Informe GEM Report

A lot of the discussion, and rightly so, has been about the effect of school closures on students. Education, as they know it, stopped from one day to the next. But what about teachers? Just as students are new to distance learning, most teachers are also novices in being distance coaches. We look at the pressure placed on teachers, the absence of training on distance learning in the past for teachers, the sorts of skills needed, the new tools and ways of coping teachers are now being plied with – but, first of all, the need to support the teaching workforce during these times of uncertainty.

Teachers need support during this crisis

Teachers have gone from fearing for their health, as schools continued during the pandemic, to fearing for their jobs in some contexts. Many in the United States fear that their pay rises are in jeopardy, for instance. It was also recently reported that Kenya teachers on the payroll of Bridge Academies, which currently works in around 2000 schools in five countries, will only be paid 10% of their salaries for two months of compulsory leave as a result of the pandemic – a period that risks being extended. Given that they don’t receive much more than USD$100 per month, this leaves them with little to survive on.

Teachers need training on distance learning

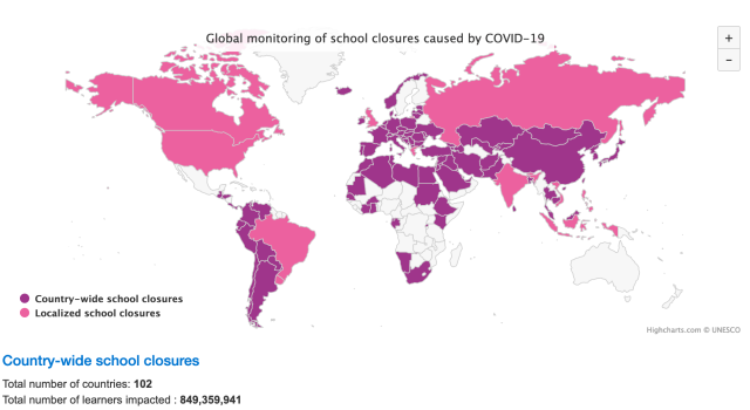

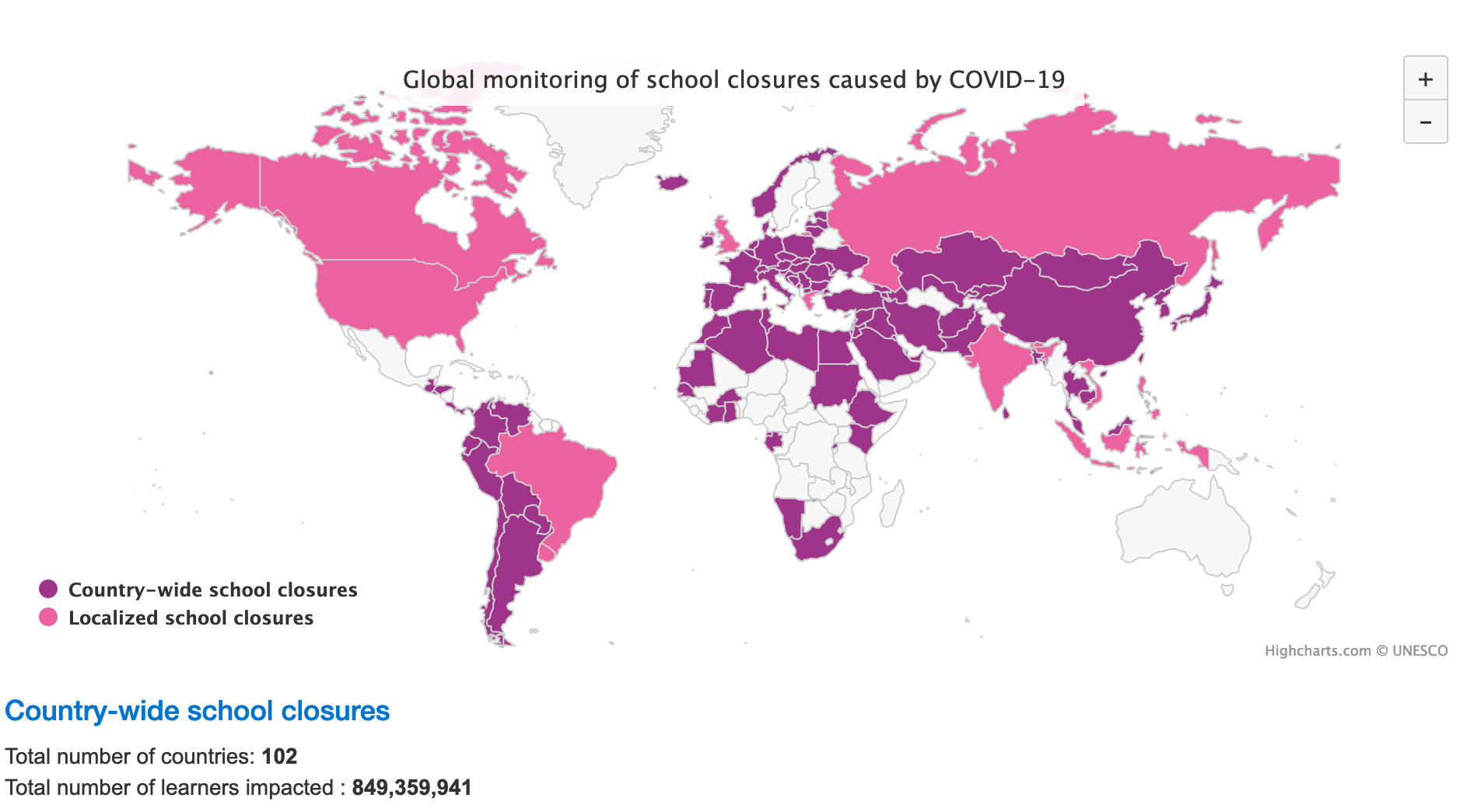

With schools now closed in 185 countries, teachers are having to suddenly take a crash course in how to keep lessons going online, adapting what and how they were teaching before to an entirely different teaching situation.

