Africa/ Mozambique/ 24.06.2019/ Fuente: www.hrw.org.

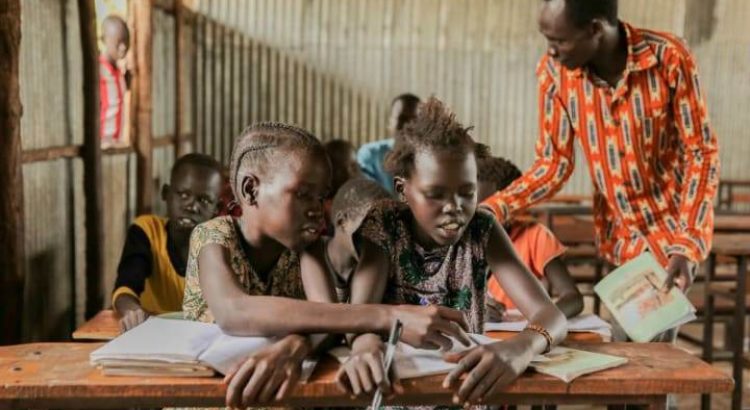

Children with albinism face insecurity and significant obstacles to accessing quality education in the Tete province of Mozambique, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

The report, «From Cradle to Grave”: Discrimination and Barriers to Education for Persons with Albinism in Tete Province, Mozambique is in the form of a special web feature with video and photos. Human Rights Watch found children living with albinism in the central Mozambican province of Tete to be widely discriminated against, stigmatized, and often rejected at school, in the community, and, at times, by their own families. They struggle to overcome barriers such as insecurity, bullying, and lack of reasonable adjustments in the classroom, which violates their right to education. Although the Mozambique government has taken important steps to better protect the rights of children with albinism, it needs to do more to ensure equal access to education.

“Children with albinism have the same right as everyone else to a quality education with reasonable support to facilitate their learning,” said Shantha Rau Barriga, disability rights director at Human Rights Watch. “Yet many children with albinism in Tete are relegated to the margins of the education system, and of society as a whole.”

Human Rights Watch interviewed over 60 people between July 2018 and May 2019 in Tete province and in Mozambique’s capital, Maputo. Interviewees included 42 children and young adults with albinism and their relatives; albinism and disability rights activists; community leaders; teachers and school principals; and representatives of international organizations. Human Rights Watch also met with government officials in May and reviewed relevant national and international legislation and policies.

Albinism is a relatively rare condition caused by a lack of melanin or pigmentation in the skin, hair, and eyes. People with albinism usually have a paler, whiter appearance than their relatives. While albinism affects one out of about every 17,000 to 20,000 people in Europe and North America, it is more widespread in Sub-Saharan Africa, with reports indicating that it affects one in 1,000 people in southern Africa, where Mozambique is located.

Although not everyone with albinism has a disability, the melanin deficit can result in low vision and an increased vulnerability to the sun’s ultra-violet rays. People with albinism living in Sub-Saharan Africa are about 1,000 times more likely to develop skin cancer than the general population.

In 2012, Mozambique ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which guarantees the right to inclusive, quality education. This entails ensuring that children with and without disabilities learn together in mainstream classes in an inclusive environment, with reasonable accommodations.

Fear of Violence

In late 2014, there was a surge of attacks on people with albinism in Mozambique, including kidnapping and trafficking. At the peak in 2015, the UN independent expert on the enjoyment of human rights by persons with albinism received reports from nongovernmental groups of over 100 attacks that year alone. A belief in witchcraft is one of the root causes of attacks, the independent expert said, with assailants believing that body parts from people with albinism can produce wealth and good luck.

Although the reports of attacks and abductions have receded, the families of children with albinism still live in fear, some keeping their children out of school. The most recent report of an attack was the abduction of an 11-year-old girl in May in Murrupula district in Nampula Province. She was later found dead with her limbs cut off.

Joao, a 19-year-old from the Angónia district, told Human Rights Watch that around 2015, he stopped going to school for fear of being kidnapped during the long walk from home. He said people would sometimes follow him. Others would call him “money” and “business,” referring to his valuable body parts. Joao’s family went to the police after assailants allegedly tried to recruit his friend to help abduct him.

“My dream was to become a teacher,” he said. “It’s good work. I still have the dream but I can’t go to school.” Today, Joao works in the fields with his father, planting beans and corn. The work is hard and painful, because the sun hurts his skin.

The Mozambique government should increase efforts to dispel deadly myths about albinism, including through workshops and at outdoor cinemas in the local language, particularly in rural and isolated communities – such as those across Tete – that may not have access to television and radio due to a lack of electricity.

Barriers at School

Children with albinism face numerous obstacles at school, including bullying by students and sometimes teachers, little to no reasonable accommodation for their low vision, and requirements to participate in physical education classes outside without proper protection from the sun.

Human Rights Watch found that in schools in Tete province, students with albinism who also have low vision lack access to appropriate learning materials, such as large-print textbooks, extra time for exams, or seating arrangements next to the blackboard.

Fatima, 20, said she dropped out of school in Grade 5 after insensitive teachers bullied her.

When she would try to sit in the front of the class to see the blackboard better, one teacher would yell, “You albino, you stay where you are,” she said. Her father complained to the school, but it only made things worse. “When the teacher would say those things to me, it allowed the students to do the same. There were no consequences for any of them,” Fatima said.

The government should ensure that all teachers in the public education system are sensitive to the needs of children with albinism and trained to adequately provide for their needs. Schools should have resources to meet their needs, including textbooks and exams with larger fonts, and assistive devices to read the blackboard, Human Rights Watch said.

Government Response

In recent years, the Mozambique government has taken important steps to protect people with albinism, including adopting a comprehensive Action Plan in 2015 to deal with violence against people with albinism. The plan includes measures to promote education and awareness of albinism among families and communities. However, human rights advocates in Maputo said that although they participated in drafting the plan, the government has left them out of implementation, reducing its effectiveness. They also remain concerned that the plan lacks a specific budget, which seriously impairs effective implementation.

At the Global Disability Summit in 2018 in Britain, Mozambique pledged to create inclusive education policies and plans, including carrying out a national strategy for inclusive education. The most recent draft strategy for inclusive education was silent on children with albinism, but the Education Ministry has promised to revise it to include language on albinism.

As a priority, Mozambique’s government should also carry out the recommendations outlined in the Regional Action Plan on Albinism in Africa, the first continental strategy to address violations against people with albinism. The plan, endorsed by the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights in 2017, contains a series of immediate to long-term measures focused on protection, prevention, accountability, and non-discrimination.

“By taking steps to make sure that children with albinism can get a meaningful education while continuing to investigate and prosecute those responsible for attacks, the Mozambique government has an opportunity to further show its commitment to ensuring safety, inclusion, and dignity for people with albinism,” Barriga said.

Source of the notice: https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/06/13/mozambique-education-barriers-children-albinism

Users Today : 6

Users Today : 6 Total Users : 35460667

Total Users : 35460667 Views Today : 11

Views Today : 11 Total views : 3419756

Total views : 3419756