By: Robert Bridge

Critics of lockdowns & school closures to halt Covid-19 have compared the effects to child abuse. And now that new data points to some deeply disturbing long-term psychological damage, it looks like they were right.

Abiding by the new age medical maxim that commands ‘everyone stop living so that you don’t die’ is no way to live. Yet that is exactly how millions of youngsters have been forced to cope with a disease that poses, in the overwhelming majority of cases, no more of a health risk to them than riding a bicycle or crossing an intersection.

And while socially isolating the youth may have spared a minuscule fraction from contracting coronavirus, the total impact such measures have had on the mental wellbeing of this demographic has been a disastrous tradeoff.

The results from the most inhumane experiment ever conducted on human beings are in, and we should all be ashamed of ourselves for letting it happen.

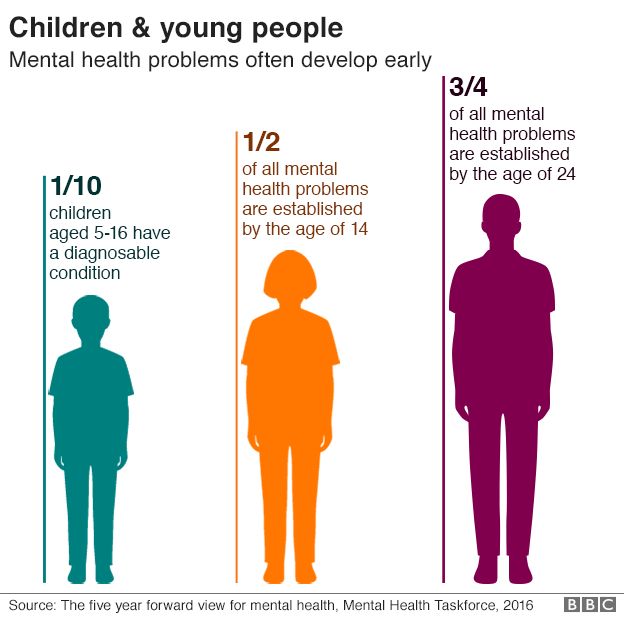

In a white paper published by the nonprofit FAIR Health, the consequences of lockdowns on the mental health of American students reveal what many people already know: “School closures, having to learn remotely and isolating from friends due to social distancing have been sources of stress and loneliness.” The real shocker, however, is how that statement plays out in real life. In March and April 2020, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, mental health claims among this young demographic exploded 97.0 percent and 103.5 percent, respectively, compared to the same months in 2019.

To break it down even further, there was a dramatic surge in cases involving “intentional self-harm” using a handgun, sharp object and even smashing a vehicle, as the more popular examples. The rate of incidence for such destructive behaviors amid 13-18 year olds jumped 90.71 percent in March 2020 compared to March 2019. The increase was even greater when comparing April 2020 to April 2019, almost doubling (99.83 percent). August 2020 was particularly active in the northeast sector of the country, showing a surge of 333.93 percent.

Similarly major increases were found among the 19-22 age category, although not quite as pronounced as the 13-18 group.

Another sign that young Americans have suffered undue psychological distress during the pandemic is observable from the rate of overdoses and substance abuse. For those between the ages of 13-18, overdoses increased 94.91 percent in March 2020 and 119.31 percent in April 2020 over the same periods the year before. Meanwhile, substance use disorders surged in March (64.64 percent) and April (62.69 percent) 2020, compared to 2019.

In one sample taken of the 6-12 age groups, increases in obsessive compulsive disorder shot up in March 2020 (up 26.8 percent) and persisted through November (6.7 percent). At the same time, nervous tic disorder increased some 28.7 percent by November. Another trend worth mentioning is that before the pandemic began, females in the 13-18 group accounted for 66 percent of total mental health claims; from March 2020 onward, the percentage increased to 71 percent in females compared to 29 percent in males.

The findings by FAIR are supported by other prominent studies, including one by the American Academy of Pediatrics, which found higher rates of suicide attempts in February, March, April, and July 2020 compared with the same months in 2019.

