William Ayers

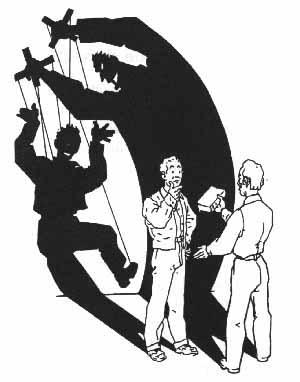

En La Caverna, José Saramago ofrece un gris pero, por extraño que parezca, esperanzador retrato de la alienación y del mundo moderno: A Cipriano Algor, un alfarero de 64 años, quien vive en su alfarería con su hija Marta, con pocos meses de embarazo, y con su yerno Marcial Gacho, quien es guardia del monolítico Centro ubicado en el corazón de la ciudad, le informan que no se venderán más piezas de alfarería y que sus contratos serían cancelados. La razón que le dan es que la cerámica se quiebra y el plástico es más práctico. Cipriano siente que es un hombre fuera de época, un anacronismo. Esta mala noticia llega al mismo tiempo que Marcial se entera que será ascendido a guardia residente lo que le da el derecho de vivir en un pequeño apartamento dentro del Centro. Cipriano se niega a

mudarse por un tiempo, pero es algo inevitable, y pronto los tres se encuentran mudados dentro de su nueva casa.

El Centro les dice a los nuevos residentes que no lleven nada: “Aquí tenemos todo para ustedes: galerías, tiendas, escaleras mecánicas, puntos de encuentro, cafés, restaurantes… un carrusel de caballos, un carrusel de naves

espaciales, guardería, ancianato, un túnel del amor, un puente colgante, un tren fantasma… tiro al blanco, campo de golf, un mapa gigante, una puerta secreta… una muralla china, un Taj Mahal, una pirámide egipcia, un tempo de Karnak, un acueducto, fiordos, un río Amazonas con indios y todo … un caballo de Troya, una silla eléctrica… un gran enano, un pequeño gigante…” Todo incita a la gente a consumir para ser feliz, a deleitarse con el deslumbrante carnaval y desconectarse de cualquier compromiso real o logro, preguntar poco, sentir nada. Para Cipriano todos parecen estar anestesiados. Siente como si estuviera flotando, sin peso alguno, en un mundo ilusorio.

Cipriano recorre desorientado, sintiéndose como una reliquia, hasta que un día se siente tentado a tocar cierta puerta. Un guardia aparece y le dice a Cipriano que no hay nada detrás de esa puerta, “pero nos indica quien está sintiendo curiosidad en el Centro”. Cipriano está curioso y ahora más que nunca que algo inquietante parece estar a la mano.

Ya tarde una noche, Cipriano sigue a Marcial hasta un segundo sótano donde estaban taladrando y excavando mucho. Dentro de una cueva había un banco de piedra donde ve esqueletos humanos fijados con clavos de metal mirando hacia una pared. Los excavadores, al parecer, habían desenterrado un tesoro arqueológico: “La Alegoría de la Caverna” de Platón. “No quiero seguir viviendo aquí”, anuncia Cipriano. Siempre se sintió fuera de lugar en el Centro, pero de repente ve como su problema se reaviva, representa la causa de preocupación de cada uno de nosotros: ser engañados creyendo que sombras, reflejos e imágenes son una realidad, ser cegados por formas sin sustancia, actuar sin ninguna preocupación. Cipriano le dice a su hija y a su yerno que él no pasará el resto de sus días “amarrado a un banco de piedra mirando hacia una pared” como todos los demás.

Luego, toda la familia parte en un camión saltando a lo desconocido, como si los arrastrara un río. Marcial les comenta que cuando abandonó el Centro leyó un gran cartel que decía: PRONTO, LA ALEGORÍA DE LA CAVERNA DE PLATÓN ABIERTA ALPÚBLICO. UNA ATRACCIÓN EXCLUSIVA… COMPREN SUS ENTRADAS YA.

