Dedicado a la memoria del Presidente Chávez, al legado de Ajishama, a la lucha de Sabino Romero, al trabajo de Hernán González, a Shejerume mujer Wotuja,Lucia, mujer Yukpa y a todos y todas los estudiantes de la Universidad Indígena de Venezuela.

Introducción

La investigación propone discutir el tema de las identidades juveniles presentes en estudiantes de diferentes pueblos indígenas de Venezuela quienes tienen como característica común el haber cursado o estar cursando estudios universitarios en la Universidad Indígena de Venezuela (UIV). Es preciso destacar que desde su creación, antes del reconocimiento por parte del Estado venezolano, esta casa de estudios fue concebida como un proyecto educativo que priorizó el ingreso de jóvenes indígenas.En consecuencia, esta concepción fue considerada en la redacción del Decreto Presidencial Nº 8.631 de de fecha 29 de noviembre de 2011, documento que la formalizó como la primera universidad indígena del país por cuanto en el objeto del mismo, la UIV se concibe como un espacio para “(…) afianzar en los pueblos y comunidades indígenas los principios y fundamentos de las culturas originarias valorando su idioma , cosmovisión ,valores, saberes y mitología (…)”.

Por otro lado, es esencial aclarar que este trabajo se ocupa de la indagación de un universo representativo de estudiantes indígena de la UIV, de manera que no abarca aquellos indígenas cursantes del resto de las universidades criollas del país[1].

Se advierte que en Venezuela el tema sobre juventudes indígenas no ha sido explorado como un campo teórico específico. En consecuencia, no existen estudios sobre las configuraciones identitarias de los indígenas que se asumen como jóvenes estudiantes. Sin embargo, la existencia del tema visto a la luz de investigaciones en realidades universitarias en países como México, Colombia y Perú, allanaron el camino para plantear este trabajo desde el punto de vista teórico y situarlo en el marco de categorías de análisis flexibles capaces de enunciar las cualidades más emergentes y rupturas a partir de la deconstrucción del concepto joven e indígena y su relación con la experiencia de ser estudiante universitario.

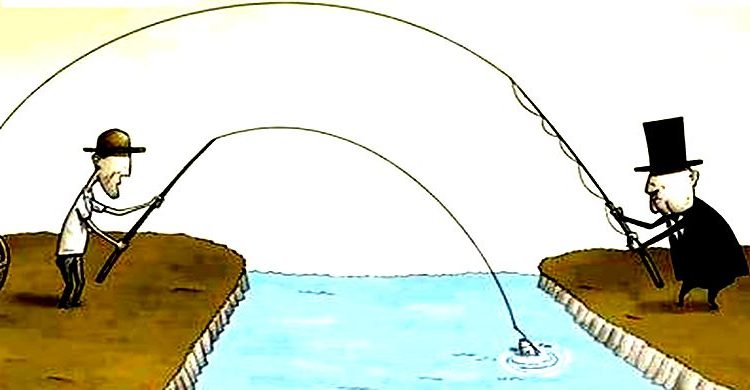

Los testimonios de los entrevistados son para esta investigación fuente de conocimiento que permiten vislumbrar un camino más comprensivo sobre los las juventudes indígenas. Al mismo tiempo, las voces de estos estudiantes indígenas aportan en el debate sobre la pertinencia de la educación universitaria[2] no solo como un medio para la formación de profesionales o mano de obra técnica, sino como proyecto de liberación de los pueblos indígenas. Para cumplir con lo planteado, este trabajo indaga sobre aspectos de la socialización presentes en los estudiantes indígenas, el papel que desempeña la universidad en sus vidas, las descripciones que ellos y ellas hacen sobre quien es joven indígena y el futuro que proyectan como juventudes a partir de sus experiencias en la Universidad Indígena de Venezuela.

La parte inicial de la exposición discurre sobre el complejo tejido argumentativo necesario para abordar un lugar teórico práctico que permita convencer sobre la existencia de jóvenes indígenas a partir de las múltiples “variaciones en la definición y caracterización de lo joven, según los actores y sus contextos de enunciación (autocaracterización vs. heterocaracterización), organizados por posición cultural, social y de género” (Pérez Ruiz,2011:73). De igual manera, la investigación explora en lo que considera una categoría emergente que es la de jóvenes estudiantes indígenas, condición que equilibra en la UIV las relaciones entre sujetos que pertenecen a pueblos originarios diferentes los unos de los otros.

Por otra parte, este trabajo caracteriza a la Universidad como espacio de socialización cultural que influye en la configuración de identidades juveniles indígenas. La UIV permite a los estudiantes identificarse con un proyecto político educativo que les otorga la libertad de ser ellos, de ser ellas, a partir de ciertos mecanismos que les permiten negociar algunas de las pautas culturales propias de cada uno de los pueblos a los que pertenecen, sin obviar el hecho de que este proceso de negociación-flexibilización son constitutivos a la existencia de fuerzas que están en tensión permanente con los referentes de la juventud criolla.

El enfoque metodológico se ubica dentro del ámbito cualitativo enmarcado en la investigación acción. Con este enfoque se avanzó en conocer la realidad del objeto de estudio en movimiento con sus relaciones y sus contradicciones. Las voces de los estudiantes pertenecientes a los pueblos Wotuja, Pumé, Pemon, Yekuana, Eñepá, Yukpa, Jivi, Wayu y Warao son las protagonistas en esta investigación.El análisis estuvo centrado en la perspectiva de los actores mediante la escucha de su palabra, lo cual, fue sin duda, fuente inexpugnable de conocimiento. Las vivencias de estos, sus visiones del entorno, el recuerdo de sus trayectorias de vida cuyos datos biográficos aluden a instancias socio históricas y culturales, me permitieron irrumpir en el debate sobre las “juventudes indígenas” a partir de la perspectiva construida por los estudiantes. La decisión metodológica estuvo definida por la necesidad de vincular las voces de los entrevistados a ciertos aspectos teóricos referidos al tema juventudes, indígenas y educación universitaria. En analogía con el texto de Ana Lau Jaiven (1998), “Cuando hablan las mujeres”, esta investigación se propuso visibilizar realidades objetivas y subjetivas de estos estudiantes, por tanto se revelan datos importares a partir de cuando hablan los jóvenes estudiantes indígenas.

En cuanto a los instrumentos para la recolección de la información se empleó las entrevistas en profundidad dirigidas a 21 estudiantes indígenas, universo que se consideró representativo por pertenecer todos al total de los pueblos que para el periodo del estudio se encontraban presentes en la UIV: Pemon, Wotuja, Warao, Yekuana, Yukpa, Pumé,Eñapá. De igual modo, se incorporaron dos entrevistas de estudiante Wayu y Pemón quienes cursan estudios en universidades criollas, esto con la intención de consolidar el objetivo relacionado al papel que juega la educación universitaria hegemónica y la intercultural. Las entrevistas fueron semiestructuradas, centradas en conversaciones intencionales con los estudiantes y que fueron de utilidad para organizar a partir de relatos testimoniales, aquellas vivencias personales o sucesos significativos desde el punto de vista histórico de su realidad social. En algunos casos la narración se centró en la propia vida del informante, lo cual acerca algunas entrevistas a relatos de vida. Por otra parte, se procedió en el diseño de un cuestionario aplicado al total de la población de 72 estudiantes que se encontraban cursando estudios en el segundo periodo académico del año 2013. La intención de este fue el de visibilizar tendencias en cuanto a espacios para la socialización, representaciones sociales, gustos musicales, motivaciones sobre el estudio y perspectivas a futuro. El cuestionario planteado fue de tipo combinado, es decir, en el que se encontraron presente preguntas abiertas no estructuradas, pregunta cerrada dicotómica y preguntas de tipo mixta, en las cuales se propuso la explicación o justificación de su respuesta. Se acordó fecha y hora para que todos los estudiantes reunidos en la churuata ateneo[3] respondieran las preguntas. La selección de los casos y trabajo de campo, esta fue intencional a partir de:

- Estudiantes indígenas que antes de empezar su ciclo en la UIV, cursaron estudios en instituciones

- Estudiantes que para ir a la UIV, fueron postulados por la comunidad y que no transitaron por ninguna institución criolla.

- Estudiantes que por mandato comunitarios tuvieron que interrumpir sus estudios en la UIV.

- Estudiantes mujeres que por situaciones relacionadas al “ser mujer” tuvieron que interrumpir sus estudios en la UIV.

- Estudiante que cursa trayectoria final o último semestre en la UIV.

- Estudiantes que son líderes en su comunidad de origen.

- Estudiantes cursantes en universidades criollas.

En cuanto a los controles para el trabajo de campo, antes de proceder con todas las entrevistas, se realizó una prueba del instrumento en dos casos lo que permitió rectificar algunas de las preguntas. Todas las entrevistas fueron efectuadas por la autora de esta investigación, están grabadas y se realizaron en espacios de la Universidad escogidos por los mismos estudiantes a partir de la consideración de la privacidad de la persona entrevistada. Algunos de estos espacios fueron a lo interior de la churuata Eñapá sentados una hamaca, sobre el banquito improvisado debajo de un gran árbol de mango, sentados por la noche en medio de la residencia estudiantil de la comunidad Yekuana. Adicionalmente, las observaciones del trabajo de campo referentes a la actitud del informante, las clases de los demás profesores o facilitadores, los espacios de juego y tiempo libre fueron recogidas en libreta de apuntes y en algunos casos grabadas. La confidencialidad de las entrevistas está garantizada. Cada estudiante tiene su nombre escogido a partir de su lengua que es el nombre con el cual se conocen entre ellos en la UIV y el nombre criollo que es el que aparece en el documento de identidad. Lo que se hizo fue escoger un seudónimo.

