South Africa /News 24

South Africa’s deficient education system is the single greatest obstacle to socio-economic advancement, replicating rather than reversing patterns of unemployment, poverty, and inequality, and effectively denying the majority of young people the chance of a middle-class life.

This emerges from a report, ‘Education the single greatest obstacle to socio-economic advancement in South Africa’, published by the Centre for Risk Analysis (CRA) at the Institute of Race Relations (IRR).

Set against data showing high rates of urbanisation – reflecting a common yearning for better-paying jobs, and a shot at middle-class life in a city – as well as a marked shift in the structure of the economy towards high-skills sectors, the research at once underscores the vital importance of education, and the devastating impacts of its most chronic deficiencies.

A new approach to schooling is urgently needed, according to author of the report, CRA director Frans Cronje, and should focus on achieving much higher levels of parental involvement and control, rather than bureaucratic control.

The report acknowledges that much, in fact, has changed for the better in recent decades.

Positive outcomes include the fact that pre-school enrolment has soared by 270.4% since 2000, setting a much better basis for future school throughput, that the proportion of people aged 20 or older with no schooling has fallen from 13% in 1995 to 4.8% in 2016, and that the proportion of matric candidates receiving a bachelor’s pass has increased from 20.1% in 2008 to 28.7% last year.

The good news doesn’t end there.

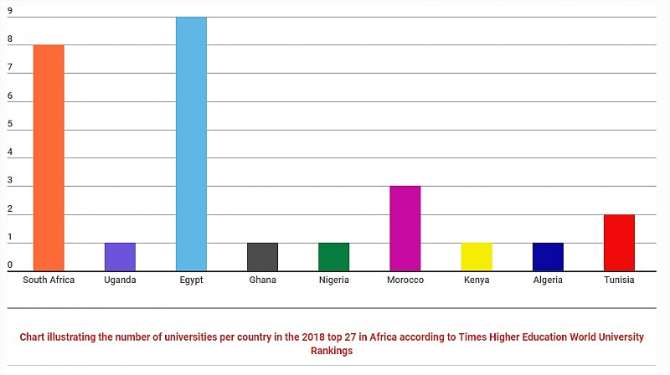

Higher education participation rates (the proportion of 20–24 year olds enrolled in higher education) have risen from 15.4% in 2002 to 18.6% in 2015, with university enrolment numbers climbing 289.5% since 1985 and more than 100% since 1995.

The ratio of white to black university graduates was 3.7:1 in 1991, narrowing to 0.3:1 in 2015, and the proportion of people aged 20 and older with a degree has increased from 2.9% in 1995 to 4.9% in 2016.

But, in just short of a dozen bullet points, the grimmer side of South African education is laid bare:

- Just under half of children who enrol in grade one will make it to Grade 12;

- Roughly 20% of Grade 9, 10, and 11 pupils are repeaters, suggesting that they have been poorly prepared in the early grades of the school system;

- Just 28% of people aged 20 or older have completed high school;

- Just 3.1% of Black people over the age of 20 have a university degree compared to 13.9% and 18.3% for Indian and White people;

- Just 6.9% of matric candidates will pass Maths with a grade of 70% to 100% – a smaller proportion than in 2008 (bearing in mind that, once the near 50% pre-matric drop-out rate is factored in, this means that around three out of 100 children will pass Maths in matric with such a grade);

- The ratio of Maths Literacy (a B-grade Maths option) to Maths candidates in matric has changed from 0.9:1 in 2008 to 1.5:1 in 2016;

- In the poorest quintile of schools, less than one out of 100 matric candidates will receive a distinction in maths;

- In the richest quintile, that figure is just 9.7%;

- Just one in three schools has a library and one in five a science laboratory;

- The Black higher education participation rate is just 15.6%, while that for Indian and White people (aged 20–24) is 49.3% and 52.8%; and

- The unemployment rate for tertiary qualified professionals has increased from 7.7% in 2008 to 13,2% today.

Author Frans Cronje notes: «The data makes it clear that education or the lack thereof is the primary indicator that determines the living standards trajectory of a young South African.

«In the second quarter of 2017, the unemployment rate for a tertiary qualified person was 13.2% – less than half the national average of 27.7%. Likewise, the labour market absorption rate for tertiary qualified professionals was 75.6% in 2017 as opposed to just 43.3% for the country as a whole.»

Three factors were particularly worrying.

«The first is the poor quality of Maths education. A good Maths pass in matric is in all probability the most important marker in determining whether a young person will enter the middle classes. While Maths education is poor across the board, the quality is worse in the poorest quintile of schools, leaving no doubt that school education is replicating trends of poverty and inequality in our society.»

The second is the low rate of tertiary education participation among black people.

Cronje warns that «it is futile to think that significant middle-class expansion, let alone demographic transformation, will take place as long as the higher education participation rate remains at around 15% for Black people».

The third is the «still very high» school drop-out rate.

«Just over half of [the] children will complete high school at all. In an economy that is evolving in favour of high-skilled tertiary industries and in which political pressure and policy are being used to drive up the cost of unskilled labour, this means that the majority of those children are unlikely to ever find gainful employment,» Cronje writes.

Putting these three concerns together, «you cannot escape the conclusion that the education system represents the single greatest obstacle to socio-economic advancement in South Africa».

«It replicates patterns of unemployment, poverty, and inequality and denies the majority of young people the chance of a middle-class life,» Cronje concludes. «The implications speak for themselves.»

– Morris is head of media at the Institute of Race Relations (IRR).

Fuente: https://www.news24.com/Analysis/south-africas-deficient-education-system-20180507

.jpg)

Users Today : 66

Users Today : 66 Total Users : 35460197

Total Users : 35460197 Views Today : 92

Views Today : 92 Total views : 3418875

Total views : 3418875