‘It’s not enough to get students in the door’ — Reimagining the role of community colleges

Jamie Higginbotham has been involved in child care since she was 18 — first as a nanny, then the owner of an in-home child care business, and now the director of a preschool in Wilkesboro. Despite her 20-plus years in early education, she says she couldn’t support herself and her family on her wage alone.

“As a preschool director, my wage itself just with this one job, I would not be able to survive,” she said.

Higginbotham is a graduate of Wilkes Community College. She went back to school in 2016 to get her associate degree in early childhood education. This degree allowed her to move from preschool teacher to director, and she considers herself fortunate to be doing a job she loves. But still, she knows she and many of the teachers she hires wouldn’t be able to do this job if they were single parents.

“That is what is so disheartening,” she said, “because I know how cliché this sounds, but we are helping to raise our future.”

For years, community colleges have served students like Higginbotham who want to further their careers and better their lives. That doesn’t always happen, said Wilkes Community College President Jeff Cox.

“Getting a college credential only truly helps all the stakeholders in this ecosystem when institutions do a good job of preparing students for careers that are in demand and that will pay them wages high enough to support their families,” Cox said. “Too often, that’s not the case, even when educators and institutions have the best intentions.”

Spurred by economic mobility data and organizations like the Aspen Institute’s College Excellence Program, community colleges have begun rethinking their role in their communities.

“It’s not enough to get more students in the door. It’s not enough to graduate more students. We have to look at how many of them are getting jobs that pay a living wage,” said Cox.

In many cases, this is easier said than done. But, increasingly, it is a re-imagined role for community colleges that, if achieved, could help all North Carolinians.

How did we get here?

Community colleges in North Carolina and across the country have embraced their role as open-door institutions that increase college access.

“We’ve been so focused on access for so many years,” said Rachel Desmarais, president of Vance-Granville Community College. “And I think that’s been maybe a place we’ve been stuck. Presidents are thinking enrollment, enrollment, enrollment, and that really drives what colleges are doing.”

In 2009, the focus on access gave way to a focus on student completion as then-President Barack Obama announced the 2020 College Completion initiative with the goal of increasing the share of Americans with a college degree. At the same time, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded Completion By Design, a major reform initiative focused on increasing community college student completion rates. Five North Carolina community colleges participated in the initiative.

But these efforts, collectively known as the Completion Agenda, are not enough, said Josh Wyner, founder and executive director of Aspen Institute’s College Excellence Program.

“We are adherents to the Completion Agenda,” Wyner said. “We just think it’s incomplete.”

“If you’re going to give life to the idea of post-graduation success, colleges themselves need to own whether they are getting students credentials that deliver both economic and social mobility for the individual and the talent that’s needed in the community.”

Josh Wyner, founder and executive director of Aspen Institute’s College Excellence Program

The way to assess that, Wyner said, is to look at whether graduates are earning a family-sustaining wage.

This is far easier for colleges in North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park region, for example. In other parts of the state, including those that have lost textile and manufacturing industries over the past two decades, jobs that offer family-sustaining wages can be few and far between.

Despite the challenges, two North Carolina community colleges — Wilkes Community College and Vance-Granville Community College — are attempting to reinvent their role in their communities as drivers of economic mobility. Their journeys illustrate the challenges and opportunities in rethinking the role of community colleges.