Durante el proceso de recolección de la información el acercamiento con los estudiantes no fue difícil por cuanto he estado familiarizada a partir de mi participación como facilitadora durante los últimos cinco años en la UIV[4]. Con respecto al procesamiento y análisis de la información, el registro de cada entrevista se hizo mediante la grabación del audio previa autorización del entrevistado y luego fueron transcritas textualmente. Se diseñó un esquema para el análisis a parir de los objetivos específicos. En cuanto a la validación y confiabilidad de los resultados se tomó en cuenta los criterios de credibilidad, transferibilidad, dependencia y confirmabilidad (Guba, E.G; Lincoln, Y.S,1985: 85) y las técnicas y controles metodológicos de Thomas Skirtc (Ruiz e Izpizua,1989:76) los cuales estuvieron sujetos a la observación persistente de la realidad, así como a la permanente retroalimentación de los datos. Se triangularon todos los datos con las técnicas de recolección de información, análisis de investigaciones previas sobre el tema de juventudes indígenas y con las notas de campo[5] recabadas durante todas las visitas a la UIV .Importante resaltar el hecho de que se compartió con los estudiantes indígenas los resultados de la investigación durante dos encuentros pautados para este fin. Esto permitió corroborar hallazgos de la investigación, sobre todo los relacionados a quién es un joven indígena para estos estudiantes y cuál es su papel como juventudes a partir de las reflexiones continuas que realizan en la Universidad Indígena.

Juventudes indígenas y la categoría de estudiantes

Apela este trabajo por la categoría joven estudiante indígena[6] entendiendo que se trata de distintas identidades y distintas formas de asumirse joven. Es vital reconocer que el tema ha estado mediado por una afirmación que se ha hecho casi absoluta o tratada como una verdad y es lo referido a que entre los pueblos indígenas el niño pasa a ser adulto. La estrategia para ubicar un focus teórico sobre juventudes indígenas la señaló el hecho de que existe “una necesidad de reconceptualizar la infancia y la juventud desde una perspectiva latinoamericana (como ámbito geográfico, académico y cultural), abordando las nuevas formas de ver y vivir estas edades que se configuran con el cambio del milenio” (Feixa, 2002 en Feixa y Cangas, 2006: 172). Por ello, es necesario entender que nos encontramos ante un reto o “una emergencia de algo que puede denominarse período juvenil en los pueblos como en las ciudades” (Castro Pozo, 2008: 7) lo que conduce a establecer como categoría lo juvenil étnico, a lo que se le suma el mandato de visibilizar al sujeto joven en un amplio marco de identidades.

El tema de las clasificaciones sociales impacta en la perspectiva y en la intencionalidad con la que se quiere abordar las investigaciones sobre juventudes indígenas. De allí que antes de nada se deba explorar la clasificación sobre lo que es ser “indígena” tomando en consideración la construcción colonial que sobre ese término se ha ido afianzando.“Aunque la identidad indígena ha sido apropiada y resignificada políticamente como una identidad transétnica y transcultural para aglutinar la gran diversidad de poblaciones con orígenes prehispánicos que luchan para obtener sus derechos como pueblos, para estos actores es claro que su identidad como indígenas (heterodenominación impuesta en la Colonia y apropiada en la actualidad) no sustituye ni es equivalente a la identidad que consideran como la propia (autodenominación) y que han construido históricamente desde ciertos criterios para marcar su pertenencia a un lugar, a una cultura y a una lengua, y que hacen evidente y ponen en acción en ciertos contextos de interacción para diferenciarse de otros a quienes consideran ajenos” ( Pérez Ruiz,2011:67).El uso de “indígena” o” indio” remite a una nominación que “en contextos de asimetría y dominación constituye un aspecto revelador de las relaciones interétnicas, en tanto que evidencia uno de los mecanismos de la etnización, al tiempo que es en sí mismo un hecho productor de etnicidad” (Idem:68). A partir de las apreciaciones anteriores, este trabajo rechaza de cualquier intento de caracterización esencialista a partir de las identidades de los estudiantes de los pueblos Wotuja,Yekuana,Pemon,Pume,Yukpa,Warao, Jivi, Eñepá y Wayu. Intenta si, visibilizar a estos actores sociales en relación con sus contextos socio históricos, para cooperar con narrativas que abracen la construcción teórica y cultural de la juventud a partir de la diversidad (Feixa y Cangas: 2006:177).

Ahora bien, es necesario establecer puentes para entender a estos jóvenes quienes en el marco de la educación como un derecho universal, aspiran a su ingreso a educación universitaria. Diversos estudios sobre estudiantes indígenas han sido desarrollados en México, Perú y Bolivia. Los mismos se centran en caracterizar las barreras y obstáculos que los estudiantes indígenas experimentan en el marco del acceso a la educación universitaria y algunos en el análisis de los programas de apoyo dirigidos a estos.(Castillo Martínez, L., Aguilar-Morales, J.E. y Vargas-Mendoza; Raesfeld,L; Escobar J, Largo E,Peréz Carlos; Villasante Llerena,M). La revisión de estos trabajos permitieron identificar elementos que son afines a las realidades de los estudiantes indígenas que protagonizan esta investigación asociados su ingreso y permanencia en la educación universitaria.Por ejemplo, en un caso de estudio dirigido a estudiantes indígenas Zapoteca y Mixe de la Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca, las conclusiones derivaron a los problemas que estos indígenas identifican como barreras para su ingreso y permanencia en la universidad. Estos se refieren a las dificultades económicas, la incertidumbre ante su inserción laboral en el mercado de trabajo del estado, la preocupación por pasar las materias, problemas de salud que enfrentan alguno de sus familiares y la precepción de “tener miedo” a no terminar su carrera (Castillo Martínez et al. ,2009:35). En correspondencia con otro estudio de caso sobre estudiantes indígenas de la Universidad Autónoma de Hidalgo, se señala el hecho asociado a que la mayoría de los estudiantes encuestados expresaron que son discriminados por el hecho de ser indígenas (Raesfeld y Ramírez, 2008). En Colombia, la investigación realizada durante el periodo 1994-2006 sobre factores asociados a la deserción y permanencia de estudiantes en Universidad del Valle concluye “que aquellos estudiantes que poseían fenotipos indígenas eran quienes tenían más probabilidad de desertar en un 49%, comparados con los estudiantes con fenotipos negros también identificados en el estudio” (Escobar et.al,2006:72). En Bolivia, el estudio referido a educación superior y pueblos indígenas de IESALC – UNESCO (Vargas, 2004) advierte sobre la invisibilización de los estudiantes indígenas lo que acarrea un desconocimiento generalizado de sus realidades étnicas y en consecuencia “las políticas de educación superior no consideran orientaciones específicas para las poblaciones indígenas como tampoco dispositivos que favorezcan la ampliación, acceso y cobertura de la educación superior” (Vargas: 66). Esta realidad se evidencia también en el estudio llevado a cabo en la Universidad del Cusco en Perú en el cual se evidencia que en dicha casa de estudios “no existen estadísticas reales acerca de la demografía, identidades, idiomas, lenguas y otras características de los alumnos y por sobre todo sobre los tipos de atención educativa que reciben los estudiantes indígenas”(Villante,2002).

En el caso de Venezuela los estudios relevantes sobre los jóvenes indígenas universitarios no han sido objeto de preocupación por las ciencias sociales, mas no así los estudios referidos a la juventud en general. Este tema ha tenido un avance progresivo desde el punto de vista de abordaje teórico y metodológico. Investigadores del área reflexionaron de la perspectiva positivista que había estado dominando en las investigaciones desarrolladas desde 1.878 hasta la década de los 50. A finales de los 80 con la conformación de equipos de investigadores en la Universidad Simón Bolívar y Universidad Central de Venezuela se inició como “un esfuerzo de reflexión acerca el concepto de juventud, cuestionando los enfoques que lo definen como un dato acotado estadística y demográficamente y llamando la atención sobre la necesidad de definir el concepto de juventud a partir de los jóvenes desde su ámbito social de vida y no con los criterios del mundo adulto” (Bermúdez et al.,2010: 93). Así mismo, se incorporan a los estudios variables de la cultura política sobre todo porque los 80 y 90 en Venezuela estuvieron marcados por profundas crisis económicas impuestas por los pactos neoliberales de los gobiernos representativos con políticas monetarias como las del Fondo Monetario Internacional. Los “jóvenes universitarios” pasan a ser el centro de atención de muchos estudiosos quienes abordaron sus trabajos desde el punto de vista cualitativo y cuantitativo. En seguida surge la representación de “movimiento estudiantil”, producto del “papel beligerante que como grupo social tuvo ese movimiento entre 1958 y 1989 (López, 2007:94) tanto en el cuestionamiento del régimen democrático como ocurrió con los movimientos de las décadas de los 60 y 70 o como protesta frente a la política universitaria, en especial la política de restricción de cupos, como sucedió en los ochenta” (Ídem).

Las reflexiones sobre las participaciones de los jóvenes en los problemas del país, asignan al concepto de “generación” un lugar privilegiado desde donde “mirar” a los estudiantes universitarios. “Esta idea de generación ha sido apropiada por el análisis y una parte del discurso político nacional actual para construir el modelo de joven que le país necesita” (Ibídem: 95).

