By: Martin La Monica.

The coronavirus outbreak may be the biggest disruption to international student flows in history.

There are more than 100,000 students stuck in China who had intended to study in Australia this year. As each day passes, it becomes more unlikely they will arrive in time for the start of the academic year.

Of course international affairs are bound to sometimes interfere with the more than 5.3 million students studying outside their home country, all over the world.

After the September 11 attacks in 2001, the United States closed its borders temporarily and tightened student visa restrictions, particularly for students from the Middle East. Thousands were forced to choose different study destinations in the following years.

In 2018, Saudi Arabia’s government instructed all its citizens studying in Canada to return home, in protest at the Canadian foreign minister’s call to release women’s rights activists held in Saudi jails.

A significant proportion of the 12,000 or so Saudi students in Canada left to continue their studies elsewhere, before the Saudi government quietly softened its stance.

So we have seen calamities before, but never on this scale. There are a few reasons for this.

Why this is worse than before

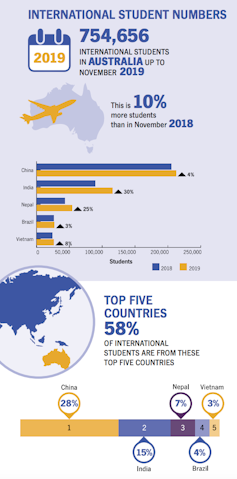

The current temporary migration of students from China to Australia represents one of the largest education flows the world has ever seen. Federal education department data show there were more than 212,000 Chinese international students in Australia by the end of 2019.

This accounts for 28% of Australia’s total international student population. Globally, there are only two study routes that involve larger numbers of students. The world’s largest student flow is from China to the United States and the second largest is from India to the US.

It’s also difficult to imagine a worse time for this epidemic to happen for students heading to the southern hemisphere than January to February, at the end of our long summer break.

Many Chinese students had returned home for the summer and others were preparing to start their studies at the end of February.

By comparison, the SARS epidemic in 2003 didn’t significantly dent international student enrolments in Australia because it peaked around April-May 2003, well after students had started the academic year.

Read more: We need to make sure the international student boom is sustainable

Ending in July that year, the SARS outbreak infected fewer than half the number of people than have already contracted coronavirus. Even during the SARS outbreak Australia didn’t implement bans on those travelling from affected countries.

What will the impact be?

This crisis hits hard for many Chinese students, an integral component of our campus communities. It not only causes disruptions to their study, accommodation, part-time employment and life plans, but also their mental well-being.

A humane, supportive and respectful response from the university communities is vital at this stage.

Australia has never experienced such a sudden drop in student numbers.

The reduced enrolments will have profound impacts on class sizes and the teaching workforce, particularly at masters level in universities with the highest proportions of students from China. Around 46% of Chinese students are studying a postgraduate masters by coursework. If classes are too small, universities will have to cancel them.

And the effects don’t end there. Tourism, accommodation providers, restaurants and retailers who cater to international students will be hit hard too.

Chinese students contributed A$12 billion to the Australian economy in 2019, so whatever happens from this point, the financial impact will be significant. The cost of the drop in enrolments in semester one may well amount to several billion dollars.

The newly-formed Global Reputation Taskforce by Australia’s Council for International Education has commissioned some rapid response research to promote more informed discussion about the implications and impacts of the crisis.

Read more: What attracts Chinese students to Aussie universities?

If the epidemic is contained quickly, some of the 100,000 students stuck in China will be able to start their studies in semester one, and the rest could delay until mid-year. But there might still be longer-term effects.

Australia has a world-class higher education system and the world is closely watching how we manage this crisis as it unfolds.

Prospective students in China will be particularly focused on Australia’s response as they weigh future study options.

The world is watching

Such a fast-moving crisis presents a range of challenges for those in universities, colleges (such as English language schools) and schools who are trying to communicate with thousands of worried students who can’t enter the country.

Australian universities are scrambling to consider a wide range of responses. These include:

- delivering courses online

- providing intensive courses and summer or winter courses

- arrangements around semester commencement

- fee refund and deferral

- provision of clear and updated information

- support structures for starting and continuing Chinese students, including extended academic and welfare support, counselling, special helplines, and coronavirus-specific information guidelines

- support with visa issues, accommodation and employment arrangements.

A coordinated approach involving different stakeholders who are providing different supports for Chinese students is an urgent priority. This includes education providers, government, city councils, international student associations, student groups and professional organisations.

Source of the review: https://theconversation.com/the-coronavirus-outbreak-is-the-biggest-crisis-ever-to-hit-international-education-131138

FT企画・インターナショナルスクール20190617201451744_Datare-750x410.jpg)

Users Today : 10

Users Today : 10 Total Users : 35460219

Total Users : 35460219 Views Today : 13

Views Today : 13 Total views : 3418908

Total views : 3418908