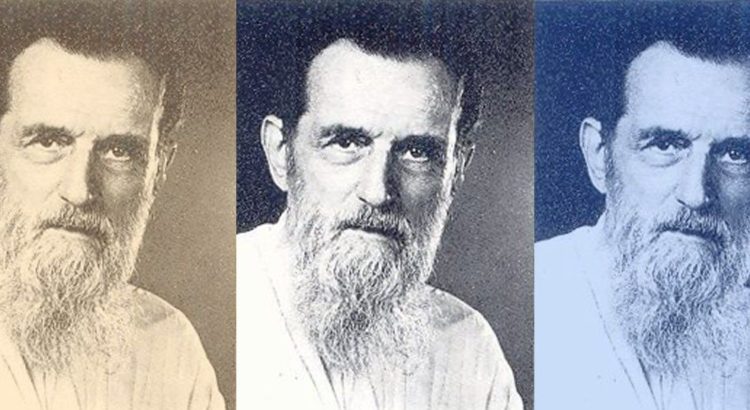

The year was 1945. Father Camille Bulcke, or Baba Bulcke as he liked to be called, was adamant that he would only write his PhD thesis at Allahabad University, if the Vice Chancellor, Dr Amarnath Jha, changed the rule that all submissions be made in English, and allowed Bucke to compete his research in Hindi.

The thesis, submitted in 1949, was later published as the book Ramkatha Ki Utpatti aur Vikaas (The Genesis and Development of Ramkatha).

This September, Bulcke would have been 107 years old.

Linguistic pride

Bulcke left Belgium in 1935 and arrived in India at the peak of the Indian National Movement, just when the Government of India Act had been passed. He was 26, and had been a Jesuit for only five years when he fell in love with the country, its people and language.

While the National Movement pushed for an end to British colonial rule, speaking English was growing increasingly important. People were using English to serve the colonial masters, and both foreign missionaries and Indians preferred English at the cost of indigenous languages.

At this time, it was Bulcke who decided to master the language of the people, Hindi, and waged one of the earliest and and longest battles to restore linguistic pride to it.

Bulcke considered translations critical for the development of a language, and in 1955, he published a technical English-Hindi Glossary, which ran into two editions. The success of the glossary inspired him to take on more projects: in 1968, he wrote the Angrezi Hindi ShabdKosh (English -Hindi dictionary).

This particular dictionary became extremely popular in government offices in Bihar and Jharkhand, where Hindi served as the official language. In fact there was scarcely a middle class home in Bihar those days, where the Bulcke dictionary could not be found prominently displayed on a shelf.

At inter-college competitions in Jharkhand/Bihar, it is still possible to find the Bulcke Angrezi Hindi Shabdkosh distributed as a prize. Bulcke was frequently annoyed with people who mixed English words in Hindi sentences – the present-day affliction of speaking Hinglish would have been an abomination in his linguistic worldview.

Bulcke was always eager to translate important works from different languages to Hindi – he believed this would spread their reach to wider audiences. His books can still be found at the library at Manresa House in Ranchi, which has been the main center of activities for the Jesuits of Chhotanagpur.

Among Bulcke’s last projects was the translation of the autobiography of the Theosophist, Annie Besant, but, unfortunately, it was never completed. His last work, written in collaboration with Dr Dineshwar Prasad, was theRamcharitmanas Kaumudi.

Viewed with reverence

When he first arrived to India, the hills and climes of Darjeeling did not suit Bulcke. So he made his way to Gumla, Jharkhand, where he would teach mathematics for the next five years.

In his biography of Bulcke, long-time collaborator Dr Dineshwar Prasad mentions how Bulcke wasted no time getting to his Hindi lessons at the St. Ignatius school in Gumla, where he could be found sitting on the last bench with the students to develop fluency in the language. Soon, he mastered Brajbhasha as well as Awadhi, adding to the five European languages and Sanskrit, which he already spoke.