Este breve recorrido nos lleva a la década del 2.000 y la ruptura política que se inauguró con el periodo de la Revolución Bolivariana que incorporó un amplio marco legal dedicado a los jóvenes del país. En la Constitución venezolana se consagra un artículo sobre la posición estratégica de la juventud que expresa el hecho de que “los jóvenes y las jóvenes tienen el derecho y el deber de ser sujetos activos del proceso de desarrollo. El Estado, con la participación solidaria de las familias y la sociedad, creará oportunidades para estimular su tránsito productivo hacia la vida adulta y en particular la capacitación y el acceso al primer empleo, de conformidad con la ley” (CRBV, 1999). Para el año 2002, se decreta la Ley Nacional de la Juventud donde destaca la misión de promover el primer empleo como derecho en el transito a la vida adulta. Ya para el 2.008 se exhorta una modificación de la misma que contemple un sistema más amplio de protección para la juventud estipulado en la Ley del Poder Popular para la Juventud.

Resulta oportuno citar esta ley porque define el ser joven. “A los efectos de esta Ley, sin menoscabo de otras definiciones, y sin sustituir los límites de edad establecidos en otras leyes, se consideran jóvenes a las personas naturales, correspondientes al ciclo evolutivo de vida entra las edades de quince y treinta años, que por sus características propias se considera la etapa transitoria de la adultez” (Título I ,disposiciones fundamentales, definición de joven).En el titulo referido a los deberes y derechos de la juventud, se hace referencia a las garantías de la juventud indígena y su “derecho a un proceso educativo intercultural y bilingüe, que responda a los usos, costumbres y normas originarias, así como a la promoción e integración laboral y productiva; y al goce de sus derechos ciudadanos, sin discriminación alguna”.

Observando lo anterior queda claro que la categoría juventud indígena es enunciada en el marco de lo indígena como una condición general, objeto de derechos. Mientras la categoría hegemónica de juventud ha sido estudiada en sus múltiples variables, la caracterización de ser joven y además indígena ha quedado incomunicada. Es importante indagar las razones de esta omisión que se explica como parte del dominio teórico de la caracterización de la juventud desde referentes occidentales y también al hecho de obviar las equivalencias a la fase de ciclo vital que los pueblos indígenas poseen y su reconocimiento frente al saber occidental.

Si la tendencia ha sido posicionar el tema de la juventud como grandes portadores de valores y bastiones de lucha frente a los procesos de cambio sociales y políticos de Venezuela, resulta comprensible que desde este enfoque sea invisibles las acciones de los jóvenes indígenas, quienes no han sido sujetos protagónicos de revueltas populares nacionales o manifestaciones universitarias, esto solo por nombrar algunos eventos que han servido para llamar la atención de estudiosos del tema. La construcción hegemónica de “esa imagen de generación sobre el papel de la juventud en los procesos políticos” ha sido la única tomada en cuenta, “el problema es que a partir de esa construcción elaborada por políticos e intelectuales se ha creado una representación sobre el papel que como actor político debe jugar la juventud en Venezuela y acerca sus prácticas, de tal forma que ello impide mirar otras iniciativas que tienen que ver con diferentes maneras de hace política por parte de algunos grupos de jóvenes actualmente”(Bermúdez et al., 2010:105).

El objeto de estudio de lo “joven” ha sido asociado a sujetos a partir de sus experiencias como estudiantes universitarios, sujetos contestatarios frente a políticas públicas de redistribución de recursos, sujetos para el consumo, actores políticos y datos demográficos. Pero los adolescentes y jóvenes de los diferentes pueblos indígenas, no han sido incluidos en el discurso. Ellos y ellas son claves para comprender las situaciones de deterioro progresivo de las cientos de comunidades indígenas del país, así como claves en manifestar sus esperanzas frente un futuro que parece incierto. Con esto no se quiere decir que en Venezuela se haya obviado los estudios etnográficos sobre la presencia indígena en general. Pero el sujeto de análisis en la mayoría de los casos ha sido un hombre adulto visto como chaman o guardián de la cultura amenazada; sujeto en profundo proceso de pérdida de identidad, sujeto pobre materialmente o victima de la violencia ante la pérdida progresiva de los territorios frente a los terratenientes.

La población indígena de Venezuela se encuentra presente en casi todo el territorio nacional, tanto en centros urbanos como rurales, los cuales no son necesariamente asentamientos tradicionales. Datos revelan que el 63,24% de la población que se autoreconoció como indígena reside en zonas urbanas, lo que conduce a valorar a los fenómenos migratorios como realidades de gran incidencia en este mapa nacional. El censo 2011 registró un total de 52 pueblos indígenas que constituyen el 2,7 % del total de la población venezolana; en cifras esto corresponde a 724.592 personas auto reconocidas como indígenas de 26.503.338 no indígenas. (Instituto Nacional de Estadística 2011, Resultados básicos del censo indígena en XIV censo de población y vivienda). El censo reconoce así que aunque hubo un crecimiento del número de venezolanos auto reconocidos como indígenas, hubo una disminución en quienes son hablantes de sus idiomas de origen. El censo también revela una disminución relativa de los menores de 15 años y un incremento de la población en edad potencial de trabajar de 15 a 64 años; también “se observa una disminución relevante de la dependencia juvenil, menores 15 años, como evidencia de la disminución de la fecundidad. Incidiendo en el desplazamiento de la edad mediana de 19 años (censo 2001) a 21 años según el censo 2011”. (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2014. Resultados Censo indígena 2011). En cuanto a las características educativas, el censo no precisa cuantos indígenas están en universidades, solo destaca un aumento en las cifras de alfabetización y un estimado de la brecha frente a los no indígena de alrededor de un 30% (Ídem).

Para investigar a los “jóvenes indígenas” es necesario saber que se trata de un campo sin conclusión absoluta y buscar superar “la mezcla arbitraria entre la temática delo joven en general, de lo “étnico e indígena en general”, o sólo de la derivación hacia lo joven desde otras temáticas relevantes, como la migración, la educación, la salud” (Idem: 73). Existe una inclusión problemática de las distintas realidades de los jóvenes indígenas frente a una realidad nacional que presiona de forma agresiva los sistemas sociales indígena, cada día más fragmentada. Se han alterado los sistemas que tradicionalmente han incido en las pautas de socialización de la infancia indígena lo que conlleva a profundas modificaciones en las distintas construcciones de la identidad. Las realidades de exclusión material y las ausencias subjetivas en los campos del saber, otorgan al problema un carácter de urgencia, y que se visibiliza en los jóvenes estudiantes de la Universidad Indígena de Venezuela. Desde el punto de vista de estudios decoloniales, cuando me refiero a las identidades, entiendo estas como “procesos amplios de formaciones de sujetos, que expresan no sólo personalidades particulares , sino también agrupaciones colectivas [así] las identidades comprenden un medio crucial a través del cual los procesos sociales se perciben, se experimentan y se expresan” ( Saurabh,2009). Por consiguiente, las identidades juveniles protagonistas de esta investigación están definidas por relaciones históricas de producción, poder y aprobación. Se intenta subvertir la institucionalización de lo que es ser joven, indígena y estudiante universitario, para se conjugan elementos críticos sobre la construcción de la raza, las divisiones de género y clase, para avanzar en rectificar en la medida de este humilde aporte, el desequilibrio que reina en las construcciones hegemónicas de las categorías de análisis enunciadas.

Desde esta posición de sujetos subalternos se propone el análisis del tema. La producción de la juventud indígena situada en los diferentes pueblos es observada y problematizada desde las realidades de migración,caso de jóvenes del pueblo Jivi; educación secundaria, tema central en todas las experiencias; consumo hegemónico de redes sociales,muy presente entre jóvenes yekuana y pemon,el devenir de la Universidad Indígena de Venezuela como espacio que enfatiza lo juvenil desde el elemento común dado por el hecho de ser estudiante y por último el tema de género y relaciones de poder. Falta aproximarse a especificidades que dan lugar a estos procesos amplios de “resemantización”, y que sin duda cumplen con objetivos vitales en las trayectorias de vida de estos estudiantes. Las configuraciones identitarias de estos indígenas buscan un lugar con sentido protagónico en la sociedad venezolana, específicamente instando a la reflexión de la educación universitaria.

Breve caracterización de la Universidad Indígena de Venezuela

La Universidad se inspira en particular con la creación de la Universidad Intercultural de las Nacionalidades y Pueblos Indígenas “Amawtay Wasi” en Ecuador, y en general con en el movimiento de instituciones indígenas del continente. El camino de la UIV por el reconocimiento por parte del Estado venezolano ha estado marcado por momentos de tensión producto de las necesidades económicas para garantizar la atención de los estudiantes en materia de alimentación, transporte, salud así como también infraestructura. Esta realidad llevó a la Universidad a solicitar apoyo en distintos entes gubernamentales, aun y cuando, al interior de la misma no se había planteado como objetivo fundamental contar con el reconocimiento oficial. Al respecto, uno de los fundadores afirma que “para nosotros los mas importante fue y ha sido el reconocimiento de los pueblos indígenas, sin embargo, la realidad económica fue la que nos llevó a encaminarnos por el reconocimiento oficial para contar con un presupuesto que garantizara su funcionamiento y permanencia en el tiempo. Una de las primeras puertas que tocamos en el 2007 fue la de Fundayacucho[7], institución que empezó a prestarnos un apoyo económico muy modesto dentro del programa de becas del poder popular” (González,2013). Importante es destacar que en un acto de entrega de becas en la que asistió el presidente Chávez, una representación de cuatro estudiantes de la UIV indígenas fue invitada. Al final del discurso del Presidente, Wesiyuma, para entonces coordinador académico, pidió derecho de palabra para solicitarle al Presidente Chávez el reconocimiento de la UIV. En respuesta, el mandatario nacional accede a dicha petición, acción que marcó en la vida de la UIV un antes y un después. Transcurridos unos días, el Ministerio de Educación Universitaria contacta al equipo académico de la UIV para acordar pautas del trabajo conjunto en dirección a su declaración formal. Finalmente, la UIV fue reconocida en el marco de la Misión Alma Mater[8], misión que se creó con el propósito de impulsar la transformación de la educación universitaria venezolana bajo criterios de articulación institucional y territorial, estos en función de las líneas estratégicas del Proyecto Nacional Simón Bolívar[9], garantizando el derecho de todas y todos a una educación superior de calidad sin exclusiones.

