Europa/Francia/Diciembre del 2017/https://theconversation.com/

L’automne n’est décidément pas une bonne saison pour l’École française. Les enquêtes PISA apportent régulièrement leur lot de nouvelles préoccupantes sur les performances en mathématiques des élèves de 15 ans. Pour ce qui concerne la lecture, les résultats de l’enquête Pirls (Programme international de recherche en lecture scolaire, touchant les écoliers de CM1) n’étaient pas très bons en 2012 (cf. Le Monde du 13/12/2012). Ceux de 2017 sont encore plus mauvais, au point de déclencher une prise de parole quasi immédiate du ministre de l’Éducation nationale.

La prise en compte des données apportées par ces enquêtes, dont le caractère préoccupant est indéniable, impulse logiquement une double recherche : des responsables ; et des solutions. On peut admettre qu’une partie de la responsabilité (au moins) appartient à la pédagogie, et qu’en conséquence une partie de la solution est d’améliorer celle-ci. Mais alors, comment ? Les pistes proposées par le ministre, avec en particulier la création d’un Conseil scientifique de l’éducation nationale (CSEN), sont-elles les bonnes ?

De la nécessité d’une « pédagogie vraiment éclairée »

Commentant déjà des résultats produits par des enquêtes PISA et Pirls, [Antoine Prost (Le Monde du 21 fevier 2013) « sonnait le tocsin », en reconnaissant que le niveau scolaire baissait vraiment. Mais il avertissait que le « vrai problème de pédagogie » que nous avons « ne se résoudra pas en un jour ». Et ajoutait que la seule façon d’« enrayer cette régression » est de « faire travailler plus efficacement les élèves ». Ce qui nous semble incontestable.

Pour rendre l’école plus efficace, il apparaît donc à la fois nécessaire, et urgent, de travailler à l’émergence de ce que Marcel Gauchet a désigné (Le Monde du 22 mars 2013) comme « une pédagogie véritablement éclairée », laquelle, pour lui, restait à inventer. Or, si nous ne savons toujours pas comment enseigner de façon vraiment efficace, c’est essentiellement, avertissait Gauchet, parce que nous ne savons pas encore ce que veut dire apprendre.

La recherche d’une plus grande efficacité exige ainsi un déplacement de curseur, d’une focalisation sur l’acte de « transmission » du professeur, à une focalisation sur l’acte d’appropriation qu’opère l’élève qui apprend, dans l’espoir de donner un fondement solide à cet acte. C’est pour atteindre cet objectif que Monsieur Blanquer mise sur « la lumière des sciences ».

Enseigner à la lumière des sciences ?

La tâche prioritaire de la pédagogie est bien alors aujourd’hui de se centrer sur l’acte d’apprendre, en étant éclairée par toutes les disciplines pouvant légitimement apporter un savoir utile, qui soit susceptible de donner consistance à l’activité d’enseignement, laquelle a pour fin principale de faciliter le déploiement de cet acte d’apprendre. Avec l’espoir de sortir du débat d’opinion, en s’appuyant ainsi « sur ce qui est prouvé et ce qui marche à la lumière des sciences » (J.-M. Blanquer le 24 novembre 2017).

Mais, alors, il y a lieu de s’interroger sur le sens, et la portée, de l’expression « lumière des sciences ». Car il ne faudrait pas perdre de vue deux considérations qui nous paraissent essentielles, et de nature à prévenir des empressements excessifs, ou des choix contestables. La première est que toutes les contributions seront les bienvenues, et qu’aucune approche n’a le monopole de la connaissance de l’« apprendre ». La seconde est que, bien qu’il soit indispensable, un éclairage par les sciences n’a aucun pouvoir automatique de transformation des pratiques pédagogiques : la pédagogie sera toujours à inventer.

Les neurosciences n’ont pas le monopole de l’« éclairage »

Pour progresser vers une « pédagogie vraiment éclairée », trois apports (et non un seul) nous semblent aujourd’hui précieux.

