By Joan Pedro-Carañana

Trump’s brand of populism and politics are a tragedy for democracy and a triumph for authoritarianism. Using manipulation, misrepresentation and a discourse of hate, he is pushing policies designed to destroy the welfare state and the institutions that make a democracy possible. Trump’s first few months in office offer a terrifying glimpse of an authoritarian project that combines the ruthlessness of neoliberalism with an attack on historical memory, critical agency, education, equality and truth itself. While the US may not be in the full bloom of the fascism of the 1930s, it is at the tipping point of a virulent, American-style authoritarianism. These are truly dangerous times as right-wing extremists continue to move from the margins to the center of political life.

I asked renowned public intellectual and social activist Henry Giroux — who has written extensively on cultural studies, youth studies, popular culture, media studies, social theory and the politics of higher and public education — to discuss the new developments that are taking place in the United States and the possible strategies and tactics to engage successfully in processes of resistance and egalitarian social transformation during the Trump era. In this interview, he analyzes the underlying forces of authoritarianism at work in the United States and Europe, and argues that resistance is not simply an option but a necessity.

Let’s begin by discussing the current state of US politics and then move on to looking at the alternatives for change. What is your evaluation of the first two months of Trump’s presidency?

The first two months of Trump’s presidency fit perfectly with his deeply authoritarian ideology. Rather than being constrained by the history and power of the presidency as some have predicted, Trump unapologetically embraced a deeply authoritarian ideology and politics that was evident in a number of actions.

First, at his inaugural address he echoed fascist sentiments of the past by painting a dystopian image of the United States marked by carnage, rusted-out factories, blighted communities and ignorant students. Underlying this apocalyptic vision was the characteristically authoritarian emphasis on exploiting fear, the call for a strong man to address the nation’s problems, the demolition of traditional institutions of governance, an insistence on expanding the military, and an appeal to xenophobia and racism in order to establish terror as a major weapon of governance.

Second, Trump’s support for militarism, white nationalism, right-wing populism and a version of neoliberalism on steroids was made concrete in his various cabinet and related appointments, which consisted mostly of generals, white supremacists, Islamophobes, Wall Street insiders, religious extremists, billionaires, anti-intellectuals, incompetents, climate-change deniers and free-market fundamentalists. What all of these appointments share is a neoliberal and white nationalist ideology aimed at destroying all of those public spheres, such as education and the critical media that made democracy function, and political institutions, such as an independent judiciary. They are also united in eliminating policies that protect regulatory agencies and provide a foundation for holding power accountable. At stake here is a united front of authoritarians who are intent on eroding those institutions, values, resources and social relations not organized according to the dictates of neoliberal rationality.

Third, Trump initiated a number of executive orders that left no doubt that he was more than willing to destroy the environment, rip immigrant families apart, eliminate or weaken regulatory agencies, expand a bloated Pentagon budget, destroy public education, eliminate millions from health care insurance, deport 11 million unauthorized immigrants from the United States, unleash the military and police to enact his authoritarian white nationalist agenda, and invest billions in building a wall that stands as a symbol of white supremacy and racial hatred. There is a culture of cruelty at work here that can be seen in the Trump administration’s willingness to destroy any program that may provide assistance to the poor, working and middle classes, the elderly and young people. Moreover, the Trump regime is filled with war mongers who have taken power at a time in which the possibilities of nuclear wars with North Korea and Russia have reached dangerous levels. Furthermore, there is the threat that the Trump administration will escalate a military conflict with Iran and become more involved militarily in Syria.

Fourth, Trump repeatedly exhibited a shocking disrespect for the truth, law and civil liberties, and in doing so he has undermined the ability of citizens to be able to discern the truth in public discourse, test assumptions, weigh evidence and insist on rigorous ethical standards and methods in holding power answerable. Yet Trump has done more than commit what Eric Alterman calls «public crimes against truth.» Public trust collapses in the absence of dissent, a culture of questioning, hard arguments and a belief that truth not only exists but is also indispensable to a democracy. Trump has lied repeatedly, even going so far as to accuse former President Obama of wiretapping, and when confronted with his misrepresentation of the facts, he has attacked critics as purveyors of fake news. Under Trump, words disappear into the rabbit hole of «alternative facts,» undermining the capacity for political dialogue, a culture of questioning and civic culture itself. Furthermore, Trump not only refuses to use the term «democracy» in his speeches, he is also doing everything he can to establish the foundations for an overt authoritarian society. Trump has proven in his first few months in office that he is a tragedy for justice, democracy and the planet and a triumph for an American style proto-fascism.

