientation is that the clear order of causality appears to us as perturbed. In Europe, for reasons which remain unclear, the numbers of infections are now falling in France and rising in Germany. Without anyone knowing exactly why, countries which were a couple of months ago held as models of how to deal with the pandemic are now its worst victims. Scientists play with different hypotheses, and this very disunity strengthens a sense of confusion and contributes to a mental crisis.

What further strengthens this disorientation is the mixture of different levels that characterises the pandemic. Christian Drosten, the leading German virologist, pointed out that the pandemic is not just a scientific or health phenomenon, but a natural catastrophe. One should add to this that it is also a social, economic and ideological phenomenon: its actual effect incorporates all these elements.

For example, CNN reports that in Japan, more people died from suicide in October than from Covid during the entirety of 2020, and women were impacted most. But the majority of individuals committed suicide because of the predicament they found themselves in because of the pandemic, so their deaths are collateral damage.

There is also the impact the pandemic is having on the economy. In the Western Balkans, hospitals are pushed over the edge. As a doctor from Bosnia said, “One of us can do the work of three (people), but not of five.” As France24 reported, one cannot understand this crisis without reflecting on the “brain drain crisis, with an exodus of promising young doctors and nurses leaving to seek better wages and training abroad.” So, again, the catastrophic impact of the pandemic is clearly caused also by the emigration of the workforce.

Accepting the disappearance of our social life

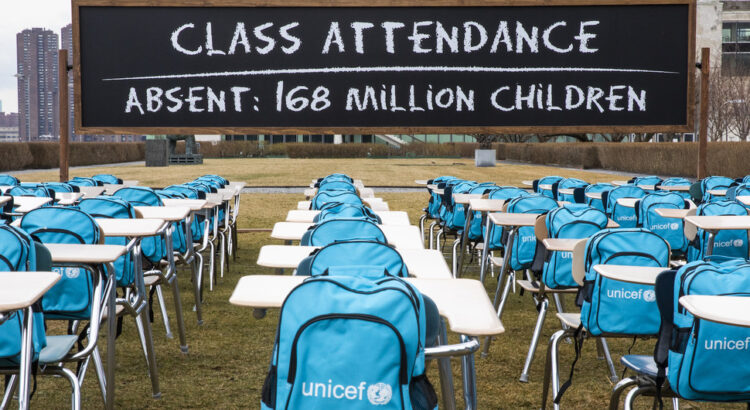

We can therefore safely conclude that one thing is sure: if the pandemic really does proceed in three waves, the general character of each wave will be different. The first wave understandably focused our attention on the health issues, on how to prevent the virus from expanding to an intolerable level. That’s why most countries accepted quarantines, social distancing etc. Although the numbers of infected are much higher in the second wave, the fear of long-term economic consequences is nonetheless growing. And if the vaccines will not prevent the third wave, one can be sure that its focus will be on mental health, on the devastating consequences of the disappearance of what we perceive as normal social life. This is why, even if the vaccines work, mental crises will persist.

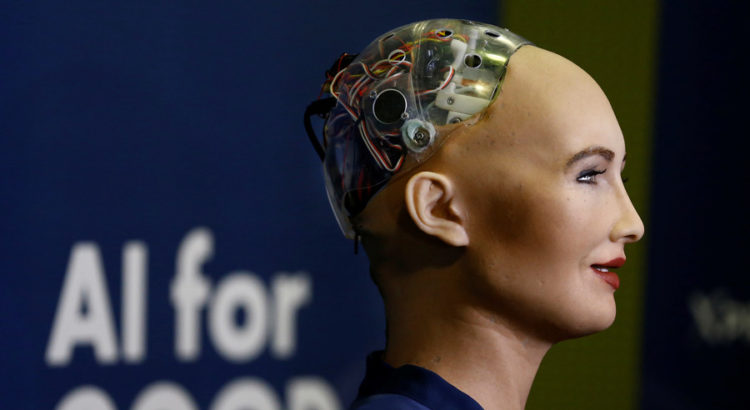

The ultimate question we are facing is this: Should we strive for a return to our ‘old’ normality? Or should we accept that the pandemic is one of the signs that we are entering a new ‘post-human’ era (‘post-human’ with regard to our predominant sense of what being human means)? This is clearly not just a choice that concerns our psychic life. It is a choice that is in some sense ‘ontological’, it concerns our entire relation to what we experience as reality.

The conflicts over how best to deal with the pandemic are not conflicts between different medical opinions; they are serious existential ones. Here is how Brenden Dilley, a Texas chat-show host, explained why he is not wearing a mask: “Better to be dead than a dork. Yes, I mean that literally. I’d rather die than look like an idiot right now.” Dilley refuses to wear a mask since, for him, walking around with a mask is incompatible with human dignity at its most basic level.