Todo un espectáculo y todo espectáculo empaquetado para la venta. Nada con sustancia o vitalidad o significado real. La odisea de la familia es hacia un mundo donde ellos podrán participar más activamente y vivir más plenamente, donde ellos estarán una vez más con los pies en la tierra y experimentarán el peso del mundo.

***

He intentado esbozar una pedagogía de esperanzas y posibilidades, un enfoque para enseñar por la libertad, el cual es, necesariamente, una pedagogía de conflicto y lucha. He descrito la enseñanza como un acto de devoción para ayudar a todos los seres humanos a que alcancen su humanidad, su iluminación y su liberación, pero a su vez como una forma de resistencia a la persistencia de utilizar la escolarización como un medio para obtener control y para

oprimir. Enseñar para humanizar, como ya he dicho, es una opción que es tomada por aquellos que enfrentan, clara y resolutamente, los obstáculos ante ellos, cuando llegan a comprender las dimensiones de lo que está en juego. Así, podemos entender la enseñanza como un sitio para la esperanza y lucha, como un espacio disputado que involucran ideas sobre el mundo que queremos tener y habitar a futuro.

Asimismo, argumenté estar a favor de ser explícitos en cuanto a nuestro compromiso moral ya que éste opera a un nivel más profundo y con una base más firme que, por ejemplo, las habilidades o disposiciones mentales. Sabiendo donde estamos parados y que representamos, deberíamos ser capaces de sortear las turbulentas aguas de la enseñanza y de la escolarización de una manera más efectiva y fiel.

Para mí, nuestro primer compromiso debería ser hacia nuestros estudiantes: nos ponemos de su lado. Nos ponemos del lado de ellos como aprendices, apoyando sus esfuerzos para ser más sabios, más capaces, más iluminados, y nos ponemos de su lado como ciudadanos, alentándolos en sus sendas hacia la libertad. Reconocemos y apoyamos la completa humanidad de nuestros alumnos. Nos oponemos a cualquier circunstancia que pueda degradarlos, minimizarlos o reducirlos.

Nuestro segundo compromiso es crear una república de muchas voces, un ambiente y una pedagogía que honre la humanidad de cada uno y que sea un lugar de encuentro para todos. Ahora toca otro compromiso fundamental, el sentir el peso del mundo sobre los hombros. Ya hemos puesto un ojo en nuestros estudiantes y el otro en nosotros. Tenemos un ojo en los espacios físicos, emocionales, sociales y políticos para la enseñanza. Pero ahora propongo que desafiemos la psicología y el sentido común para encontrar un cuarto ojo, el cual vamos a utilizar para observar el contexto mucho más amplio en que vivimos y trabajamos. Pienso que es una obligación.

***

La poeta Jane Hirshfield dice que la poesía puede ayudar a “encontrar un camino a una vida más larga de lo que tendrías que vivirla”. Esa vida más larga es tanto en el por dentro como por fuera y requiere de viajes al

interior de cada quien y compromiso en lo exterior. Los viajes al interior provocan a la imaginación que yace en el corazón del cambio. Sin imaginación todo está ahí, inmóvil y liso en la superficie, inerte, estático, inmutable.

Una persona intolerante podría ser definida de manera práctica como alguien cuya imaginación ha sido mutilada o asesinada. Pero con imaginación el mundo que encontramos no es más real que una pista de lanzamiento.

Por supuesto, ésta debe ser empleada en contacto con el mundo. Hirshfield motiva la activación interna, aún cuando ella rechaza cualquier clase de preocupación hacia uno mismo, “eso es narcisismo y no el camino a la sabiduría”, dice. El balance se encuentra a través de encuentros más amplios: “el peso del mundo solo lo puedes sentir al levantar tus propios brazos y hombros”, dice. El mundo es irreconocible hasta que es tocado, desconocido hasta que se experimenta. Nosotros percibimos el mundo, observamos su alcance, sus fronteras y las opciones que ofrece, y comprendemos nuestro lugar especial en él solo cuando lo sujetamos e intentamos levantarlo.