Se resalta el hecho de que el nombre Universidad Indígena de Venezuela fue cambiado en el decreto 8.631 y en Gaceta Oficial No.39.810 por el de Universidad Nacional Experimental Indígena del Tauca (UNEIT), aspecto que fue debatido al interior de la UIV por considerar que representativamente el alcance reconocido oficialmente se circunscribiría solamente a los indígenas del estado Bolívar y Amazonas y no como lo que es en realidad, una universidad para todo los pueblos indígenas el país.

Si bien el reconocimiento aconteció en el año 2011, la creación de la UIV data del año 2000 cuando fue registrada como la asociación civil Universidad Indígena de Venezuela. El hermano Jesuíta José María Korta Ajishama, conoce el Caño Tauca del Municipio Autónomo Sucre del Estado Bolívar en el año 1992, lugar que se convierte en sede de “Causa Amerindia Kiwxi”, donde se realizó durante una década cursos de concientización y autoncientización indígena con el apoyo de un equipo de aliados a la causa y conscientes de que los propios pueblos debían ser protagonistas de su propia afirmación cultural. Para el año 2000 fue convocado un primer grupo de jóvenes indígenas de diferentes pueblos con el objeto de crear, dentro de una metodología bilingüe e intercultural, textos para ser utilizados en las escuelas indígenas, es decir, que estos jóvenes con el apoyo y herramientas de la educación criolla, realizaron sus propios libros encarnados en su cosmovisión y vida. Dicho esto, la UIV se erigió “no solo como una Universidad para Indígenas si no como una la Universidad desde los indígenas pues ellos promovieron su creación” (Korta,2012). Al inicio confluyeron en la propuesta de la Universidad solo los Ye´kuanas, Eñepá y Pumé. En la actualidad incorporan, además de las anteriores, estudiantes de los pueblos Yuckpas, Wótjüja, Warao, Jibi y los Pemon. En otro orden de ideas, la infraestructura de la UIV responde a las realidades arquitectónicas de los pueblos indígenas. Las residencias estudiantiles y las áreas comunes de reunión son en su inmensa mayoría churuatas, razón por la cual los materiales que predominan son el barro, la madera y la palma.

La Universidad está orientada a “la formación integral de los estudiantes indígenas caracterizados por su alto compromiso con las comunidades, su capacidad de organización y liderazgo, para recrear espacios culturales que ayuden a la formación de futuras generaciones” (Informe ejecutivo de la UIV presentado ante el Consejo Nacional de Universidades, 2010). La Universidad es concebida como una “universidad–comunidad, de allí que la máxima autoridad de la UIV sea el consejo de sabios y ancianos conformado por mayores de cada pueblo. En cuanto al diseño curricular, la UIV organiza el plan de estudios en un primer ciclo referido al tronco común transversalizado por los ejes de concientización, identidad y producción. El segundo ciclo se concentra en la formación especializada que culmina con un trabajo de investigación. El tiempo de la trayectoria de estudios es de 4 años. El año académico lo conforman dos semestres que se turnan uno “cursado” en la comunidad y el otro en la universidad. Educación cultural indígena, estudios jurídicos, agroecología indígena y comunicación social indígena, son las cuatro carreras que ofrece la UIV.

El proceso formativo se da en contextos concretos que son en primera instancia las comunidades “que se constituyen como espacios de investigación de exclusivo valor por la presencia de ancianos y la posibilidad de conocer mejor la cultura milenaria y las potencialidades para su rescate” (Entrevista a Hernán González, co fundador de la UIV, 2013); están también las residencias estudiantiles, donde cada pueblo tiene construida una edificación según corresponda al diseño tradicional de cada cultura. El estudiante “puede crear y recrear su propia cultura, donde habla su idioma”. Estas residencias buscan ser autogestionarias lo que se edifica como una práctica de incalculable valor pedagógico pues permite que los estudiantes reproduzcan de alguna forma ele espacio de donde son originariamente. También están las áreas demostrativas, que son “espacios de práctica y ensayo de modelos de producción, aprendizaje de nuevas técnicas y diseño de proyectos”. Por otra parte, la UIV se encuentra bajo el desafío de “validar dentro de sus programas de formación el conocimiento de los pueblos indígenas” (González,2013) como aportes a una educación universitaria concebida para y por los pueblos indígenas en su relación con sus realidades culturales y en diálogo intercultural con la sociedad venezolana.

Los estudiantes y sus contextos comunitarios

Se presenta sucinta descripción que intenta precisar los rasgos característicos de los distintos contextos geográficos, trayectorias históricas y culturales de los protagonistas de esta investigación y al mismo tiempo, nombrar los problemas que presionan la vida de las comunidades de donde provienen. No pretende ser una síntesis de datos antropológicos ni lingüistas. Procura situar al lector en las distintas realidades que impactan a los jóvenes indígenas y sus tejidos comunitarios.

La participación de los estudiantes del pueblo Yékuana en la Universidad Indígena está ligada a a su fundación y consolidación. En la década de los 70 se conformó una de las organizaciones de indígenas de mayor trayectoria en el país, la Unión de Maquiritares del Alto Ventuari, UMAV (Rivas,2014-cofundador Ecomunidad- Causa Amerindia Kiwxi, entrevista).Los Maquiritares como les llama el criollo a los Yekuana, en vez de dispersarse en su propio territorio, tal como preveían terratenientes invasores en la zona supuestos “ganaderos”, decidieron concentrarse poblacionalmente en Cacuri, organizándose también en la cría de ganado bufalino, especie adaptable al sistema climático del Amazonas y así defender su ancestral territorio. Los hijos e hijas y de esta lucha comunal Yekuana, son postulados hoy para asistir por los ancianos de su pueblo. Muchos de los yekuanas se desempeñan en roles importantes dentro de su comunidad. Hoy enfrentan graves problemas por la invasión minera en sus territorios.

Los estudiantes y las estudiantes del pueblo Pemón que asisten a la UIV son principalmente de las comunidades ubicadas en el municipio Gran Sabana. El pueblo Pemon es el tercero con mayor población en Venezuela y su cultura ha sido muy influida por la intervención de la religión occidental, a través de los misioneros católicos capuchinos y de los protestantes adventistas. Su territorio fronterizo con la Guayana y Brasil, rico en oro y diamante, ha provocado conflictos armados entre indígenas, garimpeiros y fuerzas militares, resultando, según testimonio de los propios pemones, en indígenas asesinados ya que son los que poseen mayor vulnerabilidad y menos protección de todos los actores que participan en la explotación de los minerales preciosos. Las mujeres Pemon han denunciado en distintos espacios la explotación sexual a la que son objeto algunas niñas y adolescentes en contextos donde la minería legal e ilegal ha ido desplazando las relaciones económicas comunitarias.

La mayor parte de los jóvenes Waraos que van a la Universidad Indígena de Venezuela provienen de las comunidades alrededor del caño Mariusa y Isla La Tortuga. El 40% de las comunidades waraos no tienen acceso a servicios básicos de salud debido la falta de redes de transporte fluvial. Enfermedades epidémicas como el sarampión, cólera, tuberculosis asi como el consumo de alcohol configuran uno de los riesgos a los que estas comunidades están expuestas (Wilpert;Lafée Wilpert:2008:363). El pueblo Warao ha sido una de los grupos etnicos que con mayor fuerza ha sufrido el proceso de transculturización bajo la influencia de los sacerdotes Capuchinos de la iglesia católica, la explotación del Palmito, terratenientes que han invadido parte de la tierra cultivable en el Delta (solo el 25% de la tierra es cultivable) y la empresa Petróleos de Venezuela, que ha utilizado su mano de obra barata y su experticia geográfica en el delta para la explotación del recurso La lengua Warao corre un gran peligro de desaparecer ya que se calcula que unos 18.000 mil miembros del pueblo sólo hablan la lengua originaria, unos 16.000 lo mezclan con el español y el resto de la población, solo se expresa en castellano (Luzardo,2009).

Por su parte, los estudiantes del pueblo Wotuja son de Mawako de Autana, municipios del estado Amazonas. Entre los problemas que reportan están los relacionados con la minería y con violaciones al derecho al libre tránsito por parte de grupos armados guerrilleros y paramilitares. La violencia contra la mujer es otro problema mencionado por una de las estudiantes consultadas. Algunos de los estudiantes hacen referencia a experiencias negativas que parten de las relaciones que sus padres y abuelos tuvieron en el pasado con los misioneros evangélicos estadounidenses “Nuevas Tribus”[10] y con los salesianos de la iglesia católica.