What is at stake is our basic stance towards human life. Are we – like Dilley – libertarians who reject any encroaching upon our individual freedoms? Are we utilitarians ready to sacrifice thousands of lives for the economic wellbeing of the majority? Are we authoritarians who believe that only a tight state control and regulation can save us? Are we New Age spiritualists who think the epidemic is a warning from nature, a punishment for our exploitation of natural resources? Do we trust that God is just testing us and will ultimately help us to find a way out? Each of these stances relies on a specific vision of what humans are. It concerns the level at which we are, in some sense, all philosophers.

Taking all this into account, Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben claims that if we accept the measures against the pandemic, we thereby abandon open social space as the core of our being human and turn into isolated survival machines controlled by science and technology, serving the state administration. So even when our house is on fire, we should gather the courage to go on with life as normal and eventually die with dignity. He writes: “Nothing I’m doing makes any sense if the house is on fire. Yet even when the house is on fire it is necessary to continue as before, to do everything with care and precision, perhaps even more so than before – even if no one notices. Perhaps life itself will disappear from the face of the earth, perhaps no memory whatsoever will remain of what has been done, for better or for worse. But you continue as before, it is too late to change, there is no time anymore.”

One should note an ambiguity in Agamben’s line of argumentation: is “the house on fire” due to the pandemic, global warming etc? Or is our house on fire because of the way we (over)reacted to the reality of the pandemic? “Today the flame has changed its form and nature, it has become digital, invisible and cold – but precisely for this very reason it is even closer still and surrounds us at every moment.” These lines clearly sound Heideggerian: they locate the basic danger in how the pandemic strengthened the way medical science and digital control regulate our reaction to it.

Why we cannot maintain our old way of life

Does this mean that, if we oppose Agamben, we should resign ourselves to the loss of humanity and forget the social freedoms we were used to? Even if we ignore the fact that these freedoms were actually much more limited than it may appear, the paradox is that only by way of passing through the zero point of this disappearance can we keep the space open for the new freedoms-to-come.

If we stick to our old way of life, we will for sure end in new barbarism. In the US and Europe, the new barbarians are precisely those who violently protest against anti-pandemic measures on behalf of personal freedom and dignity – those like Jared Kushner, Donald Trump’s son-in- law, who, back in April, bragged that Trump was taking the country “back from the doctors” – in short, back from those who only can help us.

However, one should note that in the very last paragraph of his text, Agamben leaves open the possibility that a new form of post-human spirituality will emerge. “Today humankind is disappearing, like a face drawn in the sand and washed away by the waves. But what is taking its place no longer has a world; it is merely a bare and muted life without history, at the mercy of the computations of power and science. Perhaps, however, it is only by beginning from this wreckage that something else can appear, whether slowly or abruptly – certainly not a god, but not another man either – a new animal perhaps, a soul that lives in some other way…”

Agamben alludes here to famous lines from Foucault’s Les mot et les choses when he refers to humankind disappearing like a figure drawn on sand being erased by waves on a shore. We are effectively entering what can be called a post-human era. The pandemic, global warming and the digitalisation of our lives – including direct digital access to our psychic life – corrode the basic coordinates of our being human.

So how can (post-)humanity be reinvented? Here is a hint. In his opposition to wearing protective masks, Giorgio Agamben refers to French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas and his claim that the face “speaks to me and thereby invites me to a relation incommensurate with a power exercised.” The face is the part of another’s body through which the abyss of the Other’s imponderable Otherness transpires.

Agamben’s obvious conclusion is that, by rendering the face invisible, the protective mask renders invisible the invisible abyss itself which is echoed by a human face. Really?

There is a clear Freudian answer to this claim: Freud knew well why, in an analytical session – when it gets serious, i.e. after the so-called preliminary encounters – the patient and the analyst are not confronting each other face to face. The face is at its most basic a lie, the ultimate mask, and the analyst only accedes to the abyss of the Other by NOT seeing its face.

Accepting the challenge of post-humanity is our only hope. Instead of dreaming about a ‘return to (old) normality’ we should engage in a difficult and painful process of constructing a new normality. This construction is not a medical or economic problem, it is a profoundly political one: we are compelled to invent a new form of our entire social life.

Source and Image: https://www.rt.com/op-ed/508940-normality-covid-pandemic-return/

Users Today : 22

Users Today : 22 Total Users : 35459488

Total Users : 35459488 Views Today : 28

Views Today : 28 Total views : 3417786

Total views : 3417786