Liberia/Abril de 2017/Fuente: Financial Times

Resumen: En gran parte de África, la educación está en crisis. Eso es en parte porque se ha estado expandiendo tan rápido. Entre 1990 y 2012, la matriculación en la escuela primaria en todo el continente se duplicó a 149m, según un informe de la Unesco de 2015. Desde 2000, los gobiernos de al menos 15 países africanos han abolido las tasas escolares. Esto ha creado una demanda masiva de lugares. De los 58 millones de niños de primaria que no asisten a la escuela en todo el mundo, 38 millones están en África. En África subsahariana, la mayoría de los sistemas escolares están terriblemente subfinanciados. En un continente cuya población en globo es a menudo promocionado como un motor de la prosperidad, las generaciones están creciendo incapaces de tomar su lugar en una fuerza de trabajo moderna. Si algo puede ayudar a África a cumplir la promesa que muchos ahora vislumbra en sus ciudades bulliciosas y en países que se han beneficiado de años de crecimiento decente, paz relativa y liderazgo marginalmente mejorado, es la educación. En su mayor parte, no está sucediendo.

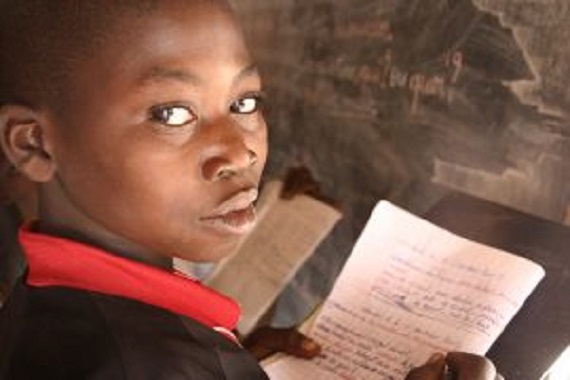

The children were doing tests in the government school in the town of Smell No Taste. The soupy air was thick with sweat and diesel. An occasional black wasp, menacing but silent, skimmed in and out of the unlit classrooms. The place had officially been rebranded Unification Town. But everyone knew it by its old name of Smell No Taste from when American GIs had cooked on a nearby base, sending the aroma of unaffordable meat wafting over the tumbledown shacks.

We’d driven an hour or so from the centre of Monrovia, the grimy, energetic Liberian capital, to the Robert Stanley Caulfield Elementary and Senior High School, which was set off the highway at the end of a dirt track. In the dusty red courtyard was a pole with the red-white-and-blue Liberian flag, designed by the freed American slaves who had, in 1847, declared Liberia Africa’s first independent republic. The education ministry had supposedly called ahead but the headmaster, who wore a far-off look, showed no signs of expecting me. The school had 1,200 students and ran two half-day shifts between 8am and 6.15pm. Even so, the children were crammed into classrooms, sitting on broken-down desks, with a few spillover pupils seated in the open-air corridor. There were 38 teachers. All were paid regularly, a minor miracle in a country where unpaid volunteers make up teacher shortfalls in many schools.

The librarian, 65-year-old James Toe, brought out a laminated sheet marked “laboratory equipments”, with pictures of test tubes, microscopes and safety glasses. The children used the drawings in lieu of actual objects. Music lessons were conducted on the same basis. “We don’t have any of this. We don’t have nothing,” Toe said, speaking in the English dialect used throughout Liberia. “We want to extend the shelves,” he added, as though this might magically produce new books. The wall was mostly covered with slogans. One read: “Education is the only husband and wife that cannot divorce you.” Across much of Africa, education is in crisis. That is partly because it has been expanding so fast. Between 1990 and 2012, primary school enrolment across the continent more than doubled to 149m, according to a 2015 Unesco report. Since 2000, governments in at least 15 African countries have abolished school fees. This has created massive demand for places.

