By Ma. Dolores Gallegos Ávila, ASFG Spanish teacher and MS Curriculum Specialist, Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico

According to the 6th National Communication in 2018, efforts in Mexico to promote education and public awareness of climate change are based on the international legal framework and the national education policy. This blog post shows what my school is doing to realize this imperative.

What is the point of denying what is evident? Both the extreme heat with the severe droughts and forest fires that affect crops and livestock in the dry season as well as the low temperatures with cold fronts and icy waves in autumn and winter, are challenging meteorological phenomena. Even floods or the devastating hurricane Otis in Acapulco in October 2023, which left chaos and pain, are symptoms of something bigger calling for our attention. The imperative for us teachers is to promote a high-quality climate change education that includes learning to be (socio-emotional), to know (cognitive), to do (action-oriented), and to live together (justice-focused). This will empower students with knowledge, skills, values, habits and tools that help them be more resilient, responsive and compassionate, so they can see the future with hope.

As part of the American School Foundation of Guadalajara in Mexico and as grade 8 Spanish teacher and Spanish curriculum specialist in lower secondary school, I am constantly looking for relevant topics to link climate issues into what I teach in order to create meaningful experiences for students.

I decided to try something new, linking the grade 8 Mexican Spanish curriculum and climate change. From December to January this year, 71 students in my class worked on a political cartoons project. The goal was to create an awareness campaign about climate change, transforming some recent local, national or world news, chosen by them, into political cartoons. The challenge was to select them after consulting different sources, analysing the information to get more width and depth and find a connection between their topic and climate change. They had to define their standpoint, look for a better and creative way to visually synthesise what they wanted to communicate, which had to be humorous. They also had to use at least one of six cartoon rhetorical figures that we saw in class. They knew from the very beginning that they were contributing to an awareness campaign about climate change and that, at the end of the project, they were going to visit other classes to generate dialogue and inspire new actions.

Just as the GEM Report and the MECCE project are collecting data worldwide on the extent of green coverage in education content in curricula and syllabi, my school is currently assessing internally who is embedding what about climate change into the curriculum and how.

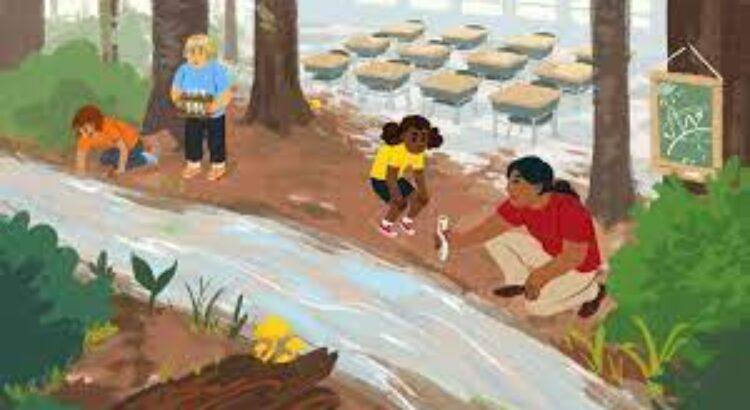

In early childhood, we found that efforts tend to work on sensitizing young students to experience love and connection to nature through observing, listening, planting, harvesting or exploring. In primary school, students learn how things are happening, without creating panic, they learn to love nature (‘a ha’ experiences) and about the fact that all our actions have impacts. In lower secondary school, they learn more science, how and why things happen and try to find innovative solutions. In upper secondary school, students are confronted with ethical choices linked to reality: to me and the collective.

As an adult, it is time to bring all these abilities together to stand for climate smart actions. Examples of this are the school garden promoting outdoor activities or the Green Committee consolidating events like the Earth Day celebration. This opens new options to be more conscious about why it is so important to implement sustainability education in our school.

The most significant aspect of this emergent movement is the dynamic generated by the collaboration among all parts of the community: teachers, students, parents, administrators, staff and external institutions. It is like a web that is constantly interweaving and increasing its sphere of influence, depending on the thoughts, feelings, intentions and decisions of people in all levels, focused on common goals. Each time that we find new connections, we become more aware of our role to actively generate positive change. Every colleague who is creating innovative learning situations in class using different approaches or cross-cutting topics (critical thinking, systems thinking, sustainable habits of mind, Sustainable Development Goals, climate change, social and emotional learning, science, technology, engineering, art and mathematics etc.) is contributing to modifying limiting mental models in our society and reshaping the future.

It is our collective responsibility getting schools ready to tackle climate change without delay!

The post Climate change education matters: what’s the point of denying what is evident? appeared first on World Education Blog.

Users Today : 256

Users Today : 256 Total Users : 35459851

Total Users : 35459851 Views Today : 429

Views Today : 429 Total views : 3418401

Total views : 3418401