You have argued that contemporary societies are at a turning point that is bringing the rise of a new authoritarianism. Trump would only be the tipping point of this transformation?

Totalitarianism has a long history in the United States and its elements can be seen in the legacy of nativism, white supremacy, Jim Crow, lynchings, ultranationalism and right-wing populist movements, such as the Ku Klux Klan and militiamen that have been endemic to shaping American culture and society. They are also evident in the religious fundamentalism that has shaped so much of American history with its anti-intellectualism and contempt for the separation of church and state. Further evidence can be found in the history of corporations using state power to undermine democracy by smashing labor movements and weakening democratic political spheres. The shadow of totalitarianism can also be seen in the kind of political fundamentalism that emerged in the United States in the 1920s in the Palmer raids and in the ’50s with the rise of the McCarthy period and the squelching of dissent. We see it in the Powell Memo in the 1970s and in the first major report of the Trilateral Commission called The Crisis of Democracy, which viewed democracy as an excess and threat. We also saw elements of it in the FBI’s COINTELPRO program, which infiltrated radical groups and sometimes killed their members.

In spite of this sad legacy, Trump’s ascendency represents something new and even more dangerous. No president in recent memory has displayed such blatant disregard for human life, abolished the distinction between truth and fiction, surrounded himself so overtly with white nationalists and religious fundamentalists, or exhibited what Peter Dreier has described as a «willingness to overtly invoke all the worst ethnic, religious, and racial hatreds in order to appeal to the most despicable elements of our society and unleash an upsurge of racism, anti-Semitism, sexual assault, and nativism by the KKK and other hate groups.»

Conservative commentator Charles Sykes is right in arguing that the administration’s «discrediting independent sources of information also has two major advantages for Mr. Trump: It helps insulate him from criticism and it allows him to create his own narratives, metrics and ‘alternative facts.’ All administrations lie, but what we are seeing here is an attack on credibility itself.» In a terrifying signal of his willingness to discredit critical media outlets and suppress dissent, he has gone so far as to label the critical media as the «enemy of the people,» while his chief strategist, Stephan Bannon, has called them the «opposition party.» He has attacked — and in some cases fired — judges who have disagreed with his policies. Meanwhile he has threatened to withdraw federal funds from universities that he thought were largely inhabited by liberals and leftists, and he has embraced alt-right conspiracy theories in order to attack his opponents and give legitimacy to his own flights from reason and morality.

What must be acknowledged is that a new historical conjuncture emerged in the 1970s when neoliberal capitalism began to wage an unprecedented war against the social contract. At that time, elected officials implemented austerity programs that weakened democratic public spheres, aggressively attacked the welfare state and waged an assault on all of those institutions crucial to creating a critical formative culture in which matters of economic justice, civic literacy, freedom and the social imagination are nurtured among the polity. The longstanding contract between labor and capital was torn up as politics became local. Power ceased being bounded by geography and became embedded in a global elite with no obligations to nation states. As the nation state weakened, it was reduced to a regulatory formation to serve the interest of the rich, corporations and the financial elite. The power to get things done is no longer in the hands of the state; it now resides in the hands of the global elite and is managed by markets.

What has emerged with the rise of neoliberalism is both a crisis of the state and a crisis of agency and politics. One consequence of the separation of power and politics was that neoliberalism gave rise to massive inequalities in wealth, income and power, furthering a rule by the financial elite and an economy of the 1%. The state was not able to provide social provisions and has rapidly been reduced to its carceral functions. That is, as the social state was hollowed out, the punishing state increasingly took over its obligations. Political compromise, dialogue and social investments gave way to a culture of containments, cruelty, militarism and violence.