Of 58m primary-aged children not attending school globally, 38m are in Africa. In sub-Saharan Africa, most school systems are appallingly underfunded. In a continent whose ballooning population is often touted as a driver of prosperity, generations are growing up incapable of taking their place in a modern workforce. If anything can help Africa fulfil the promise that many now glimpse in its bustling cities and in countries that have benefited from years of decent growth, relative peace and marginally improved leadership, it is education. For the most part, it is not happening. A study published by the World Bank this year of primary schools in seven sub-Saharan countries — Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, Tanzania, Togo and Uganda, comprising 40 per cent of the region’s population — found that, on average, students receive less than three hours’ tuition a day and that many teachers fail simple literacy and numeracy tests. Another study, by Justin Sandefur, senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, compared maths scores across countries. He found that the median child in an African classroom scored below the fifth percentile of wealthy countries. Teacher Matthew G Luo uses a tablet during his English class at Martha Tubman Elementary School © Jane Hahn Liberia is an outlier. It does worse. According to the country’s education ministry, fewer than 60 per cent of school-age children are actually in school. Attendance may not be worth the effort. Adult women who have reached fifth grade stand only a 20 per cent chance of being able to read a single sentence. In 2013, some 25,000 high-school graduates took the entrance exam for the University of Liberia. No one passed. Part of the reason is that Liberia is still recovering from a gruesome civil war, which raged for much of the 1990s and ended only in 2003. Toe, the librarian, remembers gangs of rebel soldiers ransacking schools, many of which closed for years. “Everybody left. If you were here, they kill you,” he said. “We all went to the rural areas and hid.” More recently, in 2014, as Liberia was staggering from its knees, it was struck by Ebola. Many parents kept their children out of school, worried the disease would “grab them”.

George Werner was appointed education minister in 2015 with a rescue mission. A former teacher and self-described “system-preneur”, he did not have much to work with. The budget for Liberia’s 900,000 or so schoolchildren was $44m, of which $38m went on teacher salaries. Werner took drastic action. In January 2016, he announced that he was outsourcing 50 schools to Bridge International Academies, a US-based for-profit provider of low-cost education that was already teaching 100,000 children in schools in Kenya, Nigeria, Uganda and India. If successful, many, or even all, of Liberia’s schools could be outsourced to the same company. Other African countries were watching. The Mail & Guardian newspaper in South Africa captured the continent-wide controversy with its excitable headline: “An Africa First! Liberia Outsources Entire Education System to a Private American Firm. Why All Should Pay Attention.”

Bridge is sometimes referred to as the Uber of education. It is backed by a who’s who of US investors, including Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg and Pierre Omidyar, the founder of eBay. It has also attracted investments from venture capital funds, including Learn Capital and Novastar, as well as from the US and UK governments and the investment arm of the World Bank. With well over $100m in capital, it has rapidly expanded to become one of the largest providers of low-cost private education in the world. Werner had visited Bridge in Uganda and Kenya, where it had opened its first school in 2009 and charged less than $7 a month per child. He was an instant convert. The Bridge model used technology, standardisation and rigorous monitoring — none of which were much in evidence in Liberia. Teachers read word-for-word from a scripted lesson plan displayed on cheap tablets and devised in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Werner was struck by teachers’ enthusiasm and the fact that children appeared to be reading and writing. A teacher uses a tablet to check a student’s work at Upper Careysburg school, Careysburg © Jane Hahn Bridge’s co-founder Shannon May, an anthropologist and Harvard graduate now based at the company’s headquarters in Nairobi, convinced him that she could provide similar quality lessons within Liberia’s meagre budget. There was, however, a hitch. When word of Werner’s plan got out, there was an instant backlash.

Perhaps because of the scale of its ambition and its slick American feel, Bridge had rubbed many educators up the wrong way. Some objected to the use of tablets and scripted lessons, which, they said, reduced interaction between teacher and pupil and smacked of the utilitarianism of Jeremy Bentham, the 18th-century British philosopher who once designed a prison that could be guarded by a single watchman. “It is almost institutionalising rote learning,” said David Archer, an education expert at the charity ActionAid and one of Bridge’s most tenacious critics. “In a way, it’s a very Victorian model. What appears to be high-tech and modern actually creates a teaching and learning practice that takes us back 100 years.” Archer and others objected to something else: the idea of profiting from some of the poorest parents in the world. In the case of Liberia, where the government was paying, Kishore Singh, the UN special rapporteur on the right to education, said Werner’s plan violated Liberia’s legal and moral obligation to provide schooling. “Education is an essential public service and, instead of supporting business in education, governments should increase the money they spend on public educational services to make them better,” he said.

When I caught up with Werner on the balcony of the Mamba Point Hotel in Monrovia, the grey waves of the Atlantic tumbling into the shore behind him, he defended the profit motive. “In every country I know, public and private sectors are side by side,” he said. “We do that for roads and bridges. Why not for education?” Yet so intense was the controversy that Werner backtracked. He engaged international advisers, including Ark, an education charity that runs UK academy schools and supports developing country governments in education. Together they devised a pilot scheme to quell the critics. Officially known as Partnership Schools for Liberia, several competing operators would manage schools in partnership with the state.

