Fuente TES / 9 mde junio de 2016

Reflecting on a great week in Australia, I detect a new education debate opening up to replace the false dichotomy between knowledge and skills. Across three continents I hear more thought leaders arguing that we should now focus on individualised education rather than standardised schooling.

I spent almost a whole day at the University of Melbourne’s Graduate School of Education. This is the home of Professor John Hattie, and I was the guest of the distinguished dean, Professor Field Rickards. Both were fresh from collaborating on a new series for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation called Revolution School. This is set in a school that has moved from the bottom 10 per cent to the top 10 per cent. It is authentic but hopeful. It shows off the university’s clinical approach to education, with evidence of impact on individual learners rather than a class average.

Professor Field impressed on me that producing impact for every learner demonstrates the complexity and challenge of teaching. It shows the need for professionalism, accepting that every teacher has different strengths and weaknesses and that collaboration is crucial in tackling different effectiveness.

A long way from ‘factory schooling

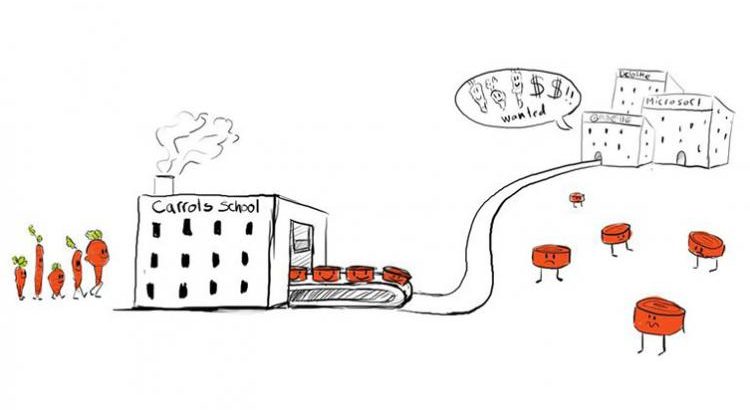

This approach, based on evidence of individual impact, is a long way from the «factory schooling» promoted in TES by Jonathan Simons (article free to subscribers).

His advocacy of a system that raises standards for the average is logical but flawed, especially in the light of an insightful book I read last week on my travels: The End of Average by Todd Rose. It made me much more hopeful that the approaches of Dame Alison Peacock or the Dalton system, also featured in last week’s TES, are more likely to be enduring.

Todd Rose is the director of the Mind, Brain, and Education programme at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, where he also leads the Laboratory for the Science of the Individual. His book starts by demonstrating that designing for the average person can fail because no one is completely average – we are all unique. Testing, ranking and grading is common to factories, and is convenient for sorting people at a cost to individual talent.

The labour market of the post-industrial world is changing. Technology and globalisation will remove the need for many lower- and medium-skilled jobs and makes the waste of talent in schooling for the average unsustainable. Without factories to utilise the work of those that are failed by factory schooling, how are those people supported? What is more, the attempts to rank people based on qualification, or things like IQ tests, are being abandoned by some employers.

Google, Deloitte and Microsoft have all dropped single-score employee evaluation systems. The correlation between performance in work and grade point average just wasn’t there. Employers are now looking for a more complete picture of candidates, which the data can now start to offer.

Individual focus

The consequences for education are significant if employers stop sifting on the basis of grades or going to the «right» university. The opportunity is for education to focus entirely on helping individuals to develop relative to their own performance rather than their peers. In his report The Problem Solvers, Charles Leadbeater argues that this requires education being more dynamic. This is a «combination of cognitive and non-cognitive skills, hard and soft, explicit and tacit, academic knowledge and entrepreneurial ambition». This in turn will require assessment to «go beyond testing routine recall of facts to test higher-order thinking, problem-solving and creativity; and will deliver qualitative descriptions and expert judgments of how well a student performs, as well as test results and grades».

I also met another Harvard professor while I was in Melbourne. Professor Richard Elmore argued for similar change but warned that there were plenty of vested interests that would try to shout it down. A move from industrial schooling of grading and sorting people is very threatening to some. But I see no alternative as the world changes around us. The challenge is to take measured steps in the right direction of individualised education while we wait for policymakers to catch up.

Users Today : 4

Users Today : 4 Total Users : 35460135

Total Users : 35460135 Views Today : 6

Views Today : 6 Total views : 3418789

Total views : 3418789