With schools now closed in 185 countries, teachers are having to suddenly take a crash course in how to keep lessons going online, adapting what and how they were teaching before to an entirely different teaching situation.

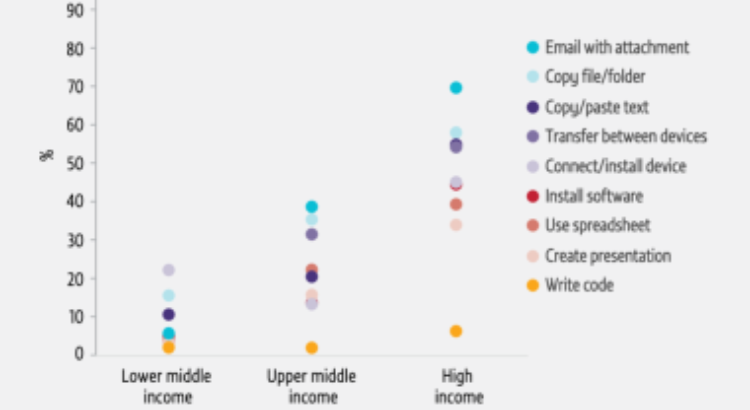

But many teachers are not up to scratch on ICT skills. The figure from the 2019 GEM Report, while not teacher specific, which gives some idea of how education systems may be overestimating the chances of distance learning working successfully. Only 40% of adults in upper middle-income countries are able to send an email with an attachment – a seemingly vital skill for any teacher hoping to send around classwork.

The infrastructure for distance learning is also not always available in schools. The OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) shows that only 53% of teachers let their students frequently or always use ICT for projects or classwork. But the share of teachers using ICT in countries such as Finland, Israel and Romania had more than doubled over the five years preceding the survey.

In the United Arab Emirates, 42,000 teachers took part last week in a ‘Be an online tutor in 24 hours’ course provided by the Ministry of Education. A ‘Design an online course in 24 hours’ is being rolled out next week. This training was fast-forwarded in the face of the virus but comes supported by an Arabic and English e-learning platform, Madrasa, launched in 2018.

But such preparation is an exception. Just as parents are complaining that sending them a link and assuming their child will learn is not fair, countries handing out laptops or other devices assuming teachers will get with the times might be in for a surprise. In Singapore, which plans to give a digital device to all secondary school students by 2024, the devices were initially given to 8 schools as a test. “We learned many things from this pilot project” said Minister for Education Ong Ye Kung in March this year. “Number one, teachers cannot teach the traditional way using e-learning. They need new pedagogies – e-pedagogies.”

In Kenya, the evaluation of a programme introducing ICT into schools in four schools and funded by VVOB also found that teachers faced challenges once the pilot had finished: not only lack of electricity, infrastructure and connectivity, but also a continuous need for training. It concluded that teachers need constant reiterations of learning about emerging technologies and how to use them. A fancy solution, like those many are getting now in the face of the pandemic, will therefore not suffice.

Some interesting initiatives are emerging to assess just how big the ed-tech gap is in schools and among teachers. In South Africa, for instance, an app, the e-ready ICT maturity assessment tool, supported by the Department for Education, asks schools to answer questions that can be completed in offline mode. The app then accords one of five e-readiness levels to that school, including teacher ICT readiness and teacher development and support. An external evaluation is also conducted and the overall results are then used by the Department to see where to focus its effort.

What skills do teachers need for distance learning?

Many skills have been touted as necessary to make the shift. It might seem that all that is required is ICT skills, including assisting students who face access issues. But the real difference that can be made from a shift to distance learning is how a teacher then uses e-pedagogies to keep students engaged.

One education consulting firm, Education Elements, believes that flexibility is the key skill required. The controlled structure of a school is lost outside of school walls. Teachers are not going to know exactly who is learning what and how quickly. They need to stick to simple lesson plans and maintain frequent and clear communications with students. Newsletters, video messages, virtual classrooms, emails, phone calls, text messages, and posts on social media could all be useful to remain in touch.

What solutions are out there to help?

Aside from countries taking up the task themselves, a host of organizations have also stepped into the fray to help teachers with this crash-course. Google, for instance, has just announced a new resource for teachers called ‘Teach from home’, a hub of information , tips and training and a $10 million Distance Learning Fund. The first $1-million grant from this Fund is going to the Khan Academy to provide remote learning opportunities including resources in more than 15 languages, aiming to reach over 18 million learners a month from communities around the globe.

The culture for distance learning is not yet here (and we are witnessing the growing pains of being late to that party) but it may well be by the time this pandemic has past. As we look to design solutions for the long-term on this issue, teachers must be consulted to learn from their experiences. They will be vital partners in policy development for distance learning in the future.

- Read the guiding principles to the Pandemic by Education International

- Read the call to support teachers by the Teacher Task Force

Fuente: https://gemreportunesco.wordpress.com/2020/04/01/covid-19-wheres-the-discussion-on-distance-learning-training-for-teachers/

By

By

Por GEM REPORT

Por GEM REPORT

Users Today : 33

Users Today : 33 Total Users : 35460296

Total Users : 35460296 Views Today : 44

Views Today : 44 Total views : 3419012

Total views : 3419012