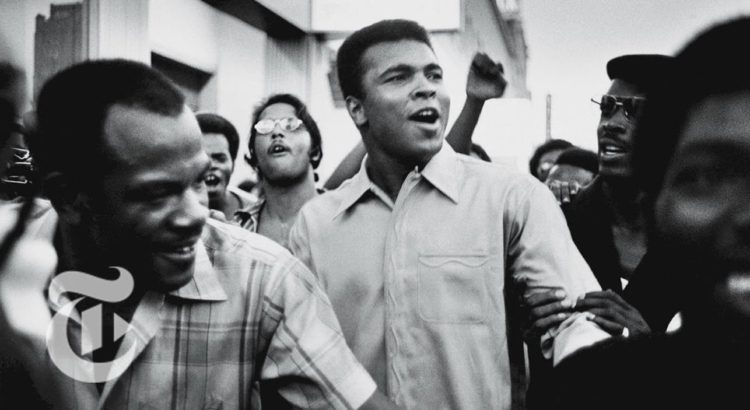

My heart is broken over the death of Muhammad Ali, who was a hero for those of us raised in the sixties and for whom he modeled that poetic dialectic between the body and a notion of resistance. For my working class generation, the body was all we had–a site of danger, hope, possibility, confusion, and dread–he elevated that understanding into the political realm by mediating those working class concerns into a brave and courageous understanding of politics as a site of resistance. He made it clear that resistance was a poetic act that was continually being written. He unsettled the racial order, protested the war, and danced in the ring like a butterfly–a master of wit, performance, and sheer courage. But outside of being the greatest boxer in the world, he sacrificed three and a half years of his career for the ideals in which he believed. He was not merely an icon of history, he helped to shape it. Ali had his flaws and his ridicule of Joe Frazier and his disowning of Malcolm X speak to those shortcomings, but Ali was not a god, he was simply flawed differently. It will be hard to find people like Ali in the future now that self interest and a pathological narcissism has taken over the culture in the age of casino capitalism. I will miss him and only hope his legacy will leave the traces of resistance that will inspire another generation. He was a champ in the most courageous sense who showed generations of working class kids how to talk back with dignity and grace.

Author: Henry Giroux

Confronting entertainment as anti-politics

What liberals forget is that elections no longer matter, because they are rigged. Moreover, changing governments results in very little change when it comes to the concentration of class power and the decimation of the commons and public good. At the same time, politicians in the age of Reality TV embody Neil Postman’s statement that cosmetics has replaced ideology and has helped to usher in the age of anti-politics. Power hides in the dictates of common sense and wields destruction and misery through the «innocent criminals» that produce austerity polices and delight in a global social order dominated by precarity, fear, anxiety, and isolation. What happens when politics turns into burlesque, when entertainment washes out all that matters, when violence espouses not simply the spectacle, but reaches for the threshold of the intolerable? What happens to a society when baby talk replaces thoughtful dialogue, infantilism becomes the modus operandi of news casters, and trivia becomes the only acceptable mode of narration? What happens when compassion is treated as a pathology and the culture of cruelty becomes a source of humor and an object of veneration? What happens to a democracy when it has lost all semblance of public memory and the welfare state and social contract are abandoned in order to fill the coffers of bankers, hedge fund managers, and the corporate elite?As Colin Crouch asked: How much capitalism can a democracy endure? What language and public spheres do we need to make hope realistic and a new politics possible?

Taking notes 60: why teachers matter in dark times

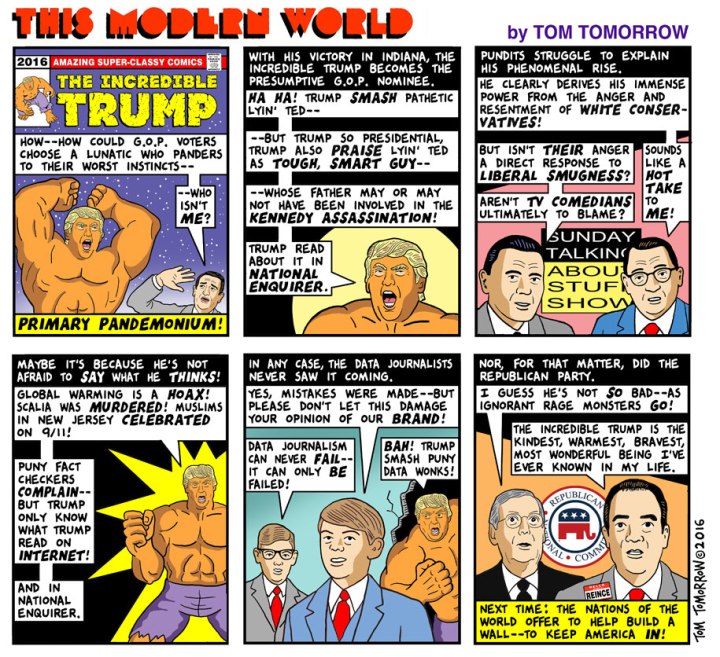

Americans live in a historical moment that annihilates thought. Ignorance now provides a sense of community; the brain has migrated to the dark pit of the spectacle; the only discourse that matters is about business; poverty is now viewed as a technical problem; thought chases after an emotion that can obliterate it. The presumptive Republican Party presidential nominee, Donald Trump, declares he likes “the uneducated” — implying that it is better that they stay ignorant than be critically engaged agents — and boasts that he doesn’t read books. Fox News offers no apologies for suggesting that thinking is an act of stupidity.

A culture of cruelty and a survival-of-the-fittest ethos in the United States is the new norm and one consequence is that democracy in the United States is on the verge of disappearing or has already disappeared! Where are the agents of democracy and the public spaces that offer hope in such dark times? Many are in public schools — all the more reason to praise public school teachers and to defend public and higher education as a public good.

For the most part, public school teachers and higher education faculty are a national treasure and may be one of the last defenses available to undermine a growing authoritarianism, pervasive racism, permanent war culture, widening inequality and debased notion of citizenship in US society. They can’t solve these problems but they can educate a generation of students to address them. Yet, public school teachers, in particular, are underpaid and overworked, and lack adequate resources. In the end, they are unjustly blamed by right-wing billionaires and politicians for the plight of public schools. In order to ensure their failure, schools in many cities, such as Detroit and Philadelphia, have been defunded by right-wing legislators. These schools are dilapidated — filled with vermin and broken floors — and they often lack heat and the most basic resources. They represent the mirror image of the culture of cruelty and dispossession produced by the violence of neoliberalism.

![[Credit: Taylor/Daily call.org.]](https://philoforchange.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/naz_trump.jpg?w=720&h=498)

call.org.]

Under the counterfeit appeal to reform, national legislation imposes drill-and-test modes of pedagogy on teachers that kill the imagination of students. Young people suffer under the tyranny of methods that are forms of disciplinary repression. Teachers remain powerless as administrators model their schools after prisons and turn students over to the police. And in the midst of such egregious assaults, teachers are disparaged as public servants.

