Por Amy Goodman & Juan González,

Reseña: A medida que las huelgas de docentes en Denver y Los Ángeles se unen a una ola de acciones laborales recientes que llaman la atención sobre la difícil situación del sistema de escuelas públicas de EE. UU. Observamos de nuevo uno de los escándalos de escuelas públicas más grandes en la historia de los Estados Unidos. Las escuelas públicas de Atlanta, Georgia, se lanzaron al caos en 2015 cuando 11 ex educadores fueron condenados en 2015 por cargos de extorsión y otros cargos por supuestamente facilitar una operación de trampa masiva en exámenes estandarizados. Los fiscales dijeron que los maestros se vieron obligados a modificar las respuestas incorrectas y que incluso se les permitió a los estudiantes corregir sus respuestas durante los exámenes. El caso ha alimentado las críticas sobre la dependencia del sistema educativo en las pruebas estandarizadas y suscitó llamamientos de racismo. Treinta y cuatro de los 35 educadores acusados en el escándalo eran afroamericanos. Hablamos con Shani Robinson, uno de los 11 maestros condenados, que ha escrito un nuevo libro sobre el escándalo de la trampa con la periodista Anna Simonton. Se titula Ninguno de los anteriores: la historia no contada del escándalo de engaño de las escuelas públicas de Atlanta, la codicia corporativa y la criminalización de los educadores .

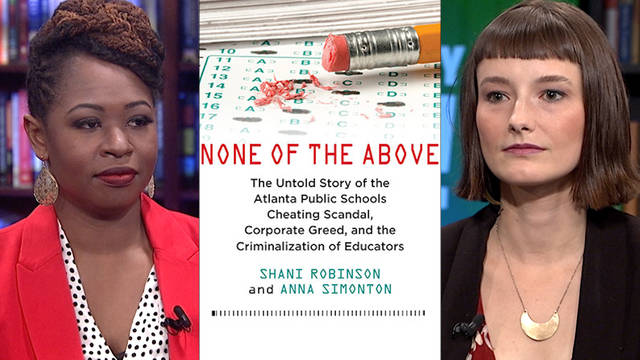

As teacher strikes in Denver and Los Angeles join a wave of recent labor actions bringing attention to the plight of the American public school system, we take a fresh look at one of the largest public school scandals in U.S. history. Public schools in Atlanta, Georgia, were thrown into chaos in 2015 when 11 former educators were convicted in 2015 of racketeering and other charges for allegedly facilitating a massive cheating operation on standardized tests. Prosecutors said the teachers were forced to modify incorrect answers and students were even allowed to fix their responses during exams. The case has fueled criticism of the education system’s reliance on standardized testing, and elicited calls of racism. Thirty-four of the 35 educators indicted in the scandal were African-American. We speak with Shani Robinson, one of the 11 convicted teachers, who has written a new book on the cheating scandal with journalist Anna Simonton. It’s titled None of the Above: The Untold Story of the Atlanta Public Schools Cheating Scandal, Corporate Greed, and the Criminalization of Educators.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, we turn now to the fight for public education, as the teachers’ strike in Denver heads into its third day. District and union negotiators worked late into the night Tuesday on a potential agreement, including a base salary of $45,800 a year for educators. That would be a $2,500 boost from their expected pay for 2019-’20 school year. But the Denver Classroom Teachers Association is still demanding the district rely less on bonuses and instead focus on financial security for educators.

Denver’s teachers are striking for the first time in a quarter of a century. Their walkout comes just weeks after an historic 6-day teachers’ strike in Los Angeles ended with victory for educators demanding smaller class sizes and higher wages. The actions are the latest in a wave of teachers’ strikes that began last year in Republican-controlled states like West Virginia, Oklahoma and Arizona. The strikes have brought renewed attention to the plight of the American public school system, which teachers say is under attack.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re now joined by a former educator who says the teachers’ strikes can help shed light on one of the largest public school scandals in U.S. history. Shani Robinson is a former first-grade teacher in Atlanta, Georgia, who was convicted for what prosecutors said was her role in the massive cheating scandal that roiled the school district and drew national attention in 2015. Robinson was one of 11 former educators convicted of racketeering and other charges. Prosecutors say teachers were forced to modify incorrect answers and students were even allowed to fix their responses during exams.