The war on terror further militarized American society and created the foundation for a culture of fear and a permanent war culture. War cultures need enemies and in a society governed by a ruthless notion of self-interest, privatization and commodification, more and more groups were demonized, cast aside and viewed as disposable. This included poor Blacks, Latinos, Muslims, unauthorized immigrants, transgender communities and young people who protested the increasing authoritarianism of American society. Trump’s appeal to national greatness, populism, support for state violence against dissenters, a disdain for human solidarity and a longstanding culture of racism has a long legacy in the United States, and was accelerated as the Republican Party was overtaken by religious, economic and educational fundamentalists. Increasingly, economics drove politics, set policies and put a premium on the ability of markets to solve all problems, to control not only the economy but all of social life. Under neoliberalism, repression became permanent in the US as schools, the local police, were militarized and more and more, everyday behaviors, including a range of social problems, were criminalized.

In addition, the dystopian embrace of an Orwellian control society was intensified under the umbrella of a National Security State, with its 17 intelligence agencies. The attacks on democratic ideals, values, institutions and social relations were accentuated through the complicity of apologetic mainstream media outlets more concerned about their ratings than about their responsibility as constitutive of the Fourth Estate. With the erosion of civic culture, historical memory, critical education and any sense of shared citizenship, it was easy for Trump to create a corrupt political, economic, ethical and social swamp. Trump must be viewed as the distilled essence of a much larger war on democracy brought to life in late modernity by an economic system that has increasingly used all the ideological and repressive institutions at its disposable to consolidate power in the hands of the 1%. Trump is both a symptom and accelerant of these forces and has moved a culture of bigotry, racism, greed and hatred from the margins to the center of American society.

What would be the similarities and the differences in regard to past forms of authoritarianism and totalitarianism?

There are echoes of classical fascism of the 1920s and 1930s in much of what Trump says and how he performs. Fascist overtones resound as Trump taps into a sea of misdirected anger, promotes himself as a strong leader who can save a nation in decline and repeats the fascist script of white nationalism in his attacks on immigrants and Muslims. He also flirts with fascism in his call for a revival of ultranationalism, his discourse of racist hate, his scapegoating of the «other,» and his juvenile tantrums and tweet attacks on anyone who disagrees with him. His use of the spectacle to create a culture of self-promotion; his mix of politics and theater mediated by an emotional brutality; and a willingness to elevate emotion over reason, war over peace, violence over critique, and militarism over democracy.

Trump’s addiction to massive self-enrichment and the gangster morality that informs it threatens to normalize a new level of political corruption. Moreover, he uses fear and terror to demonize others and to pay tribute to an unbridled militarism. He has surrounded himself with a right-wing inner circle to help him implement his dangerous policies on health care, the environment, the economy, foreign policy, immigration and civil liberties. He has also expanded the notion of propaganda into something more perilous and lethal for a democracy. A habitual liar, he has attempted to obliterate the distinction between the facts and fiction, evidence-based arguments and lying. He has not only reinforced the legitimacy of what I call the «disimagination machine,» but also created among large segments of the public a distrust of the truth and the institutions that promote critical thinking. Consequently, he has managed to organize millions of people who believe that loyalty is more important than civic freedom and responsibility. In doing so he has emptied the language of politics and the horizon of politics of any substantive meaning, contributing to an authoritarian and depoliticized culture of sensationalism, immediacy, fear and anxiety. Trump has galvanized and emboldened all the antidemocratic forces that have been shaping neoliberal capitalisms across the globe for the last 40 years.

Unlike the dictators of the 1930s, he has not set up a secret police, created concentration camps, taken complete control of the state, arrested dissenters or developed a one-party system. Yet, while Trump’s America is not a replica of Nazi Germany, it expresses elements of totalitarianism in distinctly American forms. Hannah Arendt’s warning that rather than being a thing of the past, elements of totalitarianism would more than likely, in mid-century, crystallize into new forms. Surely, as Bill Dixon points out, «the all too protean origins of totalitarianism are still with us: loneliness as the normal register of social life, the frenzied lawfulness of ideological certitude, mass poverty and mass homelessness, the routine use of terror as a political instrument, and the ever growing speeds and scales of media, economics, and warfare.» The conditions that produce the terrifying curse of totalitarianism seem to be upon us and are visible in Trump’s denial of civil liberties, the stoking of fear in the general population, a hostility to the rule of law and a free and critical press, a contempt for the truth, and this attempt to create a new political formation through an alignment of religious fundamentalists, racists, xenophobes, Islamophobes, the ultrarich and unhinged militarists.

