USA / May 20, 2018 / Author: Katrina Schwartz / Source: KQED News

In the classroom, good teachers constantly test small changes to class activities, routines, and workflow. They observe how students interact with the material, identify where they trip up and adjust as they go. This on-the-fly problem solving is so common in classrooms many teachers don’t realize they’re even doing it, and the expertise they are gathering is rarely taken into account when schools or districts try to solve larger, systematic problems.

In education research, researchers come up with ideas they think will improve teaching and then set up laboratory experiments or classroom trials to test that idea. If the trial goes well enough that idea gets put on a list of research-approved practices. While research-informed practices are important, this process can often mean that the interventions are unrealistic or disconnected from the hectic reality of many classrooms, and are rarely used. But what if teachers themselves were the research engine — the spark of continued improvement?

The Carnegie Foundation is trying to bridge that gap in identifying techniques that work and «create a much more democratic process in which teachers are involved in identifying and solving problems of practice that matter to them,” said Dr. Manuelito Biag, an associate in network improvement science at the foundation. Biag previously worked on developing research-practitioner partnerships for Stanford’s Graduate School of Education.

For the past several years, under the leadership of Dr. Tony Bryk, Carnegie is trying to apply a structured inquiry process to problems in education, building the capacity of teachers, principals and district administrators to continuously improve. This type of improvement science started in manufacturing and has been used to successfully change human-based systems like healthcare.