Wilkes Community College

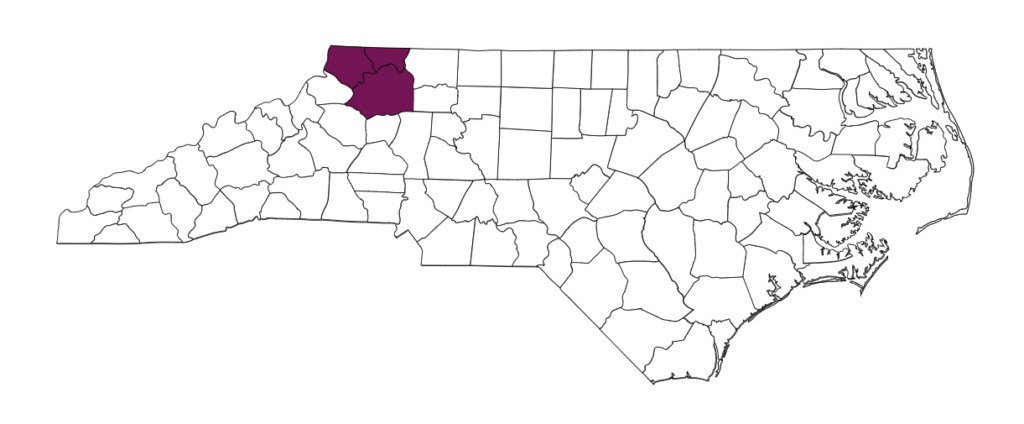

Wilkes Community College (WCC) is located in the northwestern corner of the state and serves Alleghany, Ashe, and Wilkes counties. In 2019-20, It served 8,966 students.

The median household income in WCC’s three-county service area ranges between $39,735 in Alleghany County to $44,080 in Wilkes County. Around one in three children live in poverty.

Once home to Lowe’s Home Improvement corporate headquarters, Wilkes County suffered the nation’s second worst drop in median household income from 2005 to 2015, according to Cox.

More concerning for Cox, however, was the lack of economic mobility in the area.

“If you’re born poor in northwestern North Carolina, there’s a two out of three chance you’re going to stay poor,” Cox said. “That just was alarming to me.”

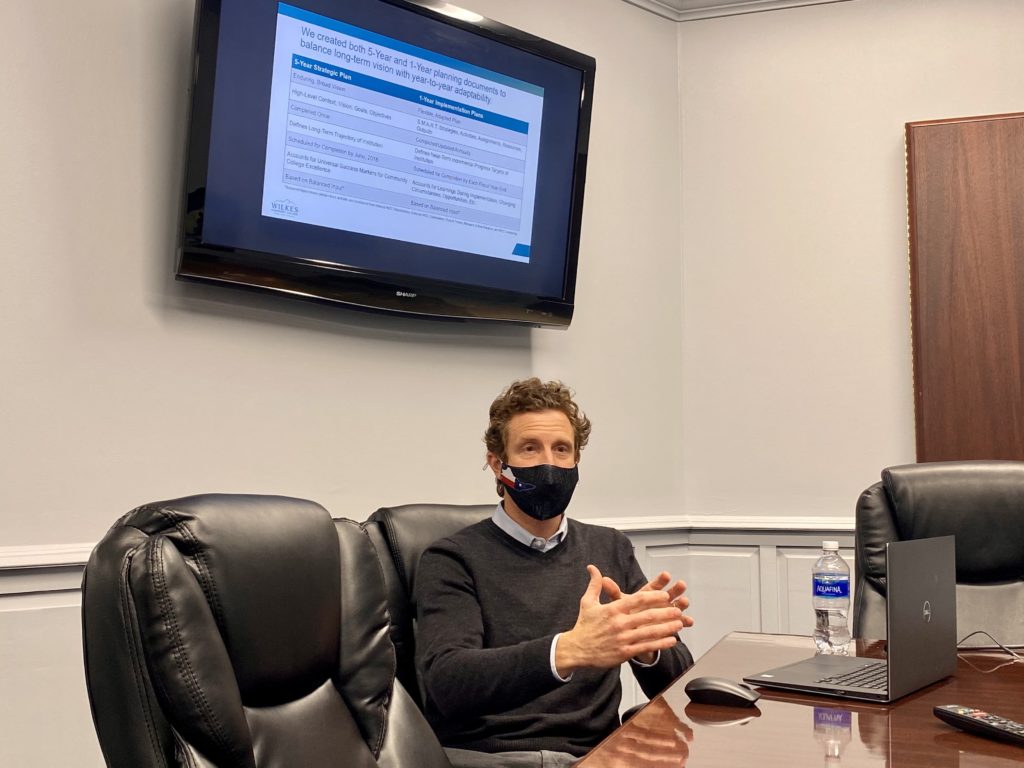

Having experienced the transformational power of education firsthand, Cox was determined to change that statistic when he became president in 2014. In 2017, the college started a strategic planning process, and Cox began orienting his faculty and staff around the importance of economic mobility.