What are the connections between neoliberalism and the emergence of neo-authoritarianism?

For the last 40 years, neoliberalism has aggressively functioned as an economic, political and social project designed to consolidate wealth and power in the hands of the upper 1%. It functions through multiple registers as an ideology, mode of governance, policy-making machine, and a poisonous form of public pedagogy. As an ideology, it views the market as the primary organizing principle of society while embracing privatization, deregulation and commodification as fundamental to the organization of politics and everyday life. As a mode of governance, it produces subjects wedded to unchecked self-interest and unbridled individualism while normalizing shark-like competition, the view that inequality is self-evidently a part of the natural order, and that consumption is the only valid obligation of citizenship. As a policy machine, it allows money to drive politics, sells off state functions, weakens unions, replaces the welfare state with the warfare state, and seeks to eliminate social provisions while increasingly expanding the reach of the police state through the ongoing criminalization of social problems. As a form of public pedagogy, it wages a war against public values, critical thinking and all forms of solidarity that embrace notions of collaboration, social responsibility and the common good.

Neoliberalism has created the political, social and pedagogical landscape that accelerated the antidemocratic tendencies to create the conditions for a new authoritarianism in the United States. It has created a society ruled by fear, imposed massive hardships and gross inequities that benefit the rich through austerity policies, eroded the civic and formative culture necessary to produce critically informed citizens, and destroyed any sense of shared citizenship. At the same time, neoliberalism has accelerated a culture of consumption, sensationalism, shock and spectacularized violence that produces not only a widespread landscape of unchecked competition, commodification and vulgarity but also a society in which agency is militarized, infantilized and depoliticized.

New technologies that could advance social platforms have been used by groups, such as the Black Lives Matter movement, and when coupled with the development of critical online media to educate and advance a radically democratic agenda, have opened up new spaces of public pedagogy and resistance. At the same time, the landscape of the new technologies and mainstream social media operate within a powerful neoliberal ecosystem that exercises an inordinate influence in heightening narcissism, isolation, anxiety and loneliness. By individualizing all social problems along with elevating individual responsibility to the highest ideal, neoliberalism has dismantled the bridges between private and public life making it almost impossible to translate private issues into broader systemic considerations. Neoliberalism created the conditions for the transformation of a liberal democracy into a fascist state by creating the foundations for not only control of commanding institutions by a financial elite, but also by eliminating the civil, personal and political protections offered to individuals in a free society. If authoritarianism in its various forms aims at the destruction of the liberal democratic order, neoliberalism provides the conditions for that devastating transformation to happen by creating a society adrift in extreme violence, cruelty and disdain for democracy. Trump’s election as the president of the United States only confirms that the possibilities of authoritarianism are upon us and have given way to a more extreme and totalitarian form of late capitalism.

In your view, what role have educational institutions, such as universities, played in US society?

Ideally, educational institutions, such as higher education, should be understood as democratic public spheres — as spaces in which education enables students to develop a keen sense of economic justice, deepen a sense of moral and political agency, utilize critical analytical skills, and cultivate a civic literacy through which they learn to respect the rights and perspectives of others. In this instance, higher education should exhibit in its policies and practices a responsibility not only to search for the truth regardless of where it may lead, but also to educate students to make authority and power politically and morally accountable, while at the same time sustaining a democratic, formative public culture. Unfortunately, the ideal is at odds with the reality, especially since the 1960s when a wave of student struggles to democratize the university and make it more inclusive mobilized a systemic and coordinated attack on the university as an alleged center of radical and liberal thought. Conservatives began to focus on how to change the mission of the university so as to bring it in line with free-market principles while limiting the admission of minorities. Evidence of such a coordinated attack was obvious in claims by the Trilateral Commission’s report, The Crisis of Democracy, which complained of the excess of democracy and later in the Powell Memo, which claimed that advocates of the free market had to use their power and money to take back higher education from the student radicals and the excesses of democracy. Both reports in different ways made clear that the democratizing tendencies of the sixties had to be curtailed and that conservatives had to mount a defense of the business community by using their wealth and power to put an end to an excess of democracy, especially in those educational institutions which were responsible for «the indoctrination of the young,» which they viewed as a dire threat to capitalism. But the greatest threat to higher education came from the growing ascendency of neoliberalism in the late 1970s, and its assumption of power with the election of Ronald Reagan in the 1980s.