Los estudiantes entrevistados del pueblo Pumé provienen del estado Apure, una zona de extensos llanos y sabanas.Los problemas más nombrados por los entrevistados están relacionados a la invasión de sus territorios por terratenientes y la violencia de los colonizadores de ayer y la expansión de los hatos y fundos criollos de más de recién data establecidos en las tierras situadas al norte del Capanaparo.

En relación con la presencia de los yukpas en la UIV, la misma está ligada al líder indígena Sabino Romero[11]. Son dos de sus hijos y una de sus hijas quienes han turnado su estadía en la universidad con largos ciclos de permanencia en su comunidad Chaktapa, antigua hacienda Tizina, la cual que fue recuperada por la familia Romero en el 2009. El pueblo yukpa está en el occidente del estado Zulia, específicamente en la Sierra de Perijá y se ha asentado alrededor de las cuencas de los ríos Apón, Negro, Yaza y Tukuko. La misión capuchina “Los ángeles del Tokuko”, ubicada en el centro piloto Tokuko, ha ejercido gran influencia en el destino de ese pueblo hasta el punto de que la comunidad donde se asentó es hoy la de mayor concentración de yukpas en convivencia con criollos venezolanos y colombianos. Fue precisamente en el Tokuko donde Sabino Romero fue ajusticiado.

Los estudiantes del pueblo E ñepá proceden uno de la comunidad Sabanita en el sector Perro de Agua y el otro, fundador de la UIV, de la comunidad Keipon, ambas comunidades en estado Bolívar. Entre las dificultades que hacen referencia están las asociadas al alcoholismo, la pérdida acelerada del idioma debido en parte a que en la escuela primaria se privilegia el idioma español por encima que el Eñepá. También refieren como problema a enfrentar el inicio de la construcción de la central hidroeléctrica Chorrín, proyecto que ha dividido la opinión entre los habitantes de las comunidades directamente afectadas.

Los jóvenes del pueblo Jivi provienen de comunidades semi rurales ubicadas en Guarataro, uno de los municipios del estado Bolívar. Es importante destacar que los Jivi son quizá uno de los pueblos indígenas con mayor índice de desarraigo en comparación con otros pueblos y que se ha visto en la necesidad de migrar hacia otros sectores en busca de tierras para el cultivo.

Resultados y discusión

Espacios de socialización

Los testimonios de los estudiantes permiten identificar espacios para la socialización los siguientes: las residencias estudiantiles, el infocentro, los juegos deportivos y en específico el terreno aplanado que se usa como cancha para jugar futbol. En cada una de estos espacios los estudiantes se agrupan para “escuchar música,” echar broma” o “trabajar a gusto”. La libertad se experimenta de forma más plena en virtud de que no hay presencia de figuras de autoridad. A la par de los mencionados, especial atención merece la música que aparece como un elemento simbólico presente a través de los dispositivos celulares. De igual forma el tiempo libre estipulado en el horario de actividades los sábados luego del medio día y los domingos.

Es importante resaltar que en la interacción de distintas culturas los jóvenes valoran el nacimiento de redes de amistad que se crean a partir de reconocerse a sí mismo en los otros. Uno de los aspectos que más hacen referencia los estudiantes es la oportunidad de poder conocer la diversidad de pueblos indígenas que existen en Venezuela. Javier, del pueblo yukpa comenta que antes de su experiencia en la UIV, él pensaba que sólo existían en Venezuela pueblos indígenas del estado Zulia. Por otra parte, sorprende las valoraciones que cada estudiante hace a partir de las apreciaciones de los otros en función del compartir que se genera en las residencias estudiantiles. Alberto, del pueblo Yekuana expresa que:

Lo que me ha impactado fue, como se llama, los chamos Eñepá, porque ellos son se ven como callados y a la hora de hacer cosas como son directos, van directo al tema y si tú cometiste un error ellos lo discuten en el momento o te llevan para la coordinación para que se pueda resolver. Yo viví un tiempo con ellos. Me dí cuenta de que aunque son callados son muy directos, si son bravos, entonces no te dicen pero a la hora que tienen que decirlo te dicen y eso también me ha enseñado cosas.

José, del pueblo pemon comenta que cuando ingresó a la UIV lo ubicaron en residencias estudiantiles distintas a las de su pueblo. Esta experiencia le permitió conocer a los demás jóvenes

Cuando vine por primera vez sentí que recibieron como en mi casa pues la mayoría de los jóvenes indígenas me aceptaron. Los primeros con los que me relacioné fue con los chirianas, Jivi y Sanema. Me dejaron alojar ahí en mi chinchorro. Aunque tenemos diferentes idiomas, el español me sirvió para comunicarme y no quedarme encerrado en mí mismo. Me quedé un semestre y luego en el otro también con otro pueblo. Los indígenas tenemos una forma de ser que nos hace parecidos. Empecé a tener más confianza y a echar broma, compartir cuentos. Empecé también a aprender palabras de otros idiomas.

Durante la convivencia en las residencias estudiantiles, existen espacios libres de las figuras de autoridad representadas por facilitadores, ancianos o por el coordinador general. Durante la semana están las horas de estudio personalizado, los encuentros que acontecen durante la hora de las tres comidas del día. En las residencias estudiantiles también se abren espacios para la resolución de conflictos que son abordados por todos los integrantes que viven en dicho espacio.

El tiempo libre es empleado para distintas actividades, pero la respuesta más concurrida fue la de buscar a las amistades para compartir, seguida por lavar la ropa en el río y la actividad de “ir a pescar con mis amigos”. Por otra oparte, la forma como la universidad indígena ha estructurad el horario surgió como un aspecto que llama la atención de Rafael, joven yukuana, por cuanto este explica que en su comunidad no existe ningún programador de las actividades para guiar lo que cada quien debe hace; sin embargo él admite que es necesario que en la UIV todos y todas se guien por un horario.

En la universidad indígena nosotros somos jóvenes estudiantes de diferentes pueblos, no solo Yekuana, nosotros somos 8 pueblos aquí. Entonces viendo la diferencia y la diversidad de todos los pueblos es necesario poner normas que nos puedan equilibrar el comportamiento. El Yekuana le gusta despertarse temprano, los adultos, se duerme tarde. El Warao es diferente, el Warao se duerme temprano, y se para temprano temprano también. El Pemón se para, puede tener su diferencia también. Entonces para regular eso es necesario una norma, o sea un horario que es una hora donde todos se puedan despertar, donde todos puedan comer.

Respecto con el uso del tiempo libre, la mayoría de los estudiantes refieren como principal actividad la de buscar a mis amigos para compartir (24), seguida por la de lavar ropa e ir a pescar (Resultados Cuestionario Identidades Juveniles Indígenas en la UIV, 2013).

Durante la observación participante se constató la presencia de un acompañante ruidoso que se activa en medio de reuniones informales entre los estudiantes: el celular como dispositivo para escuchar música. Diferentes géneros musicales comparten la escena a diario, desde raspacanilla, paseándose por el reggaetón hasta el rock romántico, el vallenato y música llanera. El 53% de los estudiantes afirmó tener celular. Para cada uno de los estudiantes entrevistados, la música constituye un referente identitario que lo distingue del otro. Por ejemplo, Alejandro, joven del pueblo Wotuja señala que en su comunidad lo mas que se escucha es “reggaetón y raspacanilla pa lante”, él se ha inclinado por el rock mencionado a la agrupación The Killers y la canción “Here with me”. Igualmente le gusta la música romántica pues se considera un “hombre triste por dentro pero por fuera demuestro alegría”.

Por su parte, Damian, del pueblo Pemon no tuvo dudas al precisar sus gustos musicales agrupados en la música electrónica pues “me aburre mucho la música que escuchan en la comunidad, mucha viene de Brasil y no me gusta, prefiero DJ Tiesto, Simple Plan, Green Day”. Tanto este joven Pemon, como el joven Wotuja comparten un estilo de peinado que también es usual en jóvenes urbanos consumidores de las mismas tendencias musicales. El uso del sweter negro, jeanes muy anchos, el corte de pelo Emo son también el reflejo de una parte de la identidad conectada en el consumo global musical. Todo esto indica la función simbólica de la música que funge como parte de “la socioestética”, categoría empleada por Reguillo y que puede entenderse como “producto de mezclas, préstamos e intercambios que resignifican, en una solución de continuidad , la contradicción”(Reguillo,2012:119). Los géneros musicales consumidos por los estudiantes son en orden de preferencia raspacanilla, vallenato, merengue, joropo, reggaetón, rock, y música romántica (Resultados Cuestionario Identidades Juveniles Indígenas en la UIV, 2013).

Otro espacio es el infocentro, el cual es un módulo de dos pisos dotado con computadoras con acceso a internet. A pesar de que no todos los estudiantes van con frecuencia al infocentro, quienes acuden, afirman hacerlo no solo para hacer sus trabajos sino también para buscar información y hacer uso del facebook. El 32% de los consultados afirma tener cuenta en facebook. Al revisar seis perfiles de seis estudiantes diferentes, se puede constatar la circulación de selfie o autorretratos en distintos lugares de la universidad. El contacto se hace con amistades que se encuentran en sus comunidades o estudiando en las ciudades. Mensajes de amor, amistad, nostalgia predominan, así como comentarios de otras fotografías y saludos en la distancia. Es importante señalar que el facebook también se usa como una forma de hacer circular el orgullo identitario. Esto se pudo constatar en casi todos los perfiles revisados la semana alrededor del 12 de octubre, conocido como Día de la Resistencia Indígena. Muchos de los autoretratos fotográficos estaban acompañados de frases como “soy indígena y luchador”; “orgulloso de mi pueblo” o “100% indígena”, lo que refleja un uso politizado del facebook que debe ser valorado y potenciado. Comenta un joven que

El facebook lo he utilizado para comunicarme con la gente. Eso a veces me lo critican aquí, pero yo les explico que depende porque es cuestión de usarlo bien porque yo lo uso como una herramienta de comunicación, lo utilizo como herramienta de denuncia de lo que reflexiono. Lo que he puesto últimamente ha sido sobre el tema de la comunicación, cómo tiene que ser definida la comunicación desde los indígenas, he puesto este tema a ver qué me dicen y para saber en que andan algunos comunicadores indígenas del mundo.