En un conflictivo y alocado poema de amor a Estados Unidos,

Langston Hughes describe el mundo según su perspectiva, con sus barreras y sus límites, con sus alambres de púas y sus barrotes, a medida que el siente el peso del mundo al levantar sus hombros y brazos. Comienza de esta manera:

Que América vuelva a ser América.

Que sea el sueño que solía ser.

Que sea el pionero en las llanuras

Que busca un lugar donde ser libre.

(América nunca fue América para mi)

Que sea el sueño soñado por los soñadores

Que sea esa grande y fuerte tierra de amor

Donde nunca los reyes intriguen y los tiranos conspiren

Para aplastar de arriba a los hombres

(Nunca fue América para mí).

Oh, que mi tierra sea la tierra donde la Libertad

No sea coronada con una falsa corona de flores,

Con una oportunidad real, y una vida libre,

Que la igualdad se respire en el aire.

(Nunca existió tal igualdad para mí,

Ni libertad en esta “tierra de libres”)

La imaginación de Hughes está tanto afectada como afinada por lo que se ha denominado la acusación social de negro en la América blanca. Hughes decide no huir de la acusación, sino más bien la asume, para abrazarla y plegarse a ella, para utilizarla para sus propios fines humanistas. Describe un mundo de muros y cadenas y, simultáneamente, sueña con la posibilidad del mundo que podría ser pero aun no es. Langston Hughes es para mí una luz brillante y clarificadora que me recuerda que ser completamente humano y libre significa utilizar los

obstáculos para alcanzar tu propia libertad, los impedimentos para expandir la humanidad y para resistir a las fuerzas que intentan reducir a las personas y categorizarlas para convertirlas en objetos. La verdadera sustancia de la

libertad se encuentra en las plazas públicas donde la gente se enfrenta una a otra con autenticidad, donde se unen para identificar y superar barreras. Esos son los espacios donde encontramos nuestras propias voces, potencialidades, poder y esperanzas.

A menos que vivamos en un mundo perfecto (y todo lo que yo se sobre mundos perfectos y utopías de cualquier tipo, ya he intentado vivir en más de una, es que nunca me sentiré satisfecho), parte de nuestro trabajo consiste en identificar los leones en la ruta hacia nuestra propia identidad. No tenemos que saber necesariamente que hacer, pero sabemos que las oportunidades para hacer bien están por todas partes. W.E.B. DuBois dijo: “Debemos quejarnos. Sí, una queja franca y directa, una agitación incesante, una demostración constante contra la deshonestidad y lo que está mal. Este es el viejo e infalible camino a la libertad y debemos seguirlo.” Tenemos

que quejarnos cuando observemos un sufrimiento injusto, dolor innecesario, una penuria no merecida, al menos deberíamos reconocerlo, mirar y escuchar. También podemos insistir en nuestro derecho de permanecer escépticos de cara a la credulidad, agnósticos y cuestionadores de los verdaderos creyentes. Aun así, en un mundo profundamente desbalanceado, hay situaciones más que suficientes para que cada uno de nosotros encuentre

que hacer.

Derrick Bell escribe en sus reflexiones sobre el activismo que “todo en la vida es temporal y lo aceptamos sin poner resistencia”. Debemos, continúa, buscar la satisfacción durante la travesía y encontrar nuestra integridad en la lucha porque no importa cuanto nos esforcemos por buscar la justicia nunca la encontraremos: “La perfección nos evadirá”. Siempre hay más por hacer y siempre habrá más por hacer.

Debido a que hay tanto por hacer, día a día me siento más atraído por los activistas: ese montón de andrajosos, rebeldes, soñadores, excéntricos, románticos e idealistas. La gente que dice estar en contra, siempre moviéndose en dirección de lo que ellos esperan que sea un mundo mejor, se definen a si mismos con las acciones. Mi imaginación, mi sentido de lo moral y de lo bueno, es nutrida y desafiada por aquellos que rompen con el sentido común de las multitudes y actúan a favor de algo más justo y más nuevo. “Todo en orden”, repite el pregonero todas las noches por cada cuadra. Pero la vocación activista nos recuerda que no todo está bien, así es amigos, todavía hay más que debe hacerse.