Under the regime of neoliberalism in the United States and in many other countries, many of the problems facing higher education can be linked to eviscerated funding models, the domination of these institutions by market mechanisms, the rise of for-profit colleges, the rise of charter schools, the intrusion of the national security state, and the slow demise of faculty self-governance, all of which make a mockery of the very meaning and mission of the university as a democratic public sphere. With the onslaught of neoliberal austerity measures, the mission of higher education was transformed from educating citizens to training students for the workforce. At the same time, the culture of business has replaced any vestige of democratic governance with faculty reduced to degrading labor practices and students viewed mainly as customers. Rather than enlarge the moral imagination and critical capacities of students, too many universities are now wedded to producing would-be hedge fund managers and depoliticized workers, and creating modes of education that promote a «technically trained docility.» Strapped for money and increasingly defined in the language of corporate culture, many universities are now driven principally by vocational, military and economic considerations while increasingly removing academic knowledge production from democratic values and projects. The ideal of higher education as a place to think, to promote dialogue and to learn how to hold power accountable is viewed as a threat to neoliberal modes of governance. At the same time, education is viewed by the apostles of market fundamentalism as a space for producing profits and educating a supine and fearful labor force that will exhibit the obedience demanded by the corporate order.

You have also written about the need and the possibilities of organizing forces of resistance and change during the Trump presidency. In particular, you have emphasized the importance of expanding the connections among diverse social movements. What are the groups that in your view could work together within the United States?

Single-issue movements have done a great deal to spread the principles of justice, equity and inclusion in the United States, but they often operate in ideological and political silos. The left and progressives as a whole need to unite to create a social movement united in its defense of radical democracy, a rejection of nondemocratic forms of governance, and rejection of the notion that capitalism and democracy are synonymous. There is a need to pull the different elements of the left together so as to both affirm single-issue movements and also recognize their limits when confronting the myriad dimensions of political, economic and social oppression, particularly given how the machinery and rationality of neoliberalism works to now govern all of social life.

It is crucial to recognize that given the hold of neoliberalism on American politics and the move of neofascism from the margins to the center of power, it is crucial for progressives and the left to unite in what John Bellamy Foster has described as their efforts «to create a powerful anti-capitalist movement from below, representing an altogether different solution, aimed at epoch-making structural change.»

What about the old idea of internationalism? Is it better to dedicate efforts to advancing in the national front or trying to build alliances between social movements and political forces from different countries in a longer process? Can both approaches be combined?

There is no outside in politics any longer. Power is global and its effects touch everyone irrespective of national boundaries and local struggles. The threats of nuclear war, environmental destruction, terrorism, the refugee crisis, militarism and the predatory appropriations of resources, profits and capital by the global ruling elite suggests that politics has to be waged on an international level in order to create resistance movements that can learn from and support each other. We need to create a new kind of politics that addresses the global reach of power and the growing potential for both mass destruction and mass global resistance. This does not suggest giving up on local and national politics. On the contrary, it means connecting the dots so that the links between local and state politics can be understood within the logic of wider global forces and the interests that shape them.

Another key idea that you are promoting is that progressive movements must also embrace those who are angry with existing political and economic systems, but who lack a critical frame of reference for understanding the conditions for their anger. Could you sketch out your understanding of a concept that is so important in your work, such as critical pedagogy?

