Fuente TES / 9 mde junio de 2016

Reflecting on a great week in Australia, I detect a new education debate opening up to replace the false dichotomy between knowledge and skills. Across three continents I hear more thought leaders arguing that we should now focus on individualised education rather than standardised schooling.

I spent almost a whole day at the University of Melbourne’s Graduate School of Education. This is the home of Professor John Hattie, and I was the guest of the distinguished dean, Professor Field Rickards. Both were fresh from collaborating on a new series for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation called Revolution School. This is set in a school that has moved from the bottom 10 per cent to the top 10 per cent. It is authentic but hopeful. It shows off the university’s clinical approach to education, with evidence of impact on individual learners rather than a class average.

Professor Field impressed on me that producing impact for every learner demonstrates the complexity and challenge of teaching. It shows the need for professionalism, accepting that every teacher has different strengths and weaknesses and that collaboration is crucial in tackling different effectiveness.

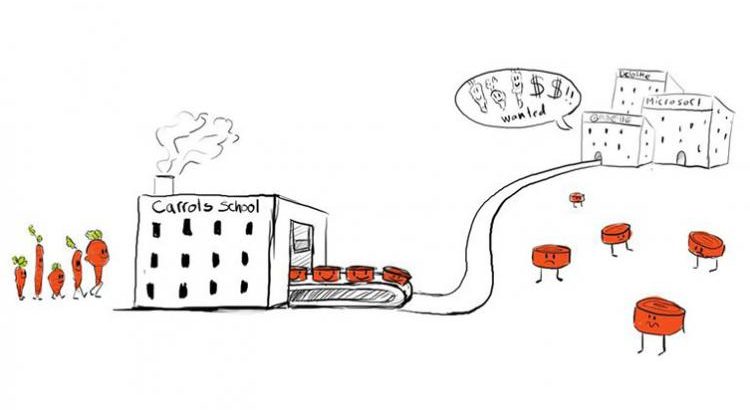

This approach, based on evidence of individual impact, is a long way from the «factory schooling» promoted in TES by Jonathan Simons (article free to subscribers).

His advocacy of a system that raises standards for the average is logical but flawed, especially in the light of an insightful book I read last week on my travels: The End of Average by Todd Rose. It made me much more hopeful that the approaches of Dame Alison Peacock or the Dalton system, also featured in last week’s TES, are more likely to be enduring.

Todd Rose is the director of the Mind, Brain, and Education programme at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, where he also leads the Laboratory for the Science of the Individual. His book starts by demonstrating that designing for the average person can fail because no one is completely average – we are all unique. Testing, ranking and grading is common to factories, and is convenient for sorting people at a cost to individual talent.

The labour market of the post-industrial world is changing. Technology and globalisation will remove the need for many lower- and medium-skilled jobs and makes the waste of talent in schooling for the average unsustainable. Without factories to utilise the work of those that are failed by factory schooling, how are those people supported? What is more, the attempts to rank people based on qualification, or things like IQ tests, are being abandoned by some employers.

Google, Deloitte and Microsoft have all dropped single-score employee evaluation systems. The correlation between performance in work and grade point average just wasn’t there. Employers are now looking for a more complete picture of candidates, which the data can now start to offer.

The consequences for education are significant if employers stop sifting on the basis of grades or going to the «right» university. The opportunity is for education to focus entirely on helping individuals to develop relative to their own performance rather than their peers. In his report The Problem Solvers, Charles Leadbeater argues that this requires education being more dynamic. This is a «combination of cognitive and non-cognitive skills, hard and soft, explicit and tacit, academic knowledge and entrepreneurial ambition». This in turn will require assessment to «go beyond testing routine recall of facts to test higher-order thinking, problem-solving and creativity; and will deliver qualitative descriptions and expert judgments of how well a student performs, as well as test results and grades».

I also met another Harvard professor while I was in Melbourne. Professor Richard Elmore argued for similar change but warned that there were plenty of vested interests that would try to shout it down. A move from industrial schooling of grading and sorting people is very threatening to some. But I see no alternative as the world changes around us. The challenge is to take measured steps in the right direction of individualised education while we wait for policymakers to catch up.

Fuente: globalpartnership.org / 9 de junio de 2016

Since 2000 significant gains have been achieved in access to primary education globally, however, the quality of learning remains a major challenge.

According to UNESCO, an estimated 250 million children either don’t make it to grade 4 or reach grade 4 without basic skills in reading, writing and math.

Factors such as poverty and extreme inequality put children at greater risk of not learning the basics. Living in rural areas or in remote parts of a country also reinforces disadvantages.

Schools in remote areas frequently lack trained teachers, and instructional materials are inadequate and often in short supply. These factors make it difficult for children and youth from marginalized groups to develop strong foundational skills in reading, writing and numeracy.

Fuente Times Higher Education / 9 de junio de 2016

The average academic is working unpaid for the equivalent of two days every week, says a new study on the growth of “unreasonable, unsafe and excessive” workloads.

Academic staff work an average of 50.9 hours per week, according to the latest University and College Union workload survey, Workload is an Education Issue. The study is based on responses from about 12,100 university staff, most of whom work full time.

