By: Saitō Katsuhisa.

A World First

Under the Egypt-Japan Education Partnership administered by the Japan International Cooperation Agency, Egypt is the first country in the world to adopt tokkatsu, an integral part of Japanese education, throughout its school system.

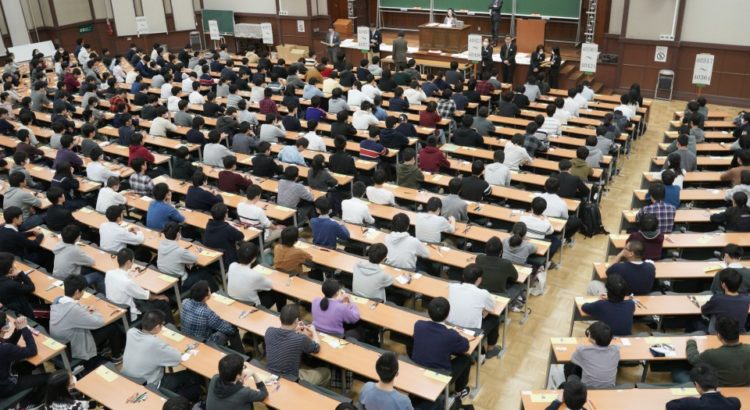

Egypt, a leading Arab nation, is famed for its pyramids, but its education system is rife with problems. Teachers are poorly paid and frequently moonlight as tutors or cram school operators, practices that parents have complained about. Under pressure to excel academically, students may fail to develop well-rounded personalities. Since there are too few schools to meet demand, classes with 70 or 80 pupils are not unusual, and school graduates are increasingly failing to find jobs. Given these myriad issues, the government decided that the time was ripe for educational reforms.

Egypt’s president, Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi, has always been highly impressed by punctual, industrious Japanese, whom he has called “a walking embodiment of the Quran.” In the Arab world, it is commonly believed that Japan’s education system has been key to its success as an advanced nation. Sisi, visiting Japan in 2016, concluded the EJEP agreement with Japan to introduce elements of Japanese schooling into all levels of the Egyptian education system.

Egypt-Japan Schools Opened

Egypt’s education authorities saw tokkatsu—activities outside of school subjects intended to foster children’s all-round development—in Japanese elementary schools as a way of nurturing well-rounded individuals in Egypt. Tokkatsu including class meetings were introduced on a trial basis in 12 public schools, and 35 brand-new Egypt-Japan Schools opened in September 2018. At these schools, tokkatsu are part of the school day, and the schools follow Japanese operational methods. Kakehashi Tarō, an assistant director in JICA’s Basic Education Group, says that 45 minutes per week of tokkatsuactivities were incorporated into the curriculum for first graders at all elementary schools in the country at the same time.

Tokkatsu includes a number of key activities. Class meetings, where pupils discuss and decide on topics for schoolwide events, help them learn to express their ideas and respect those of others. Guidance consists of helping pupils to acquire good habits like washing their hands and brushing their teeth, training them to give proper greetings, and encouraging them to be considerate of others. All pupils take the role of class leader of the day in turn; this teaches children leadership and gives them the experience of leading the class. Egypt’s education system has never included activities like tokkatsubefore, so this has been a novel experience.

Children brushing their teeth after lunch. This activity is part of overall guidance to promote good hygiene. More children are now participating voluntarily.

Unlike schools for Japanese children living abroad, EJS institutions are tokkatsu model public schools attended by local children. The schools have introduced practices common in Japan, such as study periods and classroom cleaning by pupils, intramural seminars where teachers observe each others’ classes and offer teaching hints, and school staff meetings.

Children Cleaning Classrooms: A Novel Experience

One tokkatsu practice that raised issues was cleaning. In Japanese schools, pupils clean their classrooms and other parts of their schools as a matter of course. In Egypt, though, cleaning is viewed as a menial task carried out by the lower classes, and children and their parents alike were shocked that they were expected to clean. Some pupils initially refused to participate, and parents also protested, saying they were not sending their children to an EJS to clean. But the idea of everyone working together to keep classrooms and other spaces clean is starting to take hold. Some pupils started cleaning, and others, seeing their friends doing so, eventually joined in. Everyone learned to keep their desks neat and tidy too.

Classroom cleaning. Some pupils disliked the idea at first, but now most participate in this activity meant to teach teamwork.

JICA education experts make the rounds of EJSs and continue to offer advice. Up to now, 42 people, including school principals and teachers in charge of introducing tokkatsu, have participated in month-long training sessions in Japan that include a first-hand look at Japanese schools in action. Over the next four years, JICA envisages bringing a total of about 700 teachers to Japan for similar training.

These schools have been in operation for barely a year now but are already showing results. For example, EJS attendees have shown solid progress in listening to what their classmates are saying and respecting their ideas. Tardiness is also less of a problem now, children are quarreling less at school, and more children are helping with chores at home.

Egypt-Japan Schools offer a pleasant environment: The buildings are new and class sizes, at around 35 to 40 pupils, are about half the size of classes at other public schools. Tuition, however, is expensive, costing the equivalent of ¥60,000 to ¥70,000 yearly, which is 5 to 10 times the tuition at regular schools. According to JICA’s Kakehashi, “There are no EJS entrance examinations, but we have asked the Egyptian authorities to ensure that the schools don’t turn into places just for children from high-income families. We hope the government will offer more scholarships and make it easier for those who want to enter EJS institutions to do so.”

Developing Human Resources

Ayman Ali Kamel, Egypt’s ambassador to Japan, says that through the EJS program, “Egypt hopes to learn from Japan’s experience to contribute to social progress and effect comprehensive reforms to the education system. We view classrooms and elementary schools as miniature societies, and we hope that these societies will inculcate a sense of morality in our children and help mold their personalities.”

Hany Helal, Egypt’s former minister of higher education and scientific research, who worked as a coordinator between Egypt and Japan to set up the EJEP and other projects, comments: “The most important issue for Egypt is developing high-quality human resources, which has been difficult to accomplish with our existing education system. We hope to improve our learning environment by introducing features of Japanese education like tokkatsu to nurture the upcoming generation driving our country’s future.”

Source of article: https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-topics/g00727/bringing-japanese-educational-approaches-to-egyptian-schools.html

Users Today : 6

Users Today : 6 Total Users : 35460137

Total Users : 35460137 Views Today : 10

Views Today : 10 Total views : 3418793

Total views : 3418793