EEUU/May 22, 2018/Source: http://www.mlive.com

There’s no way around it: Michigan’s education system is floundering.

From early literacy to middle-school math, Michigan students are not keeping up with their peers in top-performing states.

Big changes are needed if Michigan wants to turn itself around, experts say.

«Michigan, if it thinks the status quo is going to be fine, we’ll have a race to the bottom, and we’re almost there right now,» said Grand Valley State University President Thomas Haas, who chaired Gov. Rick Snyder’s 21st Century Education Commission, a panel that developed recommendations to improve Michigan’s education system.

Perhaps no issue is more important for Michigan’s future: In a global economy, a well-educated workforce is critical – and an area where Michigan lags behind.

It starts with reaching and educating Michigan school children even earlier than kindergarten. That means providing more families with affordable access to high-quality early childhood education and funding K-12 schools based on student need, experts say.

It also means ensuring all children have access to top-notch teachers and boosting the number of residents with college degrees or certificates in areas such as the skilled trades.

The relatively low numbers of college graduates and people with post-secondary training mean good jobs here can go begging. The state’s fast-growing occupations are those that require post-secondary training. In 2016, 2 percent of Michigan adults with a bachelor’s degree were unemployed compared to 7 percent of those with only a high school diploma.

Low rates of educational attainment means stagnating wages and tax bases that stifle economic growth. It means Michigan is less competitive in recruiting new employers. A major reason Detroit wasn’t a finalist in the new Amazon Headquarters was that the region didn’t have the talent pool needed for the jobs.

It hurts individuals. It hurts entire communities.

«It’s really about our vitality in every aspect for the future in our state,» said Amber Arellano, executive director of The Education Trust-Midwest, a nonpartisan education policy and research group. «It’s whether you want to stay here and raise your kids.»

In a series that began in April, MLive is taking a hard look at Michigan’s biggest challenges – our economy, education system and infrastructure – from the historical importance, to how we got where we are today, to possible solutions.

We’ll use the series to frame our discussion with candidates as we head into the 2018 midterm elections and choose Michigan’s newest leaders.

This month, we’re taking a deep dive into Michigan’s educational pipeline.

K-12 schools

Michigan students are below the national average in federal test scores, in graduating high school in four years and in college enrollment.

* Michigan ranked 36th in fourth-grade reading proficiency in the most round of the National Assessment of Educational Progress tests.

* About 80 percent of Michigan’s Class of 2017 graduated high school in four years compared to a national average of 84 percent.

*Not quite 32 percent of Michigan adults age 25 to 34 have a bachelor’s degree compared to 35 percent in that age group nationwide.

And that’s after Michigan has spent the past two decades rolling out various strategies to improve Michigan’s schools.

Michigan has opened the door to school choice and charter schools. Rigorous high school graduation requirements have been implemented. High-stakes testing has been adopted. Teacher tenure laws have been reformed. And a now-defunct state-reform district was created.

Some of those efforts, such as high academic standards, are important and should stay in place, experts say. But overall, they have not pushed the needle in student achievement.