The insecure, overworked adjunct lecturers employed en masse at most institutions of higher education fare no better. They have been reduced to an army of indentured wage slaves, with little or no power, benefits or time to do their research. Some states, such as Texas, appear to regard higher education as a potential war zone and have passed legislation allowing students to carry concealed weapons on campus. That is certainly one way to convince faculty not to engage in controversial subjects with their students. With the exception of the elite schools, which have their own criminogenic environments to deal with, higher education is in free fall, undermined as a democratic public sphere and increasingly modeled after corporations and run by armies of administrators who long to be called CEOs.

All the while the federal government uses billions of dollars to fuel one of the largest defense and intelligence budgets in the world. The death machine is overflowing with money while the public sector, social provisions and public goods are disappearing. At the same time, many states allocate more funds for prisons than for higher education. Young children all over the country are drinking water poisoned with lead, while corporations rake in huge profits, receive huge tax benefits, buy off politicians and utterly corrupt the political system. Trust and compassion are considered a weakness if not a liability in an age of massive inequities in wealth and power.

![[Credit: Stephanie Mcmillan.]](https://philoforchange.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/teach_stephanie_mcmillan.jpg?w=720)

In the midst of what can only be viewed as a blow against democracy, right-wing Republicans produce slash-and-burn policies that translate into poisonous austerity measures for public schools and higher education. As Jane Mayer points out in Dark Money, the Koch brothers and their billionaire allies want to abolish the minimum wage, privatize schools, eliminate the welfare state, pollute the planet at will, break unions and promote policies that result in the needless deaths of millions who lack adequate health care, jobs and other essentials. Public goods such as schools, according to these politicians and corporate lobbyists, are financial investments, viewed as business opportunities. For the billionaires who are the anti-reformers, teachers, students and unions simply get in the way and must be disciplined.

Public schools and higher education are “dangerous” because they hold the potential to serve as laboratories for democracy where students learn to think critically. Teachers are threatening because they refuse to conflate education with training or treat schools as if they were car dealerships. Many educators have made it clear that they regard teaching for the test and defining accountability only in numerical terms as acts that dull the mind and kill the spirit of students. Such repressive requirements undermine the ability of teachers to be creative, engage with the communities in which they work and teach in order to make knowledge critical and transformative. The claim that we have too many bad teachers is too often a ruse to hide bad policies and to unleash assaults on public schools by corporate-driven ideologues and hedge fund managers who view schools strictly as investment opportunities for big profits.

We need to praise teachers, hold them to high standards, pay them the salaries they deserve, give them control over their classrooms, reduce class sizes and invest as much, if not more, in education as we do in the military-industrial complex. This is all the more reason to celebrate and call attention to those teachers in Chicago, Detroit and Seattle who are collectively fighting against such attacks on public schools. We need to praise them, learn from them and organize with them because they refuse to treat education as a commodity and they recognize that the crisis of schooling is about the crises of democracy, economic equality and justice. This is not a minor struggle because no democracy can survive without informed citizens.

![[Credit: Judy Green.]](https://philoforchange.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/teach_judy-green.jpg?w=720)

Neoliberal education is increasingly expressed in terms of austerity measures and market-driven ideologies that undermine any notion of the imagination, reduce faculty to an army of indentured labor and burden students with either a mind-numbing education or enormous crippling debt or both. If faculty and students do not resist this assault, they will no longer have any control over the conditions of their labor, and the institutions of public and higher education will further degenerate into a crude adjunct of the corporation and financial elite.

Clearly, it is time to revisit Mario Savio’s famous speech at Berkeley in 1964 when he called for shutting down an educational system that had become odious. In his own words:

There comes a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part, you can’t even passively take part; and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, the people who own it, that unless you’re free the machine will be prevented from working at all.

Savio’s call to resistance is more relevant today than it was then. Public schools not only mimic the injustices of an oppressive economic system, but also funnel poor youth of color into the criminal legal system. The good news is that there is an echo of outrage and resistance now emerging in the United States, especially among young people such as those in the Black Lives Matter movement.

If the major index of any democracy is measured by how a society treats its children, the United States is failing. Fortunately, more and more people are waking up and realizing that the fight for public schooling is not just about higher salaries for teachers; it is about investing in our children and in democracy itself. At the same time, we live in what author Carl Boggs and others have called a permanent warfare state, one in which every space appears to be a battlefield, and the most vulnerable are viewed not only as an imminent threat, but also as the object of potential violence. This suggests that the battle of education must become part of a wider political struggle. This is a struggle that connects assaults on education with the broader war on youth, police violence with the militarization of society and specific instances of racist brutality with the unchecked exercise of the systemic power of finance capital. But the struggle will not be easy.

Beneath all of the current brutality, racism and economic predation, there is some hope inspired by the generation of young people who are protesting police violence and the attack on public and higher education and working hard to invent a politics that gets to the root of issues. There is also a glimmer of possibility in those youth who have supported Bernie Sanders but are really demanding a new and more radical definition of politics: Their vision far surpasses that of the left-centrists and liberals of the Democratic Party.

Elections are the ruse of capitalism, and that has never been more clear than at the present moment. On the one side we have Hillary Clinton, a warmonger, a strong supporter of the financial elite and a representative of a neoliberalism that is as brutal as it is cruel. On the other side we have Donald Trump, a circus barker inviting Americans into a den of horrors. And these are the choices that constitute democracy? I don’t think so.

Collective self-delusion will only go so far in the absence of an education system that offers a space for critical learning and dissent, and functions as a laboratory for democracy. There is a tendency to forget in an age dominated by the neoliberal celebration of self-interest and unchecked individualism that public goods matter, that critical thinking is essential to an informed public and that education at the very least should provide students with unsettling ruptures that display the fierce energy of outrage and the hope for a better world.

But a critical education has the capacity to do more. It also has the power not only to prevent justice from going dead in ourselves and the larger society, but also, in George Yancy’s poetic terms, to teach us how to “love with courage.” Hopefully, while education cannot solve such problems, it can produce the formative cultures necessary to enable a generation of young people to create a robust third party — a party fueled by social movements demanding the economic and political justice that could allow a radical democracy to come to life.

![[Credit: indybay.org.]](https://philoforchange.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/obama-indybay-org.jpg?w=720)

[Thank you Henry for this piece. The article first appeared onTruthout.org.]

The writer is McMaster University Professor for Scholarship in the Public Interest in the English and Cultural Studies Department and the Paulo Freire Chair in Critical Pedagogy at The McMaster Institute for Innovation & Excellence in Teaching & Learning. He is also a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Ryerson University. His web site ishttp://www.henryagiroux.com and his other site is MCSPI.

Why Teachers Matter in Dark Times

Americans live in a historical moment that annihilates thought. Ignorance now provides a sense of community; the brain has migrated to the dark pit of the spectacle; the only discourse that matters is about business; poverty is now viewed as a technical problem; thought chases after an emotion that can obliterate it. The presumptive Republican Party presidential nominee, Donald Trump, declares he likes «the uneducated» — implying that it is better that they stay ignorant than be critically engaged agents — and boasts that he doesn’t read books. Fox News offers no apologies for suggesting that thinking is an act of stupidity.