Results would be measured in a randomised, controlled trial. Bridge had little choice but to accept the new set-up. It would run 25 schools, a far cry from the 50 originally offered. It signed a memorandum of understanding that gave it first dibs on schools and flexibility to hire and fire teachers. Because its model relied on technology, which enabled it to deliver lesson plans and check on teachers’ attendance and performance, it needed schools served by 2G telecoms networks. It also demanded sites near main roads — to cut down on transport costs — and with classrooms in reasonable condition. Students work out maths problems on a chalk board at Kenlay school, run by Omega © Jane Hahn Seven other operators emerged from a competitive bidding process to win the chance to manage 70 additional schools. Liberia’s education ministry pays the teachers. Ark provides an annual subsidy of $50 per child to each of the seven operators that publicly tendered. Bridge has found its own funds, presenting a budget that suggests it will spend $8.9m. That is roughly $1,100 per child — far more than other operators, though Bridge says it is mostly one-off start-up costs. The new schools opened in September. The evaluator did baseline tests of children in both partnership and control schools. The race was on to see whether partner-managed schools could improve learning. Inevitably, each operator wanted to show it could do better than the rest.

And so it was that this month I flew to Liberia to see things for myself. I had gone to Smell No Taste to get an idea of a typical government school. I visited a few other state schools along the way, including one where lessons were suspended every Thursday so that children, machetes in hand, could work in the nearby fields. My main aim, though, was to see partnership schools to discover whether third-party operators could make a difference. In all, I visited schools managed by four independent operators: Rising Academy, which runs low-cost private schools in Sierra Leone; Omega, a chain of for-profit schools based in Ghana; and BRAC, a large Bangladeshi non-governmental organisation. And then, of course, there was Bridge. The first Bridge school I visit in Liberia is the Martha Tubman Elementary School, in Nimba, several hours outside Monrovia along a main road. The month before, in Kenya, I saw a Bridge school in a Nairobi slum. Save for different-coloured uniforms — mandated by the Liberian government — Bridge has pretty much replicated the Kenyan model here, several thousand miles away in rural Liberia.

Classrooms are basic but functional. Pupils wear chequered blue uniforms, manufactured in India, and emblazoned with the Bridge logo. Kids have textbooks. And the teachers have their tablets. In Class 5B, a teacher, dressed in a yellow- and red-flowered shirt, paces the floor, reading from his device. “Don’t add, don’t subtract,” several teachers tell me later, meaning they should not divert one iota from the tablet’s script. Bold text on the screen is for the teacher to say out loud: “Pens down. Eyes on me. Now we will do our board activity.” The light text says things such as “Scan”, meaning the teacher should make eye contact with pupils, or “Signal”, meaning teachers should snap their fingers. Students at Deemie school take time off school in order to work © Jane Hahn As with Bridge Kenya, there is a “character board” with various encouragements and admonitions relating to behaviour. Names are written in chalk besides designations such as “cleanliness captain” or “back line captain”. On the main board is a list of rules: “No stealing. No fighting in class. No sleeping in class. Respect others’ view.” Bridge teachers punctuate lessons with chants. In Liberia, they use the acronym “Star”. The kids in 5B call out, with varying degrees of enthusiasm: Sit tall Track the speaker with your eyes and body Ask and answer questions Reach for the stars! The last line is accompanied by fists punched in the air. I’m met at the school by a cluster of Bridge employees, including a public relations director, a community engagement director, and Josh Nathan, the 28-year-old academic director for Liberia. Nathan, a Bostonian, wears dark sunglasses (even in class) and a pink-chequered shirt, like a picnic cloth. I encounter him at three different Bridge schools and each time he greets me with an outstretched hand. He oozes friendliness. “Everybody we’re employing is a real body in a real classroom,” he says, highlighting one of Bridge’s selling points over state-run schools, where teachers often go awol. Nathan is keen to dispel the idea that Bridge is about rote learning. Quite the contrary.

