América del Norte/Estados Unidos/02 de Julio de 2016/Autora: Tara García Mathewson/Fuente: Huffingtonpost

RESUMEN: La población de Bhután ha crecido hasta convertirse en un grupo floreciente, muy unido de cerca de 3.000 personas. Son parte de una población de refugiados sustancial desde el sur de Asia, África y Oriente Medio, que ha transformado la ciudad y sus escuelas. Los estudiantes en el Distrito Escolar de Syracuse hablan más de 70 idiomas diferentes y cuatro de los más comunes entre ellos son de Nepal, Karen, Somalia, y árabe. En 2010, para servir mejor a esta población, el Distrito Escolar de Syracuse creó una nueva posición – los trabajadores de nacionalidad – para servir como un puente entre las nuevas comunidades de inmigrantes y las escuelas. Dahal es uno de ellos, y una gran parte de su trabajo es la interpretación. Él ayuda a los padres inmigrantes comunican con los maestros de habla Inglés y los funcionarios del distrito y asegura que los padres tienen la oportunidad de ser escuchados.

SYRACUSE, N.Y. — When Dadhi Dahal first came to the United States in early 2009, the Bhutanese population in Syracuse, New York was quite small — the first refugees from Bhutan, fleeing ethnic cleansing policies in their home country, arrived in 2008, after they had spent years in refugee camps in Nepal.

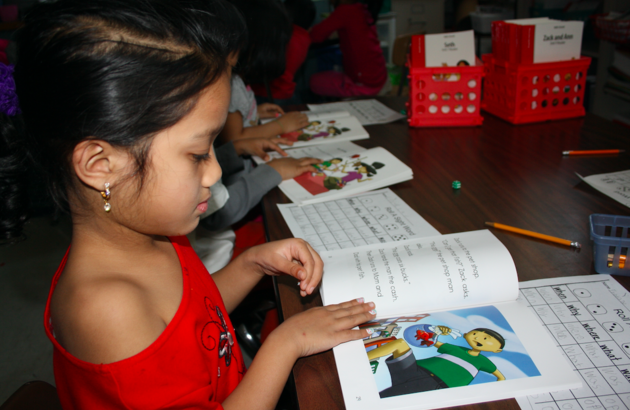

Fast forward eight years. The Bhutanese population has grown into a flourishing, tightly knit group of about 3,000 people. They are part of a substantial refugee population from South Asia, Africa and the Middle East that has transformed the city and its schools. Students in the Syracuse City School District speak more than 70 different languages and four of the most common among them are Nepali, Karen, Somali, and Arabic.

In 2010, to better serve this population, the Syracuse City school District created a new position — nationality workers — to serve as a bridge between new immigrant communities and the schools. Dahal is one of them, and a big part of his job is interpretation. He helps immigrant parents communicate with English-speaking teachers and district officials and ensures that parents have an opportunity to be heard.

The district, one of the poorest in the country, works hard to maintain open channels of communication with parents — because it’s important to student success, and because it’s the law. A failure to communicate effectively with immigrant parents is a violation of their civil rights, considered discrimination based on national origin, which is prohibited by the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Without language services, non-English-speaking parents are considered to be blocked from equal access to school information and resources.

As refugees spread out across the U.S., settling in the Southeast, Midwest, and many rural areas that, before, were fairly insulated from large immigrant populations, schools are being forced to adapt to a new reality. Syracuse is one of the more proactive districts when it comes to providing language access. While it struggles, at times, to meet its obligations, districts in other cities and states have fared worse. Dozens have been investigated by the Office of Civil Rights or the Department of Justice in recent years following complaints that they did not provide interpreters or translated materials to parents who needed them. These schools are in Yuma, Arizona; New Orleans, Louisiana; Richmond, Virginia; Detroit, Michigan; Modesto, California; and Seattle, Washington, among others.

“Providing an interpreter is a fundamental responsibility of a district when they have children or parents who do not speak English,” said Roger Rosenthal, executive director of the Migrant Legal Action Program in Washington, D.C.

Rosenthal has been advocating on behalf of immigrant families for more than 30 years, and he has been glad to see the Obama administration turn up the pressure on districts that don’t meet their obligations to them.

The legal rationale for language access requirements has existed for decades, but the Obama administration has been more aggressive than others in holding schools accountable. While the Civil Rights Act doesn’t specifically require schools to offer interpretation and translation services to parents — or any special supports for their non-English-speaking children – it bars discrimination based on national origin in any program or activity receiving federal dollars. The courts have consistently relied on this rationale to require schools to provide these services, and a “Dear Colleague” letter from the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights and the Department of Justice in 2015 went into explicit detail about what schools have to do to communicate with immigrant parents.

Providing an interpreter is a fundamental responsibility of a district when they have children or parents who do not speak English. Roger Rosenthal, executive director of the Migrant Legal Action Program

The letter says that schools must have a process in place to identify parents who need language assistance and assign the resources to provide it. They must ensure interpreters and translators are trained in their roles and understand the ethics and confidentiality requirements involved. And their services must be offered for free by competent staff members or contracted individuals.

Fuente: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/syracuse-schools-translator_us_5776b7cae4b04164640fe39b

Users Today : 104

Users Today : 104 Total Users : 35460010

Total Users : 35460010 Views Today : 152

Views Today : 152 Total views : 3418617

Total views : 3418617