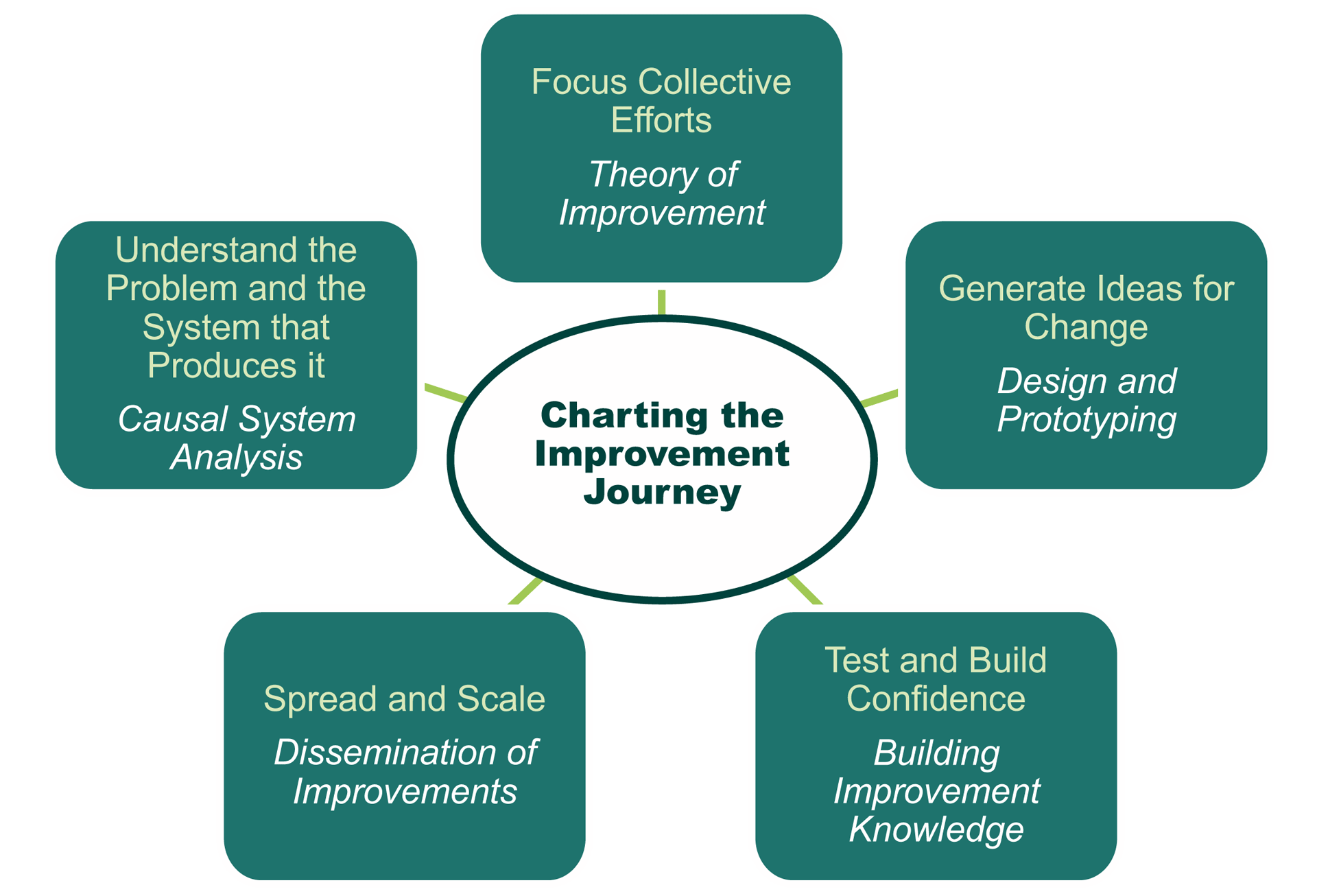

The basic tenets of the process involve understanding the problem, defining a manageable goal, identifying the drivers that could help reach that goal, and then testing small ideas to change those drivers. When done in a network, this cycle of improvement is expedited as various participants test different change ideas and share their findings with the group. Through a constant interplay of these elements a few change ideas will rise to the top and can be scaled across a system.

UNDERSTANDING THE PROBLEM

Many of the biggest problems of practice have been around a long time and aren’t easy to solve. Too often when trying to improve something leaders jump to solutions before properly examining the problem. Understanding the problem requires valuing many types of knowledge. It means doing empathy interviews with participants in the system including teachers, staff, parents, and students. It involves bringing the best research literature to bear on the problem. And sometimes representing the processes involved in the problem can illuminate areas that are breaking down.

Biag said this stage is crucial and shouldn’t be rushed. He’s seen improvement projects that require up to a year of study to fully understand the problem, its root causes and the levers of change available to leaders. Often an improvement network will know it’s time to move on when participants feel saturated — they aren’t turning up any new perspectives or information.

“Sometimes it’s good to stop doing the research and try something,” Biag said. Implementing some change ideas often helps inform the problem and may even necessitate that the team revisit and revise the problem statement.

