Africa/ Nigeria/ 29.10.2019/ Fuente: www.sierraclub.org.

I will hammer with one hammer!

I will hammer with one hammer!

All day long!

All day long!

THE CALL-AND-RESPONSE IS ENTHUSIASTIC, rising above the sound of a fan whirring furiously in the corner of the room. About 50 women stand in a circle around the song leader, who pounds the air with an invisible hammer. When she gets to the second verse—»I will hammer with two hammers!»—she pumps both arms up and down, and the rest of the women follow. By the fourth verse, their feet have joined in, stomping the ground, and by the fifth, everyone is bobbing their head up and down too. As the song ends, the room erupts in laughter.

It’s a typical day at the Center for Girls’ Education. On this hot, breezeless afternoon in May, in the third week of Ramadan, most of the women are fasting, but their infectious energy gives no hint of this.

The Center for Girls’ Education (CGE) is located in a plain, single-story building on the campus of Ahmadu Bello University, in the northern Nigerian city of Zaria. Its offices are sparse: a big table, a few desks, a couple of computers. For large meetings, everyone sits on mats on the floor. The concrete walls are bare, save for sheets of paper scrawled with motivational messages like «Work Hard, Have Fun, Make a Difference.»

The purpose of today’s meeting is to give some visitors an overview of the organization, and it began with the center’s director, Habiba Mohammed, leading the staff in a «love clap» to make the visitors feel welcome: «[clap clap] Mmm, [clap clap] mmm, [clap clap] mmm, [clap clap] we love you.» Then staff members take turns introducing themselves. When it’s her turn, Mohammed says, «One thing I want you to remember about me is that I am still a girl.»

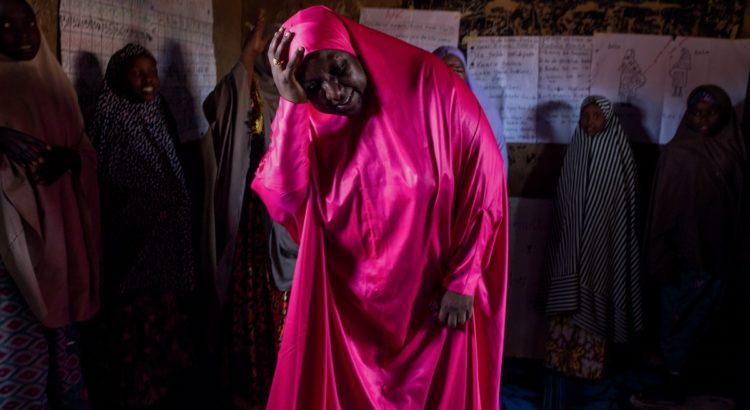

CENTER FOR GIRLS’ EDUCATION DIRECTOR HABIBA MOHAMMED ACTS OUT LABOR PAINS DURING A REVIEW OF REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH.

CENTER FOR GIRLS’ EDUCATION DIRECTOR HABIBA MOHAMMED ACTS OUT LABOR PAINS DURING A REVIEW OF REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH.

At 50, Mohammed isn’t exactly a girl, but with her friendly, open smile and generous laugh, she exudes youthful energy. Her statement seems meant to convey how closely she identifies with the girls CGE serves.

Over the past decade, CGE has helped thousands of impoverished adolescents in northern Nigeria stay in school or gain the skills they need to enroll. A joint program of the School of Public Health at UC Berkeley and the Population and Reproductive Health Initiative at Ahmadu Bello University, the center operates seven projects made possible by funding from institutions including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and the Malala Fund. Thanks to such philanthropy, the center is growing fast. In 2016, its Pathways to Choice project expanded beyond Kaduna State into two other northern states. Another project, the Adolescent Girls Initiative, aims to reach 30,000 girls in at least three more states by the end of the year through a partnership with the United Nations Population Fund.

«In Nigeria, we have 10.5 million out-of-school children,» Mohammed says. «We are always hoping to help whoever wants to support girls, wherever that person is, even if we have to climb mountains or swim oceans.»

Since its inception, the Center for Girls’ Education has grown to a staff of about 70—nearly all of them Nigerian women, the majority of them Muslim, enabling the organization to fluently navigate northern Nigeria’s culturally conservative, mostly Muslim, rural villages to promote girls’ education. The organization’s local connections have allowed it to shift cultural norms without violating them as it advances the health and well-being of women and girls, and by extension entire communities.

«When a girl has an education, she will make a better person in her home, in the community, and everywhere she finds herself.»

The center’s success has broader implications too, as climate change starts to bear down on one of the world’s most populous nations. A large body of research confirms that when girls are educated, their families and communities are more resilient in the face of weather-related disasters and better able to adapt to the effects of climate change. Educated women have more economic resources, their agricultural plots reap higher yields, and their families are better nourished.