This means that academics work on average 13.4 hours – almost two days – more than the normal 37.5 hour working week, and work in excess of the 48 hour maximum recommended by the European Working Time Directive.

Senior academic staff work even longer hours on average, says the report, which was published at the UCU’s congress, held in Liverpool from 1 to 3 June.

UCU congress: UCU reps ‘need protected characteristic’ to attend equality event

UCU congress: Prevent: v-cs ‘under pressure’ to stay silent

Professors work 56.1 hours on average and principal research fellows 55.7 hours, although there is also a culture of long hours, often unpaid, among many early career academics, says the report.

One in six academics aged 25 or under work 100 or more hours each week when part-time appointments are adjusted to their full-time equivalent, it adds.

The vast majority of staff (83 per cent) also say that the pace or intensity of workload has increased over the past three years, with only 14 per cent reporting that their workload is not heavier.

Adam Price, professor in the University of Aberdeen’s Institute of Biological and Environmental Sciences, told congress that the UCU’s findings were borne out by studies of official timesheet data at his university compiled by the local branch.

“I work 55 hours a week and began to think ‘this is not normal’, but it is normal,” said Professor Price.

Other delegates said that the introduction of new technology has increased their workload as they are now expected to put together packages of online materials for students in addition to their existing duties.

Ron Mendel, senior lecturer in sociology at the University of Northampton, said the extra work generated by this type of technologically enhanced teaching has a “deleterious effect on workload, professional well-being and [staff’s] professional lives”.

According to the workload survey, some 13 per cent – about one in eight respondents – feel they work “unreasonable, unsafe and excessive hours”, while 29 per cent say their workload is “unmanageable” all or most of the time. Two-thirds (66 per cent) say it is unmanageable at least half the time.

On the activities that now consume much more of their time than three years ago, teaching and research staff most often cite departmental administration (51 per cent), while student-related administration is mentioned by 45 per cent and departmental meetings by 31 per cent.

Some 28 per cent of academics say their marking load has increased significantly, while 26 per cent say they carry out much more pastoral care for students than in 2013.

The long hours culture is far less prevalent among professional and support staff, although the average 42.4 hour working week reported indicates these employees also undertake significant amounts of unpaid overtime, the report suggests.

Fuente FECODE / 9 de junio de 2016

Docentes y comunidad educativa han desarrollado varias marchas para denunciar lo que está ocurriendo y exigir soluciones inmediatas. La administración ha hecho caso omiso a sus necesidades.

La tercera Encuesta de Opinión Sindical, contratada por la Escuela Nacional Sindical, evidenció el reconocimiento del gremio con el trabajo de Fecode y su gestión en defensa de los derechos del magisterio, así como el acompañamiento al proceso de paz y las precarias condiciones del derecho a la sindicalización en un estado de derecho como Colombia.

Los sindicalistas del país consideran que los tres temas en los que el gobierno debe centrar su atención son: a) generación de trabajo decente, b) disminución del desempleo y c) las libertades sindicales. La encuesta destacó el trabajo de fecode con un 86.5% por su liderazgo social, político y de restitución de derechos.

Este es un documento visibiliza la opinión de los sindicatos y trabajadores, su quehacer para incidir en la agenda nacional sobre temas estructurales como el trabajo decente, el proceso de paz y la violación al derecho a la sindicalización.

“Nos encontramos que instituciones relacionadas con el mundo laboral, como el caso de los jueces laborales, la Corte Constitucional y la Contraloría General de la Nación, entre otras, tuvieron un porcentaje de desconfianza bastante alto, lo que evidencia que la desconfianza en este tipo de instituciones aumentó. Sin embargo, permanece la percepción que tienen los líderes y lideresas sindicales sobre el maltrato que reciben de instituciones como la ANDI, Fedesarrollo, etc., y el poco reconocimiento que estas mismas les dan a ellos como representantes de organizaciones de los trabajadores”, precisó Carmen Lucía Tangarife, responsable de la temática Trabajo Decente y Mundo Laboral en la ENS.

Un dato tremendamente relevante es que tan solo el 1% de los líderes encuestados tiene entre 25 y 35 años. De ahí la importancia de insistir en la vinculación de jóvenes a las organizaciones, de motivar el derecho a la sindicalización y la reivindicación laboral, que garantice el relevo generacional. La encuesta es una muestra contundente de la importancia del liderazgo sindical y su incidencia real en el diseño y aplicación de políticas públicas y sociales en el país.

Fuente: Internacional de la educación / 9 de mayo de 2016

El mensaje de hoy en Riga, Letonia, se ha centrado en los cimientos de una educación con un enfoque inspirado en los derechos humanos, que incluya valores universales como la comprensión y la tolerancia, y que entienda las diferencias culturales como una oportunidad en lugar de como una amenaza.

Fuente: Internacional de la educación / 9 de Junio de 2016

Preparar a los estudiantes de hoy en día para su realidad multicultural va más allá de la enseñanza de los derechos humanos como lección independiente de una clase; al contrario, requiere la creación de un entorno donde todos comprendan, valoren y protejan los derechos humanos.