Once Bulcke received his PhD at the Allahabad University, he returned to Ranchi in 1950 as the head of the Sanskrit department at St. Xavier’s College. During this time, he published several deeply researched theological and philosophical works on Indology, taught Hindi and Sanskrit for several years. The road to his college is still known as the Camille Bulcke Path.

Bulcke spent his life researching Tulsidas, the Ramcharitmanas and the similarities in the lives of Ram and Christ. His seminal works include Ek Isai ki Astha: Ramkatha aur Hindi (A Christian’s Faith: Ramkatha and Hindi), Ramkatha aur Tulsidas and Theism of Nyaya Vaisheshika.

Those who knew Bulcke remember that he frequently took offence when people referred to him as a «foreign scholar of Hindi». He would remind people that he had acquired Indian citizenship in 1951.

In 1974, he was honoured with the Padma Bhushan for services rendered to the Hindi language, and was also declared a member of the Royal Academy in Belgium. He was affiliated with several organisations and committees in the Nehruvian era, which oversaw the development and popularity of Hindi.

Post his tea time, Bulcke was often spotted cycling to rural areas near the college, meeting and socialising with locals. Prasad’s biography of Bulcke also mentions his deep love for the people of Jharkhand and the village life of the Adivasis. He often entertained fellow Jesuits with the recitations of famous poems. One of his favourite poems to recite was:

We who were born in villages

Far from the towns and changing faces

We have a special birthright

Which cannot be sold by anyone

And a special mysterious pleasure

Which cannot be uttered in words

— Author’s translation from Hindi

Those of us who spent our childhood in Ranchi remember the reverence Baba Bulcke inspired across religious communities.

In strict Vaishnava homes where the Ramcharitmanas was read as a devotional text, this Christian Padre on the cycle was a reveredkathavachak (narrator): he extolled virtues of the Sundarkand. He loved Tulsi’s Ramcharitmanas and its lyrical poetry in Awadhi, written in a devotional style which appealed to his Jesuit senses. He spoke about about the multiple ways in which the story of Ramayana had been imagined across time and cultures. In his book on Ramkatha, Bulcke talks about Tibetan, Nepali, Odiya, Bengali, Kashmiri, Buddhist, Jain and multiple South Indian and South East Asian versions of the Ramayana story. Much before AK Ramanujan’s Three Hundred Ramayanas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translation, it was Bulcke who made the strongest case for multiple narratives of the timeless epic.

If yogis like Paramhans Yogananda took Hindu philosophy to the West and studied its coexistence with Christianity, it was Bulcke who brought Christianity with him, studying its compatibity with Indian traditions. When he was not talking about the Ramkatha, Bulcke preached at local churches from time to time. For him, there was no conflict between his Christian faith, his love for India, and Hindu religious discourses and philosophical traditions.

Towards the end of his life Bulcke suffered from severe hearing problems (despite the use of a hearing aid) and gangrene. He finally died on August 17, 1982, and was buried at one of Delhi’s oldest British cemeteries, the Nicholson Cemetery near Kashmiri Gate.

Baba Bulcke’s Ranchi is no longer the peaceful world that he had helped create and nurture. The communal and violent sloganeering against Muslims and Christians that has become the forte of Hindutva bhakts goes against the grain of Bulcke’s life and devotion to the Ramkatha. Remembering, reading and understanding Bulcke could be the much-needed antidote to the communal hatred.

The writer is Senior Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at Monash University, Australia, and Visiting Fellow, Centre for the Study of Developing Societies in Delhi.

Tomado de: http://scroll.in/bulletins/23/india-uk-and-the-us-agree-that-this-one-factor-is-the-biggest-contributor-to-a-fulfilled-life

Users Today : 21

Users Today : 21 Total Users : 35460152

Total Users : 35460152 Views Today : 35

Views Today : 35 Total views : 3418818

Total views : 3418818