En cuanto a los deportes, destaca el hecho de que se organizan juegos indígenas que son practicados en ciertos momentos con vestimenta tradicional de cada pueblo. Por su parte, el futbol, es una actividad de alta participación en la UIV y se lleva a cabo en uno de los cuatro terrenos cavados para proyectos de acondicionamiento de piscinas para el cultivo de cachama[12].Los deportes indígenas son propicios para el intercambio entre pueblos, demostrando así cierta competitividad que resulta interesante pues entre bromas se hace referencia a ciertas hegemonías de unos pueblos por sobre otros que se evidencian en comentarios como “los pemones somos los mejores en el futbol aunque estamos ahí ahí con los yekuana, pero los ganadores a ciencia cierta son los Piaroa

(Testimonio de estudiante recogido durante juego de futbol, octubre 2013, nota de campo). Son los sábados por la tarde y en especial los días domingos, una vez que el sol cede, los días que se aprovechan para los juegos deportivos. Mientras se enfrentan los dos equipos, alrededor del terreno se sientan los espectadores a apoyar a sus equipos, entre risas y bromas, transcurre la tarde de deportes. Considera esta investigación que las practicas de futbol en la UIV son los espacios de recreación más vitales y con mayor concurrencia.

Autovaloración sobre quién es joven- estudiante indígena

La condición de ser joven indígena varía según las experiencias de vida de cada estudiante entrevistado. Las definiciones revelan contextos y trayectorias de vida asociadas a la familia, la escuela, su relación con los abuelos y abuelas y la participación en actividades laborales, la mayoría informales. Sin embargo, surgió como categoría común la relacionada al estatus de estudiante, el cual fue considerado como un rasgo importante que mucho tiene que ver en la definición de ser joven indígena. La escuela como agente de socialización es también nombrada por todos los entrevistados como la institución responsable de muchos de los cambios que los jóvenes han experimentado, por cuanto la misma ha sustituido el tiempo que antes los padres, madres y abuelas les dedicaban a los niños. En la encuesta realizada, los estudiantes respondieron que son jóvenes indígenas porque “hago cosas que hacen los jóvenes criollos y los indígenas”; “porque tengo la edad de ser joven” y “porque estudio en la Universidad”. El 64% de los jóvenes reportaron haber estudiado en secundaria con jóvenes indígenas y criollos (Resultados Cuestionario Identidades Juveniles Indígenas en la UIV, 2013).

Juan, del pueblo Wotuja quien se considera así mismo “100% joven indígena” explica lo siguiente:

Claro, los jóvenes de hoy han cambiado mucho a cómo eran antes. Los niños antes sabían cómo era el ritmo de la comunidad, lo respetaban. De niños pasaban a portarse bien como adultos de la comunidad, a trabajar en el conuco, a cuidar de la familia. Eso ya no está. Ahora la escuela los hace jóvenes después y quieren hacer otras cosas. Los padres que le dicen a sus hijos hoy?. Hijo vaya usted para la escuela que yo voy para el conuco, voy de cacería. Entonces el hijo se queda en la escuela y lo atiende una maestra que le habla puro en castellano y no le enseña cosas de la comunidad sino de libros que son criollos”. -Porque los jóvenes indígenas de aquella época desde la niñez ya tenía su formación orientado avanzado comparado con los otros no indígenas el caso de los campesinos los criollos siendo el joven, ya desde niño tenia la orientación de sus padres claro eso no dificultaba si el enfrentaba todas sus cosas.

Su apreciación coincide con la de Isamel, Eñepá, quien manifiesta que algunos jóvenes “no hacen mucho trabajo en la comunidad sino que se preocupan de vivir por su propia cuenta. Eso ocurre sobre todo en los jóvenes que han estudiando más o menos desde sexto grado hasta el segundo año en escuelas criollas. Ellos estudian a veces con jóvenes criollos y aprenden a no participar en trabajos comunitarios. Les da pena si son mujeres dicen que no es trabajo de los jóvenes y que ellas no van a hacer lo que hacen los mayores”.

Este comentario revela la influencia de las aspiraciones hegemónicas en las trayectorias de vida de los jóvenes indígenas. Los proyectos de vida individual, muy presente como metas en los jóvenes no indígenas, son asumidos también por los indígenas. Esto incide en el debilitamiento de los tejidos comunitarios y en la fragmentación de las prácticas colectivas de los pueblos indígenas.

El testimonio proveniente de Félix, Yekuana, vincula la juventud con el compromiso de defender su pueblo. Está conectado con la necesidad de manejar temas que las generaciones que le antecedieron no manejaban. Félix, es estudioso del tema de demarcación. Es padre de familia y fue el primer coordinador indígena que tuvo la universidad. “Yo me considero indígena Yekuana, o sea con mucha fuerza, con mucha claridad y eso es primero. Para mi ser joven indígena Yekuana es un orgullo pues, el fruto de la resistencia. Si nosotros los jóvenes no nos preparamos entonces como van a quedar nuestros pueblos? Van a quedar otra vez aplastados”

José, comenta que “nunca he perdido tiempo como joven desde mi juventud siempre he hecho cosas útiles. Hay siempre que aprovechar en la Gran Sabana, en la selva se pueden hacer cosas. Soy joven Pemón y tengo que aprovechar que tengo fuerza para hacer cosas”.

Por su parte Rafael, precisa que es joven indígena porque “soy hijo de la comunidad de Tencua y soy hijo también de Yekuanas conocedores de la cultura y mi mamá también es Yekuana. Y eso me hace ser Yekuana, me siento orgulloso de ser Yekuana. Y eso me hace sentir como, como indígena”. Resulta interesante saber que este joven tiene esposa pero aun no tiene hijos. Al ser interrogado sobre el por qué, él contesta que “aun no lo hemos decidido. Habrá tiempo de tener hijos, y eso será cuando no tenga muchas responsabilidades ya sea aquí o en otra parte”. El ser joven estudiante le permite a Rafael, el poder de aplazar su rol de padre. El acto de estudiar en la UIV es tomado en cuenta por este joven como una de las responsabilidades que más pesa en este momento de su vida y que lo lleva a decidir que no es el momento de convertirse en padre de familia. Rafael hace uso de métodos anticonceptivos para evitar que su esposa quede embarazada. Desde la vivencia de jóvenes urbanos, el tener hijos no resulta compatible con el hecho de estar cursando alguna carrera universitaria. Es bien conocido el consejo de estudiar primero para luego poder tener los medios de mantener a la familia. Por ello, se puede afirmar que el ser joven indígena para este muchacho representa también la posibilidad de tomar desde lo juventud hegemónica, este arreglo que le permite tener tiempo para dedicarse a sus estudios. Por su parte, Alejandro, afirma que

Soy un joven que aprende todos los días en Universidad. Me gusta las fiestas también y como aun no estoy casado aprovecho del tiempo aquí para pintar, me gusta pintar, los indígenas somos muy buenos artistas”. Wiliam, del mismo pueblo pero de otra comunidad se define como joven y a su vez “mestizo” porque “mi mama y mi familia es Piaroa y mi papa es colombiano. Por ahora siento orgullo de ser indígena y como joven rescatar la cultura, tener la experiencia de lo que vivieron mis abuelos, saber que hacían, cómo pasaban la vida.

Del pueblo Eñepá, Ricardo, manifiesta su concepción de joven indígena como “la edad para poder ayudar más a la comunidad” en virtud de que a partir de los 12 años “los Eñepá empezamos a trabajar 15 o 16 años para arriba el Eñepá para arriba comienza a trabajar pero no solo en la familia, o a los padres sino en el campo para todos”. David Palmar[13], es del pueblo Wayú y explica que

Me defino un joven indígena que le apuesta a la pervivencia de los seres vivos y la ética planetaria. Desde la perspectiva occidental el ser joven implica ser una persona que tiene presiones por ser objeto de expectativas sociales. Y eso lo vivo también yo como indígena. Es un vaivén de desaprobaciones como por ejemplo “los wayuu no hacen esto o aquello”, “no pareces Wayuu”. Muchas de estas desaprobaciones vienen también de tu misma gente. Es una carga doble de expectativas. Hay romanticismo de que los ancianos son quienes tienen la verdad absoluta. Pero hay situaciones en las que hay que hacer una lectura muy compleja.

Lo narrado por David revela la doble carga que tienen los jóvenes indígenas en la construcción que otros hacen sobre ellos y ellas. Por ello “la forma de autonombrase en las diferentes adscripciones identitarias (…) ha desempeñado un papel muy importante no solo en relación con las formas de comunicación entre pares, sino con respecto a los diversos modos en que se posiciona ante la sociedad” (Reguillo, 2012: 99).