The unconscionable part of this tragedy is that children are known to be amazingly resilient to coronavirus. According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, the “majority of children do not develop symptoms when infected with the virus, or they develop a very mild form of the disease.” And among their peers at school, “outbreaks have not been a prominent feature in the COVID-19 pandemic.”

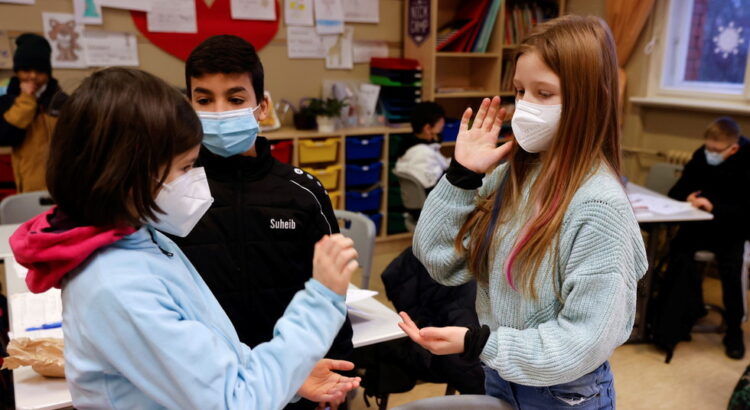

At the same time, scientific studies have proven that children are not Covid-19 “super spreaders,” which means that their teachers would be at low risk of infection. In other words, there is absolutely no reason that children should not be back in school, studying and socializing side-by-side their friends in a supportive, learning atmosphere.

Some places in the United States have begun to see the light. The Republican-run states of Arkansas, Florida, South Dakota and, most recently, Texas, encouraged by dropping infection rates and a nationwide push for vaccines, have fully reopened businesses and schools.

President Joe Biden, however, betrayed the severe political brinkmanship lurking behind Covid-19 when he slammed the decisions as “Neanderthal thinking.” In any case, while the gradual opening of America is a welcoming sign of much-needed sanity, it seems the damage has already been done as far as the mental condition of its youth are concerned. In fact, I find the consequences on par with that of the trauma experienced during war, and in some ways even worse. Not least that this was self-inflicted.

Covid-19, or rather our responses to it, have had all of the destructive force of a hydrogen bomb – albeit a silent one – dropped smack in the middle of our communities and sucking out the precious life. Now entire families are forced to ‘shelter in place’ from an enemy they cannot see, while businesses, schools and even churches – the essential meeting places that give people hope and strength – have been forced to close their doors.

Children have been taught to look at each other warily, like walking chemical factories capable of infecting and even killing, as opposed to fellow human beings that can provide love, comfort and support. It is my opinion here that the medical authorities who imposed this protracted lockdown on the youth have forfeited the right to practice medicine ever again – and a similar fate should await the politicians who sanctioned it.

Let’s be clear. We are not talking about the Black Plague of the 14th century, where entire towns were wiped out and bodies piled up in the streets as people fled to the remote villages and countryside to escape certain death. Not by a long shot. Yes, it is important to take precautions against this virus, but catching Covid is not a death sentence; an estimated 99.75 percent of those infected can expect to fully recover, while the incidences of children dying from coronavirus are exceedingly rare.

In the overwhelming majority of cases, those who do succumb to Covid are the elderly who had already been weakened with “comorbidities.” While every death is regrettable, the sort of fatalities we are dealing with do not justify the lockdown of Main Street, to say nothing about businesses, churches and schools. It would have been far more humane had the elderly and sick been singled out for special protection, while the rest of the world got on with the business of living.

Instead, we did the most unconscionable thing imaginable, forcing young children – at the most momentous times of their lives – to adhere to social distancing rules while shutting down their schools and imprisoning them in their homes. That is simply cruel and unusual punishment. In a word, it is child abuse. We failed to heed the warning about where that allegorical road paved in “good intentions” may lead us, and that is exactly where millions of children now find themselves. Trapped in a mental hell of the adult world’s making. I pray that, one day, they forgive us.

Source and Image: https://www.rt.com/op-ed/517823-kids-forgive-covid-lockdown/

Users Today : 2

Users Today : 2 Total Users : 35460211

Total Users : 35460211 Views Today : 3

Views Today : 3 Total views : 3418898

Total views : 3418898