Elize’a Scott, a Key Elementary School third grade student, right, reads under the watchful eyes of teacher Crystal McKinnis, left, Thursday, April 18, 2019, in Jackson, Miss. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

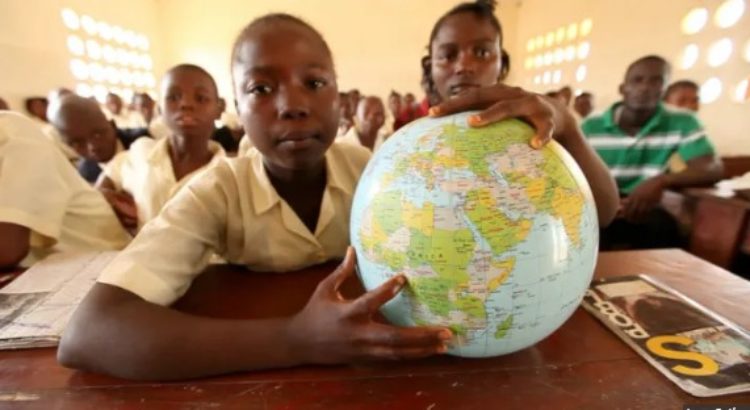

UNICEF

Recently, the news has been full of headlines on the disparities that exist in the American education system. Some wealthy parents — including actresses Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman — have been indicted for gaming the admissions process for their children to some of the nation’s top colleges. Last week, Loughlin pleaded not guilty to charges of conspiracy to commit fraud and money laundering. Meanwhile in New York City, only 7 black students were admitted to the city’s most selective public high school — out of 895 spots. Currently, Harvard University is being sued over its affirmative action admissions policies.

The beleaguered American education system has struggled for years to address issues of inequality, with little success. A new report from the education research and advocacy group EdBuild finds that there is a $23 billion gap in funding between white and non-white school districts of equal size (the report identifies white school districts as those with 75% or more white students).

“What’s happening here is you are seeing a continuation of what we’ve found in previous reports: the foundation of the education funding system does not serve to best represent the interests of students from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds,” said Matt Richmond, chief program officer at EdBuild.

The wealth gap

But even when EdBuild looked at districts of similar wealth levels, it found there were big differences that cleaved along racial and ethnic lines, with minorities receiving less than their white counterparts.

“In the U.S., race and economics tend to be correlated,” he said. “What was even more disappointing was that even when you accounted for poverty, there was still a difference of about $1,500 per student, even in high poverty school districts.”

The problem, the report points out, is the way public schools are funded. According to Richmond, 45% of funding comes from local sources, while 45% is provided by the state. The final 10% is made up of federal government funding.

With school budgets tied to the local tax base, wealthier communities are able to provide more funding for their local school districts.

“In a way, that’s systemic and formulaic,” Richmond said. And the wealth gap between communities is too large for the states to bridge, he said.

“If you look at the distribution [from states],” Richmond continued, “for the most part you find it’s relatively progressive. More money is going to districts with less wealth. You do see the states trying. But they have a tendency to fall short.”

But according to a 2018 report from the Rutgers Graduate School of Education and the Education Law Center, school funding isn’t as progressive as it needs to be. The report shows that funding disparities between states isn’t shrinking, but instead growing. “The funding differential between the highest (New York) and lowest (Idaho) funded states is over $12,400,” the report states.

The report goes on to say many states are becoming more “unfair” in their funding. “In 2015, only 11 states had progressive funding systems, down from a high of 22 in 2008,” the report says.

These gaps disadvantage already disadvantaged children.

In this photo taken Oct. 20, 2017, K-4 students Devon Daniels, left, and Charlie Webb talk to teacher Dana Chrzanowski at Milwaukee Math and Science Academy, a charter school in Milwaukee. Charters are vastly over-represented among schools where minorities study in the most extreme racial isolation,

Children from lower-income communities are less likely to be enrolled in earlier education, while teacher salaries — already lower than their non-teacher counterparts — are more competitive in states and districts with more funding, attracting higher-quality teachers. But according to the report, one of the most “meaningful” outcomes of fair funding is student-teacher classroom ratios.

And that’s not all. The Washington, D.C.-based think tank Urban Institute has found that children “from high-wealth families (defined as total family wealth including home equity above roughly $223,500) are more than one and a half times as likely to complete at least two or four years of college by age 25 as those in low-wealth families (wealth below $2,000).” And once they make it into college, children from high-wealth families are nearly twice as likely to graduate from a four-year institution — compared to less than a quarter of students from low-income households.

Fuente de la Información: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/americas-true-education-scandal-poor-minority-children-continue-to-be-left-behind-in-public-schools-160517019.html

Fuente de imágenes: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/americas-true-education-scandal-poor-minority-children-continue-to-be-left-behind-in-public-schools-160517019.html

Users Today : 37

Users Today : 37 Total Users : 35460340

Total Users : 35460340 Views Today : 53

Views Today : 53 Total views : 3419081

Total views : 3419081