Es de singular importancia algunas valoraciones que estos estudiantes indígenas hacen de los jóvenes criollos. En todos los testimonios surgieron episodios de racismo y sentimientos de superioridad por parte de los criollos. El 89% de los estudiantes indígenas considera que los jóvenes criollos y los indígenas son diferentes. Las reflexiones que se desprendieron a partir de las interrogantes si te consideras joven indígena y por qué, surgen también de precisar las diferencias en relación con el joven criollo. Así Eduardo, del pueblo Pumé relata que

Lo que yo he visto, no sé, los criollos siempre han sido, han visto, ven a los indígenas como muy inferiores, ellos creen así no, y dicen que los indígenas no saben nada pero viendo eso yo me he preguntado en mi personal, y los pumé somos iguales, pensamos iguales, lo que pasa. Los criollos utilizan una palabra. Que el indígena “pluma”. Esa es la palabra que usan. Pero entonces en mi interpretación, he analizado así no, y pluma significaría que no vale, no. Ello sería carne y el indígena pluma que no vale.

Las experiencias de racismo han estado muy presentes en las escuelas primarias y secundarias donde las clases se comparten con estudiantes criollos. Adedukawa narra que “en el colegio la Guanota Fe y Alegría Apure. Porque allá los campesinos, los criollitos estaban acostumbrados a joder a los indígenas “mira, indio” los Yekuana siempre hemos sido talento en el futbol, jugamos más que los criollos, que aquellos entonces nos envidiaban y uno se sentía, bueno no sé porque uno no se burla sino que es la realidad y bueno cuando nosotros estábamos en la cancha jugábamos los mejores entonces nos envidiaban “indio come lombriz, come casabe, come mañoco” entonces una vez lo agarré. Peleamos ahí y hasta ahí pues” De hecho, 70% de los estudiantes afirmaron el haber sufrido alguna forma de racismo en sus vidas. Y en cuanto a las relaciones con los jóvenes criollos, el 53% afirman que entre los indígenas y no indígenas “no se relacionan mucho” y un 23% expresó que las peleas son porque los jóvenes criollos se creen más que los jóvenes indígenas (Resultados Cuestionario Identidades Juveniles Indígenas en la UIV, 2013).

Alberto, cuanta que existe mucha competencia entre los criollos e indígenas. Así narra que

En un liceo básicamente criollo donde él cursaba estudios junto con dos primos nos decían que esos indígenas no saben nada eso me ha arrechado mucho a mí me ponía molesto como éramos chamos paso una vez nos caímos a coñazos después, ellos se creían más y no era verdad porque nosotros decíamos vamos a estudiar a ver qué tal vamos a medirnos en el estudio y nos mediamos también en las matemáticas.

Muchos de los estudiantes observan como principal diferencia entre los jóvenes criollos es que los indígenas “saben hacer más cosas”, juegan mejor el futbol, tienen más habilidades y destrezas como por ejemplo correr en la selva, cazar, pescar. En este sentido, Rafael afirma que los jóvenes criollos de la secundaria “primero no saben hacer su comida (…) segundo, nosotros hacíamos una cosa como pequeña que es difícil para ellos que es peluquearnos, o sea simplemente con una tijera y ya se hace un corte. Y ahí es donde eso sorprendía. Bueno, son prácticas. Nosotros sabemos hacer eso. En el deporte también siempre ganábamos los indígenas. Entonces y se ha visto mucho eso la competencia también.

Los estudiantes yukpas consultados, son entre todos los de la universidad, quienes más cerca han experimentado el racismo, la discriminación y la injusticia. No solo en los términos de la lucha cuerpo a cuerpo contra los terratenientes, sino desde la escuela de “los curas” en donde estuvieron internados para aprender a leer y escribir bien. Javier recuerda que

Cuando yo estudié pues en la escuela de la misión del Tokuco que se llamaba Unidad Educativa Sagrada Familia, fundada desde muchos tiempos por los curas, entonces como mi papá Sabino pues ha luchado o ha tenido muchos tiempo de lucha entonces ya nos tenían señalados entre los ganaderos ,entonces bueno nosotros como los hijos del cacique Sabino alli pues nos trataban mal , nos castigan mucho y que a barrer eso o limpiar cosas feas, podridas pues, como por ejemplos los excrementos de perros, a botar basura que tenía mucho tiempo. El padre Eduardo y el padre que es español y el padre Sandoval y que es de Caracas, y el padre español Víctor, este ellos decían siempre cuando yo estoy haciendo ya cuarto grado yo lo escuchaba cuando estaba diciendo que si mi papa seguía con la lucha nos iban a sacar; decían ellos, los curas decían ellos pues, que tenían que sacar a los hijos de Sabino, nos amenazaban con los estudios pues, nos amenazaban decían que tenían que cansarnos para que nos fuéramos de la escuela (…)porque ellos nos decían que nuestro padre estaba haciendo malas cosas; también nos decían que teníamos que aprender mucho sobre la religión como hijo de Sabino (…) y que nuestra cultura eso ya no valía pues porque ya hasta si hablamos asi pues en nuestro idioma ellos decían que nuestro idioma no existía (…) nos juntábamos con los muchachos de Toromo a echar cuentos en yukpa pero los curas querían siempre que uno este leyendo eso de lo que dicen biblia sino, nos decían que es importantísimo de estar diariamente rezando por el único dios que ellos tienen no sé donde.

Ismael narra que en la secundaria algunos estudiantes criollos provocaban a los jóvenes indígenas para “poner bravos a esos indios”. Pero ese “indio” tiene nombre. Igualmente recuerda comentarios como “los indios no son de aquí venezolanos”. Yo les decía que mira chamo ustedes tienen sangre indígena, y ellos se reían que va chamo yo no soy indio”. Sin embargo, a pesar de esto, Najté con orgullo también recuerda que hizo equipo en algunos cursos con un estudiante Piaroa porque “era bueno en matemática y que “cuando el profesor me mandaba a sacar el problema de la física” los demás estudiante s criollos buscaban anotarse con ellos para hacer equipo.

Atendiendo a los testimonios citados, se considera que los estudiantes de la UIV, todos con experiencias diferentes, han construido simbólicamente un nosotros, que somos jóvenes indígenas estudiantes, como terreno de representaciones que les es común a todos y todas. Podría afirmarse que existe también una identidad colectiva a partir del encuentro de las diferentes identidades individuales, las historias colectivas de los pueblos y las vivencias de racismo y discriminación que le son comunes a todos los entrevistados. Se debe aclarar este aspecto porque no se trata de afirmar que sea una identidad colectiva que hace que todos sean iguales. Lo que acontece es que se afianza “el carácter relacional” de la identidad como proceso de “identificación- diferenciación” con relación a un Otro criollo que refleja en su relación con el Otro indígena su cognitivo de racismo.

Valoración de la Universidad Indígena para la reafirmación cultural

En lo relativo el rol que ocupa la UIV la vida de los estudiantes, vale la pena por conocer lo afirmado por Ricardo, Eñepá.

Yo me hice más consiente aquí en la Universidad. Los criollos piensan mal de uno. Los criollos dicen por qué estudian los indígenas?. Los pueblos indígenas estudian por su vida, por su comunidad (…)aquí estudié sin dejar de dedicarme a la producción de arroz de mi comunidad

Los jóvenes reflejan un sentido de pertenencia a la Universidad Indígena que viene dado desde un lugar que “señala un camino” en frases como que “la universidad me ha cambiado (…) me trajo otra vez a mi lugar porque yo estaba yendo a otro lado”. Ese “otro lado” al que hace referencia uno de los estudiantes Yekuana quien experimentó dos años la experiencia de estar en una universidad nacional, siendo él solo el único indígena, implica la transición entre un camino que escogió pero que luego de experimentarlo decidió “el regreso” que lleva en sí la posibilidad para la realización personal resignificada a partir de la valoración de su identidad indígena. Esta no niega en este joven el poder, por ejemplo, de escoger estudiar comunicación social en la Universidad Indígena, manejar programas avanzados de edición de videos y diseño gráfico, al mismo tiempo poseer cuenta de facebook y tener contacto con el mundo a través de esta red digital.

Hasta el momento, muchos elementos indican que la Universidad es apreciada porque involucra espacios para la libertad identitaria y la posibilidad de pertenecer a un proyecto que da sentido a la existencia de estos jóvenes.Alejandro, cuenta que luego de la muerte de su padre “me quise suicidar yo me sentía que no servía, fumaba mucha marihuana, no sabía qué hacer”.Hay un antes y un después en la vida de los estudiantes. Narra Rafael que “en un momento llegué a pensar de querer ser salesiano. Porque yo estuve con los salesianos 6 años. Después pensé estudiar, mirando la universidad pensé estudiar veterinaria y conseguir trabajo por lo menos en una hacienda y vivir.

En palabras del profesor y co fundador de la UIV, Hernán González, al ser la universidad una expresión de “identidades geohistóricas que constituyen cada pueblo indígena”, las relaciones interculturales que incluyen no solamente la relación entre una cultura indígena determinada y la hegemónica sino que también, las relaciones entre estudiantes de distintos pueblos, genera espacios que nutren los modos de ser individuales que se encuentran en un espacio colectivo y que son el fruto de un “proceso permanente de resemantización y enriquecimiento a través de las relaciones de interculturalidad”.( Entrevista a Hernán González, 2013)

Aquí se toma conciencia, aquí se está preparando generación de jóvenes, digamos asumiendo una identidad y estamos tomando conciencia y no echarnos para taras como doce alguna gente criolla. La idea es que nosotros los indígenas nos prepararemos a partir de nuestra cultura en primer lugar, pero también tomando las herramientas que nos ofrece la cultura occidental, lo necesario. Por eso yo agradezco mucho al Hermano Korta en Yarikajé[14], me cambió porque fue un espacio donde reflexioné profundamente a partir de por qué fuimos maltratados, escuché sobre el genocidio, exterminio. Nos decía que ustedes son valiosos, ustedes son seres humanos, ustedes no son animales, echa para adelante tu pueblo va a seguir siendo marginado por la cultura criolla si no valoras tu cultura.

