Francia/Septiembre de 2017/Fuente: The Economist

Resumen: La característica más destacada del aula de Sandy Sablon en la escuela primaria Oran-Constantine, en las afueras del puerto norte de Calais, es la colección de viejas pelotas de tenis que ha acuñado en las piernas de todas las sillas. El maestro pasó un fin de semana cortando y ajustando las bolas verde lima para reducir el ruido. Esto se convirtió en un problema cuando ella introdujo nuevos métodos de enseñanza. Fuera salieron escritorios en filas. En cambio, agrupó a niños de un nivel similar de logros alrededor de mesas compartidas, lo que significó que los alumnos se levantaron y se mudaron mucho más. Todas las tensiones de la Francia postindustrial se aglomeran en Fort Nieulay, el barrio de Calais que rodea la escuela. Las casas adosadas de ladrillo rojo, construidas para las familias de trabajadores portuarios y trabajadores industriales en los años cincuenta, se proyectan contra bloques de torres llenos de lluvia. Los columpios de los niños están rotos. Sophie Paque, la cabeza enérgica de la primaria, dice que un asombroso 89% de sus alumnos viven por debajo de la línea de pobreza. «Les damos una estructura que no tienen en casa». El desempleo juvenil en Calais es más del 45%, el doble del promedio nacional. En Fort Nieulay toca el 67%.

THE MOST STARTLING feature of Sandy Sablon’s classroom at the Oran-Constantine primary school, on the outskirts of the northern port of Calais, is the collection of old tennis balls that she has wedged on to the legs of all the little chairs. The teacher spent a weekend gashing and fitting the lime-green balls in order to cut down noise. This became a problem when she introduced new teaching methods. Out went desks in rows. Instead, she grouped children of a similar level of achievement around shared tables, which meant pupils got up and moved about much more.

All the strains of post-industrial France crowd into Fort Nieulay, the Calais neighbourhood surrounding the school. Red-brick terraced houses, built for the families of dockers and industrial workers in the 1950s, jut up against rain-streaked tower blocks. On the estate, the Friterie-Snack Bar is open for chips, but other shop fronts are boarded up. The children’s swings are broken. Sophie Paque, the primary’s energetic head, says a staggering 89% of her pupils live below the poverty line. “We give them a structure they don’t have at home.” Youth unemployment in Calais is over 45%, twice the national average. In Fort Nieulay it touches 67%.

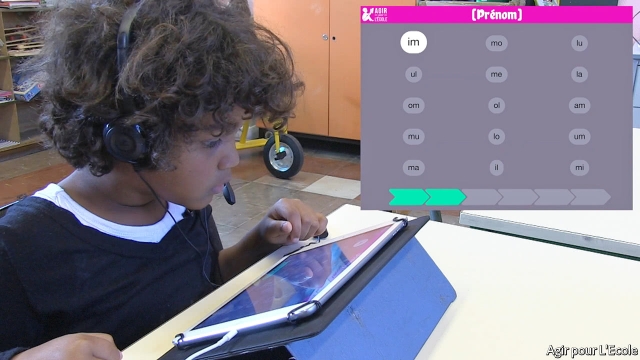

This autumn Oran-Constantine, like 2,500 other priority classes nationwide, is benefiting from Mr Macron’s promise to halve class sizes to 12 pupils for five- and six-year-olds. The new policy caused a certain amount of chaos elsewhere, but Oran-Constantine was ready. It had already been part of a pilot scheme launched in 2011, with smaller class sizes for rigorous new reading sessions and more personalised learning. This was put in place under an education official, Jean-Michel Blanquer, who is now Mr Macron’s education minister. Faster learners use voice-recognition software on tablet computers, freeing up their teacher to help weaker classmates. “French teachers tend to advance like steamrollers: straight ahead at the same speed,” says Christophe Gomes, from Agir pour l’Ecole, the partly privately financed association that ran the government-backed pilot scheme; here “pupils set the pace.” Some teachers feared that technology was threatening their jobs, but found instead that it allowed them to do their jobs better. One year into the experiment, the number of pupils with reading difficulties at the 11 schools in Calais that took part had halved.

The challenge is to persuade public opinion, students, parents and teachers that variety, autonomy and experimentation are not a threat to equality

Such techniques may not seem controversial elsewhere, but in France they challenge central educational tenets. For many years, education has been subject to what might be called “the tyranny of normal”. Ever since Jules Ferry introduced compulsory, free, secular primary education in the 1880s, uniform schooling countrywide has been part of the French way of doing things. The 19th-century instituteur, or schoolteacher, was a missionary figure, a guarantor of republican equality and norms. Teachers were trained in écoles normales. To this day, the mighty education ministry sets standardised curriculums and timetables. All 11-year-olds spend exactly four-and-a-half hours on maths a week. Experimentation is frequently regarded as suspect. “Classes are not laboratories,” noted a report by the conservative education inspectorate a few years ago, “and pupils are not guinea pigs.”

Yet “in reality our standardising system is unequal,” says Mr Blanquer. By the age of 15, 40% of French pupils from poorer backgrounds are “in difficulty”, a figure six percentage points above the OECD average. French schools, with their demanding academic content and testing, do well by the brightest children, but often fail those at the bottom. France is an “outlier”, says Eric Charbonnier, an OECD education specialist, because in contrast to most countries, inequality in education has actually increased over the past decade. Trouble starts in the first year of primary school, when children move abruptly from finger-painting in maternelle (nursery) to sitting in rows learning to read and write. Weaker pupils quickly get left behind and find it hard to catch up.

