Mirador.org.Bo

El aprendizaje está en crisis. La calidad y cantidad en términos educativos varían considerablemente dentro de los países y de un país a otro. Cientos de millones de niños crecen sin contar siquiera con las habilidades más básicas en todo el mundo.

En el Informe sobre el desarrollo mundial se recurre a disciplinas tan variadas como la economía y la neurociencia para analizar esta cuestión y se sugieren mejoras que los países pueden implementar. Usted puede consultar los mensajes principales, el panorama general o descargar el informe completo aquí [PDF en inglés]. A modo de anticipo, extraje algunos gráficos e ideas que me parecieron muy interesantes mientras lo leía.

En el informe se presentan varios argumentos a favor del valor de la educación. ¿Cuál es, para mí, el más claro? El que dice que la educación es una herramienta poderosa para aumentar los ingresos. Con cada año adicional de escolarización, los ingresos de una persona aumentan entre un 8 % y un 10 %, especialmente en el caso de las mujeres. Esto no se debe únicamente a que más personas capacitadas y mejor conectadas reciben más educación: en “experimentos naturales” realizados en una variedad de países —como Estados Unidos, Filipinas, Honduras, Indonesia y Reino Unido— se prueba que la escolarización realmente contribuye al aumento de los ingresos. Un mayor nivel de educación también se asocia a una vida más larga y más sana, y genera beneficios a largo plazo para las personas y para la sociedad en su conjunto.

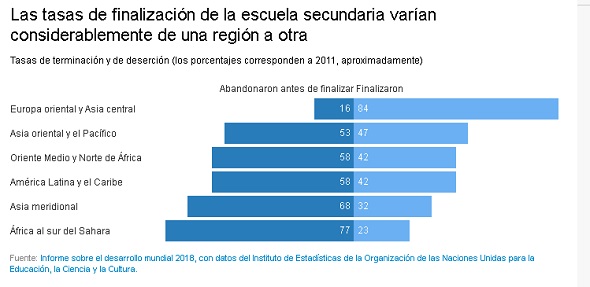

A pesar de estos beneficios potenciales, los jóvenes siguen diferentes caminos en su educación. En los países de ingreso bajo y mediano, de cada 100 estudiantes que ingresan a la educación primaria, 90 completan la educación primaria, 61 completan el ciclo inferior de la secundaria y solo 35 completan el ciclo superior de la secundaria. Esto significa que alrededor de un tercio de los jóvenes abandona la escuela entre el ciclo inferior y el ciclo superior de la secundaria, y muchos de ellos no están preparados para continuar con su educación y la capacitación.

Lo que importa en materia de educación no es solo la cantidad sino la calidad. Si bien resulta difícil medir el aprendizaje de una manera que permita la comparación entre los distintos países, en el informe se toman como base estudios que tienen precisamente ese objetivo. La Base de Datos Mundial sobre Calidad de la Educación, actualizada recientemente, sugiere que en los países de ingreso bajo y mediano más del 60 % de los niños de la escuela primaria no lograr adquirir una competencia mínima en matemática y lectura. Por el contrario, en los países de ingreso alto, casi todos los niños alcanzan este nivel en la primaria.

No solo hay disparidades entre los distintos países, sino también dentro de ellos. La que me resulta más impactante es mayormente una consecuencia de la pobreza. Casi 1 de cada 3 niños menores de 5 años en los países de ingreso bajo y mediano presenta retraso del crecimiento, por lo general debido a la malnutrición crónica. Este tipo de privación —relacionada con la falta de nutrición adecuada o de un entorno sano— produce efectos a largo plazo en el desarrollo cerebral. Por lo tanto, incluso cuando las escuelas son, los niños que sufren privaciones (normalmente, los más pobres) aprenden menos. Por otra parte, a medida que los niños crecen resulta más difícil romper este patrón, debido a que el cerebro se vuelve menos maleable y les cuesta más aprender nuevas habilidades.

Los estudiantes no son los únicos que fallan: las escuelas también les fallan a los estudiantes. En siete países africanos, 1 de cada 5 docentes, en promedio, se había ausentado de la escuela el día en que los equipos de encuestadores realizaron una visita sin anunciar, y 2 de cada 5 no estaban en el aula aunque se encontraban presentes en la escuela. En las comunidades aisladas, estos problemas son incluso más graves. En este tipo de análisis no se pretende culpar a los docentes, sino más bien llamar la atención sobre cuestiones sistemáticas, como la dotación de recursos, la gestión y la gobernanza, que suelen menoscabar la calidad del aprendizaje.

Para abordar la crisis del aprendizaje, la primera recomendación del informe es contar con más y mejores sistemas que permitan medir el aprendizaje. Si bien los medios de comunicación y los debates sobre educación a menudo se centran en la cuestión del “exceso de pruebas” y los exámenes nacionales de alto perfil, una mirada a los datos disponibles sugiere que muchos países incluso carecen de información sobre el aprendizaje básico. En un estudio de 121 países se concluyó que un tercio de esos países carecía de los datos sobre los niveles de competencia lectora y en matemática de los niños que terminan la escuela primaria, y que una proporción incluso mayor no disponía de datos correspondientes al final del ciclo inferior de la secundaria.

Si bien los países están dispuestos a invertir en educación, en el informe se sostiene que los Gobiernos no solo deben gastar más, sino que también deben gastar mejor, garantizando de ese modo que los recursos se asignen de manera más eficiente y equitativa. La mayor parte del financiamiento proviene de fuentes internas y, por lo general, absorbe la proporción más importante del presupuesto público: alrededor del 15 % en los países de ingreso bajo y mediano. Si bien esto muestra que los Gobiernos reconocen la importancia de la educación, en el informe se sostiene que para mejorar el aprendizaje no basta con aumentar el gasto solamente.

Dos siglos de crecimiento en la escolarización secundaria

A pesar de todos los desafíos señalados en el informe, vale la pena retroceder un poco para reconocer los avances que se han logrado en el campo de la educación a nivel mundial durante los últimos 200 años. Hoy en día, la mayoría de los niños tiene acceso a la educación básica y cada generación nueva pasa más tiempo en la escuela que la anterior. La cantidad de años de escolaridad que un adulto promedio completa en un país de ingreso bajo o mediano aumentó a más del triple desde 1950 hasta 2010 al pasar de 2 a 7,2 años. Esta tasa no conoce precedentes. Estados Unidos demoró 40 años (de 1870 a 1910) para llevar la tasa de matriculación de las niñas del 57 % al 88 %, mientras que Marruecos logró un incremento similar en solo 10 años.

Estos fueron algunos de los gráficos e ideas que resultaron muy interesantes del Informe sobre el desarrollo mundial 2018, dedicado a la educación. Hay mucho más para consultar en el documento, que usted podrá descargar aquí.

Fuente: http://mirador.org.bo/?p=26985

Users Today : 43

Users Today : 43 Total Users : 35474790

Total Users : 35474790 Views Today : 48

Views Today : 48 Total views : 3574841

Total views : 3574841