Following theorists, such as Paulo Freire, Antonio Gramsci, C. Wright Mills, Raymond Williams and Cornelius Castoriadis, I have made central to my work the recognition that the crisis of democracy was not only about economic domination or outright repression but also involved the crisis of pedagogy and education. The late Pierre Bourdieu was right when he stated in his book Acts of Resistance that the left has too often «underestimated the symbolic and pedagogical dimensions of struggle and have not always forged appropriate weapons to fight on this front.» He also has stated that «left intellectuals must recognize that the most important forms of domination are not only economic but also intellectual and pedagogical, and lie on the side of belief and persuasion. It is important to recognize that intellectuals bear an enormous responsibility for challenging this form of domination.» These are important pedagogical interventions and imply that critical pedagogy in the broadest sense provides the conditions, ideals and practices necessary for assuming the responsibilities we have as citizens to expose human misery and to eliminate the conditions that produce it.

Pedagogy is about changing consciousness and developing discourses and modes of representations in which people can recognize themselves and their problems. It enables us to invest in a new understanding of both individual and collective struggle. Matters of responsibility, social action and political intervention do not simply develop out of social critique but also forms of self-reflection, critical analysis and communicative engagement. In short, any radical democratic project must incorporate the need for intellectuals and others to address critical pedagogy not only as a mode of educated hope and a crucial element of an insurrectional educational project, but also as a practice that addresses the possibility of interpretation as a form of intervention in the world.

It is crucial to recognize that any viable approach to a democratically inspired politics must embrace the challenge of enabling people to recognize and invest something of themselves in the language, representations, ideology, values and sensibilities used by the left and other progressives. This means taking up the task of making something meaningful in order to make it critical and transformative. Equally important is the need to give people the knowledge and skills to understand how private and everyday troubles connect to wider structures. As Stuart Hall has noted, «You can’t just rest with the underlying structural logic. And so you think about what is likely to awaken identification. There’s no politics without identification. People have to invest something of themselves, something that they recognize is of them or speaks to their condition, and without that moment of recognition … you won’t have a political movement without that moment of identification.»

Critical pedagogy can neither be reduced to a method nor is it nondirective in the manner of a spontaneous conversation with friends over coffee. As public intellectuals, authority must be reconfigured not as a way to stifle the curiosity and deaden the imagination, but as a platform that provides the conditions for students to learn the knowledge, skills, values and social relationships that enhance their capacities to assume authority over the forces that shape their lives both in and out of schools. I have argued for years that critical pedagogy must always be attentive to addressing the democratic potential of how experience, knowledge and power are shaped, both in the classroom and in wider public spheres and cultural apparatuses, extending from the social media and the internet to film culture and the critical and mainstream media. In this sense, critical pedagogy and education itself must become both central to politics and linked to the recovery of historical memory, to the abolition of existing inequities. At stake here is a «hopeful version of democracy where the outcome is a more just, equitable society that works toward the end of oppression and suffering of all.»

We can conclude the interview by looking at the future with some informed optimism. Can you explain the concept of militant hope?

Any confrontation with the current historical moment has to be contoured with a sense of hope and possibility so that intellectuals, artists, workers, educators and young people can imagine otherwise in order to act otherwise. While many countries have become more authoritarian and repressive, there are signs that neoliberalism in its various versions is currently being challenged, especially by young people, and that the social imagination is still alive. The pathologies of neoliberalism are becoming more and more obvious and the contradictions between rule by the few and the imperatives of a liberal democracy have become more jarring and visible. The widespread support for Bernie Sanders, especially among young people, is a hopeful sign as is the fact that many Americans favor progressive programs, such as government-guaranteed health care, social security and higher taxes for the rich.

For resistance not to disappear in the fog of cynicism, the urgency of the present moment demands recognizing that the cruel and harsh reality of a society that finds justice, morality and the truth repugnant has to be repeatedly challenged as an excuse for either a withdrawal from political life or a collapse of faith in the possibility of change. A militant hope should foster a sense of moral outrage and the need to organize with great ferocity. There are no victories without struggles. And while we may be entering a historical moment that has tipped over into an unapologetic authoritarianism, such moments are as hopeful as they are dangerous. The urgency of such moments can galvanize people into a new understanding of the meaning and value of collective political resistance.