DEFINE THE GOALS AND FOCUS COLLECTIVE EFFORT

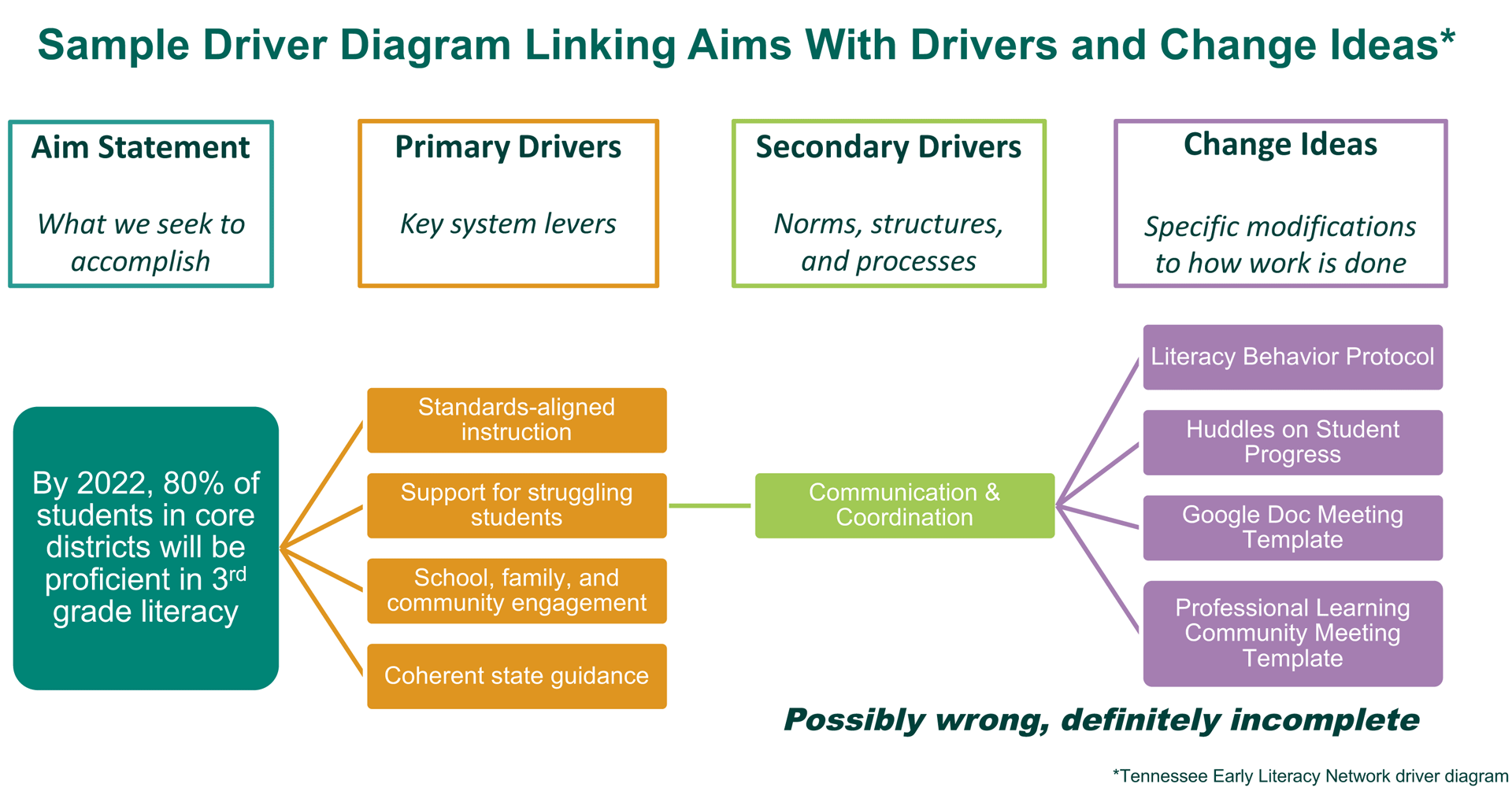

Once the group has a “good enough” understanding of the problem it’s crucial that they write a clear, succinct aim statement. It should be specific, measurable and focus on a challenging problem, but it should be doable.

The crucial question, Biag said, is “What’s within your span of control and what’s not? So when you act on this problem you aren’t wasting your time on the things that aren’t in your control.”

He often sees people define the problem too broadly. If the problem is an achievement gap between student populations, a group might say the root problem is inequality or poverty. Those things may contribute to the problem, but they aren’t within the control of teachers or principals or even districts to solve. A more manageable aim statement might be: “By June 2020 we’re going to increase from 45% to 90% the number of male students enrolling in credit bearing math courses at community colleges.”

“It has to be motivating enough for people to continue working on it for several months,” Biag said about the reach goal. But it must be specific and concrete enough that the group can see if change ideas are helping progress towards the goal.

“While an aim statement can look deceptively simple, you need to build trust and get on the same page with everyone in your network to even agree on where to focus your efforts,” Biag said. The network itself is important because it accelerates the pace of learning about potential solutions.

Once the aim is clear, the group brainstorms three to five primary drivers of the problem. These are the things the group believes provide the most leverage to meet the goal, and that are within the span of control. It’s crucial to only have a few of these, not twenty, because the network must work on all of them in tandem. Staying focused allows for more progress.

After identifying the most important drivers, network participants brainstorm change ideas that might affect those drivers. “The word change is very specific to improvement science,” Biag said. “It means an actual change in how you do work.” In other words, the focus is on the process and results in action. Change ideas are not things like “more money” or “more staff.” “It’s an actual change of a process or the introduction of a new process,” Biag said.