A culture of cruelty and a survival-of-the-fittest ethos in the United States is the new norm and one consequence is that democracy in the United States is on the verge of disappearing or has already disappeared! Where are the agents of democracy and the public spaces that offer hope in such dark times? Many are in public schools — all the more reason to praise public school teachers and to defend public and higher education as a public good.

Public schools and higher education are «dangerous» because they hold the potential to serve as laboratories for democracy.

For the most part, public school teachers and higher education faculty are a national treasure and may be one of the last defenses available to undermine a growing authoritarianism, pervasive racism, permanent war culture, widening inequality and debased notion of citizenship in US society. They can’t solve these problems but they can educate a generation of students to address them. Yet, public school teachers, in particular, are underpaid and overworked, and lack adequate resources. In the end, they are unjustly blamed by right-wing billionaires and politicians for the plight of public schools. In order to ensure their failure, schools in many cities, such as Detroit and Philadelphia, have been defunded by right-wing legislators. These schools are dilapidated — filled with vermin and broken floors — and they often lack heat and the most basic resources. They represent the mirror image of the culture of cruelty and dispossession produced by the violence of neoliberalism.

Under the counterfeit appeal to reform, national legislation imposes drill-and-test modes of pedagogy on teachers that kill the imagination of students. Young people suffer under the tyranny of methods that are forms of disciplinary repression. Teachers remain powerless as administrators model their schools after prisons and turn students over to the police. And in the midst of such egregious assaults, teachers are disparaged as public servants.

The insecure, overworked adjunct lecturers employed en masse at most institutions of higher education fare no better. They have been reduced to an army of indentured wage slaves, with little or no power, benefits or time to do their research. Some states, such as Texas, appear to regard higher education as a potential war zone and have passed legislation allowing students to carry concealed weapons on campus. That is certainly one way to convince faculty not to engage in controversial subjects with their students. With the exception of the elite schools, which have their own criminogenic environments to deal with, higher education is in free fall, undermined as a democratic public sphere and increasingly modeled after corporations and run by armies of administrators who long to be called CEOs.

All the while the federal government uses billions of dollars to fuel one of the largest defense and intelligence budgets in the world. The death machine is overflowing with money while the public sector, social provisions and public goods are disappearing. At the same time, many states allocate more funds for prisons than for higher education. Young children all over the country are drinking water poisoned with lead, while corporations rake in huge profits, receive huge tax benefits, buy off politicians and utterly corrupt the political system. Trust and compassion are considered a weakness if not a liability in an age of massive inequities in wealth and power.

In the midst of what can only be viewed as a blow against democracy, right-wing Republicans produce slash-and-burn policies that translate into poisonous austerity measures for public schools and higher education. As Jane Mayer points out in Dark Money, the Koch brothers and their billionaire allies want to abolish the minimum wage, privatize schools, eliminate the welfare state, pollute the planet at will, break unions and promote policies that result in the needless deaths of millions who lack adequate health care, jobs and other essentials. Public goods such as schools, according to these politicians and corporate lobbyists, are financial investments, viewed as business opportunities. For the billionaires who are the anti-reformers, teachers, students and unions simply get in the way and must be disciplined.

We need to invest as much, if not more, in education as we do in the military-industrial complex.

Public schools and higher education are «dangerous» because they hold the potential to serve as laboratories for democracy where students learn to think critically. Teachers are threatening because they refuse to conflate education with training or treat schools as if they were car dealerships. Many educators have made it clear that they regard teaching for the test and defining accountability only in numerical terms as acts that dull the mind and kill the spirit of students. Such repressive requirements undermine the ability of teachers to be creative, engage with the communities in which they work and teach in order to make knowledge critical and transformative. The claim that we have too many bad teachers is too often a ruse to hide bad policies and to unleash assaults on public schools by corporate-driven ideologues and hedge fund managers who view schools strictly as investment opportunities for big profits.

We need to praise teachers, hold them to high standards, pay them the salaries they deserve, give them control over their classrooms, reduce class sizes and invest as much, if not more, in education as we do in the military-industrial complex. This is all the more reason to celebrate and call attention to those teachers in Chicago, Detroit and Seattle who are collectively fighting against such attacks on public schools. We need to praise them, learn from them and organize with them because they refuse to treat education as a commodity and they recognize that the crisis of schooling is about the crises of democracy, economic equality and justice. This is not a minor struggle because no democracy can survive without informed citizens.

Neoliberal education is increasingly expressed in terms of austerity measures and market-driven ideologies that undermine any notion of the imagination, reduce faculty to an army of indentured labor and burden students with either a mind-numbing education or enormous crippling debt or both. If faculty and students do not resist this assault, they will no longer have any control over the conditions of their labor, and the institutions of public and higher education will further degenerate into a crude adjunct of the corporation and financial elite.

Clearly, it is time to revisit Mario Savio’s famous speech at Berkeley in 1964 when he called for shutting down an educational system that had become odious. In his own words:

There comes a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part, you can’t even passively take part; and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, the people who own it, that unless you’re free the machine will be prevented from working at all.

Savio’s call to resistance is more relevant today than it was then. Public schools not only mimic the injustices of an oppressive economic system, but also funnel poor youth of color into the criminal legal system. The good news is that there is an echo of outrage and resistance now emerging in the United States, especially among young people such as those in the Black Lives Matter movement.

If the major index of any democracy is measured by how a society treats its children, the United States is failing. Fortunately, more and more people are waking up and realizing that the fight for public schooling is not just about higher salaries for teachers; it is about investing in our children and in democracy itself. At the same time, we live in what author Carl Boggs and others have called a permanent warfare state, one in which every space appears to be a battlefield, and the most vulnerable are viewed not only as an imminent threat, but also as the object of potential violence. This suggests that the battle of education must become part of a wider political struggle. This is a struggle that connects assaults on education with the broader war on youth, police violence with the militarization of society and specific instances of racist brutality with the unchecked exercise of the systemic power of finance capital. But the struggle will not be easy.

If the major index of any democracy is measured by how a society treats its children, the United States is failing.

Beneath all of the current brutality, racism and economic predation, there is some hope inspired by the generation of young people who are protesting police violence and the attack on public and higher education and working hard to invent a politics that gets to the root of issues. There is also a glimmer of possibility in those youth who have supported Bernie Sanders but are really demanding a new and more radical definition of politics: Their vision far surpasses that of the left-centrists and liberals of the Democratic Party.

Elections are the ruse of capitalism, and that has never been more clear than at the present moment. On the one side we have Hillary Clinton, a warmonger, a strong supporter of the financial elite and a representative of a neoliberalism that is as brutal as it is cruel. On the other side we have Donald Trump, a circus barker inviting Americans into a den of horrors. And these are the choices that constitute democracy? I don’t think so.

Collective self-delusion will only go so far in the absence of an education system that offers a space for critical learning and dissent, and functions as a laboratory for democracy. There is a tendency to forget in an age dominated by the neoliberal celebration of self-interest and unchecked individualism that public goods matter, that critical thinking is essential to an informed public and that education at the very least should provide students with unsettling ruptures that display the fierce energy of outrage and the hope for a better world.