Mr Macron and Mr Blanquer have put reform of primary education at the centre of their policy to combat school failure and improve life chances. Halving class sizes is just the start. Mr Blanquer, a former director of Essec, a highly regarded business school, has thought about what works abroad and how such lessons might be applied in France. He is keen on autonomy and experimentation, which puts the teaching profession on edge. French education has long been run along almost military lines. An army of 880,000 teachers is deployed to schools across the country. Head teachers have no say in staffing. In the course of their careers, teachers acquire points that enable them to request reassignment. Newly qualified ones without such points are sent to the toughest schools, and turnover in such places is depressingly high.

During the election campaign Mr Macron promised to give schools more autonomy over teaching methods, timetabling and recruitment, and to stop newly qualified teachers from being sent to the toughest schools. Yet greater freedom for schools to experiment will require a big change in thinking. Only just over 20% of French teachers adjust their methods to individual ability, compared with over 65% of those in Norway.

At the other end of the education ladder, a hint of just how creative independent French education can be is found inside a boxy building on the inner edge of northern Paris. This is 42, a coding school. It is named after the number that is the “answer to the ultimate question of life, the universe and everything”, according to Douglas Adams’s science-fiction classic, “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy”. The entrance hall at 42 is all distressed concrete and exposed piping. There is a skateboard rack and a painting of a man urinating against a graffiti-sprayed wall.

Metaphysics and meritocracy

42 is everything that traditional French higher education is not. It is entirely privately financed by Mr Niel, the entrepreneur, but free to pupils. It holds no classes, has no fixed terms or timetables and does not issue formal diplomas. All learning is done through tasks on screen, at students’ own pace; “graduates” are often snapped up by employers before they finish. There are no lectures, and the building is open round the clock. The school is hyper-selective and has a dropout rate of 5%. When it opened in 2013, Le Monde, a newspaper, described it as “strange”. “We’re not about the transmission of knowledge,” says Nicolas Sadirac, the director. “We are co-inventing computer science.” He likes to call 42 an art school.

On a weekday morning Guillaume Aly politely takes off his headphones to answer questions as he arrives at 42. He was in the army for eight years before he applied, and went to school in Seine-Saint-Denis, a nearby banlieue, or outer suburb, where joblessness is well above the national average. “I’m 30 years old, and you don’t have much hope of training at my age,” he says. But 42 shows a deliberate disregard for social background or exam results. It tests applicants anonymously online, then selects from a shortlist after a month-long immersion. Each year 50,000-60,000 people apply and just 900 are admitted. Léonard Aymard, originally from Annecy, was a tour guide when he applied. Loic Shety, from Dijon, won a place even though he lacked the school-leaving baccalauréat certificate. “It’s not for everyone,” says Mathilde Allard from Montpellier, “but we work together so we don’t get lost.”

Across the river Seine, on the capital’s chic left bank, the University of Paris-Descartes is a world away from 42. It is based in a late-18th-century building. Home to one of the most prestigious medical schools in France, it is highly sought after by the capital’s brightest, and is a world-class centre of research in medical and life sciences. Yet a glimpse at Descartes also shows how French higher education can tie the hands of innovators, including the university’s president, Frédéric Dardel, a molecular biologist.

Like universities the world over, Descartes receives far more applications than it has places available. Yet unlike university heads in other countries, Mr Dardel is not permitted to select undergraduate students. Ever since Napoleon set up the baccalauréat, which is awarded by the education ministry, this exam has served not so much as a school-leaving diploma but as an entrance ticket to university, where tuition fees are negligible. Students can apply for any course they like, regardless of their ability. A centralised system allocates Mr Dardel’s students to his institution. This routinely overfills certain courses and causes overflowing lecture halls. When a university cannot take any more, those at schools nearby are supposed to be given priority, but such is the demand that places are increasingly being allocated through random selection by computer, known as tirage au sort, which this year affected 169 degree subjects across France. Ability is immaterial. “It’s an absurd distribution system which leads to failure,” says Mr Dardel. He calculates that the average dropout rate at Descartes over the past six years has been 45%.

Not all universities can be like 42. Mr Dardel admires the coding school but argues that there is still a place for theoretical maths in computer science. In year three, the computing degree at Descartes still puts a heavy emphasis on mathematical theory. Without the right to select those who attend, too many students fail, breeding disillusion and waste. In 2014, 81 of the 268 students allocated to the maths and computing course at Descartes did not have the bac “S”, the maths-heavy version of the school-leaving exam. After the first year as undergraduates, only two of those 81 passed their exams.

“We have a tendency in France to think you need a single solution for everyone,” says Mr Sadirac at 42. The lessons of his school, as well as of Descartes and Oran-Constantine, point a way for France to overcome the tyranny of normal in order to make more of what it does well and minimise what it does not. There is plenty of thinking about how to break free from standardisation and make teaching more individualised without losing excellence. France’s own world-class grandes écoles, its business and engineering colleges, which do well in international rankings, are highly selective, but they serve only about 8% of the student population. The challenge is to persuade public opinion, students, parents and teachers that variety, autonomy and experimentation are not a threat to equality but a means of restoring it to an education system that has lost sight of it. If Mr Macron can do this, he will have gone a long way towards improving the lot of people in places like the Calais housing estates whom the system currently fails.

Fuente: https://www.economist.com/news/special-report/21729614-time-more-variety-experimentation-and-creativity-one-kind-education-does-not-fit

Users Today : 156

Users Today : 156 Total Users : 35419335

Total Users : 35419335 Views Today : 176

Views Today : 176 Total views : 3353467

Total views : 3353467