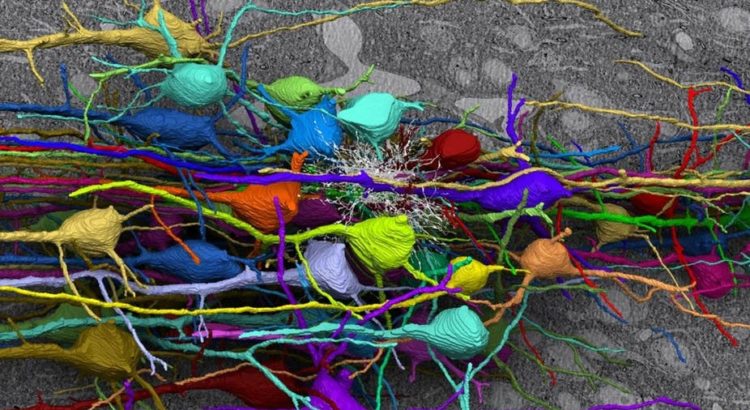

Le premier est, en effet, celui des connaissances produites par la neurobiologie. Si les tenants d’une neuro-éducation, d’une part vont souvent un peu vite en besogne, et d’autre part se laissent trop facilement prendre au mythe d’une possible éducation scientifique, il n’en reste pas moins vrai que l’acte d’apprendre a une dimension neuronale incontestable, que le cerveau y joue un rôle essentiel, et que tout ce qui nous aide à comprendre les mécanismes cérébraux est utile à la progression dans la connaissance des conditions de construction des savoirs comme outils ou objets mentaux.

Ayant moi-même souligné, dès 1984, l’apport décisif des travaux de Jean‑Pierre Changeux pour la connaissance des processus d’apprentissage (« Neurobiologie et pédagogie : « L’homme neuronal » en situation d’apprentissage », Revue Française de Pédagogie, N° 67, 1984), je ne peux qu’approuver Stanislas Dehaene (devenu depuis Président du nouveau CSEN) lorsqu’il insiste (Le Monde du 5/11/2011) sur la nécessité de « prendre en compte les avancées de la recherche » en ce domaine. Mais à la condition expresse de ne pas croire que ces avancées feront de l’activité d’enseignement une science.

Un deuxième éclairage est apporté par les travaux portant sur l’apprentissage autorégulé (self-regulated learning ou SRL), qui ont permis de comprendre en quel sens l’autorégulation pouvait être vue à la fois comme un fait fonctionnel fondamental, et comme un idéal pour l’action éducative. Horizon d’une activité d’enseignement se voulant efficace, la maîtrise par le sujet qui apprend de ses propres processus d’apprentissage est aussi le moyen de tendre vers cet horizon (Hadji, 2012).

Enfin, la révolution numérique apporte un troisième éclairage. Si les outils et possibilités nouvelles qu’elle offre ne sont pas automatiquement synonymes de révolution pédagogique, et s’il ne faut pas croire que les nouvelles technologies pourront tout résoudre, la mise en œuvre des possibilités offertes par ces technologies nous permet de redécouvrir les trois grandes caractéristiques d’un apprentissage efficace : un apprentissage actif, contrôlé par le sujet lui-même, et à forte dimension collaborative.

Enseigner n’est pas une science

Mais, s’il existe, selon les termes de Stanislas Dehaene (Le Monde des 22 et 23 décembre 2013), « une approche scientifique de l’apprentissage », cela ne permet nullement de conclure avec lui qu’« enseigner est une science » ! L’efficacité éducative ne peut pas être prouvée a priori. L’utilité des pistes proposées par la neurobiologie, l’apprentissage autorégulé, et la révolution numérique, demandera à être éprouvée dans une mise en œuvre « expérimentale ». Il faut essayer, pour voir si vraiment « ça marche ». L’évaluation, nécessaire, ne peut venir qu’a posteriori, et n’apportera, compte tenu de la multiplicité des facteurs en cause, et de la difficulté, pour ne pas dire de l’impossibilité, d’établir des « groupes contrôle » (« Les dossiers de la DEPP », 207), qu’une « preuve » toujours relative et limitée de l’efficacité d’une stratégie éducative.

Les situations d’apprentissage sont toujours à inventer. Mais telle est justement la vocation de la pédagogie, comme « invention minutieuse et obstinée de dispositifs utilisables ici et maintenant », selon la belle formule de Philippe Meirieu (Meirieu/Cédelle, 2012, p. 183). Même si l’on se fondait sur une parfaite connaissance de l’acte d’apprendre, l’élaboration, et la mise en œuvre, de situations susceptibles d’optimiser cet acte, relèveraient encore et toujours d’un certain bricolage.

Ainsi, bien que la pédagogie, comme pratique, puisse trouver un fondement solide dans les apports des sciences éclairant les différentes dimensions de l’acte d’apprendre, l’approche scientifique de l’apprentissage n’a pas le pouvoir de faire de l’enseignement une science. Le légitime désir de dépasser le débat d’opinion ne doit pas nous jeter dans les bras d’un scientisme illusoire.

Fuente:

https://theconversation.com/pour-lecole-et-les-resultats-scolaires-les-neurosciences-feront-elles-le-printemps-88934

Fuente Imagen:

https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/WfisCiGAFTbrOpN-sh-FERTIIL9WtGnrv39cJfqFErscaBJGjUTlaCmNVMfPRNV0elLxdw=s114

Users Today : 16

Users Today : 16 Total Users : 35475041

Total Users : 35475041 Views Today : 19

Views Today : 19 Total views : 3575235

Total views : 3575235