But a critical education has the capacity to do more. It also has the power not only to prevent justice from going dead in ourselves and the larger society, but also, in George Yancy’s poetic terms, to teach us how to «love with courage.» Hopefully, while education cannot solve such problems, it can produce the formative cultures necessary to enable a generation of young people to create a robust third party — a party fueled by social movements demanding the economic and political justice that could allow a radical democracy to come to life.

The scourge of illiteracy and the authoritarian nightmare

At the present historical moment, Americans live in a society in which thinking is viewed as an act of stupidity, and ignorance is treated as a virtue. Literacy is now regarded with disdain, words are reduced to data, and science is confused with pseudo-science. For instance, two thirds of the American public believe creationism should be taught in schools and most of the Republicans in Congress do not believe that climate change is caused by human activity, making the U.S. the laughing stock of the world. News has become entertainment and echoes reality rather than interrogating it. Popular culture revels in the spectacles of shock and violence. Unsurprisingly, education in the larger culture has become a disimagination machine, a tool for legitimizing ignorance, and it is central to the formation of an authoritarian politics that has gutted all those public spheres in which thoughtfulness, critical exchange, and informed dialogue can take place.

Illiteracy has become a scourge and a political tool designed primarily to make war on language, meaning, thinking, and the capacity for critical thought. Illiteracy no longer simply marks populations immersed in poverty with little access to quality education; nor does it only suggests the lack of proficient skills enabling people to read and write with a degree of understanding and fluency. More importantly, illiteracy is about what it means not to be able to act from a position of thoughtfulness, informed judgment, and critical agency. It suggests not only learning the skills and knowledge to understand the world but also to intervene in it and change it when necessary. Illiteracy has become a form of political repression that discourages a culture of questioning, renders agency as an act of intervention inoperable, and restages power as a mode of domination. It is precisely this mode of illiteracy that both privatizes and kills the imagination by poisoning it with falsehoods, consumer fantasies, data loops, and the need for instant gratification.

This is a mode of manufactured illiteracy and education that has no language for relating the self to public life, social responsibility or the demands of citizenship. It is important to recognize that the rise of this new mode of illiteracy is not simply about the failure of public and higher education to create critical and active citizens; it is about a society that eliminates those public spheres that make thinking possible while imposing a culture of fear in which there is the looming threat that anyone who holds power accountable will be ignored or punished. At stake here is not only the crisis of a democratic society, but a crisis of memory, ethics, and agency.

What role might education and critical pedagogy have in a society in which the public goods disappear, emotional life collapses into the therapeutic, and education is reduced to either a private affair or a kind of algorithmic mode of regulation in which everything is reduced to a market-based outcome. What role can education play to challenge the deadly claim of casino capitalism that all problems are individual, regardless of whether the roots of such problems lie in larger systemic forces? In a culture drowning in a new love affair with instrumental rationality, it is not surprising that values that are not measurable — compassion, vision, the imagination, trust, solidarity, care for the other, and a passion for justice — wither.

One of the challenges facing the current generation of educators, students, progressives, and other cultural workers is the need to address the role they might play in educating students to be critically engaged agents, attentive to addressing important social issues and being alert to the responsibility of deepening and expanding the meaning and practices of a vibrant democracy. At the heart of such a challenge is the question of what education should accomplish, not simply in a democracy but at an historical moment when the United States is about to slip into the dark night of authoritarianism. In a world in which there is an increasing abandonment of egalitarian and democratic impulses, what will it take to educate young people and the broader polity to challenge authority and hold power accountable? How might we construct an education capable of providing students with the skills, ideas, values, and authority necessary for them to nourish a substantive democracy, recognize anti-democratic forms of power, and to fight deeply rooted injustices in a society and world founded on systemic economic, racial, and gendered inequalities? What will it take for educators to recognize that the culture of education is not simply about the business of culture but is crucial to provide the conditions for students to address how knowledge is related to the power of both self-definition and social agency? What work do educators have to do to create the economic, political, and ethical conditions necessary to endow young people and the general public with the capacities to think, question, doubt, imagine the unimaginable, and defend education as essential for inspiring and energizing the citizens necessary for the existence of a robust democracy?

.

Henry A. Giroux is a widely published social critic and McMaster University professor who holds the McMaster Chair for Scholarship in the Public Interest, the Paulo Freire Distinguished Scholar Chair and is a Visiting Distinguished University Professor at Ryerson University. Born in Rhode Island, he held numerous academic positions in the U.S. and now lives in Hamilton.

Authoritarian Politics in the Age of Civic Illiteracy

The dark times that haunt the current age are epitomized in the monsters that have come to rule the United States and who now dominate the major political parties and other commanding political and economic institutions. Their nightmarish reign of misery, violence, and disposability is also evident in their dominance of a formative culture and its attendant cultural apparatuses that produce a vast machinery of manufactured consent. This is a social formation that extends from the mainstream broadcast media and Internet to a print culture, all of which embrace the spectacle of violence, legitimate opinions over facts, and revel in a celebrity and consumer culture of ignorance and theatrics. Under the reign of this normalized ideological architecture of alleged commonsense, literacy is now regarded with disdain, words are reduced to data, and science is confused with pseudo-science.

Thinking is now regarded as an act of stupidity, and ignorance a virtue. All traces of critical thought appear only at the margins of the culture as ignorance becomes the primary organizing principle of American society. For instance, two thirds of the American public believe that creationism should be taught in schools and most of the Republic Party in Congress do not believe that climate change is caused by human activity, making the U.S. the laughing stock of the world. Politicians endlessly lie knowing that the public is addicted to shocks, which allows them to drown in overstimulation and live in an ever-accelerating overflow of information and images. News has become entertainment and echoes reality rather than interrogating it. Unsurprisingly, education in the larger culture has become a disimagination machine, a tool for legitimating ignorance, and it is central to the formation of an authoritarian politics that has gutted any vestige of democracy from the ideology, policies, and institutions that now control American society.

“Obsolete Man” Burgess Meredith, Twilight Zone, 1961. Public Domain.

I am not talking simply about the kind of anti-intellectualism that theorists such a Richard Hofstadter, Ed Herman and Noam Chomsky, and more recently Susan Jacoby have documented, however insightful their analyses might be. I am pointing to a more lethal form of illiteracy that is often ignored. Illiteracy is now a scourge and a political tool designed primarily to make war on language, meaning, thinking, and the capacity for critical thought. Chris Hedges is right in stating that “the emptiness of language is a gift to demagogues and the corporations that saturate the landscape with manipulated images and the idiom of mass culture.”[1]The new form of illiteracy does not simply constitute an absence of learning, ideas, or knowledge. Nor can it be solely attributed to what has been called the “smartphone society.”[2] On the contrary, it is a willful practice and goal used to actively depoliticize people and make them complicit with the forces that impose misery and suffering upon their lives.

Manufactured Illiteracy, Consumer Fantasies, and the Repression of the Population.

