Guatemala/07 de Agosto de 2017/WRadio

Los indígenas de Guatemala, casi la mitad de la población, continúan hoy enfrentando una discriminación social y económica arraigada en la sociedad y en las políticas públicas del Estado, por lo que es necesario hacer una «reflexión colectiva» para cambiar esta situación.

Los indígenas de Guatemala, casi la mitad de la población, continúan hoy enfrentando una discriminación social y económica arraigada en la sociedad y en las políticas públicas del Estado, por lo que es necesario hacer una «reflexión colectiva» para cambiar esta situación.

Esta es una de las principales conclusiones de un análisis hecho hoy en Ciudad de Guatemala sobre la situación de este colectivo, en el que participaron miembros de la ONU, de la Defensoría de la Mujer Indígena, la Comisión Presidencial Contra la Discriminación y el Racismo, entre otros.

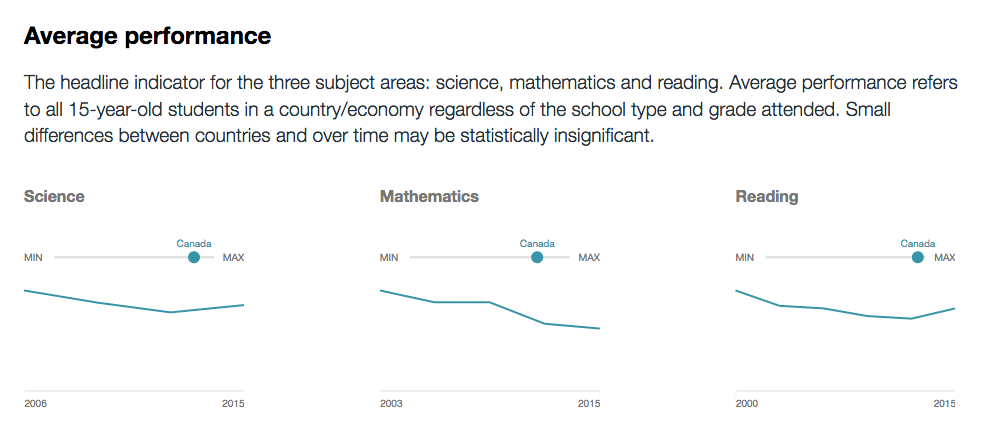

El representante en Guatemala de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura (FAO), Diego Recalde, destacó que en el país, al igual que en el mundo, aún persisten «grandes desafíos» para hacer efectivos los derechos de los pueblos originarios, como la justicia, la salud, la educación, la alimentación, el derecho a la tierra o el trabajo.

«Hay que lugar contra el racismo y la discriminación arraigada» en la sociedad guatemalteca, enfatizó Recalde, y señaló que esta situación particular «de alta vulnerabilidad» de los pueblos indígenas es un problema mundial que requiere «redoblar» los esfuerzos para ponerle fin.

«La sociedad guatemalteca tiene esa oportunidad de cambiar estas cifras tan lamentables», señaló al recordar que la desnutrición crónica afecta a más del 70 % de los niños menores de 5 años en el occidente del país, cuando el promedio es de 56, o la falta de acceso a educación y salud.

Es por ello que abogó por promover nuevos modelos de desarrollo, con un enfoque de derechos humanos y desde el aspecto inclusivo e incluyente, máxime ahora que se cumple el décimo aniversario de la proclamación de la declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre los derechos de los pueblos indígenas.

Guatemala, que celebrará la próxima semana el Día Internacional de los Pueblos Indígenas con diversas actividades, es un país multicultural y plurilingüe compuesto de cuatro grandes culturas: Maya, Xinca, Garífuna y ladina, y en su territorio conviven 25 comunidades lingüísticas.

Según datos facilitados por Naciones Unidas, se calcula que en la actualidad existen unos 370 millones de personas de diferentes comunidades indígenas repartidos por noventa países alrededor del mundo.

En Guatemala, el porcentaje de la población indígena es de un 41 %.

Entre los departamentos de Guatemala con mayor porcentaje de población indígena figuran Totonicapán (98,3 %), Sololá (96,4 %), Alta Verapaz (92,9 %), Quiché (88,8 %), Chimaltenango (79 %) y Huehuetenango (65,1 %).

De la inversión pública total, Guatemala dirige hacia los pueblos indígenas tres veces menos que a la destinada a la población no indígena, un hecho que no hace más que aumentar la brecha y la discriminación racial económica.

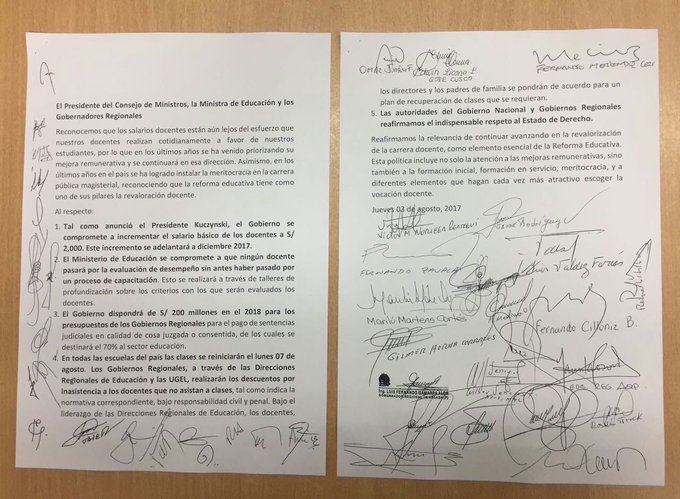

Según un estudio divulgado recientemente por el Instituto Centroamericano de Estudios Fiscales (Icefi), por cada quetzal (14 centavos de dólar) invertido en los pueblos no originarios, el Estado tan solo destina 33 centavos (4 centavos de dólar) a los pueblos indígenas.

El análisis, realizado sobre el presupuesto de gasto público de Guatemala ejecutado durante 2015, identifica que del total dirigido al ciudadano, 42.623 millones de quetzales (5.818 millones de dólares), solo la cuarta parte se destinó a los pueblos indígenas, 10.646 millones de quetzales (1.453 millones de dólares).

Estas cifras dejan entrever que las inversiones dirigidas a la población no indígena (mestiza o ladina) representaron un 6,5 % del producto interno bruto (PIB), en contraposición al 2,2 % de los pueblos originarios.

Fuente: http://www.wradio.com.co/noticias/internacional/indigenas-de-guatemala-ante-una-discriminacion-social-y-economica-arraigada/20170803/nota/3539144.aspx

Users Today : 3

Users Today : 3 Total Users : 35474750

Total Users : 35474750 Views Today : 5

Views Today : 5 Total views : 3574798

Total views : 3574798