Staff members don’t tend to think about their efforts through the lens of climate change; nevertheless, they are helping to prepare the region to cope with, and try to avoid, the worst impacts of global warming.

THE CENTER FOR GIRL’S EDUCATION was founded in 2007 by US medical anthropologist Daniel Perlman. Northern Nigeria has some of the highest rates of maternal mortality in the world, and Perlman had been conducting research in and around Zaria on ways to prevent women from dying during childbirth. Maternal mortality is a multifaceted problem, but early marriage has been shown to be a significant factor—globally, complications from pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of death for 15-to-19-year-old women. In the communities where Perlman was doing his research, the average age of marriage for females was about 15, and sometimes girls would marry as young as 12.

Perlman found that while most families considered keeping girls in school a viable alternative to marriage, few were willing or able to enroll their daughters past primary school. Nigeria’s government-run schools are free except for registration fees and the cost of uniforms and supplies; for the poorest families, however, these expenses are prohibitive. The quality of education is also notoriously poor. One mother told Perlman that even though her daughter had graduated from secondary school, she didn’t know how to read or write, and the mother had decided not to send her younger daughters. According to Perlman’s research at the time, a quarter of the girls in the communities surrounding Zaria dropped out during the final years of primary school, compared with just 5 percent of boys. Of the girls who graduated from primary school, only a quarter went on to secondary school.

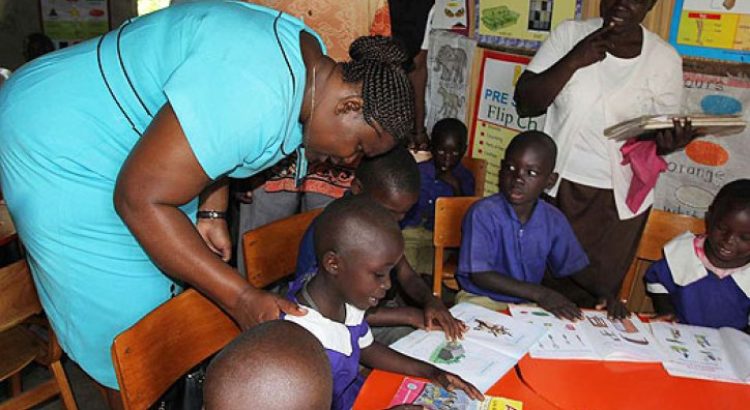

A TEEN PRACTICES HER NUMBERS.

CGE set up its first program in the village of Dakace, a dusty collection of buildings inhabited by subsistence farmers and day laborers near Zaria. There, the center organized a handful of what it calls «safe spaces»—girls-only after-school clubs where 12-to-14-year-olds work with a mentor on reading, writing, math, and practical life skills. The hope was that with the extra support, girls would improve their academic performance at school, and families would be motivated to keep them enrolled, thus delaying marriage.

At first, the safe spaces were a hard sell. Mardhiyyah Abbas Mashi, an Islamic scholar and the chair of CGE’s board, led the center’s community-engagement efforts in Dakace. She met with thesarki—the village chief—and the local imam to enlist their support. A tall, elegant woman, Abbas speaks with calm authority. «As a teacher in Arabic and Islamic studies, and as a Hausa [the dominant ethnic group in northern Nigeria], I know the culture. I know the religion. So that is why we go to the community and we talk about the importance of girls’ education in Islam,» she says. «The very first commandment that came to the Prophet was to read. In Islam, knowledge is compulsory for you whether you are a man or a woman.»

The sarki and the imam agreed to the plan, but others in the community remained suspicious. Rumors flew: The real purpose of the safe spaces was probably to teach family planning, the point of which, everyone knew, was to get Muslim women to have fewer babies in order to reduce the Muslim population.

The sarki, Saidu Muazu, called a community meeting to address people’s fears. «I made them understand that there are a lot of boys continuing with their education, but girls are not continuing,» Muazu says, «and that when a girl has an education, she will make a better person in her home, in the community, and everywhere she finds herself.» Eventually, a small group of parents agreed to enroll their daughters in the safe spaces.

AMINA YUSUF

Amina Yusuf was one of those girls. Despite having just finished primary school, she could barely recite the alphabet, let alone read a book. At the government-run primary school she had attended, she had been in classes with as many as 300 students. It was chaos. To maintain order, instructors would beat the students with sticks.

By the time Yusuf began attending a safe space at age 12, many of her friends were married. «I thought it was just a normal way of life,» she says. But her mother had received some education as a girl, and her father thought she should as well.

The safe space was held three afternoons a week. Unlike Yusuf’s teacher at school, the mentor knew her by name; if Yusuf didn’t understand a lesson, the mentor followed up with her individually. Plus, the snacks were good.