Gore Vidal once called America the United States of Amnesia. The title should be extended to the United States of Amnesia and Willful Illiteracy. Illiteracy no longer simply marks populations immersed in poverty with little access to quality education; nor does it only suggest the lack of proficient skills enabling people to read and write with a degree of understanding and fluency. More profoundly, illiteracy is also about what it means not to be able to act from a position of thoughtfulness, informed judgment, and critical agency. Illiteracy has become a form of political repression that discourages a culture of questioning, renders agency as an act of intervention inoperable, and restages power as a mode of domination. It is precisely this mode of illiteracy that now constitutes the modus operandi of a society that both privatizes and kills the imagination by poisoning it with falsehoods, consumer fantasies, data loops, and the need for instant gratification. This is a mode of manufactured illiteracy and education that has no language for relating the self to public life, social responsibility or the demands of citizenship. It is important to recognize that the rise of this new mode of illiteracy is not simply about the failure of public and higher education to create critical and active citizens; it is about a society that eliminates those public spheres that make thinking possible while imposing a culture of fear in which there is the looming threat that anyone who holds power accountable will be punished. At stake here is not only the crisis of a democratic society, but a crisis of memory, ethics, and agency.

Evidence of such a repressive policy is visible in the growth of the surveillance state, the suppression of dissent, especially among Black youth, the elimination of tenure in states such as Wisconsin, the rise of the punishing state, and the militarization of the police. It is also evident in the demonization, punishing, and war waged by the Obama administration on whistleblowers such as Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning, and Jeffrey Sterling, among others. Any viable attempt at developing a radical politics must begin to address the role of education and civic literacy and what I have termed public pedagogy as central not only to politics itself but also to the creation of subjects capable of becoming individual and social agents willing to struggle against injustices and fight to reclaim and develop those institutions crucial to the functioning and promises of a substantive democracy. One place to begin to think through such a project is by addressing the meaning and role of pedagogy as part of the broader struggle for and practice of freedom.

The reach of pedagogy extends from schools to diverse cultural apparatuses such as the mainstream media, alternative screen cultures, and the expanding digital screen culture. Far more than a teaching method, pedagogy is a moral and political practice actively involved not only in the production of knowledge, skills, and values but also in the construction of identities, modes of identification, and forms of individual and social agency. Accordingly, pedagogy is at the heart of any understanding of politics and the ideological scaffolding of those framing mechanisms that mediate our everyday lives. Across the globe, the forces of free-market fundamentalism are using the educational force of the wider culture and the takeover of public and higher education both to reproduce the culture of business and to wage an assault on the historically guaranteed social provisions and civil rights provided by the welfare state, public schools, unions, women’s reproductive rights, and civil liberties, among others, all the while undercutting public faith in the defining institutions of democracy.

As market mentalities and moralities tighten their grip on all aspects of society, democratic institutions and public spheres are being downsized, if not altogether disappearing. As these institutions vanish—from public schools and alternative media to health care centers– there is also a serious erosion of the discourses of community, justice, equality, public values, and the common good. This grim reality has been called by Alex Honneth a “failed sociality”– a failure in the power of the civic imagination, political will, and open democracy. It is also part of a politics that strips the social of any democratic ideals and undermines any understanding of education as a public good and pedagogy as an empowering practice, a practice which acts directly upon the conditions which bear down on our lives in order to change them when necessary.

George Carlin on government

One of the challenges facing the current generation of educators, students, progressives, and other cultural workers is the need to address the role they might play in educating students to be critically engaged agents, attentive to addressing important social issues and being alert to the responsibility of deepening and expanding the meaning and practices of a vibrant democracy. At the heart of such a challenge is the question of what education should accomplish not simply in a democracy but at a historical moment when the United States is about to slip into the dark night of authoritarianism. What work do educators have to do to create the economic, political, and ethical conditions necessary to endow young people and the general public with the capacities to think, question, doubt, imagine the unimaginable, and defend education as essential for inspiring and energizing the citizens necessary for the existence of a robust democracy? In a world in which there is an increasing abandonment of egalitarian and democratic impulses, what will it take to educate young people and the broader polity to challenge authority and hold power accountable?

What role might education and critical pedagogy have in a society in which the social has been individualized, emotional life collapses into the therapeutic, and education is reduced to either a private affair or a kind of algorithmic mode of regulation in which everything is reduced to a desired outcome. What role can education play to challenge the deadly neoliberal claim that all problems are individual, regardless of whether the roots of such problems like in larger systemic forces. In a culture drowning in a new love affair with instrumental rationality, it is not surprising that values that are not measurable– compassion, vision, the imagination, trust, solidarity, care for the other, and a passion for justice—withers.

A middle school in Lawton, OK. Local News.

Given the crisis of education, agency, and memory that haunts the current historical conjuncture, the left and other progressives need a new language for addressing the changing contexts and issues facing a world in which there is an unprecedented convergence of resources–financial, cultural, political, economic, scientific, military, and technological– increasingly used to exercise powerful and diverse forms of control and domination. Such a language needs to be political without being dogmatic and needs to recognize that pedagogy is always political because it is connected to the acquisition of agency. In this instance, making the pedagogical political means being vigilant about “that very moment in which identities are being produced and groups are being constituted, or objects are being created.”[3] At the same time it means progressives need to be attentive to those practice in which critical modes of agency and particular identities are being denied. It also means developing a comprehensive understanding of politics, one that should begin with the call to reroute single issue politics into a mass social movement under the banner of a defense of the public good, the commons, and a global democracy.

In part, this suggests developing pedagogical practices that not only inspire and energize people but are also capable of challenging the growing number of anti-democratic practices and policies under the global tyranny of casino capitalism. Such a vision suggests resurrecting a radical democratic project that provides the basis for imagining a life beyond a social order immersed in massive inequality, endless assaults on the environment, and elevates war and militarization to the highest and most sanctified national ideals. Under such circumstances, education becomes more than an obsession with accountability schemes, an audit culture, market values, and an unreflective immersion in the crude empiricism of a data-obsessed market-driven society. In addition, it rejects the notion that all levels of schooling can be reduced to sites for training students for the workforce and that the culture of public and higher education is synonymous with the culture of business.

At issue here is the need for progressives to recognize the power of education in creating the formative cultures necessary to both challenge the various threats being mobilized against the ideas of justice and democracy while also fighting for those public spheres, ideals, values, and policies that offer alternative modes of identity, thinking, social relations, and politics. But embracing the dictates of a making education meaningful in order to make it critical and transformative also means recognizing that cultural apparatuses such as the mainstream media and Hollywood films are teaching machines and not simply sources of information and entertainment. Such sites should be spheres of struggle removed from the control of the financial elite and corporations who use them as propaganda and disimagination machines.