“The question I put to our faculty and staff is, if it’s not up to the college to impact economic mobility of our students, then whose responsibility is that?” Cox said. “Who’s going to take on this cause if we don’t?”

To bring the message home, Cox did an exercise with his faculty and staff that he had learned at an Aspen Presidential Fellow. At the launch of their new strategic plan, he gathered his faculty and staff together and asked them to stand up and imagine they were the student body.

Cox divided them into four groups and sent them to different corners of the room. One by one, he asked each group to sit down as he went through groups of students who, for one reason or another, came to WCC but didn’t finish.

When he got to the last group, he asked half of them to sit down. The remaining 12.5% represented the students who graduated within three years and earned at least $10 an hour a year after graduating. Then he asked everyone to sit down except 10 people, or about 6-7%, who represented the students who graduated within three years and made $20 an hour or more.

He asked his faculty and staff to look around the room and tell him if they were satisfied with those numbers.

“That was a very stark reality check for our faculty and staff,” Cox said.

“We live sometimes off anecdotes. We have student success stories, but there are hundreds and hundreds more students who aren’t finishing at all or who are finishing but they’re finishing with degrees or credentials that are not helping them to go out and secure a better life when they graduate.”

Jeff Cox, president of Wilkes Community College

Cox and his team reached out to over 3,500 business, education, nonprofit, and community leaders in their region and produced a five-year strategic plan centered on “empowering more students with credentials that can provide a family-sustaining income while supporting regional workforce needs.”

Since the launch of that plan in 2018, and despite the COVID-19 pandemic, WCC has made progress on many of their goals, including boosting their completion rate and the share of associate degree graduates with the potential to earn the median household income of the area.

One strategy they say has been helpful in boosting their completion rate has been a completely revamped advising strategy.

“We knew we needed continuity from start to finish on the student journey,” said Zach Barricklow, vice president of strategy at WCC. “Not students being handed off from person to person to person because that’s how we lose them — they drop through the cracks.”

WCC formed a cross-functional team to study best practices in student advising. They reached out to dozens of colleges across the country who were doing advising well and interviewed them on what worked and lessons learned.

The team came up with a new model for advising where they pair each student with an instructor from their College Success Course, a course all new diploma or associate degree students are required to take. Then, they layer on a faculty mentor who has industry connections in the area in which the student is interested.

“By the end of it … [students] have at least two people at the college that they’ve developed really solid, deep relationships with,” Barricklow said.

To pay for this, WCC pitched the advising model to a family who wanted to make a donation. By using their College Success Course instructors as part-time advisors, they were able to turn a $1 million donation into funding for the advising model for 10 years. Not all colleges receive that type of philanthropic support, however.

Vance-Granville Community College

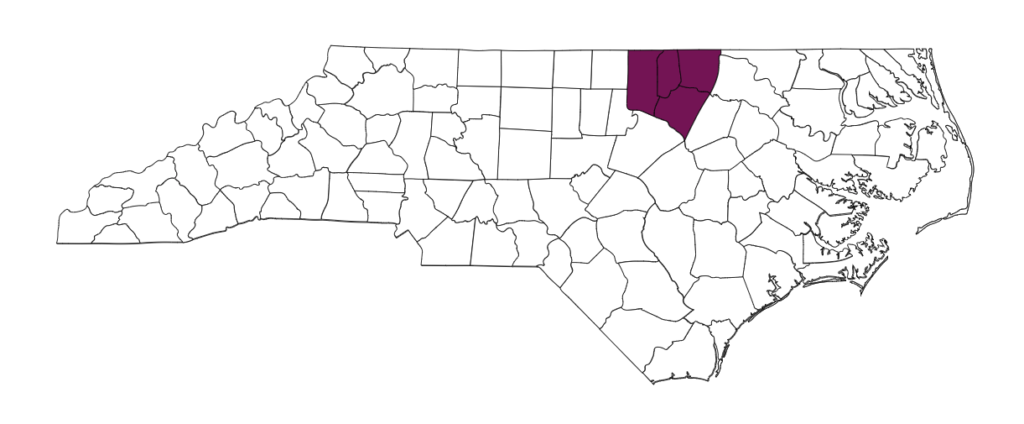

Vance-Granville Community College (VGCC) sits on the North Carolina-Virginia border, an hour north of Raleigh. It serves students in Franklin, Granville, Vance, and Warren counties. In 2019-20, VGCC served 9,396 students — a population that is about half white and half Black and Hispanic.

