Australia/Diciembre de 2016/Fuente: The Guardian

RESUMEN: La disminución de los resultados escolares se ha convertido en la prueba de Rorschach de la política australiana: la Coalición y el Trabajo ambos ven lo que quieren en cada conjunto de cifras decepcionantes. Hubo la noticia de que el desempeño de Australia en matemáticas y ciencias se ha reducido en los últimos 20 años y ha disminuido en comparación con los países comparables. Luego, el Programa de Evaluación Internacional de Estudiantes mostró una disminución a largo plazo en los resultados de los estudiantes del año 9 de Australia en matemáticas, ciencias y alfabetización en lectura. Las estadísticas publicadas por el ministro federal de Educación, Simon Birmingham, mostraron que el gasto educativo por estudiante había aumentado en un 49,6% entre 2003 y 2015, y un 11,9% entre 2011 y 2015, pero no había conseguido mejores resultados. Birmingham ha utilizado las cifras para reforzar su argumento de que un «alto nivel de financiación para nuestras escuelas es obviamente importante», pero el gobierno debe centrarse en la reforma escolar para ayudar mejor a los estudiantes. Pisa resultados no se ven bien, pero vamos a ver lo que podemos aprender antes de entrar en pánico.

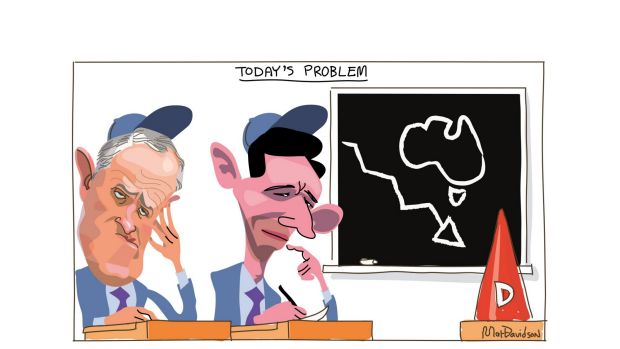

Declining school results have become the Rorschach test of Australian politics: the Coalition and Labor both see what they want in each set of disappointing figures.

There was the news that Australia’s performance in maths and science has flatlined for the past 20 years and slipped relative to comparable countries. Then the Programme for International Student Assessment showed a long-term decline in Australian year 9 students’ results in maths, science and reading literacy.

Statistics released by the federal education minister, Simon Birmingham, showed that per-student education spending had increased by 49.6% between 2003 and 2015, and by 11.9% between 2011 and 2015, but had failed to buy better results.

Birmingham has used the figures to bolster his argument that a “strong level of funding for our schools is obviously important”, but the government must focus on school reform to best help students.

The deputy opposition leader and shadow education minister, Tanya Plibersek, on the other hand, is persuaded that more funding is needed.

Birmingham cites OECD research that found higher expenditure on education did not guarantee better student performance. Among high-income economies, the amount spent on education is less important than how those resources are used.

Plibersek points out that less than 10% of needs-based funding had been distributed when students sat tests that turned in the flagging results.

The debate is heating up because the nation’s education ministers will meet on 16 December and discuss a new funding model for 2018 onwards. Demands for higher funding will be top of the states’ list.

But the federal government won’t make a formal proposal until 2017, when the Council of Australian Governments must approve it.

Plibersek says there is a false dichotomy between more funding and school reforms.

“This idea that money doesn’t matter, it’s all about the reforms – we agree it’s all about the reforms, but you need extra money to deliver them,” she tells Guardian Australia.

“If you want to do continuing professional development for teachers and have them spend a day with a highly qualified peer leader teacher in their classroom, you’ve got to pay for that teacher’s relief day.

“If you’re going to send them to do a coding workshop at university, an intensive day or week, you’ve got to pay for a relief teacher. All of this costs money.”

The experience of Glenroy Central primary school in Victoria illustrates Plibersek’s argument.