Central to any viable notion that what makes pedagogy critical is, in part, the recognition that it is a moral and political practice that is always implicated in power relations because it narrates particular versions and visions of civic life, community, the future, and how we might construct representations of ourselves, others, and our physical and social environment. It is in this respect that any discussion of pedagogy must be attentive to how pedagogical practices work in a variety of sites to produce particular ways in which identity, place, worth, and above all value are organized and contribute to producing a formative culture capable of sustaining a vibrant democracy.[4]

In this instance, pedagogy as the practice of freedom emphasizes critical reflection, bridging the gap between learning and everyday life, understanding the connection between power and difficult knowledge, and extending democratic rights and identities by using the resources of history and theory. However, among many educators, progressives, and social theorists, there is a widespread refusal to recognize that this form of education not only takes place in schools, but is also part of what can be called the educative nature of the culture. At the core of analysing and engaging culture as a pedagogical practice are fundamental questions about the educative nature of the culture, what it means to engage common sense as a way to shape and influence popular opinion, and how diverse educational practices in multiple sites can be used to challenge the vocabularies, practices, and values of the oppressive forces that at work under neoliberal regimes of power.

There is an urgent political need for the American public to understand what it means for an authoritarian society to both weaponize and trivialize the discourse, vocabularies, images, and aural means of communication in a society. How is language used to relegate citizenship to the singular pursuit of cravenly self-interests, legitimate shopping as the ultimate expression of one’s identity, portray essential public services as reinforcing and weakening any viable sense of individual responsibility, and, among other, instances, using the language of war and militarization to describe a vast array of problems we face as a nation. War has become an addiction, the war on terror a Pavlovian stimulant for control, and shared fears one of the few discourses available for defining any vestige of solidarity.

Such falsehoods are now part of the reigning neoliberal ideology proving once again that pedagogy is central to politics itself because it is about changing the way people see things, recognizing that politics is educative and that domination resided not simply in repressive economic structures but also in the realm of ideas, beliefs, and modes of persuasion. Just as I would argue that pedagogy has to be made meaningful in order to be made critical and transformative, I think it is fair to argue that there is no politics without a pedagogy of identification; that is, people have to invest something of themselves in how they are addressed or recognize that any mode of education, argument, idea, or pedagogy has to speak to their condition and provide a moment of recognition.

Lacking this understanding, pedagogy all too easily becomes a form of symbolic and intellectual violence, one that assaults rather than educates. Another example can be seen in the forms of high stakes testing and empirically driven teaching that dominate public schooling in the United States, which amounts to pedagogies of repression which serve primarily to numb the mind and produce what might be called dead zones of the imagination. These are pedagogies that are largely disciplinary and have little regard for contexts, history, making knowledge meaningful, or expanding what it means for students to be critically engaged agents.

The fundamental challenge facing educators within the current age of neoliberalism, militarism, and religious fundamentalism is to provide the conditions for students to address how knowledge is related to the power of both self-definition and social agency. In part, this suggests providing students with the skills, ideas, values, and authority necessary for them to nourish a substantive democracy, recognize anti-democratic forms of power, and to fight deeply rooted injustices in a society and world founded on systemic economic, racial, and gendered inequalities. A as Hannah Arendt, once argued in “The Crisis of Education,” the centrality of education to politics is also manifest in the responsibility for the world that cultural workers have to assume when they engage in pedagogical practices that lie on the side of belief and persuasion, especially when they challenge forms of domination.

Such a project suggests developing a transformative pedagogy–rooted in what might be called a project of resurgent and insurrectional democracy–that relentlessly questions the kinds of labor, practices, and forms of production that are enacted in schools and other sites of education. The project in this sense speaks to the recognition that any pedagogical practice presupposes some notion of the future, prioritises some forms of identification over others, upholds selective modes of social relations, and values some modes of knowing over others (think about how business schools are held in high esteem while schools of education are disdained and even the object in some cases of contempt). Moreover, such a pedagogy does not offer guarantees as much as it recognizes that its own position is grounded in particular modes of authority, values, and ethical principles that must be constantly debated for the ways in which they both open up and close down democratic relations, values, and identities. These are precisely the questions being asked by the Chicago Teachers’ Union in their brave fight to regain some control over both the conditions of their work and their efforts to redefine the meaning of schooling as a democratic public sphere and learning in the interest of economic justice and progressive social change.

Such a project should be principled, relational, contextual, as well as self-reflective and theoretically rigorous. By relational, I mean that the current crisis of schooling must be understood in relation to the broader assault that is being waged against all aspects of democratic public life. At the same time, any critical comprehension of those wider forces that shape public and higher education must also be supplemented by an attentiveness to the historical and conditional nature of pedagogy itself. This suggests that pedagogy can never be treated as a fixed set of principles and practices that can be applied indiscriminately across a variety of pedagogical sites. Pedagogy is not some recipe or methodological fix that can be imposed on all classrooms. On the contrary, it must always be contextually defined, allowing it to respond specifically to the conditions, formations, and problems that arise in various sites in which education takes place. Such a project suggests recasting pedagogy as a practice that is indeterminate, open to constant revision, and constantly in dialogue with its own assumptions.

The notion of a neutral, objective education is an oxymoron. Education and pedagogy do not exist outside of relations of power, values, and politics. Ethics on the pedagogical front demands an openness to the other, a willingness to engage a “politics of possibility” through a continual critical engagement with texts, images, events, and other registers of meaning as they are transformed into pedagogical practices both within and outside of the classroom. Pedagogy is never innocent and if it is to be understood and problematized as a form of academic labor, cultural workers have the opportunity not only to critically question and register their own subjective involvement in how and what they teach in and out of schools, but also to resist all calls to depoliticize pedagogy through appeals to either scientific objectivity or ideological dogmatism. This suggests the need for educators to rethink the cultural and ideological baggage they bring to each educational encounters; it also highlights the necessity of making educators ethically and politically accountable and self-reflective for the stories they produce, the claims they make upon public memory, and the images of the future they deem legitimate. Understood as a form of militant hope, pedagogy in this sense is not an antidote to politics, a nostalgic yearning for a better time, or for some “inconceivably alternative future.” Instead, it is an “attempt to find a bridge between the present and future in those forces within the present which are potentially able to transform it.”[5]

At the dawn of the 21st century, the notion of the social and the public are not being erased as much as they are being reconstructed under circumstances in which public forums for serious debate, including public education, are being eroded. Reduced either to a crude instrumentalism, business culture, or defined as a purely private right rather than a public good, our major educational apparatuses are removed from the discourse of democracy and civic culture. Under the influence of powerful financial interests, we have witnessed the takeover of public and increasingly higher education and diverse media sites by a corporate logic that both numbs the mind and the soul, emphasizing repressive modes of ideology hat promote winning at all costs, learning how not to question authority, and undermining the hard work of learning how to be thoughtful, critical, and attentive to the power relations that shape everyday life and the larger world. As learning is privatized, depoliticized, and reduced to teaching students how to be good consumers, any viable notions of the social, public values, citizenship, and democracy wither and die.

As a central element of a broad based cultural politics, critical pedagogy, in its various forms, when linked to the ongoing project of democratization can provide opportunities for educators and other cultural workers to redefine and transform the connections among language, desire, meaning, everyday life, and material relations of power as part of a broader social movement to reclaim the promise and possibilities of a democratic public life. Critical pedagogy is dangerous to many people and others because it provides the conditions for students and the wider public to exercise their intellectual capacities, embrace the ethical imagination, hold power accountable, and embrace a sense of social responsibility.