Typical government schools are all “chalk and talk”, with the teacher doing 90 per cent of the talking. “We want to get the kids doing the hard work,” he says. Bridge lesson plans allow the teacher to explain a principle, for the class to solve a problem together and then for pupils to try problem-solving themselves. Parents seem generally happy with the Bridge experience. “This is the modern time,” says Joseph Flomo, a 42-year-old father of two, referring to the use of tablets. Education is important, he says. He learnt maths at school and, as a result, landed a job as a meter reader at a Liberian electricity company. Students at Kenlay school run by Omega, a chain of for-profit schools © Jane Hahn By phone I speak to Shannon May, Bridge’s co-founder. She rejects a common criticism that reliance on scripted lessons might raise the floor on teaching standards but lower the ceiling. “I would suggest you follow the evidence,” she says. “Bridge doesn’t have an ideological stand on pedagogy, but practical solutions, not just for one classroom but for thousands of teachers and hundreds of thousands of students.” She quotes studies showing that Bridge students make gains of around 0.4 standard deviations in learning. Results will be even better in Liberia, she predicts. “If it didn’t work, we wouldn’t do it.” Critics say Bridge’s numbers have not been independently verified. They also say Bridge is not comparing like with like. In Kenya, the parents of Bridge children — who can afford to pay the $7 monthly fee — are, by definition, slightly better off and more committed to education. May attributes criticism to vested interests, including labour unions, embarrassed civil servants and educational experts. “That kind of engineering approach, deconstruct-it-and-rebuild-it approach, bothers folks who are married to what’s gone before,” she says. “There is always someone who loses when things change. But our focus is how can kids win.” Back in the Bridge classroom, the teacher is trying to bring the lesson to life. But even a sympathetic observer can’t help noticing that he spends more time staring at the tablet than at the children. At one point he copies a sentence from screen to board. “A human heat made of muscle tissue,” he chalks. The word “heat” sits there, the mistake apparently unnoticed by either teacher or pupils.

Bridge has arranged for a couple of teachers to talk. Alexander Zouropeawon is 28. Bridge, he says, is all about transformation. “To transform the youngsters into successful, resourceful ones,” he says. “Learning is dynamic, not static. I have a growth mindset. Bridge methodology is better because it has the ability to keep the children focused on their objective.” Is he paid regularly? The ministry has made progress in flushing the payroll of dead or non-existent “ghost teachers”. Some 1,500 have been erased, saving $3.8m a year. The system has, however, coped less well with getting new teachers on payroll. Bridge has fired those who didn’t meet its minimum requirements and hired new ones to replace them. Not all have been paid. That includes Zouropeawon, who later takes me aside to explain that four teachers at the school are not receiving their salaries. This week’s FT Weekend Magazine cover Another teacher, not introduced by Bridge, likes the smaller classroom sizes, which are a stipulation of the partnership agreement. Though he is an experienced teacher, he has adapted to the tablets. “I enjoy the teaching plan they send over to us. We sync it in the morning,” he says, referring to the principal’s “master phone” on which regularly updated lessons are downloaded from Boston and Monrovia. He does worry, though, that if the teachers don’t understand the lesson, the students will catch on and lose respect. He also resents the longer hours. “I’m here from 7am and leave at 4pm. I’m not eating anything,” he says, mentioning the absence of a “feeding programme” — a school lunch — for either teachers or students. His pay has remained the same, at about $115 a month. “I’m a human being,” he says. “If things continue like this, I will not stay.”

Obvious teething problems aside, the Bridge school is slicker than two others I visit, one operated by BRAC and the other by Omega. To be fair, both of those schools are in more remote areas in poorer communities, beyond the reach of a paved road, let alone 2G. The BRAC school is a good seven hours’ drive from Monrovia. In the rainy season it might take double that. The cost of reaching it in petrol alone is no small consideration for an operator seeking to push monitoring up and keep costs down. We set out in the evening on a Chinese-built tarmac road, speeding through the bush, which presses in on us in the darkness. After a few hours, the driver swerves, curses and screeches to a halt, before reversing. A silent crowd has gathered around the body of a dead child in the road. The only light is from their mobile phones. We press on. After an overnight stay in Gbarnga, the capital of Bong County and once the military base of Charles Taylor, the former president convicted for crimes against humanity, we drive for several more hours. The road slashes a mud-red path through the rainforest of Lofa County, which skirts the Guinea border. A student walks home from Passama school, operated by BRAC, an NGO, in Gbarnga, Bong County © Jane Hahn The headmaster of the Passama school is James Y Lavelagbo, a shy 39-year-old. He says BRAC has improved teaching standards through monitoring and workshops. The benefits are not obvious to the casual observer. One class has no teacher because she has gone home sick.

The kids, packed in tight rows, fidget in the darkness. Another class is in a similar state. In the corner sits a sullen teacher. “That’s not a lesson. It’s kids sitting in a room,” complains one ministry observer. Passama has no lunch programme either, a recurring problem for partnership and normal state schools alike. Whether because of poverty or neglect, many children don’t bring food. “When they have an empty stomach, they won’t listen,” says Gbolumah Kobor, a parent. Someone else quotes a saying about hunger. “An empty bag cannot stand.” A seven-hour drive back towards the border with Ivory Coast takes us to Kenlay school, run by Omega. Alain Guy Tanefo, Omega’s Cameroonian chief executive, is there to meet us. “This is extremely remote. Let’s be honest,” he says, peering into the jungle beyond. “For the pilot phase, we never thought we’d be so far out.” The remains of an old latrine block outside Passama school © Jane Hahn Like Bridge, Omega uses teacher computers, although lessons are less micromanaged.