Two of its four counties, Vance and Warren, have median household incomes of $38,000-$40,000, whereas the other two, Franklin and Granville, are much higher at $57,710 and $58,956, respectively.

Rachel Desmarais, president of VGCC, started her role in 2019 after spending 16 years at Forsyth Technical Community College in Winston-Salem. It was during her time there that Desmarais came across Raj Chetty’s data on economic mobility.

“I was really struck because the area in which I lived was surprisingly really, really bad,” Desmarais said. “Winston-Salem/Forsyth County, in his initial calculation, was the third worst in the country for economic mobility … the only two communities that were worse in the United States in the original study were two reservations.”

“What I kept coming back to and seeing was there’s a population of people who keep getting left behind.”

Rachel Desmarais, president of Vance-Granville Community College

When she decided to apply to become a community college president, she looked for a school that would embrace the idea of economic mobility. She started at VGCC in January 2019, and one of the first things she did was commission a labor market analysis of their service area.

The analysis looked at job openings, hourly average wages, and industries where the area has an advantage compared to other regions and states. Desmarais and her team started reviewing their programs with this report in hand.

“We found it helpful looking at the openings and what we were producing and what that gap or surplus looked like and what the wage was,” Desmarais said. “The limitation of this report is it’s not going to tell you what’s on the horizon — it’s going to tell you what’s happening right now.”

Desmarais made the decision to close one of their cosmetology programs because she realized the return on investment for students was not there. Completion rates were low, she said, and wages were not good. In addition, there wasn’t enough market demand for the amount of students they were enrolling.

In response to some pushback on this decision, Desmarais asked her faculty to look at why completion rates were so low in the cosmetology programs.

“And it came back, well, they don’t really need the whole two years,” she said. Her response: “Oh, okay, let’s start there and change the way we’re advising.”

Challenges of aligning programs with high wage jobs in rural areas

Durham Technical Community College is in the beginning stages of making this shift from focusing on access and completion to focusing on economic mobility.

“Coming out of COVID, we’re recognizing … there are programs of study, which we could get folks to complete, which wouldn’t particularly bring them to a better place in terms of economic opportunity and certainly in terms of family-supporting wages,” said Durham Tech President J.B. Buxton, who started his role in 2020.

Following in WCC’s and VGCC’s footsteps, Durham Tech is undertaking a strategic planning process and evaluating each program from the lens of economic mobility. And while they may be shifting resources away from programs like cosmetology that do not offer family-supporting wages to students, that’s where the comparison ends.

Unlike WCC and VGCC, Durham Tech is sitting in one of the hottest labor markets in the country for certain sectors, Buxton said. His job is to figure out how his students can get jobs in life sciences, healthcare, and IT that don’t require a four-year degree and pay a family-sustaining wage.

It’s a different story in rural areas where there just aren’t enough jobs that pay living wages. That creates an “export education business,” said Barricklow.

“We know that our local labor market is limited,” he said. “Even our commutable labor market is limited in terms of living wage options. And so what does that do? That creates an export education business. We educate our young folks, and then we export them to Raleigh and Charlotte and elsewhere for opportunity.”

Community colleges in North Carolina have been involved in economic development since their founding, but the increasing concentration of economic opportunities in the metropolitan areas of the state leave rural colleges searching for answers.

Wyner said there are three main strategies community colleges can take when they are looking to build economic mobility in regions with few opportunities.

Bargaining power

The first is to use their bargaining power to encourage employers to increase wages. Cox said he encourages businesses to provide a more competitive wage if they cannot find employees, but there’s only so much he can do.

If employers won’t consider a living wage, Wyner said, colleges should stop offering to train their employees.