This is Judge Jerry Baxter, speaking after the verdict was handed down. He ordered most of the educators immediately behind bars, an unusual move for first-time offenders.

JUDGE JERRY BAXTER: I made myself plain, from early on. And they have made this decision, and they have — they have — they’ve not fared well. And I don’t like to send anybody to jail. It’s not one of the things I get a kick out of. But they have made their bed, and they’re going to have to lie in it. And it starts today.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Two of the convicted former educators turned themselves in, in October, to begin their prison sentences. Nine were sentenced to jail but rejected sentencing agreements in order to appeal. Twenty-one defendants avoided trial with plea deals. The case has fueled criticism of the education system’s reliance on standardized testing, and elicited calls of racism, because 34 of the 35 educators indicted in the scandal were African-American.

AMY GOODMAN: Shani Robinson has written a new book on the cheating scandal, with journalist Anna Simonton. It’s called None of the Above: The Untold Story of the Atlanta Public Schools Cheating Scandal, Corporate Greed, and the Criminalization of Educators. In the book, Shani Robinson writes, “[T]he dominant narrative that developed about the scandal rarely acknowledged the bigger picture: federal policies that encouraged school systems to reward and punish educators based on student test scores; a growing movement, driven by corporate interests, to privatize education by demonizing public schools; and land speculation — correlated to new charter schools springing up — that was gentrifying Black and brown neighborhoods across the country.”

We’re joined now in our New York studio by Shani Robinson, who’s still awaiting an appeal in the case. Also with us, Anna Simonton, independent journalist, editor for Scalawag magazine, graduate of the Atlanta Public Schools, co-author, with Shani Robinson, of None of the Above.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now!

SHANI ROBINSON: Thank you for having us.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you are appealing these charges. I mean, you basically were charged under laws to get the mafia.

SHANI ROBINSON: Correct. I was facing 25 years in prison. I was charged with racketeering and false statements and writings.

AMY GOODMAN: So, explain — lay out the story. Go back to 2013. Tell us what happened.

SHANI ROBINSON: So, the APS cheating scandal was a period —

AMY GOODMAN: Atlanta Public Schools.

SHANI ROBINSON: The Atlanta Public Schools cheating scandal was a period of time in which educators were accused of changing their students’ answers from wrong to right on standardized tests. And so, I was actually a teacher for three years in Atlanta Public Schools. And my second year teaching, I was a first-grade teacher, and that later becomes the year in question.

ANNA SIMONTON: 2009, yeah.

SHANI ROBINSON: In 2009. And as a first-grade teacher, my test scores actually did not count toward the district targets, which were benchmarks imposed by the APSschool board and administration, or the federal standards, which was adequate yearly progress.

And so, in October of 2010, I get a phone call from a GBI agent, Georgia Bureau of Investigation, and he asked me to come in to, strangely, a mall parking lot, is where I met him. And he tells me that there’s been an erasure analysis done for the entire state of Georgia. Twenty percent of the schools over the entire state of Georgia were flagged for high erasures.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain erasures.

SHANI ROBINSON: So, the erasure analysis was basically looking at how many times a student — right, a student’s went from wrong to right.

AMY GOODMAN: Erases their answer.

SHANI ROBINSON: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: And makes it right.

SHANI ROBINSON: And goes from wrong to right, right. After a certain amount, it’s like statistically improbable, outside of human intervention. And so, the agent told me that in my class specifically, there were high levels of wrong-to-right erasures. And he asked me: Can I explain this? And I say, “No, I can’t explain this.” And then he asked me: Well, did any administrators or the principal ever place any pressure on me to cheat on my students’ test booklets? And I said, “No.”