TEST AND BUILD EVIDENCE

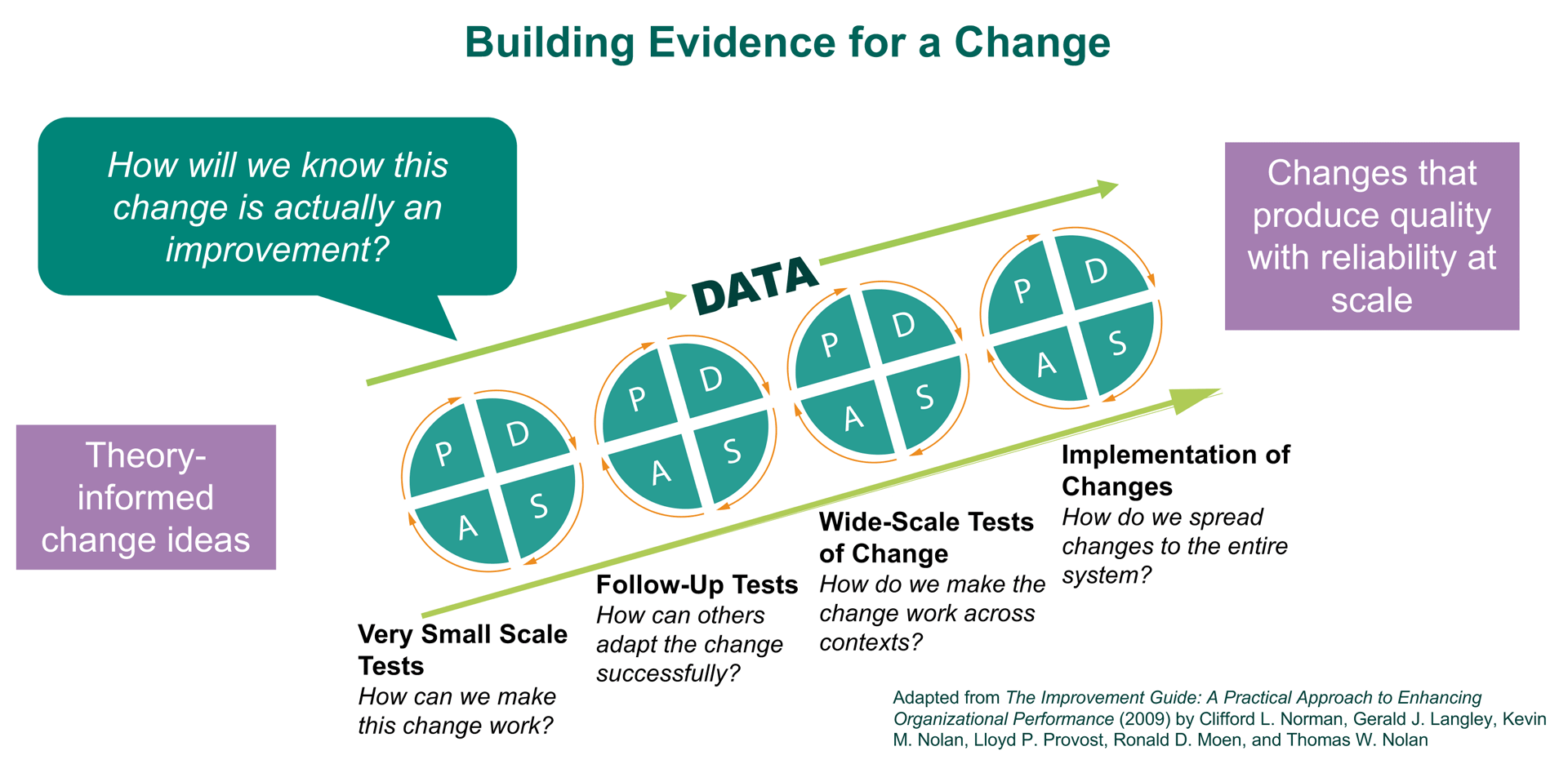

Once the group has a good understanding of the problem, its root causes, what drives it and some ideas that will directly affect those drivers, it’s time to start testing them. Carnegie uses a “Plan, Do, Study, Act” (PDSA) cycle for testing ideas. The changes should be fairly small and the tester collects data along the way. It doesn’t have to be complicated data, just something to help analyze and track whether the change is moving the needle.

“Most schools and districts plan plan plan, then do, and then they never study,” Biag said. He advocates that planning include a prediction because participants are more likely to compare a new strategy with the expected effect. If the change idea didn’t function as expected there’s a lot to learn there.

Many of the best change ideas come from looking at what Carnegie calls “positive deviants” — the bright spots in a network. For example, if a network sets the aim of improving college readiness for English language learner students, when leaders are assembling their knowledge base they should talk to teachers who seem to be achieving better than average results with that population. Those teachers are “positive deviants” and networks should try to learn from the ways their practices differ from colleagues.