“At some point you have to say no,” Wyner said. “At some point you have to say, ‘Look, if you’re not going to offer more than a high school diploma in terms of wages, I’m not going to deliver this credential to you.’ It’s not worth it to my students, and it’s not worth it to the public and the taxpayer to deliver something to them that doesn’t give them a decent life.”

Another option is to pair training with business courses, so cosmetology and culinary students, for example, can start their own businesses.

Refusing to offer training for low-wage occupations is not always the answer, however. Training early childhood educators is one example of something community colleges are not going to stop doing despite the low wages of early childhood educators.

Instead, Desmarais and Cox emphasized the importance of talking to early education students about wages and future pathways for career advancement, such as getting a four-year degree and moving into the K-12 space.

“We need early childhood workers, so we don’t want to disband that program,” Cox said. “But we do want to be honest with students … If you want to get up to where you’re making a living wage, then you need to be thinking about something beyond this two-year associate degree. If you get a four-year degree, you can teach in the public schools and you can make a living wage in that job. If you don’t, in that particular program, you’re going to struggle economically.”

WCC early childhood lead instructor Melissa Miller said the hardest day at her job was the day the local Burger King put up a sign saying, “Now hiring starting $9.50 an hour.” Miller had just been talking about salary with her students, which for an entry-level early childhood job is about $8 an hour, she said.

At Durham Tech, Buxton said he is lucky to have a county commission that is committed to paying early childhood workers at the same level as elementary school teachers.

“That means that’s clearly a place that we can feel good about staying engaged,” he said.

Regional partnerships

The second strategy, Wyner said, is to pursue regional partnerships. Many rural areas have shortages of teachers, accountants, and public safety jobs, Wyner said, almost all of which require a bachelor’s degree.

“If your community has good jobs in those areas and you’ve got students coming to community colleges, they probably want to stick around, and you need to figure out how to partner with a four-year school,” he said.

Many such partnerships exist in North Carolina. The community college system has universal articulation agreements with both the UNC System and North Carolina’s Independent Colleges and Universities to help students transfer smoothly. Many schools also have bilateral articulation agreements with specific four-year colleges in their region.

The approval of teacher preparation programs at community colleges over the past year will also provide a pathway to good jobs for community college students who want to stay in the area and teach.

In addition to partnerships with universities, community colleges should also look at regional partnerships with industry, Wyner said.

“Find the nearest community that has jobs and figure out how to partner to deliver jobs to those folks,” he said. “You have to keep expanding the concentric circles to see where those jobs might be.”

In North Carolina, community colleges are somewhat constrained by rules mandating that they stay within their service area when looking at industry partnerships, Desmarais said. However, they can find ways to partner with other community colleges that cannot meet the needs in their service areas.

“There is no way that [Durham Tech] can meet all the biotech needs and bioprocessing needs,” Desmarais said, “and so I’m kind of secondhand because the companies actually reside in his service area. [We] have to be invited to the table.”

Desmarais said she’s having conversations with Buxton and other presidents to explore new ways of working together regionally.

A vision for the future

The third strategy, the “most developed idea” according to Wyner, is to actually develop a new economy. He gave the example of Walla Walla Community College in Washington state that developed a wind energy program that attracted employers to the area.

“What Walla Walla did was they looked to the future. They did an economic analysis, and then they talked to people,” Wyner said. “They had a vision for the future.”

Cox and Desmarais both have a vision for the future that draws upon the assets of their respective regions.

For Desmarais and her team, their location combined with the relatively cheap cost of land present an opportunity to draw companies that need easy access to transportation and space for warehouses. VGCC is located one hour north of Raleigh and sits on a major highway, I-85, that runs from Montgomery, Alabama to Richmond, Virginia.

“Everyone knows that Wake County is expensive and out of land,” Desmarais said. “I think the counties just south of Wake have been doing a really good job of pulling industry down that way. With I-85, we have a really unique opportunity to pull it up as well.”

Desmarais is also looking to the past. With their proximity to North Carolina State University, an agricultural technology powerhouse, Desmarais sees potential in agriculture.

“This used to be an area of rich agricultural tradition,” she said, “and so we’re looking at bringing that back in, and what’s the community college’s role in that.”