El activismo es tan vasto como la imaginación, tan profundo como el ser humano, tan osado como el corazón, el cual “es un músculo del tamaño de tu puño”, como dice la joven, brillante y dinámica Dalia Sapon-Shevin. El activismo no debe ser confundido con tácticas específicas, sino más bien una posición contra el mundo, una que capta nuestra atención de las cosas que tienen que arreglarse. Los activistas se comprometen, participan, contribuyen, se levantan, protestan, inician, se mueven, esas son sus principales características. Cuestionan la sabiduría recibida, se preguntan que podrá ser, pero no es suficiente así que actúan. Abren sus ojos, identifican las injusticias y las traen a la luz para que otros vean la verdad de las cosas más claramente. Dramatizan un hecho o envían un mensaje y crean un espacio

público donde la gente puede reunirse de manera auténtica para crear algo nuevo. Luego, participan con cada vez más público que está muy ocupado informándose y educándose. Toman riesgos no solo cuando infringen la ley,

también cuando ellos rompen con normas de educación o con la persuasión imperante en la tribu o multitud. A veces se niegan a participar así como a veces toman parte en cosas olvidadas por ellos, para así crear el mundo en el

cual ellos querrían vivir.

Los activistas aparecen en todos los capítulos de la historia de Estados Unidos: El Motín del Té en Boston, las batallas de Lexington, los ferrocarriles subterráneos, la toma del arsenal de Harpers Ferry, la revuelta de Haymarket, el movimiento por el sufragio femenino, Flint, Selma, Atlantic City, Tierra del Sur. Los activistas se negaron a participar en algunos hechos quemando sus cartillas militares. Algunos fueron a la cárcel por negarse a enlistarse en el ejercito para ir a la guerra en Vietnam o cuando, aquellos que pelearon en Vietnam, tiraron sus medallas en la Casa Blanca en señal de protesta por lo que ellos ahora consideraban una aventura inmoral.

Asimismo, los activistas tomaron parte en hechos que estaban oficialmente prohibidos en el Sur segregacionista. Recrearon el mundo que ellos imaginaban en autobuses y oficinas públicas, anunciando que aquellos actos

representaban la manera en la cual iban a vivir: negros y blancos juntos. Estas fueron expresiones auto-transformadoras y a su vez expresiones que transformaron al mundo.

El Movimiento de los Derechos Civiles creó la agenda moral para una generación y se convirtió en parte del paisaje y del aire que respiraba la gente. Las nociones de libertad, liberación, justicia social y paz pasaron a ser más que abstracciones, de hecho, se personificaron y se convirtieron en cosas reales y concretas para ser promulgadas y para vivir. La democracia participativa fue algo para vivir, respirar y experimentar en el diarismo al igual que sucedió con la insurrección cultural que le sucedió. Toda esta gente simplemente se veía a sí misma como personas que estaban rompiendo las barreras que les habían impuesto y que les impedían alcanzar su humanidad plena, individuos que soñaban más allá de las fronteras y por lo tanto transgredían los límites de lo establecido. Muchos han vivido como si ya estuvieran en el mundo que ellos desean, reticentes a suplicar poder o rogar por el fin de la injusticia (deberíamos poder sentarnos en el mostrador de este restaurante para ordenar comida y así lo haremos; las escuelas deberían

ser sitios enfocados en la liberación de los niños, así las construiremos) y con tales acciones han ayudado a crear el mundo de sus sueños. Gran parte de este cruce de fronteras involucra un cambio radical en la conciencia, un

rechazo tanto a la corriente conservadora como a los reformistas liberales y a favor de una transformación personal y estructural más fundamental. El mundo de las posibilidades abierto ante nosotros.

