Authors: This report has been written by Rebecca Gordon, Lauren Marston, Pauline Rose and Asma Zubairi in the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre, Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge.

Reseña: Escrito por la Universidad de Cambridge, el estudio proporciona nuevos análisis e información sobre las barreras a la educación de las niñas en los países de la Commonwealth y las medidas necesarias para desmantelarlas. Como hogar de más de la mitad de los niños sin escolarizar del mundo, los países de la Commonwealth tienen un papel importante que desempeñar en la realización de los objetivos mundiales en educación y hay mucho que podemos hacer para aprender y apoyarnos mutuamente. El informe sugiere que los gobiernos de todo el mundo necesitan destinar más fondos a los primeros años de educación, especialmente para las niñas en áreas rurales remotas. También destaca la necesidad de enfoques específicos para ayudar a las niñas a superar los muchos desafíos que enfrentan al llegar a la pubertad. Un proyecto reciente en Kenia implementó «conversaciones comunitarias», cuyo objetivo era abordar las normas dañinas que conducen al matrimonio precoz. Se encontró que estas conversaciones disminuyen los niveles de abandono escolar de las niñas y aumentan la asistencia. En Jamaica, la Fundación del Centro de Mujeres ayuda a reintegrar a las niñas a la escuela secundaria después de dar a luz, mediante una combinación de matrícula académica, provisión de guarderías y otros servicios de salud. Las participantes tienen más probabilidades de completar su educación y menos probabilidades de tener un segundo embarazo. El informe proporciona muchos otros ejemplos de lo que funciona para proporcionar a más niñas una educación de calidad. Lo alentamos a leer este importante informe, que nos lleva un paso más cerca de comprender mejor cómo podemos lograr un mundo donde todos los niños tengan acceso a una educación de calidad. La tarea para los gobiernos y los educadores ahora es aprender lecciones e implementar los mejores modelos a escala. Para eso, necesitamos un compromiso político visible de los países de todo el mundo y una inversión sostenida de recursos. Debemos mantener el impulso para garantizar que las niñas más pobres del mundo completen 12 años de educación de calidad. Estamos profundamente comprometidos con este tema y trabajaremos junto con los colegas del Gabinete y con la Plataforma para la Educación de las Niñas para promover acciones concretas.

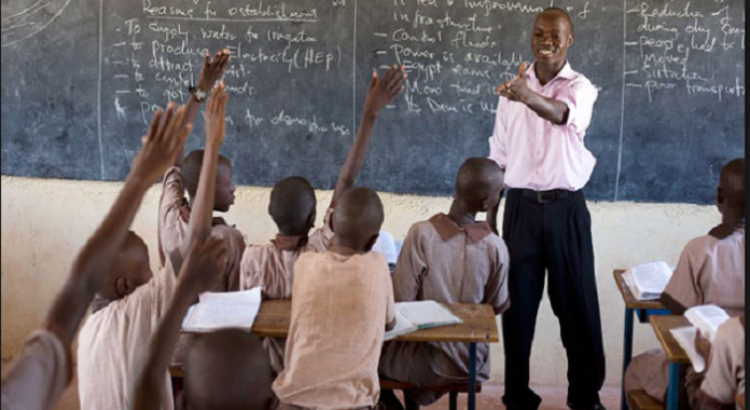

Written by the University of Cambridge, the study provides fresh analysis and insights into the barriers to girls’ education in Commonwealth countries, and the measures that are needed to dismantle them. As home to over half of the world’s out of school children, Commonwealth countries have a major role to play in realizing the global goals on education and there is much we can do to learn from and support one another.

The report suggests that governments across the world need to target more funding to the early years of education, especially for girls in remote rural areas. It also highlights the need for targeted approaches to help girls overcome the many challenges they face as they reach puberty.

A recent project in Kenya implemented ‘community conversations’, which aimed to tackle harmful norms that lead to early marriage. These conversations were found to decrease levels of girls’ dropout from school and increase attendance.

In Jamaica, the Women’s Centre Foundation helps to reintegrate girls into secondary school after they have given birth, through a combination of academic tuition, nursery provision, and other health services. Participants are more likely to complete their education and less likely to have a second pregnancy. The report provides many other examples of what works to provide more girls with a quality education.

We encourage you to read this important report, which takes us a step closer to understanding better how we can achieve a world where all children have access to quality education. The task for governments and educationalists now is to learn lessons and implement the best models at scale. For that, we need visible political commitment from countries across the world and sustained investment of resources.

We must keep up the momentum to ensure that the world’s poorest girls complete 12 years of quality education. We are deeply committed to this issue and will work together with Cabinet colleagues and with the Platform for Girls’ Education to promote concrete action.

Descargar: https://www.educ.cam.ac.uk/centres/real/downloads/Platform%20for%20Girls/REAL%2012%20Years%20of%20Quality%20Education%20for%20All%20Girls%20A4_Summary.pdf

Fuente: http://www.ungei.org/index_6561.html

India is committed to education reform based on hard evidence and is eager to contribute to the work of the Global Alliance to Monitor Learning (

India is committed to education reform based on hard evidence and is eager to contribute to the work of the Global Alliance to Monitor Learning (

Users Today : 28

Users Today : 28 Total Users : 35459494

Total Users : 35459494 Views Today : 36

Views Today : 36 Total views : 3417794

Total views : 3417794