One of the most serious challenges facing teachers, artists, journalists, writers, and other cultural workers is the task of developing a discourse of both critique and possibility. This means developing discourses and pedagogical practices that connect reading the word with reading the world, and doing so in ways that enhance the capacities of young people as critical agents and engaged citizens. In taking up this project, educators and others should attempt to create the conditions that give students the opportunity to become critical and engaged citizens who have the knowledge and courage to struggle in order to make desolation and cynicism unconvincing and hope practical. But raising consciousness is not enough. Students need to be inspired and energized to address important social issues, learning to narrate their private troubles as public issues, and to engage in forms of resistance that are both local and collective, while connecting such struggles to more global issues.

Democracy begins to fail and political life becomes impoverished in the absence of those vital public spheres such as public and higher education in which civic values, public scholarship, and social engagement allow for a more imaginative grasp of a future that takes seriously the demands of justice, equity, and civic courage. Democracy should be a way of thinking about education, one that thrives on connecting equity to excellence, learning to ethics, and agency to the imperatives of social responsibility and the public good. The question regarding what role education should play in democracy becomes all the more urgent at a time when the dark forces of authoritarianism are on the march in the United States. As public values, trust, solidarities, and modes of education are under siege, the discourses of hate, racism, rabid self-interest, and greed are exercising a poisonous influence in American society, most evident in the discourse of the right-wing extremists such as Donald Trump and Ted Cruz, vying for the American presidency. Civic illiteracy collapses opinion and informed arguments, erases collective memory, and becomes complicit with the militarization of both individual, public spaces, and society itself. Under such circumstances, politicians such as Hilary Clinton are labeled as liberals when in reality they are firm advocates for both a toxic militarism and the interests of the financial elites.

All across the country, there are signs of hope. Young people are protesting against student debt; environmentalists are aggressively fighting corporate interests; the Chicago Teachers Union is waging a brave fight against oppressive neoliberal modes of governance; Black youth are bravely resisting and exposing state violence in all of its forms; prison abolitionists are making their voices heard, and once again the threat of a nuclear winter is being widely discussed. In the age of financial and political monsters, neoliberalism has lost its ability to legitimate itself in a warped discourse of freedom and choice. Its poisonous tentacles have put millions out of work, turned many Black communities into war zones, destroyed public education, flagrantly pursued war as the greatest of national ideals, turned the prison system into a default institution for punishing minorities of race and class, pillaged the environment, and blatantly imposed a new mode of racism under the silly notion of a post-racial society.

The extreme violence perpetuated in the daily spectacles of the cultural apparatuses are now becoming more visible in the relations of everyday life making it more difficult for many American to live the lie that they are real and active participants in a democracy. As the lies are exposed, the economic and political crises ushering in authoritarianism are now being matched by a crisis of ideas. If this momentum of growing critique and collective resistance continues, the support we see for Bernie Sanders among young people will be matched by an increase in the growth of other oppositional groups. Groups organized around single issues such as an insurgent labor movements, those groups trying to reclaim public education as a public good, and other emerging movements will come together hopefully, refusing to operate within the parameters of established power while working to create a broad-based social movement. In the merging of the power, culture, new public spheres, new technologies, and old and new social movements, there is a hint of a new collective political sensibility emerging, one that offers a new mode of collective resistance and the possibility of taking democracy off life-support. This is not a struggle over who will be elected the next president or ruling party of the United States, but a struggle over those who are willing to fight for a radical democracy and those who are not. The strong winds of resistance are in the air, rattling established interests, forcing liberals to recognize their complicity with established power, and giving new life the meaning of what it means to fight for a democratic social order in which equity and justice prevail for everyone.

Notes.

[1] Chris Hedges, “The War on Language”, TruthDig, (September 28, 2009)

online at: http://www.truthdig.com/report/item/20090928_the_war_on_language/

[2] Nicole Aschoff, “The Smartphone Society,” Jacobin Magazine, Issue 17, (Spring 2015). Online at: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/03/smartphone-usage-technology-aschoff/

[3] Gary Olson and Lynn Worsham, “Staging the Politics of Difference: Homi Bhabha’s Critical Literacy,” Journal of Advanced Composition (1999), pp. 3-35.

[4]. Henry A. Giroux, Education and the Crisis of Public Values, 2nd edition (New York: Peter Lang, 2015).

[5]. Terry Eagleton, The Idea of Culture (Malden, MA: Basil Blackwell, 2000), p.22.

Radical Politics in the Age of American Authoritarianism: Connecting the Dots

The United States stands at the endpoint of a long series of attacks on democracy, and the choices faced by many in the US today point to the divide between those who are and those who are not willing to commit to democracy. Debates over whether Donald Trump is a fascist are a tactical diversion because the real issue is what it will take to prevent the United States from sliding further into a distinctive form of authoritarianism.

The willingness of contemporary politicians and pundits to use totalitarian themes echoes alarmingly fascist and totalitarian elements of the past. This willingness also prefigures the emergence of a distinctive mode of authoritarianism that threatens to further foreclose venues for social justice and civil rights. The need for resistance has become urgent. The struggle is not over specific institutions such as higher education or so-called democratic procedures such as elections but over what it means to get to the root of the problems facing the United States and to draw more people into subversive actions modeled after both historical struggles from the days of the underground railroad and contemporary movements for economic, social and environmental justice.

If progressives are to join in the fight against authoritarianism in the US, we all need to connect issues.

Yet, such struggles will only succeed if more progressives embrace an expansive understanding of politics, not fixating singularly on elections or any other issue but rather emphasizing the connections among diverse social movements. An expansive understanding such as this necessarily links the calls for a living wage and environment justice to calls for access to quality health care and the elimination of the conditions fostering assaults by the state against Black people, immigrants, workers and women. The movement against mass incarceration and capital punishment cannot be separated from a movement for racial justice; full employment; free, quality health care and housing. Such analyses also suggest the merging of labor unions and social movements, and the development of progressive cultural apparatuses such as alternative media, think tanks and social services for those marginalized by race, class and ethnicity. These alternative apparatuses must also embrace those who are angry with existing political parties and casino capitalism but who lack a critical frame of reference for understanding the conditions for their anger.

What is imperative in rethinking the space of the political is the need to reach across specific identities and stop mobilizing exclusively around single-issue movements and their specific agendas. As the Fifteenth Street Manifesto Group expressed in its 2008 piece, «Left Turn: An Open Letter to US Radicals,» many groups on the left would grow stronger if they were to «perceive and refocus their struggles as part of a larger movement for social transformation.» Our political agenda must merge the pedagogical and the political by employing a language and mode of analysis that resonates with people’s needs while making social change a crucial element of the political and public imagination. At the same time, any politics that is going to take real change seriously must be highly critical of any reformist politics that does not include both a change of consciousness and structural change.