Cox and his team have landed on a somewhat unconventional strategy — and one that has only become more salient with the pandemic.

As they looked at their ability to create economic opportunity in their region, they didn’t see much potential to draw significantly more manufacturing to the area.

“In Alleghany you would literally have to move a mountain in order to get a flat enough site in order to build a facility,” Barricklow said. “And then you have to convince folks it’s worth driving those windy roads up and back to get a product in and out. It’s just not well suited for it.”

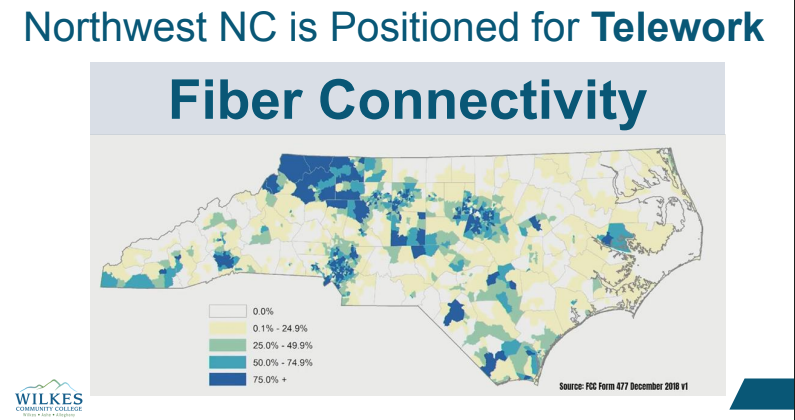

Instead, they looked at what they did have — an abundance of natural beauty and world-class fiber connectivity. Capitalizing on these two assets, WCC decided to pitch northwest North Carolina as a telework destination.

“Industrial recruitment, on some level, will always be part of the economic development equation,” Cox said. “But instead of just trying to attract business or industry to create manufacturing jobs, we shifted our focus to telework: preparing and connecting local folks with good-paying remote jobs with employers that may be located elsewhere, as well as attracting individuals to our region who can bring their remote work with them.”

They presented this strategy before the pandemic and received some interest, Cox said. Then, COVID-19 hit.

“What we thought might take us years to convince people that you could do this in a more comprehensive way, and you could telework — of course instantly a month later virtually the whole world was teleworking,” Cox said.

Cox and Barricklow have come up with a plan that includes strategic partnerships with organizations specializing in remote worker training and job placement in the tech industry, among others. They are currently applying for funding to get the effort off the ground.

“We live in a beautiful part of the world, where I’m convinced a lot of people that are in RTP would rather live here and bring their jobs if they could do it from here,” Cox said.

What comes next?

The next layer in this work, Desmarais said, is to look at their programs through an equity lens as well as an economic mobility lens.

“If I see a program that is heavily white male, then I need to ask myself why is that? Why is there not diversity?” she said. “Likewise if I see a program that is very Black female, why is that, and what are the earnings of these programs?”

Wyner agreed. “We know there are deep inequities in not just who gets a degree, but which degrees people get and whether those degrees have value,” he said. “If we don’t pay attention by race and ethnicity and Pell status, we can’t make good on the promise on equity in higher education either.”

Both VGCC and WCC are also thinking about the impact of the pandemic on labor markets and job opportunities for their students.

Cox is hoping telework is here to stay, and WCC is able to draw people to the area who wouldn’t otherwise be able to move there as well as connect students to outside opportunities.

“I’m hoping [the pandemic] makes us more flexible,” Desmarais said. “I’m determined it will make us think outside the box and offer supports so we can enable people to get what they need. We’ve got to get darn good at not letting people wander around.”

This story was produced as part of the Higher Education Media Fellowship. The fellowship supports new reporting into issues related to postsecondary career and technical education. It is administered by the Institute for Citizens & Scholars and funded by the ECMC foundation.

‘It’s not enough to get students in the door’ — Reimagining the role of community colleges

Users Today : 12

Users Today : 12 Total Users : 35459607

Total Users : 35459607 Views Today : 32

Views Today : 32 Total views : 3418005

Total views : 3418005