Its principal, Jo Money, says the school spent its $321,152 in equity funding in 2016 on maths education, including online assessment tools and teacher training.

The school got an injection of equity funding because of its high proportion of students from low socio-economic backgrounds and high proportion students for whom English is not their or their parents’ first language.

“To actually provide the time for teachers to observe each other is very expensive,” Money says. “We invested in technology so kids can get online results immediately and it all costs money we just don’t have.”

She says Glenroy Central didn’t have “the sort of community that we could ask to pay” for those improvements. The school had to buy computers for kids who otherwise wouldn’t have access to them, and it teaches a number of refugees who need everything provided, including uniforms.

The school got a boost in its Naplan maths results and Money speaks glowingly of the “snowballing confidence” the schools’ teachers and students experienced.

Labor does not want to be pigeon-holed as the party that just wants more money. Plibersek rattles off reforms that Labor has agreed to in principle: better entry standards for teaching courses, greater principals’ autonomy, continuing education for teachers and evidence-based policies.

The Coalition released its quality school reforms in May, including measures to reward more experienced teachers, improve teacher quality and test phonics skills in year one students.

Plibersek says the reforms Australian schools needed are already contained in the previous Labor government’s national education reform agreement, but blames the former education minister Christopher Pyne for stripping conditions out to allow schools to chart their own course to improvement.

She says Birmingham can talk the talk of boosting school standards, but since that decision, Australia has been spinning its wheels and wasting time that should have been spent improving teacher quality.

Birmingham has said he welcomes Labor to the school reform debate, which he suggests the Coalition is leading while Labor “muddied the waters” with “lies” about cuts to funding – which is still growing.

Which brings us back to the funding debate. At the 2013 election the Liberal leader, Tony Abbott, promised no cuts to education.

After the Coalition won the election, Pyne announced the government intended to renegotiate Labor’s needs-based funding agreements, arguing the Coalition had only agreed the total amount of funding would be the same, not that every school would get the same.

The Coalition backed down, but then in the 2014 budget the government cut $29bn from schools’ projected funding growth over 10 years, arguing Labor had never properly funded it.

The Coalition stuck to the same funding levels for the first four years of Labor’s needs-based funding deals, but did not guarantee the fifth and sixth years of funding despite some states signing six-year deals.

This drew the battle lines for the 2016 election. Labor promised a further $37.3bn over 10 years for the “full Gonski” needs-based funding.

The Coalition promised less for schools than Labor, but that federal funding would still grow from $16bn in 2016 to around $20.1bn in 2020. Funding would also be allocated on need, but the model for how that is distributed is still up in the air.

Birmingham tells Guardian Australia he “wouldn’t pre-empt discussions on the specific details of a new model”, which won’t be finalised until the first half of 2017.

“Everyone agrees that funding needs to be distributed according to need and we all want to help boost student outcomes,” he says.

“I’m looking forward to working with my state and territory colleagues to iron out the problems with the current distribution of funding and to implement reforms in our schools that are proven to lift student performance.”

“Ironing out” problems means revisiting the agreements Labor struck to implement needs-based funding, then parcel it up differently, while still adhering to the principle that the most disadvantaged students get more funding.

Birmingham has taken up the argument that Labor’s plan is a “corruption” of Gonski principles, as it was labelled by one of its architects, Ken Boston. The minister argues Labor struck 27 “inconsistent” deals with states, territories and their public, Catholic and independent school sectors.

Birmingham gave an example that under the current arrangements “a disadvantaged student in one state receives up to $1,500 less federal funding than a student in another state in the exact same circumstance”.

“Contrary to some claims, these gaps actually get worse with time, where in 2019 the difference blows out to more than $2,100,” he said.

Birmingham says Labor’s school funding deal “fails their own fairness test, where a child’s postcode or the state they live in is determining the different federal funding they receive, or where special deals from years ago are entrenched for decades to come”.

