Maximiano Millán G.

Para cualquier persona del común y silvestre mundo que nos rodea al preguntarle su opinión sobre la calidad de la educación venezolana, con una alta probabilidad emitiría un juicio de valor negativo en cualquiera de sus subsistemas existentes.

Al mismo tiempo, podemos también tropezarnos con un sinnúmero de trabajos en donde se plantean nuevas metodologías, excelentes explicaciones de la problemática hacia dentro de las aulas, didácticas mejoradas y mas enraizadas en el entorno de los estudiantes, muchas de las cuales son de vieja data, digamos al menos de más de treinta años.

Si este problema fuera solo de Venezuela o de la mayoría de los países de Latinoamérica, podría sospecharse que nuestra condición de país dependiente es una fuerte causal del problema. Pero desde el otro lado del Atlántico nos llegan quejas del mismo tenor, veamos:

“Los alumnos no sólo terminaban sus estudios sin saber resolver problemas y sin una imagen correcta del trabajo científico, sino que la inmensa mayoría de ellos ni siquiera había logrado comprender el significado de los conceptos científicos más básicos a pesar de una enseñanza reiterada” (Gil Pérez y de Guzmán Ozámiz, 2001, 36)

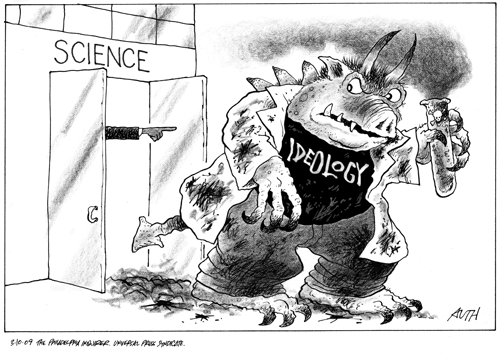

Aclaramos que en el estudio anteriormente citado los estudiantes a que se refiere son los egresados de la básica española. Aunque resulta obvia la relación histórica entre España y Latinoamérica, el que tanto allá como acá el problema educativo planteado tenga aristas muy parecidas, nos hace pensar que estamos ante un problema que tiene que ver más con el paradigma educativo al cual estamos amarrados, que con el tipo de reforma o innovación educativa aplicada.

Estamos por tanto, ante la existencia de un modelo de enseñanza paradigmático que se ha mantenido en el tiempo y que se ha salido con la suya todas estas décadas, permitiéndonos realizar renovaciones y modificaciones que no resolvieron para nada el problema de la calidad en la educación.

Es necesario entonces darle nombre a este problema paradigmático. Y más importante, a nuestro humilde entender, es descubrir los procesos que le han permitido mantenerse en el tiempo.

En sana lógica de la metodología marxista, necesitamos entonces encontrar las leyes que han creado este paradigma educativo y que le ha mantenido durante décadas formando a nuestros estudiantes para “no saber”. Nos interesa además, y sobre todo, la ley que rige sus cambios, su evolución, es decir, el tránsito de una forma a otra, de uno a otro orden de interdependencia. (Marx, 1867, 8)

Observemos este problema desde diferentes perspectivas en función de conocer, el tamaño de la estructura, que creó este paradigma, desde cuatro perspectivas. A fines de esta primera publicación, se abordaran dos de ellas.

-

La perspectiva burocrática.

Cuando los gobiernos occidentales hicieron de la educación una política de Estado, transfirieron al sistema educativo, los elementos básicos del modelo weberiano sobre la burocracia. Creando así el sistema burocrático educativo que conocemos hasta ahora.

Weber, prusiano de nacimiento, desmenuzó los principios elementales de la burocracia, desde su perspectiva de historiador y sociólogo. Sus seis principios elementales, bajo los cuales opera la burocracia moderna, (Weber, s/a, 3-9) nos permiten mostrar que la estructura funcional del Sistema Educativo Bolivariano es profundamente burocrática.

Existe todo un cuerpo de leyes que regulan y norman el sistema educativo. Dicho cuerpo establece una serie de jerarquías de cargos y niveles de autoridad fácilmente observables en la estructura de cualquier institución educativa.

Además de esto, el gigantesco cuerpo de personal administrativo, se especializa en cuidar y alimentar los archivos del sistema. Lo único que a nuestro juicio realizan de manera adicional al tercer principio de Weber, sería la extracción de esos archivos de información pertinente para los usuarios que la soliciten. Y estas son prácticamente sus únicas funciones.