Y el trabajo sigue y sigue: protestas constantes en la sede de la OMC; movilizaciones en contra de la guerra; foros para discutir temas controversiales, blogs y revistas de poca circulación; miembros del Frente de Liberación de la Tierra sentándose en frente de los tractores para evitar que los bosques sean destruidos; tiendas de campaña en los campus de las universidades para protestar por los niños explotados laboralmente que manufacturan los uniformes escolares; ciclistas de la organización llamada Masa Crítica cierran la autopista Lake Shore Drive en Chicago, lo cual

conlleva a que la gente no salga en sus carros ese día; homosexuales y gente que los apoya llenan los pasillos de la Gobernación de Massachusetts; artistas del lado oeste de Chicago pintando sobre publicidades de tabaco y alcohol con jeroglíficos urbanos que contenían mensajes importantes sobre la salud pública. Movilizándonos, dramatizando, negándonos, insistiendo, comprometiéndonos, arriesgando… Y a veces, cuando no sabemos que hacer, simplemente siendo testigos. Por ejemplo, a principios de la crisis del SIDA, cuando el virus no había sido ni siquiera identificado y antes de que la protesta pudiera ser claramente articulada, un grupo de activistas creó el impactante y hermoso Proyecto Edredón. Así como los escuadrones sanitarios en La Peste de Albert Camus, el Proyecto Edredón dijo: Porque tenemos que hacer algo, miraremos y escucharemos, prestaremos atención y seremos testigos, más que nada, nos negamos a no poder remediar nuestro sufrimiento.

Pero cualquier afirmación sobre lo correcto de un acto yace en la solitaria rectitud de lo que se demanda, en actuar contra la injusticia a favor de algo mejor. Dorothy Day, fundadora del Movimiento Católico de Trabajadores y activista atareada toda su vida, dijo, “estoy trabajando por un mundo en el cual se le haga más fácil a la gente comportarse decentemente”. No perfecto sino mejor.

El activismo nos empuja hacia el mundo de las posibilidades morales, pero no tiene un valor propio ni da valentía ni drama ni resistencia. Ni siquiera la virtud proclamada u obvia de sus actores tiene valor por sí sola. Al final, todo depende de la verdad de los asuntos que se expongan, se describan o a los que uno se oponga ¿Acaso la acción resiste heridas injustas, sufrimientos innecesarios o el dolor que puede ser evitado? ¿Acaso la acción abarca o al menos otorga espacio para el cambio? ¿Ha educado a otros?

Ésta última es la pregunta por la cual el activismo es medido. Aunque no hay manera de saberlo de antemano, representa la parte esencial del crecimiento posterior: ¿La acción tomada informó, iluminó, alteró o expandió

nuestra conciencia colectiva?, ¿Educó a participantes y testigos?, ¿Sirvió para construir una comunidad más amplia?

Por lo tanto, el activismo es cuando menos un evento pedagógico conectado a la educación. Los activistas intentan enseñar y los educadores abren posibilidades para una variedad más amplia de opciones. Therese

Quinn, profesor del Instituto de Arte de Chicago, ha creado junto con sus estudiantes una serie de afiches deslumbrantes que conjugan la enseñanza con el activismo. Cada afiche tiene una foto de algún educador/activista

(Paulo Freire, Myles Horton, James Baldwin) y alguna cita de alguno de sus trabajos junto con una osada invitación: “Se un activista/Se un educador.Cambia el mundo”. La cita que seleccionaron de Horton decía lo siguiente:

“Una buena educación radical… no tiene nada que ver con métodos o técnicas, sino en colocar al amor en primer lugar… Y eso incluye a cualquier persona en cualquier parte, no solo a tu familia o a tus compatriotas o a los

de tu propia raza. Significa desear para ellos lo mismo que deseas para ti. Luego sigue el respeto a la capacidad de la gente de aprender, de actuar y de moldear sus propias vidas. Tienes que tener confianza en que la gente puede

hacerlo. El tercer punto consiste en valorar las experiencias de los demás. Tu no puedes pedir que se respete a la gente si tu no respetas sus experiencias”. Quinn continúa reclutando artistas para su programa de Educación

Artística y ella obtiene algo más profundo que un simple trabajo. Para ella, la enseñanza está llamada a cambiar el mundo.