What cannot be forgotten is that no society is without resistance, and hope can never be reduced to merely an abstraction. Hope has to be informed, concrete and actionable. Hope in the abstract is not enough. We need a form of militant hope and practice that engages with the forces of authoritarianism on the educational and political fronts so as to become a foundation for what might be called hope in action — that is, a new force of collective resistance and a vehicle for anger transformed into collective struggle, a principle for making despair unconvincing and struggle possible. Nothing will change unless people begin to take seriously the deeply rooted cultural and subjective underpinnings of oppression in the United States and what it might require to make such issues meaningful in both personal and collective ways, in order to make them critical and transformative. This is fundamentally a pedagogical as well as a political concern. As Charles Derber has expressed to me, knowing «how to express possibilities and convey them authentically and persuasively seems crucially important» if any viable notion of resistance is to take place.

http://www.truth-out.org/opinion/item/40188-the-menace-of-trump-and-the-new-authoritarianism-an-interview-with-henry-giroux

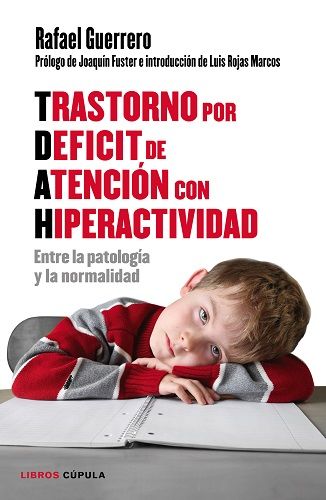

Llevo muchos años trabajando con niños y adolescentes diagnosticados de TDAH, y con sus familias y profesores. En el día a día veo la gran cantidad de sufrimiento que padecen en sus diferentes ámbitos (colegio, casa, con los amigos, a nivel emocional, etc), lo que me llevó a escribir un libro sobre el TDAH. En él se recogen los aspectos básicos de este trastorno con el fin de convertirse en un manual práctico para familiares, profesores y especialistas sin recursos para trabajar con esta población.

Llevo muchos años trabajando con niños y adolescentes diagnosticados de TDAH, y con sus familias y profesores. En el día a día veo la gran cantidad de sufrimiento que padecen en sus diferentes ámbitos (colegio, casa, con los amigos, a nivel emocional, etc), lo que me llevó a escribir un libro sobre el TDAH. En él se recogen los aspectos básicos de este trastorno con el fin de convertirse en un manual práctico para familiares, profesores y especialistas sin recursos para trabajar con esta población. Existen muchas herramientas y actividades para trabajar la atención con nuestros jóvenes con TDAH, solo es necesario dedicarle tiempo y echarle imaginación. Para proponer actividades a nuestros niños de la función ejecutiva que sea (atención, inhibición, planificación, memoria operativa, etc), lo más importante es conocer y entender el concepto. Una vez lo hemos estudiado, podemos proponer ejercicios como sopas de letras, encontrar las 7 diferencias entre dos imágenes, tachar las vocales que aparecen en una hoja llena de letras, buscar o imaginar elementos que sean de color rojo, que estén fríos o que se puedan encontrar en un colegio, etcétera.

Existen muchas herramientas y actividades para trabajar la atención con nuestros jóvenes con TDAH, solo es necesario dedicarle tiempo y echarle imaginación. Para proponer actividades a nuestros niños de la función ejecutiva que sea (atención, inhibición, planificación, memoria operativa, etc), lo más importante es conocer y entender el concepto. Una vez lo hemos estudiado, podemos proponer ejercicios como sopas de letras, encontrar las 7 diferencias entre dos imágenes, tachar las vocales que aparecen en una hoja llena de letras, buscar o imaginar elementos que sean de color rojo, que estén fríos o que se puedan encontrar en un colegio, etcétera.

-En tu intervención en la Mostra del Llibre Anarquista de Valencia te has referido a algunas mujeres invisibilizadas, como Dolores Iturbe (1902-1990). ¿Por qué fue importante?

-En tu intervención en la Mostra del Llibre Anarquista de Valencia te has referido a algunas mujeres invisibilizadas, como Dolores Iturbe (1902-1990). ¿Por qué fue importante?

Users Today : 160

Users Today : 160 Total Users : 35419964

Total Users : 35419964 Views Today : 227

Views Today : 227 Total views : 3354437

Total views : 3354437