En los principios cuarto, quinto y sexto, están descritas todas las funciones administrativas de los docentes. Las cuales en la práctica, ocupan una gran cantidad de tiempo y no pocos veces, es casi lo único a lo que están laboralmente obligados.

Por lo tanto, desde esta breve mirada a los principios de operatividad de la burocracia, podemos concluir que nuestro sistema educativo es fiel reflejo de la construcción prusiana más esparcida por el mundo occidental, la burocracia.

Pero Weber no se conformó con describir el sistema burocrático. En una segunda parte de su trabajo, observó la situación del funcionario dentro de este sistema y allí encontramos más elementos que nos ratifican de manera contundente la conclusión anterior.

Weber describe a continuación, las consecuencias del sistema burocrático sobre el funcionario, (s/a, 10-20). Paralelamente comentaremos las actividades de los funcionarios del Sistema Educativo Bolivariano que se igualan al pensamiento weberiano.

“I. La ocupación de un cargo es una «profesión»… El acceso a un cargo, incluidos los de la economía privada, se considera como la aceptación de un deber particular de fidelidad a la administración, a cambio de una existencia segura.” Por norma sólo los profesionales de la educación pueden ejercer dentro de un aula de clases, el ingreso de otros profesionales es la excepción de la norma.

Adicionalmente a esto y sobre todo durante la administración del sistema por parte de los partidos de la derecha, se exigía una fidelidad al partido que te daba el cargo. Aunque de manera diferente, la fidelidad a la Revolución, pudiese ser interpretada como la nueva manera de tener una “existencia segura” dentro del sistema burocrático.

Continua Weber con esta primera consecuencia asegurando “Por lo general, la posesión de certificados de estudios está vinculada a la calificación para el rango; y estos certificados, naturalmente, hacen resaltar el «elemento de status» dentro del rango social del funcionario”. Es decir mientras más cursos, diplomas y credenciales coloque en mi expediente, mejor calificado estará un docente, muy pocas cosas han cambiado en el Sistema Educativo Bolivariano.

En la segunda consecuencia del sistema burocrático sobre el funcionario y su vida personal, podemos observar la división clásica que hace la clase dominante capitalista sobre el actuar administrativo del funcionario y sus acciones políticas.

Observamos al leerla, que para Weber el burócrata es nombrado siempre por una jerarquía superior. Obviando que este nombramiento, traerá consecuencias sobre el accionar político del burócrata. Al afirmar que los funcionarios electos no son unos burócratas, en el sentido estricto del término, separa lo administrativo de lo político, un axioma que según Holloway “es parte integral del cambio en la forma de explotación” (1982, 28)

El sistema le pide al docente que no enseñe política partidista alguna, pero obvia que su nombramiento y estabilidad en las aulas es una política de estado sobre la cual el mismo docente tendrá una opinión que compartir o acciones concretas que tomar. El sistema reprime la expresión política del docente al convertirlo en un eunuco político ante sus estudiantes.

Esta separación de conceptos, impide ver al docente que su accionar pedagógico es altamente influido por la política del sistema, puesto que el docente creyendo que su cargo no es político, actuará de forma “apolítica” dentro del aula y le parece normal que el Estado regule dicha actuación. Esta es a nuestro juicio una de las formas que utiliza el sistema burocrático, para impedir una educación liberadora, personalizada e integral para con las nuevas generaciones.

La quinta y última consecuencia esbozada por Weber, nos permitirá reforzar lo anteriormente dicho: “5. El funcionario tiene la expectativa de realizar una carrera dentro del orden jerárquico del servicio público.” Esta misma expectativa es la que hace que se busque crecer en certificaciones pero no en conocimientos aplicados. Un curso de formación no se hace, para acrecentar la posibilidad de ser mejor docente, mejor persona, no se hace si tiene el número de horas mínimo que el baremo de clasificación exige para ser tomado en cuenta en los puntos, para ascender.

Es por esto que afirmamos que el sistema burocrático se hizo vida de manera muy especial en el sistema educativo venezolano. Lo que ha permitido, ver pasar una buena cantidad de reformas educativas, que no han cambiado en casi nada, la raíz burocrática de nuestra educación.

-

La perspectiva política

Un abordaje a este problema pudiera ser el confrontar con la realidad los fines que ha perseguido el sistema educativo venezolano en los últimos cincuenta años.