Yusuf would come home from the safe space and teach her seven siblings what she had learned and also share tips with her mother, like how to keep a clean kitchen so no one got sick. Her parents were impressed. In the past, her father had not paid much attention to her, but now he pointed her out to others, saying, «That’s my daughter.»

Mohammed was a mentor at one of the first safe spaces in Dakace. At the time, she was a teacher at a secondary school. Sometimes she had up to 90 students in a class, and she was also raising eight children. But in her first weeks as a mentor, she was taken aback by how difficult it was to work with the 15 12-year-olds in her safe space. They were unruly, and fights broke out, often for trivial reasons such as someone’s hand accidentally brushing someone else’s. «Whenever I came back home after my safe space, I had terrible headaches,» Mohammed recalls. «I’d think, ‘Should I continue this work? Am I really meant for it?'»

Mohammed had grown up in a family of three girls and one boy. Her mother had always encouraged her and her sisters to do their best. «In Nigeria, if you have a girl child, people tend to look down on you, thinking that you have not gotten a boy child that will carry the name of the family, but my mother always made us understand that a girl can do what a boy can do,» Mohammed says. «Even when I was married and I was going to school, my mother was always there to support me, helping me in whatever way she could.»

Thinking about this made Mohammed feel a deep responsibility to the girls in her care, despite the challenges of the work. She and the other mentors began meeting regularly to swap stories and advice, in essence forming a safe space for one another. Gradually, the girls’ behavior began to improve.

Over time, the center’s mentors, who are all volunteers, have gotten better at helping adolescent girls with little to no real education. They’ve incorporated movement, storytelling, and singing into their lessons to teach basic literacy and numeracy skills. It has been a quietly radical experiment, this refusal to give up on girls from the poorest families.

Maryam Albashir joined the program as a mentor in 2010 and is now a team leader for CGE’s Transitions Out of School project. «One good thing about working with this center is you learn to accommodate everybody, whether or not you are of the same status, wherever you are from,» she says. «We don’t really have that in our schools in this country. You get spanked; you get punished. However the teachers want to treat you, they treat you. We were supposed to enroll about 30 girls in a school, but the principal rejected them, and her reason was that she didn’t see people of their caliber coming into school. She didn’t give them a chance; she just defined them.»

In Dakace, Muazu says, there has been a big shift in attitudes toward girls’ education. «People within the community started seeing the impact in the girls, so they got impressed. Right now, the number of girls who are in school is more than the number of boys because of the help from the center.»

Girls who have graduated from the safe spaces frequently stay on and become what the center calls «cascading mentors.» Now 22, Yusuf works on a CGE project called the Girls Campaign for Quality Education, which teaches girls how to advocate politically for better access to education. She is enrolled in college and is studying science education. She is not married. «I want to make sure that I marry a man who will allow me to continue my education,» she says.

Perlman believes that the Center for Girls’ Education is succeeding in its original goal of decreasing maternal mortality: According to his research, the age of marriage for girls who participate has been delayed by an average of 2.5 years. But even if this were not the case, he would deem the program a success because of the way it has transformed the lives of girls like Yusuf. His data shows that 80 percent of the girls who went through the program in its first few years went on to graduate from secondary school. Now 70, Perlman still travels to Zaria frequently to collaborate with Mohammed and other staff members on program design and implementation. «Even old white men can be allies,» he likes to say, «as long as they understand that the people who have the problem have the solution.»

NIGERIA IS THE SEVENTH-MOST-POPULOUS nation in the world, with just over 200 million people living in an area roughly twice the size of California. And it’s growing fast—Nigerian women have, on average, five children. By 2050, the country is projected to have the third-largest population, with more than 400 million people, the vast majority of whom will be under the age of 24. Tens of millions of young people will need education and employment opportunities along with basic services like sanitation and clean water. Without these, they will be mired in poverty and vulnerable to extremism in a country that already contends with Boko Haram and other terrorist groups.

Add to this list of challenges the impacts of climate change. Nigeria’s northern border is perched on the edge of the Sahel, the semiarid belt that stretches across the southern rim of the Sahara Desert. By 2050, average temperatures in the Sahel could rise by as much as 2°C. Hotter temperatures will mean drier soil that retains less moisture, and this will make it harder to grow food, especially for subsistence farmers.

Yusuf Sani Ahmed, an agricultural expert at Ahmadu Bello University, says he already sees the signs of climate change in Zaria. «The temperature can be 44 Celsius, which is high, and the streams are becoming drier and drier.» Because the water table is low, he says, there’s less vegetation, and livestock have become thin and malnourished.

