África/Noviembre de 2017/Autor: Steve Johnson/Fuente: Financial Times

Resumen: África se ha convertido en un continente menos seguro y respetuoso de la ley en la última década, según una encuesta influyente.

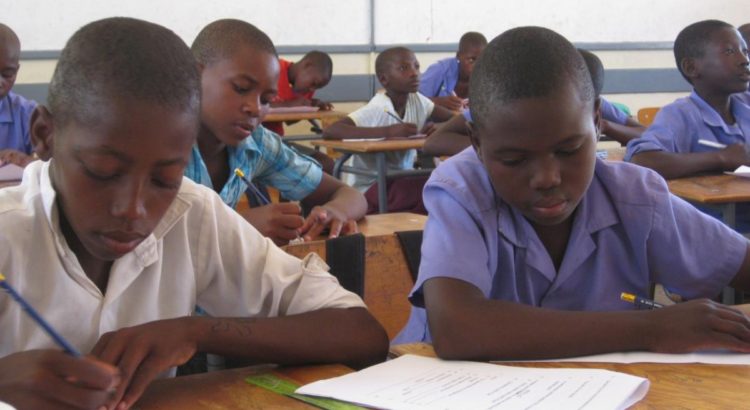

El Índice anual de Gobernabilidad Africana de la Fundación Mo Ibrahim también advierte sobre la desaceleración del progreso en educación en un continente donde el 41 por ciento de la población tiene menos de 15 años, y el deterioro de las perspectivas para aquellos que viven en áreas rurales.

Mo Ibrahim, un multimillonario de telecomunicaciones sudanés-británico, temía que los sistemas educativos que no están capacitando a los alumnos para el trabajo corrían el riesgo de alimentar la violencia.

«Jóvenes, desempleados, sin esperanza, ¿qué van a hacer? Ellos intentarán este viaje a través del Sahara, al otro lado del Mediterráneo, enfrentando la muerte en el desierto o en el mar, o entrarán en estos grupos terroristas que pueden proporcionar algún tipo de ingreso, alguna forma de redención y respeto propio «, dijo. «Es una situación peligrosa con consecuencias peligrosas».

Africa has become a less safe and law-abiding continent in the past decade, according to an influential survey. The Mo Ibrahim Foundation’s annual Index of African Governance also warns of slowing progress in education in a continent where 41 per cent of the population is under 15, and deteriorating prospects for those living in rural areas. Mo Ibrahim, a Sudanese-British telecoms billionaire, feared that education systems that are failing to equip pupils for work risked fuelling violence. “Young people, unemployed, no hope, what will they do? They will try this trek across the Sahara, across the Mediterranean, facing death either in the desert or in the sea, or get into these terrorist groups that can provide some form of income, some form of redemption and self respect,” he said. “It’s a dangerous situation with dangerous consequences.” The overall measure of governance in Africa’s 54 states, based on 100 indicators, ticked up to 50.8 in 2016, on a scale of 0 to 100, after flatlining since 2010. However Mr Ibrahim warned that the pace of progress has slowed in the past five years compared to the previous five. “The slowing, and in some cases, even reversing progress in a large number of countries, or in some key dimensions of governance, is worrying for the future of the continent,” he said. Three of the four pillars that feed into the overall index: human development; sustainable economic opportunity; and participation and human rights, have improved over both five and 10 years, albeit at a slowing pace. However the fourth pillar, safety and the rule of law, has deteriorated over both time periods, as the first chart shows. In particular, the index flags up worsening social unrest, armed conflict, human trafficking, personal safety, crime and corruption. Share this graphic Troubled states such as South Sudan, Burundi and Libya have experienced the sharpest deterioration in the past decade, followed by the likes of Egypt, Mozambique and Cameroon. Charles Robertson, chief economist at Renaissance Capital, an emerging market-focused investment bank, cited “constant terrorism concerns in Egypt and Kenya, mutinies in Ivory Coast and unrest in Addis Ababa,” while South Sudan was “degenerating” and “crime remains a problem in South Africa”. The failure to establish the rule of law in Libya, meanwhile, has created a lucrative opportunity for human traffickers across the region, Mr Robertson said. There have been some positives though, such as Nigeria’s success in curbing Boko Haram, an Islamist group. Share this graphic Mr Robertson attributed many problems to weaker commodity prices, which have damaged government finances. This saps many countries’ ability to keep a lid on economic and social problems given that “in low per capita GDP countries conflict and disruption is more common”. The index’s human development measure, which includes health and welfare, has risen solidly, despite sharp slides in Libya and Ghana. However the education component of this has stalled. Share this graphic Mr Robertson, who has written extensively on the link between education and economic growth, said that while primary school enrolment and literacy rates were improving, he shared Mr Ibrahim’s concerns about the quality of education in some countries. “Malawi has gone from 75 children per class in 2000 to 126. How can they teach and learn much?” he said. Share this graphic Mr Ibrahim’s other major concern centred on opportunities in rural areas, which his index suggests have worsened since 2009-13. “Agriculture is the mainstream of the African economy. We have half our population living on the land and off the land,” he said. “We need to work this land and improve productivity. How can we make agriculture more sexy so young people want to do it? How can we increase the income of smallholders?” At the country level, Ethiopia is one of a quartet where overall economic opportunities are deteriorating at an accelerating pace, despite its high-profile, largely Chinese-funded attempt to copy Beijing’s development model. Share this graphic And, while most countries with “increasing deterioration” at headline level have the excuse of ongoing crises, Mr Ibrahim raised red flags over the direction of travel in Botswana and Ghana, even if they still remain among the best governed countries. One apparent success story, however, is Zimbabwe. Despite only being ranked 40th out of 54 countries, it has made among the biggest advances over the past five years. Significant improvements have been realised in economic development, human rights, security and the rule of law — at least before last week’s attempt to topple President Robert Mugabe. Mr Ibrahim was equivocal about the military intervention: “I’m not excited at all. This is a quarrel between factions in the ruling party, some wearing uniforms and some not, so what difference does it make? It’s the same generation. It’s not like we have a Mandela coming out of prison to take over.”

Fuente: https://www.ft.com/content/23c5d21a-cacb-11e7-aa33-c63fdc9b8c6c

Users Today : 88

Users Today : 88 Total Users : 35459994

Total Users : 35459994 Views Today : 124

Views Today : 124 Total views : 3418589

Total views : 3418589