***

La alemana socialista Rosa Luxemburgo, en una carta enviada desde la prisión a un amigo, dijo lo siguiente acerca de llevar una vida balanceada y ser activista: “¡Míralo como que tu sigues siendo un Mensch! Ser un Mensch significa tirar la vida de uno ‘a la buena de dios’ de ser necesario, pero a la vez, disfrutar de cada día soleado y de cada bella nube…” Ella le hace un llamado a su amigo para que sienta el peso del mundo junto con su belleza.

Justo después de los ataques terroristas del 11 de septiembre hubo una apertura y curiosidad inusual entre muchos estadounidenses, un impulso para intentar captar la magnitud de los hechos, para sentir el peso, pero también para pasar del estado de shock a la comprensión, a la posibilidad de despertar. No había duda que había ocurrido algo inmenso, pero ¿De dónde vino y cómo se podía medir según la escala de horror global? ¿En qué clase de mundo vivimos?

Yo estaba agradecido de ser maestro, porque un maestro, no importa que suceda, siempre asiste a sus clases. El enseñar me dio un lugar a donde ir, un lugar donde estar, gente con quien hablar y con quien pensar. Siempre

les digo a mis estudiantes que tenemos que tener un espacio seguro para nosotros en nuestra clase, un espacio para la consulta, para la búsqueda de la verdad y del alma. Debemos dirigirnos a los demás con respeto, insisto, con la esperanza de ser escuchados y comprendidos y a su vez escuchar al otro con la posibilidad de que sus palabras nos lleguen o incluso que nos cambien. En las semanas después del ataque, todos nos sentíamos agresivos y agraviados, así que les dije a mis estudiantes que debíamos esforzarnos por ser más gentiles, más preocupados, y que de seguro íbamos a escuchar múltiples estallidos emocionales, pero debíamos resistir tanto como pudiéramos a cualquier gesto de arrogancia moral y sustituirla por compasión, generosidad e imaginación. Les pedí que dibujaran a pulso un mapa del mundo y para todos ellos habían vastos espacios en blanco casi por todos lados: África del Norte y Asia Central, los Balcanes y el Medio Oriente, el Golfo Pérsico y los países musulmanes. En esos espacios en blanco yace el

fracaso de la educación, quizás, la falla de profesores anteriores para servir de inspiración o para informar; o quizás esos espacios revelen un problema que acompaña el fácil confort de vivir en el regazo del privilegio ¿Quiénes somos en este mundo? Nos preguntamos ¿Cuáles son nuestras opciones en el mundo?

Los estadounidenses somos famosos en el mundo por no tener sentido de la historia ni de la geografía ¿Quiénes somos en este mundo? ¿Dónde estamos? Estas preguntas causan una vaga sensación de satisfacción o de desagrado, todo depende de cada quien, pero para la mayoría simplemente le es indistinto. En lugar de curiosidad, estudio, análisis o al menos una valoración honesta de las lagunas y confusiones, todo lo que tenemos son bandas marciales y banderas que ondean, lemas publicitarios, pequeñas frases y relaciones públicas: “la única superpotencia mundial”, “la nación más grande sobre la Tierra”, “el país de la libertad y de la democracia”.

Hace poco, escuché una entrevista que le hicieron a un soldado en Irak: “Estamos orgullosos de lo que hemos hecho aquí. “Todavía hay mucho por hacer, pero cuando llegamos aquí no había nada”. Está hablando de la Cuna de la Civilización. Uno puede decir cualquier cosa de Irak, pero “que no había nada” está definitivamente fuera de lugar ¿Quiénes somos y dónde estamos?, ¿Qué está pasando?, ¿Cuáles son mis opciones?

(continuara………)

Users Today : 21

Users Today : 21 Total Users : 35460284

Total Users : 35460284 Views Today : 26

Views Today : 26 Total views : 3418994

Total views : 3418994