Ahmed is on good terms with the herders whose cattle graze near his fields, but he says that shrinking arable land coupled with too much development is exacerbating conflicts between farmers and herders throughout the north; violent clashes are on the rise. «There’s less available land, and also not much is growing because things are drier,» he says. «It is so competitive.»

Girls’ education plays an indirect but crucial role in helping to alleviate these complex problems. The book Drawdown—a compendium of strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions—places girls’ education at number six on its list of the 100 most effective solutions to climate change. Aside from helping communities become more resilient, girls’ education has a significant effect on population growth. «Women with more years of education have fewer, healthier children and actively manage their reproductive health,» the Drawdown researchers say, noting that, on average, a woman with 12 years of schooling has four to five fewer children than a woman with no education.

In a report for the Brookings Institution, Christina Kwauk and Amanda Braga call girls’ education «one of the most overlooked yet formidable mechanisms for mitigating against weather-related catastrophes and adapting to the long-term effects of climate change.» But they also warn that fixating too much on population growth in low-income countries can be fraught with ethical problems. «For one,» they write, «it places the cost for reproductive decisions on girls and women in the Global South while ignoring other anthropogenic factors that contribute to climate.» For example, the average American produces 16 tons of greenhouse gas emissions annually, while the average Nigerian emits only .55 tons.

Ultimately, improving girls’ access to education around the world helps address the strain that an increasing number of people places on fragile resources—for example, arable land and fresh water—in a way that advances basic human rights for women and girls. «If universal education for girls were achieved tomorrow,» Kwauk and Braga write, «the population in 2050 could be smaller by 1.5 billion people.»

When I feel labor pains begin, I go to the hospital!

When I feel labor pains begin, I go to the hospital!

HABIBA MOHAMMED STANDS before a group of about 20 girls in a dim room with mud-brick walls in the village of Marwa, not far from Dakace. She is a guest at today’s gathering, and she leads the girls in a call-and-response about going into labor and giving birth. While she sings, she trembles, grabs her back as if in pain, and doubles over. The girls imitate her gestures, their pink, red, blue, and green hijabs billowing.

This safe space began less than a year ago. The mentor, Khadijah Mohammed (no relation to Habiba), says that when they started, none of the girls could write their names. «Now they can write their names, the name of their community, their parents’ names, and so many other things,» she says. Most of these girls have never been enrolled in school; now they are preparing to take a placement exam to enter primary school. «They have ambitions now,» Khadijah says. «Some of them want to become doctors, some teachers. They have hope for their future.»

Today’s lesson is mostly a review of reproductive health—hence, Habiba’s call-and-response. «How do you know when you are pregnant?» Khadijah asks. «Once you are pregnant, when should you go to the clinic?» The girls talk over one another to answer.

CGE’s safe space curriculum includes a field trip to a medical clinic. For many students, it’s the first time they’ve been to one. Sometimes this is because the nearest clinic is far from where they live. Their families’ low social status can also interfere. «When they go to the hospital, they don’t feel very confident with the workers, so they don’t get what they want,» Khadijah says. On the field trip, the girls talk to nurses, doctors, and women who have just given birth. «Some of [the students] are very shy to the doctor during that visit,» Khadijah says, «but some of them are confident. They ask questions.»

Operating in a religiously conservative area, CGE does not explicitly teach family planning. Nonetheless, the girls who take part in the safe spaces are more likely to use birth control than those who don’t, partly because of the greater exposure to information they receive in school.

In their study, Kwauk and Braga also argue that higher levels of education are associated with strong measures of agency—or, «the ability to make decisions about one’s life and act on them to achieve a desired outcome, free of violence, retribution, or fear.» For this reason, girls’ education complements family-planning services, which on their own aren’t always effective.

Despite the efforts of CGE and other organizations working to advance girls’ education, fewer than one in three girls in sub-Saharan Africa attends secondary school. Advocates say that if some climate-adaptation funds—which are often focused on expensive, highly technical solutions—were delivered to organizations that educate girls, this low-tech, equity-focused response to climate change could rapidly scale up.

But for Perlman, Mohammed, and others at CGE, that isn’t really the point. Their work is, above all, about fostering female agency. The center has flipped the script that usually accompanies Western-led aid and development programs in poorer nations. Female education isn’t an instrument to some other goal—it is the goal, with the broader environment representing a kind of co-benefit. And this is exactly why it works.

«Something has really taken place to make people better,» Mohammed says, «and it is helping more girls to be able to have the support of their parents to allow them to continue schooling and to really achieve something with their life.

Source of the notice: https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/2019-6-november-december/feature/educating-girls-may-be-nigerias-best-hope-against-climate

Users Today : 14

Users Today : 14 Total Users : 35460815

Total Users : 35460815 Views Today : 24

Views Today : 24 Total views : 3420054

Total views : 3420054