Plibersek says Birmingham’s talk of 27 different agreements and “corruption” of Gonski principles is “an attempt to distract” from the cuts in the 2014 budget, which she says were a broken promise because states and voters expected the same funding from both sides.

She says the education minister is “pitting state against state, saying some states are doing better than others, school against school and system against system”.

The states are also pushing back against plans to renegotiate deals that could leave them worse off.

Victoria calculates that not implementing the deals will cost its education system almost $1bn a year every year from 2018, although the federal government criticises the state for not confirming it will fund its part of the deal.

The Victorian education minister, James Merlino, has said the federal government “has no formal policy” to replace existing funding agreements, and the slated funding increase was inadequate and only amounted to an increase to indexation.

As Guardian Australia reported on Saturday, Merlino wants states to have more say in the new funding model and has rejected federal conditions that, he says, interfere with operational issues that are state responsibilities.

The New South Wales premier, Mike Baird, and its education minister, Adrian Piccoli, have called for the federal government to honour its six-year deal with the state and will do so again next week.

In October Baird said there was “absolutely no doubt” that needs-based funding benefited students.

“The extra support students are receiving is showing real results,” he says. “Funding now follows students and their needs, and principals have the flexibility to make local decisions based on the specific needs of their students.”

Piccoli says NSW is on board with the federal reform agenda, which mirrors its own efforts, and would push for higher entry standards for teachers.

Western Australia supports renegotiation of funding agreements, which Plibersek attributes to the fact that the state signed a “dud deal” with Pyne rather than signing up under the previous Labor government.

In late November the Grattan Institute lent support to the idea that the Julia Gillard-era deals were not implementing needs-based funding as quickly as possible.

It found current trajectories for growth of funding entrenched disparities between schools because all schools receive annual funding increases between 3% and 4.7%

Restructuring the funding agreements could see the neediest schools reach the funding standard sooner by cutting taxpayer support for “overfunded” schools.

In a blitz of interviews to defend higher levels of school funding, Plibersek was repeatedly drawn into debates about whether some private schools were overfunded as a result of Labor’s promise no school would go backwards.

She called the argument “a distraction” because, even if the Grattan Institute reforms were implemented, cutting “overfunded” private schools’ allocation would raise just $200m compared with a $4bn cut in years five and six of Gonski funding.

Plibersek has previously said there was “no compelling case” to cut the funding. Now she delivers a crisper formulation: she doesn’t want to give the idea any oxygen.

Asked whether Labor will keep its pledge for $37.3bn over 10 years, Plibersek says it will stick with a “very significant financial commitment”, but will “accept there might be changes [the government may] make along the way”. It leaves wiggle room to accept cuts to “overfunded” schools, if they come.

Plibersek accuses Birmingham of not having developed a concrete proposal for how schools should be funded from 2018.

“It’s very easy to say you don’t like this system or what we inherited, but he hasn’t put any positive suggestions yet,” she says. “There’s the suggestion some private schools are overfunded, without saying whether he intends to take their money away.”

For Plibersek, the education minister has to answer and answer quickly: what comes next?

She says there were different agreements because each state and territory came from a different starting position, and there is a public, Catholic and independent system in each.

“The idea that you’d have one agreement meeting all this is nonsense – it’s always been nonsense,” Plibersek said.

A “cookie cutter” funding model is not possible overnight, but by 2020 states and territories will hit 95% of the school resourcing standard, she says.

“Share the better model with schools if you think there is one,” Plibersek challenges Birmingham.

State and territory education ministers don’t expect a concrete proposal on 16 December. But the lines have been drawn between a federal government determined to push for much better performance from a system with modest increases in funding, and an opposition keen to argue you get what you pay for and significant improvements will require significant investment.

Fuente: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/dec/11/this-costs-money-why-school-funding-is-the-rorschach-test-of-australian-politics

Users Today : 5

Users Today : 5 Total Users : 35460497

Total Users : 35460497 Views Today : 14

Views Today : 14 Total views : 3419372

Total views : 3419372