Out here the technology is problematic. Many of the teachers’ devices — Omega uses Android phones rather than tablets — are blank. One or two are cracked. Some teachers, unfamiliar with smartphones, have accidentally erased the lesson app. Tanefo says Omega’s model is designed for less remote schools, preferably in clusters to reduce transport costs. Omega has a strict break-even policy and says it can run schools at scale within Liberia’s budget. Tanefo’s main criticism of Bridge is not that it seeks to make money — something he defends as a way of bringing rigour and accountability. Besides, Liberia’s schools will still be free to parents. Instead, he says, Bridge’s model is too expensive. That, he says, is largely because of the high costs incurred by its Massachusetts office, which he contrasts with Omega’s in Ghana. Globally, Bridge admits to losing $1m a month last year, although it says this is in line with its business plan. It is an irony that a company sometimes criticised for seeking profit is actually making a loss. “I don’t believe they will ever break even,” Tanefo says. “Eventually, they will have an IPO and create goodwill but I don’t believe they will ever be able to cover their costs.” Bridge rejects this, saying that its US office is less expensive than people think. As it moves to scale — it aims to have 10 million students by 2025 — it will, it says, radically cut costs per child as the benefits of standardisation kick in. My last-but-one stop, the Cecelia A Dunbar school in Freeman Reserve, close to Monrovia, is run by Rising Academy, which started out in neighbouring Sierra Leone and now runs five Liberian partnership schools.

Perhaps I arrive on a good day but, for my money, it is the best of the lot. Though the classrooms are shabby and some children have no desks, the pupils seem thoroughly engaged. There are no tablets, but teachers appear to have well-structured lesson plans. Students are up at the board, working in groups or writing intently. Teachers lavish praise. “We want them to interact with students, not with the tablet,” says Christina PioCosta-Lahue, Rising Academy’s managing director. Christina PioCosta-Lahue (centre) of Rising Academy at the Cecilia A Dunbar school in Freeman Reserve © Jane Hahn When I meet Werner, the education minister, he admits there have been teething problems. But he is generally pleased with how things are going. Learning outcomes are improving, he believes, although results of the external assessment are not yet in. Still, he is minded to expand the scheme, perhaps dramatically, from the next academic year.

On one level this sounds good. Liberia has recognised the profound deficiencies of its education system and is trying to do something about it. Doubtless it has much to learn from outside experts. But handing over a chunk of its education system to private providers is a drastic step, particularly if they intend to squeeze a profit from the ministry’s tiny budget. “Some form of public-private partnership might be part of the puzzle here but you need good governance around that, proper public procurement and monitoring,” says Sandefur, who is overseeing the randomised trial. “What’s missing is government capacity to hold up its end of the bargain and, in lieu of that, you’ve got some operators willing and able to run roughshod.” Sandefur also worries about whether Bridge and others can make their economic model work. It is all very well for a Silicon Valley start-up working on a jazzy new app to raise millions only to go bankrupt. But what would happen if school operators could not work out how to break even in Liberia? “Will they stick with those schools or will they cut their losses if things are not working out?” he asks. My final school is in Careysburg, just outside Monrovia. It is run by Bridge. By now the set-up is familiar. Same classrooms. Same uniforms. Same tablets. Some teachers work skilfully with the device. You might even forget it is there. Others struggle to take their eyes from the screen.

One teacher in Careysburg is like that. “Our. Goal. Is. To. Revise. For. The. Marking. Period. Test,” he intones. “Great. Great,” he says, when the children answer a question, correctly or otherwise. The school’s headmaster is 51-year-old Martin Flomo. I spend some time in his office talking to parents and am just about to leave when I notice his slightly crestfallen face. I have neglected to ask him what he thinks. What is the school like under Bridge? “I like the changes. There’s a great difference,” he replies. Then he reaches for a piece of paper covered in his looping red script. At the top are the words “A great difference.” He reads down the page, explaining how the school has longer hours, better teaching and helpful tablets. “Don’t add,” he beams, looking up. “Don’t subtract.” David Pilling is the FT’s Africa editor Photographs by Jane Hahn The text has been amended to reflect the fact that Bridge was originally offered 50 schools in Liberia, that it devises lesson plans for Liberia both in the US and Monrovia and that its global headquarters are in Nairobi.

Fuente: https://www.ft.com/content/291b7fca-2487-11e7-a34a-538b4cb30025

Users Today : 7

Users Today : 7 Total Users : 35460216

Total Users : 35460216 Views Today : 10

Views Today : 10 Total views : 3418905

Total views : 3418905