Para esto nos valdremos de las últimas dos leyes de educación que durante más o menos este tiempo, han descrito los fines que ha perseguido la educación venezolana. La ley de 1980 en su artículo tres señala entre los fines de la educación “el logro de un hombre sano, culto, crítico y apto para convivir en una sociedad democrática, justa y libre.”

Dejando de lado el problema de género de la redacción del artículo y el machismo no tan velado detrás del mismo, se puede afirmar que el sistema educativo venezolano tuvo como fin, en esta derogada ley, el formar ciudadanos para vivir en una sociedad democrática. (Nuestro es el resaltado)

De igual forma, aunque con un estilo menos machista en su redacción, la vigente Ley de 2009, en su artículo quince coloca como primer fin de la educación: “Desarrollar el potencial creativo de cada ser humano para el pleno ejercicio de su personalidad y ciudadanía, en una sociedad democrática”. (Igualmente nuestro es el resaltado)

Concluimos entonces que, desde hace mas de treinta años, el Estado venezolano ha tenido como primer fin de la educación el formar ciudadanos para vivir en democracia. Pero ¿qué es ciudadanía y qué democracia?

Por lógica del antónimo definiremos el concepto democracia que manejaremos en el presente trabajo. “Autocracia es auto investidura, es proclamarse jefe uno mismo, o bien ser jefe por principio hereditario. Mientras que el principio democrático es precisamente que nadie puede autoproclamarse jefe, y que nadie puede heredar el poder (Sartori, 2009, 56). Por lo tanto democracia es la “no autocracia”, como el mismo autor llega a definirla de forma más o menos sencilla.

Es decir que la finalidad del Estado venezolano ha sido formar un ciudadano para que ninguno de ellos pueda autoproclamarse Presidente(a) de la República o Diputado(a) de la Asamblea o Magistrado(a) del Tribunal Supremo o Rector(a) del Poder Electoral o Contralor Nacional, que serían los cargos representativos de los cinco poderes públicos de la sociedad venezolana, establecidos en la Constitución de 1999.

A estos cargos de ejercicio del Poder Público, se accede por elección directa o indirecta y no por autoproclamación o herencia, educar a nuestros niños para esto es y ha sido en los últimos treinta años, uno de los primeros fines del sistema educativo venezolano. Pero el poder ¿para qué?

No debemos olvidar que la democracia es una forma histórica y elegante mediante la cual, la humanidad sustituyó las luchas a muerte por la obtención del poder. Obtenido este poder, de forma democrática se supone, servirá para decidir ¿cómo se van a administrar los bienes del Estado? Que en la práctica corresponde a la simple elección de un equipo llamado gobierno, quien ejercerá ese poder delegado para decidir a cuáles políticas se les va a dar prioridad.

Por lo que nuestros estudiantes crecieron estos años formándose para respetar los resultados electorales (no autoproclamarse) y dejar que otros se proclamen autoridades del Estado y administren, sin nuestra opinión, los bienes que, en teoría, me han enseñado también, son de todos nosotros.

La manera concreta en que el sistema educativo arraigó en las generaciones del siglo xx esta aceptación del status quo pareciera ser que tiene que ver con el concepto de ciudadanía, el cual “en apariencia, … es un concepto igualitario, progresista, democrático, que afirma nuestra igualdad básica frente al estado, sean cuales sean las diferencias sociales” (Holloway, 1982, 26)

En realidad este concepto de ciudadanía, está basado en “una abstracción de las relaciones de producción, es decir,” separa lo político de lo económico. (Holloway, 1982, 28). De tal manera que, al establecer la igualdad en lo político, este concepto olvida la igualdad económica, una realidad que obliga a los más pobres a vender su fuerza de trabajo para subsistir y seguir siendo explotados.

Aunque el planteamiento de Holloway no es para la educación, pudiésemos preguntarnos: ¿Cómo podemos sentir que somos iguales, los estudiantes de una escuela estatal ubicada en la periferia de una ciudad a los estudiantes de una escuela privada de la zona más rica de esa misma ciudad? Y sin embargo, el sistema no respondió a esa pregunta, sino que por el contrario, formó al estudiante de ambas escuelas para aceptar esta diferencia económica como normal.