And then he pulls out a prewritten, voluntary statement form, which was basically saying you don’t have any knowledge about cheating, you didn’t cheat. And he asked me to sign this form. Now, the thing about this form is that later it’s used against many educators who signed the form. They were charged with false statements and writings, which is a felony. And so, teachers were really put between a rock and a hard place, because here you have a GBI agent — and, mind you, there were no attorneys present. I didn’t have an attorney present. And when they went into the schools, teachers were pulled from their classrooms and interrogated, so there really were no attorneys present. And so you have this GBI agent asking you to sign a form, and if you don’t sign the form, you didn’t really want to become a target, you know, but if you did sign the form, you could potentially become a felon.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Now, let me ask you, the entire investigation, it was touched off, wasn’t it, by a series in The Atlanta Constitution that began questioning the percentage of erasures that they were uncovering in their investigation? What impact did that series have on the general Atlanta community? And obviously it touched off the law enforcement officials.

SHANI ROBINSON: Right. And there were — at that time, I believe there were about — it was over about — there were about five schools, across five districts. And so, that prompted the governor to do a statewide investigation. And so — and just to even go into as far as like the widespread cheating is concerned, over 40 states in this country have had evidence of cheating allegations. Fourteen of those states, it was considered to be widespread. In Washington, D.C., there were 103 schools that were flagged for high — suspiciously high erasures or test scores. So, this was actually something that was happening across the country. So, what we can’t figure out is why teachers in Atlanta were slapped with felony charges. Some of my co-defendants were facing prison sentences of up to 40 years.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Anna Simonton, I’d like to ask you in terms of the broader picture. Now, this happens — these indictments come down in the middle of the Obama administration. President Obama and Arne Duncan, his education secretary, were very much into performance-based measures of teachers and standardized testing as a way — as a key way to measure whether a student is doing a good job. Could you talk about the pressures that were put on educators, and not only on the educators, but their supervisors, their principals and their superintendents, during this period of time?

ANNA SIMONTON: Yeah. This was a long-running trend beginning in the early 1990s, when high-stakes testing began to be utilized in school districts, like Houston’s. But it was really codified in federal law in 2001 with No Child Left Behind, which was signed by George W. Bush. But Obama really continued the policies of No Child Left Behind in practice, if not in name.

And one interesting piece to this story is how our governor at the time, Sonny Perdue, used the same 2009 test scores to apply for a $400 million Race to the Top grant. So, Race to the Top was a grant under the Obama administration for states that could show that they were doing some of these education reforms that the federal government was pushing — so, expanding charters, increasing high-stakes testing — that they could get federal funding. And so, at the same time that Sonny Perdue sends in GBIagents to the schools of Atlanta because he suspects that the 2009 CRCTtest scores are fraudulent, he’s using those same test scores to say, “Hey, look, our test scores are going up.” And they did win that $400 million federal grant.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Anna, why did you get involved with Shani in writing this book, None of the Above? You, too, went to Atlanta Public Schools. Why was this so interesting to you?

ANNA SIMONTON: I did. I had to take these tests, and they were a drain on the actual education that I feel like students should be getting in the classroom. They’re, in my view, a waste of time.

But more important is that my middle school counselor was actually convicted in this case. I, like many people, watched the convictions handed down, not having really followed the trial. It was an 8-month trial, the longest criminal trial — excuse me — in Georgia history. And so it was hard for people to kind of understand what was happening as it dragged out. But when the convictions were handed down, it was like heartbreaking to see someone who I remembered being this like beacon in my own childhood, along with these other teachers. And so, when Shani reached out to me, it was just a wonderful opportunity to do something about it and try to tell another side of the story.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to break and then come back to this discussion. Our guests are Anna Simonton, independent reporter, editor for Scalawag, also joining us is Shani Robinson. She was the youngest of the teachers convicted in the Atlanta cheating scandal. She is appealing her conviction. Two teachers just recently went to jail. This is Democracy Now! Their book is called None of the Above. We’ll talk more about it in a minute.

Fuente: https://truthout.org/video/corporate-greed-and-criminalizing-teachers-in-atlanta-school-cheating-scandal/

Users Today : 4

Users Today : 4 Total Users : 35459470

Total Users : 35459470 Views Today : 4

Views Today : 4 Total views : 3417762

Total views : 3417762