If progressives are to join in the fight against authoritarianism in the United States, we all need to connect issues, bring together diverse social movements and produce long-term organizations that can provide a view of the future that does not simply mimic the present. This requires connecting private issues to broader structural and systemic problems both at home and abroad. This is where matters of translation become crucial in developing broader ideological struggles and in fashioning a more comprehensive notion of politics.

There has never been a more pressing time to rethink the meaning of politics, justice, struggle and collective action.

Struggles that take place in particular contexts must also be connected to similar efforts at home and abroad. For instance, the ongoing privatization of public goods such as schools can be analyzed within the context of increasing attempts on the part of billionaires to eliminate the social state and gain control over commanding economic and cultural institutions in the United States. At the same time, the modeling of schools after prisons can be connected to the ongoing criminalization of a wide range of everyday behaviors and the rise of the punishing state. Moreover, such issues in the United States can be connected to other authoritarian societies that are following a comparable script of widespread repression. For instance, it is crucial to think about what racialized police violence in the United States has in common with violence waged by authoritarian states such as Egypt against Muslim protesters. This allows us to understand various social problems globally so as to make it easier to develop political formations that connect such diverse social justice struggles across national borders. It also helps us to understand, name and make visible the diverse authoritarian policies and practices that point to the parameters of a totalitarian society.

There has never been a more pressing time to rethink the meaning of politics, justice, struggle, collective action, and the development of new political parties and social movements. The ongoing violence against Black youth, the impending ecological crisis, the use of prisons to warehouse people who represent social problems, and the ongoing war on women’s reproductive rights, among other crises, demand a new language for developing modes of creative long-term resistance, a wider understanding of politics, and a new urgency to create modes of collective struggles rooted in more enduring and unified political formations. The American public needs a new discourse to resuscitate historical memories and methods of resistance to address the connections between the escalating destabilization of the earth’s biosphere, impoverishment, inequality, police violence, mass incarceration, corporate crime and the poisoning of low-income communities.

Not only are social movements from below needed, but also there is a need to merge diverse single-issue movements that range from calls for racial justice to calls for economic fairness. Of course, there are significant examples of this in the Black Lives Matter movement (as discussed by Alicia Garza, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor andElizabeth Day) and the ongoing strikes by workers for a living wage. But these are only the beginning of what is needed to contest the ideology and supporting apparatuses of neoliberal capitalism.

The call for broader social movements and a more comprehensive understanding of politics is necessary in order to connect the dots between, for instance, police brutality and mass incarceration, on the one hand, and the diverse crises producing massive poverty, the destruction of the welfare state and the assaults on the environment, workers, young people and women. As Peter Bohmer observes, the call for a meaningful living wage and full employment cannot be separated from demands «for access to quality education, affordable and quality housing and medical care, for quality child care, for reproductive rights and for clean air, drinkable water,» and an end to the pillaging of the environment by the ultra-rich and mega corporations. He rightly argues:

Connecting issues and social movements and organizations to each other has the potential to build a powerful movement of movements that is stronger than any of its individual parts. This means educating ourselves and in our groups about these issues and their causes and their interconnection.

In this instance, making the political more pedagogical becomes central to any viable notion of politics. That is, if the ideals and practices of democratic governance are not to be lost, we all need to continue producing the critical formative cultures capable of building new social, collective and political institutions that can both fight against the impending authoritarianism in the United States and imagine a society in which democracy is viewed no longer as a remnant of the past but rather as an ideal that is worthy of continuous struggle. It is also crucial for such struggles to cross national boundaries in order to develop global alliances.

Democracy must be written back into the script of everyday life.

At the root of this notion of developing a comprehensive view of politics is the need for educating ourselves by developing a critical formative culture along with corresponding institutions that promote a form of permanent criticism against all elements of oppression and unaccountable power. One important task of emancipation is to fight the dominant culture industry by developing alternative public spheres and educational institutions capable of nourishing critical thought and action. The time has come for educators, artists, workers, young people and others to push forward a new form of politics in which public values, trust and compassion trump neoliberalism’s celebration of self-interest, the ruthless accumulation of capital, the survival-of-the-fittest ethos and the financialization and market-driven corruption of the political system. Political responsibility is more than a challenge — it is the projection of a possibility in which new modes of identification and agents must be enabled that can sustain new political organizations and transnational anti-capitalist movements. Democracy must be written back into the script of everyday life, and doing so demands overcoming the current crisis of memory, agency and politics by collectively struggling for a new form of politics in which matters of justice, equity and inclusion define what is possible.

Such struggles demand an increasingly broad-based commitment to a new kind of activism. As Robin D. G. Kelley has recently noted, there is a need for more pedagogical, cultural and social spaces that allow us to think and act together, to take risks and to get to the roots of the conditions that are submerging the United States into a new form of authoritarianism wrapped in the flag, the dollar sign and the cross. Kelley is right in calling for a politics that places justice at its core, one that takes seriously what it means to be an individual and social agent while engaging in collective struggles. We don’t need tepid calls for repairing the system; instead, we need to invent a new system from the ashes of one that is terminally broken. We don’t need calls for moral uplift or personal responsibility. We need calls for economic, political, gender and racial justice. Such a politics must be rooted in particular demands, be open to direct action and take seriously strategies designed to both educate a wider public and mobilize them to seize power.

The left needs a new political conversation that encompasses memories of freedom and resistance. Such a dialogue would build on the militancy of the labor strikes of the 1930s, the civil rights movements of the 1950s and the struggle for participatory democracy by the New Left in the 1960s. At the same time, there is a need to reclaim the radical imagination and to infuse it with a spirited battle for an independent politics that regards a radical democracy as part of a never-ending struggle.

None of this can happen unless progressives understand education as a political and moral practice crucial to creating new forms of agency, mobilizing a desire for change and providing a language that underwrites the capacity to think, speak and act so as to challenge the sexist, racist, economic and political grammars of suffering produced by the new authoritarianism.

The left needs a language of critique that enables people to ask questions that appear unspeakable within the existing vocabularies of oppression. We also need a language of hope that is firmly aware of the ideological and structural obstacles that are undermining democracy. We need a language that reframes our activist politics as a creative act that responds to the promises and possibilities of a radical democracy.

Movements require time to mature and come into fruition. They necessitate educated agents able to connect structural conditions of oppression to the oppressive cultural apparatuses that legitimate, persuade, and shape individual and collective attitudes in the service of oppressive ideas and values. Under such conditions, radical ideas can be connected to action once diverse groups recognize the need to take control of the political, economic and cultural conditions that shape their worldviews, exploit their labor, control their communities, appropriate their resources, and undermine their dignity and lives. Raising consciousness alone will not change authoritarian societies, but it does provide the foundation for making oppression visible and for developing from below what Étienne Balibar calls «practices of resistance and solidarity.» We need not only a radical critique of capitalism, racism and other forms of oppression, but also a critical formative culture and cultural politics that inspire, energize and provide elements of a transformative radical education in the service of a broad-based democratic liberation movement.

May not be reprinted without permission of the author

Users Today : 30

Users Today : 30 Total Users : 35459625

Total Users : 35459625 Views Today : 72

Views Today : 72 Total views : 3418044

Total views : 3418044