For example, High Tech High Charter Network leaders identified that they wanted to increase the number of African American and Latino males applying to four-year colleges. When they looked at drivers, they realized school attendance was lower for this group and hypothesized that the way teachers communicated with parents might be part of the issue. To try to eliminate variation in parent-teacher communication they tested a change theory that involved using a set of protocols for interacting with families.

They went through several iterations of the protocols, but when they hit on one that seemed to work they spread it throughout their network of schools. Now, when teachers meet with parents around achievement or discipline they all try to make it positive, share data about the student, and co-construct an action plan with the parent, among other things.

The key thing about working in a network is that different people can be trying different change ideas and sharing their data. “The idea is that you’re not all working on all the same things at the same time,” Biag said. “So you leverage the network, and the power of the network, to increase change ideas.”

Some ideas won’t work and will be abandoned. Others might seem promising, but more data is needed, so others in the network might try them too. Over time the change ideas that seem to really impact the drivers rise to the top.

“As you’re testing and building evidence you’re going to find ideas that work and then you can talk about spreading those ideas,” Biag said.

SPREAD AND SCALE

Even with the best ideas implementation can be hard. Biag said leaders need to weigh several factors when thinking about how to spread an idea that seems to work. How costly will it be to implement? What are the consequences of failure? How reluctant are the people involved? How confident is the leader in the change idea?

For example, if the change is a parent meeting protocol and the leader doesn’t think it’s a great idea and that the cost of failure will be high, perhaps she only tests it on her sister first. But, if teachers are ready for the change and there’s nothing to lose, then maybe the idea can scale up more quickly. This is where knowing one’s own system and culture becomes important.

It’s also worth thinking about who within the system needs to be on board for the plan to go well. Those folks can be powerful advocates if convinced that the change idea is a good one. “The best people are those who were pretty skeptical in the beginning and you were able to change them,” Biag said.

Another strategy is to roll out the idea with those eager to try it and then demonstrate success to those who are more fearful. It’s also necessary to be humble and willing to go back and test new ideas if the ones that seemed to work in the smaller group don’t work when scaled. Perhaps the aim statement needs to change, or maybe the drivers aren’t actually the most impactful.

“Our theory is possibly wrong and definitely incomplete; that’s kind of a Carnegie saying,” Biag said. He doesn’t want anyone to think this process is linear, rather it’s a cycle. And when people get comfortable with the cycle they build it into everything they do naturally. The biggest strength of continuous improvement is that it offers a path for systemic change, a way to build the capacity within the system, rather than building whole new systems.

“What we’re trying to do is implement these tools and ways of thinking to empower people to engage in this work,” Biag said. And that means having a bias towards action.

“You have to start before you feel ready. Your understanding of the problem will change over time and when you act on that problem the problem will change and so your understanding of that problem will change,” Biag said.

People learn how to think about continuous improvement through the process of doing it. They get better at narrowing in on motivating, but achievable aim statements. They learn to include more voices in the information gathering stage. The “Plan, Do, Study, Act” cycles become second nature, and analyzing data gets less scary.

Perhaps one of the best parts of continuous improvement is that it helps empower those within a system to see themselves as the drivers of change. The ideas come from practice as does the data. And while data is often associated with accountability requirements, this improvement process offers practitioners the opportunity to think about and evaluate data that are important to their practice.

In this process, the data is only worthwhile if it shines light on whether the change is working. And when data is used this way, it’s easier for educators to be transparent about what they’re seeing. Improvement is not about judgement, it’s a constant, normal aspect of professional life.

“You have to have a lot of humility to come to the realization that you don’t have the answers, and that you’re going to learn your way into this,” Biag said. “You’ve got to think about this as a learning journey. If you really had the answers to this problem we wouldn’t be talking about it.”

To see measurable progress on some of the most intransigent problems in education requires a systematic focus on improving in every aspect of the system. It’s not enough for one teacher to be amazing, or one school to outshine the others around it. All kids deserve an incredible education; and that can only happen by building on the strengths already found in the system.

Source:

https://www.kqed.org/mindshift/51115/how-to-plan-and-implement-continuous-improvement-in-schools

Users Today : 12

Users Today : 12 Total Users : 35474674

Total Users : 35474674 Views Today : 17

Views Today : 17 Total views : 3574665

Total views : 3574665