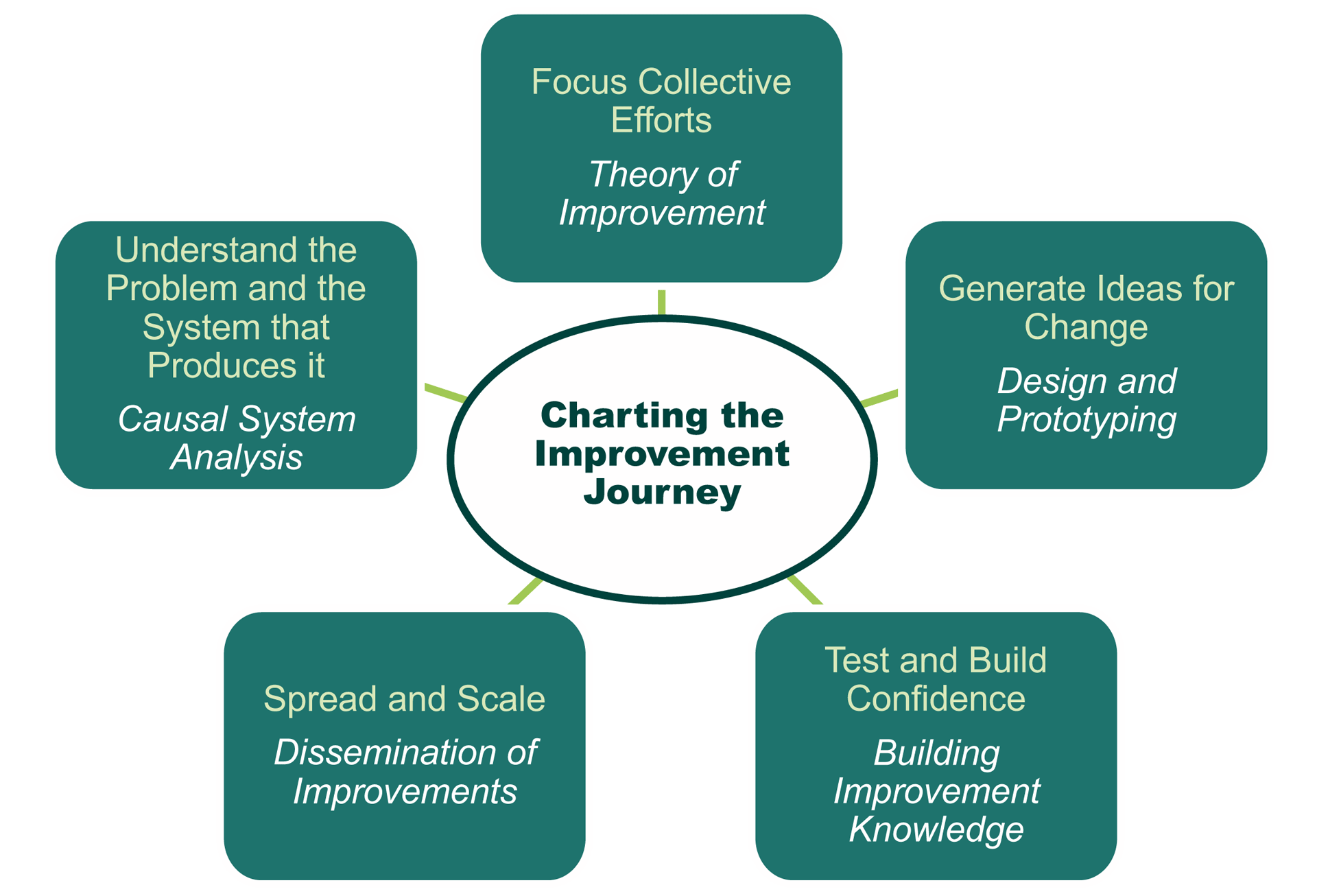

What’s needed, education leaders say, is transformational change.

That includes an overhaul of the school-funding formula, according to the School Finance Research Collaborative, a coalition of educators, nonprofits and philanthropic groups.

Michigan isn’t providing adequate funding for K-12 education, and policymakers must take into greater account the needs of each child, the collaborative said in a January 2018 report.

About half of Michigan students qualify for the subsidized lunch program, and there’s a huge academic achievement gap between those children and students from middle-class and affluent families.

Closing that gap requires more support services: more tutoring and specialized instruction, more after-school programs, more summer school. Michigan’s funding formula needs to reflect those costs, the collaborative says.

Another big issue: Getting more experienced, high-quality teachers in Michigan’s most troubled school districts.

Right now, Michigan’s best teachers tend to gravitate to more affluent districts where the pay tends to be much better and the public support is much greater.

But that shortchanges students in high-poverty communities most in need of skilled, experienced teachers.

Birth to age 5

Another recommendation of the governor’s commission: give more families access to high-quality, early childhood education.

That means offering all 4-year-olds access to state-funded preschool, and helping more families pay for quality childcare for children ages birth to three, educators and advocacy groups say. Currently, slightly less than half of Michigan 3- and 4-year-olds attend a pre-K program, according to Census data.

«People can’t afford or don’t have access to quality child care in their communities,» said Matt Gillard, president and CEO of Michigan’s Children, which advocates for services for low-income families. «This is a huge challenge right now.»

Research shows that 90 percent of brain development occurs in the first five years of life, which means birth-to-5 services offer the best bang for the buck for improving academic outcomes.

Higher education

Investments are crucial in higher education, too.

By 2020, about two-thirds of jobs are expected to require training beyond high school, whether that be a college degree or an associate degree or certificate in areas such as advanced manufacturing or information technology.

Yet Michigan lags in the number of college graduates and people with post-secondary training. About 28 percent of Michigan adults age 25 and older have a bachelor’s degree, compared to a national average of 31 percent.

Boosting Michigan’s number is key if the state wants to lure employers to the state and ensure that residents have the skills needed to land good, high-paying jobs, said Lou Glazer, president of Michigan Future Inc., a nonprofit organization focused on improving the state’s economy.

«The choice is increase college attainment or permanently be one of the poorer states in the country,» Glazer said. «That’s the stakes.»

Over the course of the next several months, MLive will explore issues of economy, education and infrastructure, and what Michigan leaders need to do to create a better future. We’d love to hear from you, about your struggles and your wins, as you navigate Michigan’s economic landscape. We want to use your voice and your questions to frame the conversation with candidates as we head into midterm elections. Have a story to share, send us an email to michiganbeyond@mlive.com

Source:

http://www.mlive.com/news/index.ssf/2018/05/michigan_beyond_education.html

Users Today : 97

Users Today : 97 Total Users : 35461178

Total Users : 35461178 Views Today : 246

Views Today : 246 Total views : 3421078

Total views : 3421078