Europa/Inglaterra/ economist.com

Resumen: En 2015, Sir James Dyson, inventor y empresario, atacó a Theresa May, entonces secretaria de familia, sobre sus planes de hacer más difícil que los estudiantes extranjeros permanezcan en Gran Bretaña después de terminar sus estudios. Después de todo, las «últimas encuestas» mostraban que decenas de miles estudiantes llegaban más en comparación de los que salían cada año. La implicación: Gran Bretaña tenía ya bastantes graduados extranjeros que se mantienen alrededor. Ahora está claro que el argumento de la Sra. May era absurdo. Sus números provienen de la encuesta internacional de pasajeros, una encuesta realizada hace medio siglo para medir el turismo. El 24 de agosto surgió que el número de estudiantes que excedían ilegalmente sus visas era una pequeña fracción de las estimaciones anteriores. Las cifras de la Oficina de Estadísticas Nacionales han sugerido que podría haber habido más de 90.000 excedentes por año. Los nuevos datos mostraron que había un máximo de 4.617 en 2016-17.

That error led to a needless, costly crackdown on universities

IN 2015 Sir James Dyson, an inventor and businessman, attacked Theresa May, then home secretary, over her plans to make it harder for foreign students to stay in Britain after finishing their studies. “Train ’em up. Kick ’em out. It’s a bit shortsighted, isn’t it?” he wrote. Not so, replied Mrs May. After all, the “latest surveys” showed that tens of thousands more students arrived than left each year. The implication: Britain already had more than enough foreign graduates hanging around.

It is now clear that Mrs May’s argument was nonsense. Her numbers came from the International Passenger Survey, a poll introduced half a century ago to measure tourism. On August 24th it emerged that the number of students illegally overstaying their visas was a small fraction of previous estimates. Figures from the Office for National Statistics had suggested there could have been more than 90,000 overstayers per year. New data showed that there were at most 4,617 in 2016-17.

Some have questioned why it took so long for the information to come out. One former Downing Street official admits to having been briefed on an earlier version of the data in autumn 2015. Universities have nevertheless welcomed the release, grateful for a new way to make the case for international students. They have not had much luck in recent years. During Mrs May’s time at the Home Office she introduced a range of policies to deter foreign students, often justified by the number overstaying their visas.

Perhaps most damagingly, in 2012 the government scrapped a visa that allowed graduates to remain in the country for two years without a job offer. Other changes include stricter limits on bringing over family members, making it harder to move from one type of study to another, tougher language requirements and uncompromising “credibility interviews”.

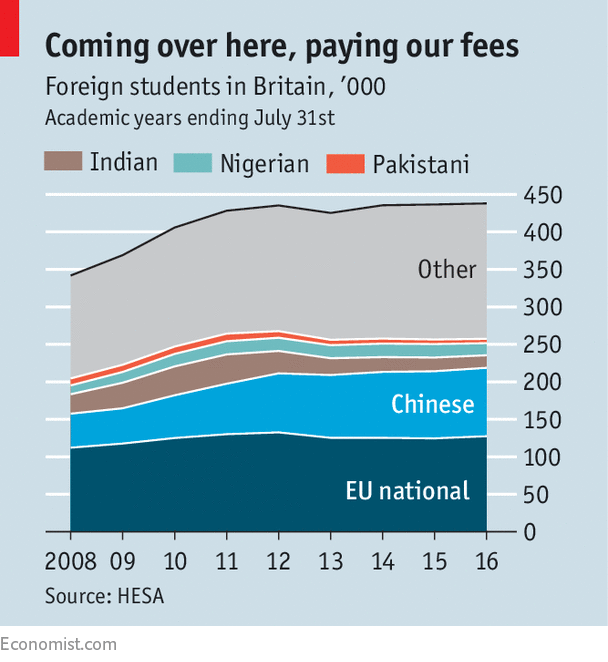

While Britain was making life harder for foreign students, other countries wooed them. As a result, British institutions now have a smaller share of a larger market. International student numbers have continued to rise at Britain’s top universities, but the rest have found recruitment difficult. The number coming from India and Pakistan has more than halved since 2011, and although a big rise in Chinese students has made up the difference, growth has been slower than in America.

The economy has suffered as a result. The Department for Education found that higher-education exports were worth £12.4bn ($20.6bn) in 2014. In 2000-10 the number of foreign students at British universities almost doubled, helping to finance a big expansion in education for home students. Whereas students from Britain and other EU countries have their fees limited to £9,250 a year, no such cap exists for the rest.

Other benefits are harder to measure. According to the Higher Education Policy Institute, more heads of state and government have been educated in Britain than anywhere else. Benazir Bhutto, a future prime minister of Pakistan, introduced Mrs May to her husband at Oxford.

Liberals in the cabinet may now be gaining the upper hand. The government has dropped plans to link visa conditions to the quality of education provided by universities. Amber Rudd, the home secretary, has commissioned the official Migration Advisory Committee to analyse the economic impact of foreign students and is expected to push for softer rules.

One change would be to remove students from the government’s target to limit net migration to under 100,000 a year. Another would be to extend the time graduates are allowed to spend hunting for a job in Britain. Either would be welcome. But a more sensible government would look at how to recruit more foreign students, not just refrain from turning them away.

Users Today : 88

Users Today : 88 Total Users : 35459554

Total Users : 35459554 Views Today : 138

Views Today : 138 Total views : 3417896

Total views : 3417896