Adedukawa quien ya finalizó sus estudios en la UIV y cumplió su labor como coordinador indígenas en más de una ocasión ratifica que

Cuando llego allá [a Yarikajé su comunidad] siento que estoy preparado. Al escuchar la gente, una reunión, un análisis, un debate, te convierte como una persona que puede conducir, cuando… Después cuando hay conflictos, tú eres la persona adecuada. Entonces cuando yo digo “esta es la propuesta” entonces todo el mundo en ambas partes dice ok.

Los procesos cotidianos de gestión de la Universidad son llevados a cabo por un equipo de coordinadores indígenas electos en asamblea cada dos años. Se aborda desde lo académico, las áreas demostrativas, el reporte de daños en infraestructura, las compras de la comida en los poblados más cercanos, el seguimiento del estado de las residencias estudiantiles. Por otro lado, los estudiantes han tenido un acercamiento importante con organizaciones indígenas que han visitado la universidad, luchadores como David Copenhague del pueblo Yanomami; Amil del Pueblo Paltier Suruí, la asistencia a reuniones con los aliados, atención de invitaciones eventos nacionales e internacionales relacionados a temas de educación y derechos territoriales y culturales de los pueblos indígenas. En lo simbólico, la Universidad ratifica en sus espacios y en los temas impartidos su lugar como institución comunitaria en permanente autoafirmación de su carácter emancipador. Najte comenta que “yo me acuerdo del año 2008 en donde yo estudiaba, los profesores no se preocupaban mucho a dar clases de donde esta historia de los pueblos indígenas”. En la UIV la historia colectiva de estos pueblos cobra fuerza como proyecto político “constituyendo una esfera autónoma y especializada, que adquiere corporeidad en las practicas cotidianas de los actores, en los intersticios que los poderes no pueden vigilar” (Reguillo 1997 citada por Reguillo 2012:36).

En relación a lo antes expuesto conviene precisar dos eventos que acontecen anualmente: la semana de la sabiduría indígena y la semana de la resistencia indígena. En el primero, cada comunidad estudiantil debe convocar a ancianos y ancianas de sus comunidades quienes hacen acto de presencia en la Universidad por una semana, la cual se organiza de tal manera que permita que estos abuelos vayan a la selva con los jóvenes a intercambiar historias, reflexiones, prácticas. El segundo, organizado alrededor del 12 de Octubre, menos íntimo que la semana de la sabiduría, incorpora visitantes de otros países, así como a activistas sociales, profesores de distintas casa de estudios. La semana de la resistencia finaliza con reflexiones que son compartidas en la “churuata ateneo”.

Para Eduardo, Pumé, “la universidad es netamente indígena y es una oportunidad para los pueblos originarios que nunca tuvieron nuestros abuelos y hoy si los tenemos. Antes no tuvimos oportunidad entonces eso sería no, como un, eso seria. La esperanza de los pueblos indígenas (…) he aprendido muchas cosas que no sabía en la comunidad. Tati, por su parte opina que

He tenido reflexión sobre el pueblo Pumé por mi parte la universidad indígena es muy importante porque aquí se conoce la diversidad de cultura y aprendes a través de la reflexión por lo menos a través del cine foro que cuando uno está viendo se ve uno mismo y llama la atención sobre la lucha que están haciendo los indígenas en otros países y comparando en eso pues es muy importante la universidad indígena que nos brinda la oportunidad seguir conociendo esas realidades.

Atendiendo las voces citadas, la Universidad Indígena se erige como un espacio interiorizado con sentido de pertenencia en cada estudiante. Las distintas maneras de significar la Universidad nos habla de un sentido de protección, reafirmación identitaria, posibilidad de organizarse como sujetos políticos a través del entendimiento de las causas de exclusión social y material de las comunidades a las que pertenecen estos estudiantes. Cobran sentido sus experiencias en el contexto de la Universidad a partir de las discusiones colectivas de la realidad nacional y las tensiones históricas entre el estado venezolano y los pueblos indígenas

Yo crecí escuchando de Tauca. A mí no me lo explicaba mi papa pero le explicaba era a mi mamá. Como nosotros dormimos siempre juntos, o sea nosotros no tenemos cuarto. Mi papa se acostumbró así, una casa grande para todos, duermen todos y toda la conversación se escucha, en las mañanas. Y yo crecí escuchando que Tauca era un sitio donde estaban los jóvenes estudiando, los jóvenes indígenas, que aprendían a escribir en su idioma, también aprendían a manejar computadoras, aprendían a expresarse, hablar bien, también profundizaban los conocimientos de su cultura y claro . Y bueno eso fue así, lo que yo escucho sobre la Universidad. Yo tendría como 7-8 años.

Un joven E ñepá afirma que

Me entere de la UIV por Korta al salir del 3er año quería estudiar electricidad pero mi papa no quería él quería que estudiara medicina pero no pude pagar los viajes para inscribirme y perdí la inscripción. Me case de esperar. Fue cuando decidí hablar con mi papa para irme a la UIV porque no ponían trabas ni me pedían papeles. Mi papa y mi tio como autoridades de la comunidad nos dieron el permiso a 5 a los que éramos mayores de edad para ver cómo era eso de la UIV. Como cuando Korta fue a la granja a hacer la promoción y yo me acuerdo cuando Korta se sentó en la mesa donde yo estaba y me preguntó qué etnia yo pertenecía le dije “soy Eñepa” y me pregunto la comunidad. Yo equivocadamente le dije que Caicara, claro, teníamos casa allá pero Korta me corrigió y me dijo “no, que Caicara no hay Eñepa!” que en Caicara están los criollos, entonces me sentí así como que en verdad no era así como lo que yo estaba diciendo”

Las incertidumbres que con fuerza están presente en la vida de los jóvenes indígenas, en la Universidad pasan a un terreno donde crece la posibilidad de ubicar respuestas. Al ser la Universidad un lugar identificado de antemano por los padres y ancianos de las comunidades, les permite a los estudiantes incorporarse con mayor confianza. José, de la comunidad Pemon Mapaurí, coincide con otros entrevistados en el hecho de que la Universidad “le sembró su conciencia” pues “aunque yo internamente tenía interés por mi cultura, en la escuela no se hablaba mucho (…) se hablaba de básico, la historia, cómo fue la conquista, pero no se profundizaba (…)el maestro o el profesor indígena de hoy, no se preocupan por los estudiantes jóvenes (…) estos buscan después formarse como profesionales en la vida pero a favor de una cultura dominante, es un a critica pues que yo hago” (…)desde que estoy aquí yo pienso, dialogo con la cultura dominante, esto es como un objetivo de la universidad”

Se puede afirmar así la Universidad como un territorio de anclaje para estos jóvenes. No solamente porque hay similitudes en la pertenencia de clase, sino por y sobre todo, se comparte en lo profundo el pertenecer a una población racializada en los términos de la colonialidad del poder. La Universidad se establece como una respuesta a un problema el cual “radica en la traducción de la discriminación racial al estatuto de políticas públicas que cierra la pinza de un imaginario que la modernidad no logró erradicar: el de una superioridad anclada en la diferencia racial, también llamada ‹supremacía›” (Reguillo 2002:152)

Cuando estamos en clase, los compañeros que tienen más conciencia y viven la realidad, buscan, tratan de que el estado abra los ojos para que también se sepa la realidad de los pueblos indígenas. Por ejemplo, el problema de la minería, veo algunos de los compañeros que sienten la realidad y discuten el mismo problema y allí se ve la importancia de que los estudiantes deban unir un solo pensamiento para buscar un fin determinado y decirle a las instituciones que esto está pasando.

En contraposición de la UIV, Kepler, estudiante Pemon de una universidad en Caracas argumenta que

El sistema educativo [universidades criollas] está diseñado desde mi punto de vista para crear empleados, por lo que le importan nada si eres o no un joven indígena. Lo que les interesa es que compitan entre sí generando en muchos estudiantes ambiciones desmedidas, y en algunos casos rompimiento de valores, muy pocas universidades si educan a sus estudiantes a ser emprendedores, por ende, que se puede esperar de estas casas de estudio donde lo más importante es si logras calcar, memorizar toda la información eres parte del sistema.

El ubicarse como joven indígena en contextos sociales donde predominan los no indígenas implica para los entrevistados el correcto uso del idioma castellano, al mismo tiempo del idioma propio; la capacidad para escribir y liderar procesos de organización y en los casos donde la discriminación cabalga, una forma irreductible es la demostración de la fuerza física, ya sea en los deportes o ante enfrentamiento cuerpo a cuerpo. En la Universidad Indígena 94% de los estudiantes afirmó hablar bien el idioma y el 77 % lo escribe y la pregunta ¿cómo haces para manejarte en la interculturalidad?, el 65% expresa el manejo correcto tanto del español como del idioma propio, seguido por el uso de la vestimenta (Resultados Cuestionario Identidades Juveniles Indígenas en la UIV, 2013)

Felix expresa que “es importante que los indígenas en esta universidad aprendamos a utilizar la escritura, eso es fundamental, y que aprendamos a usar las computadoras, es necesario”. Para este joven la escritura también en una forma de poder registrar la palabra de los ancianos entonces, así