Interesa entonces descubrir las relaciones de dominación que se establecen en las prácticas educativas que se desarrollan dentro de los centros educativos del sistema. Interesa mucho desentrañar la relación del gigante del salón, que todo lo dice, todo lo escribe y todo lo dirige, con los enanos que desde abajo se acostumbran a crecer creyendo que todos somos “ciudadanos”.

Interesa buscar otra manera de enseñar que no somos iguales en lo económico, porque ha habido y hay una apropiación de los medios de producción por parte de una minoría que ha detentado además de ese poder económico, el poder político.

Para la proxima entrega, se abordaran la perspectiva histórica y la de los modelos de desarrollo.

Bibliografía citada.

-

Asamblea Nacional de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela (2009) Gaceta Oficial Extraordinaria N° 5929 del 15 de agosto. Caracas. Venezuela.

-

Brito Figueroa, Federico. Historia económica y social de Venezuela, una estructura para su estudio. Tomo II. Ediciones de la biblioteca de la UCV Caracas. 1972. Octava edición 2009.

-

Congreso de la República de Venezuela. (1980) Gaceta oficial N° 2.635 de fecha 28 de julio de 1980. Caracas. Venezuela.

-

Declaración de Río de Janeiro. Repensar la Teoría del Desarrollo. En publicación: Cuadernos del Pensamiento Crítico . Latinoamericano no. 4. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales. Enero 2008.

-

Easterly William, En busca del Crecimiento. Andanzas y tribulaciones de los economistas del Desarrollo. Antoni Bosch Editor. Barcelona. 2003.

-

Escobar Arturo, 2007. La invención del Tercer mundo. Construcción y deconstrucción del desarrollo. Editorial El perro y la Rana. Caracas , Páginas 20-30.

-

Furtado, Celso. Los desafíos de la nueva generación. En publicación: Cuadernos del Pensamiento Crítico Latinoamericano no. 4. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales. Enero 2008.

-

Gil Pérez, Daniel y de Guzmán Ozámiz, Miguel. La enseñanza de las ciencias y la matemática. Tendencias e Innovaciones. Editorial Popular, Madrid, 2001.

-

HINKELAMMERT, FRANZ. Pensamiento crítico y crítica de la razón mítica Theologica Xaveriana [en línea] 2007, 57 (Julio-Septiembre): [fecha de consulta: 27 de enero de 2013] Disponible en: <http://www.redalyc.org/src/inicio/ArtPdfRed.jsp?iCve=191017478003> ISSN 0120-3649.

-

Holloway, John. Fundamentos teóricos para una crítica marxista de la administración pública. Ediciones INAP, Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública, México, 1982, consultado en http://es.scribd.com/doc/99445496/Holloway-Fundamentos-teoricos-para-una-critica-marxista-de-la-administracion-publica.

-

Marx, Karl. El Capital, Tomo I. En http://es.groups.yahoo.com/group/VOZ_Rebelde/ .

-

Ornelas Delgado Jaime, 2011. Volver al Desarrollo. Revista Problemas del Desarrollo. Enero-marzo 2012. Número 168.

-

Ponce Aníbal. “Educación y lucha de clases”. Editado digitalmente por Partido Comunista Español, consultado en: http://es.scribd.com/doc/13904629/Anibal-Ponce-Educacion-y-lucha-de-clases-libro-completo.

-

Quintar Estela, (2004) Colonialidad del pensar y bloqueo histórico en America Latina. En Amèrica Latina: los desafíos del pensamiento crítico, Sánchez Ramos y Sosa Elízaga, coordinadoras. Páginas 180-204, Siglo XXI editores. México.

-

Rousseau, Juan Jacobo. El Contrato Social o principios del Derecho Político. ElAleph.com. 1999. Descargado en www.elaleph.co,.

-

Sartori Giovanni (2009) “La democracia en 30 lecciones” Distribuidora y Editora Aguilar, Altea, Taurus, Alfaguara S. A. Bogotá. Colombia.

-

Weber, Max. (s/a) “¿Qué es la burocracia?”. Ediciones Elaleph.com. En www.elaleph.com. Año 2000

Fuente del artículo:

Fuente de la imagen: http://caiohostilio.com/wp-content/uploads/science-and-ideology.png

Users Today : 258

Users Today : 258 Total Users : 35459853

Total Users : 35459853 Views Today : 432

Views Today : 432 Total views : 3418404

Total views : 3418404