The Indian Ocean seemed ready to hit Africa with a one-two punch. It was September 2019, and the waters off the Horn of Africa were ominously hot. Every few years, natural swings in the ocean can lead to such a warming, drastically altering weather on land—and setting the stage for flooding rains in East Africa. But at the same time, a second ocean shift was brewing. An unusually cold pool of water threatened to park itself south of Madagascar, leading to equally extreme, but opposite, weather farther south on the continent: drought.

Half a world away, at the Climate Hazards Center (CHC) of the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), researchers took notice. Climate models, fed by the shifting ocean data, pointed to a troubling conclusion: By year’s end, that cold pool would suppress evaporation that would otherwise fuel rains across southern Africa. If the prediction held, rains would fizzle across southern Madagascar, Zambia, and Mozambique at the beginning of the growing season in January, the hungriest time of year. Zimbabwe, already crippled by inflation and food shortages, seemed particularly at risk. “We were looking at a really bad drought,” says Chris Funk, a CHC climate scientist. It was a warning of famine.

The CHC team, led by Funk and geographer Greg Husak, practice what they call “humanitarian earth system science.” Working with partners funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), they have refined their forecasts over 20 years from basic weather monitoring to a sophisticated fusion of climate science, agronomy, and economics that can warn of drought and subsequent famines months before they arise. Their tools feed into planning at aid agencies around the world, including USAID, where they are the foundation of the agency’s Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), which guides the deployment of $4 billion in annual food aid. Increasingly, African governments are adopting the tools to forecast their own vulnerabilities. “They’ve been absolutely key” to improving the speed and accuracy of drought prediction, says Inbal Becker-Reshef, a geographer at the University of Maryland, College Park, who coordinates a monthly effort to compare drought warnings for nations at risk of famine. “Every single group we work with is using their data.”

The forecasts are needed more than ever. From 2015 to 2019, the global number of people at risk of famine rose 80% to some 85 million—more than the population of Germany. Wars in Yemen, Syria, and Sudan are the biggest driver of the spike. Global warming, and the droughts and storms it encourages, also plays a role. The pace and severity of storms and droughts in Africa seem to be increasing, Funk says. “Both extremes are going to get more intense.”

The consequences of drought can be catastrophic, but it is hard to detect. Unlike temperature, rainfall is spotty and local, heavily influenced by terrain. Three important clues that drought is coming—low accumulated rainfall, a lack of soil moisture, and high air temperatures—are difficult to measure from space. Satellites can see when green fields turn brown, but that often comes too late to inform a large-scale aid response. In Africa, researchers cannot rely on data from ground stations, either. Zimbabwe, for example, only has a few weather stations, and sometimes those don’t even measure rainfall. This “reporting crisis” is pervasive across the continent; over the past 30 years, the number of stations with usable public data has dropped by 80% to only 600 or so.

Forecasting drought months into the future is even harder. Weather forecasts stretch out only a few weeks. Moving beyond that requires an understanding of large-scale climate patterns that influence weather over months or years. The banner example is the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, a pattern of winds and surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific Ocean that shifts every few years, altering global weather in myriad ways. Weather in Africa is influenced by other oscillations, including the two Indian Ocean shifts CHC was watching, known as the Indian Ocean Dipole and the Subtropical Indian Ocean Dipole. But the “teleconnections” between the ocean and distant weather patterns are poorly understood, and aid agencies can be leery of relying on them for long-term drought predictions. They want evidence from real-time monitoring that drought is on the way.

Double trouble

The growing season in southern Africa was still months away when CHC noticed the signs of trouble—plenty of time for it and its partners, including a team of food security analysts in Washington, D.C., to refine their predictions and validate them with local observations. The fieldwork would be led by Tamuka Magadzire, a CHC agroclimatologist based in Botswana whose analysis had shown that conditions in Zimbabwe were already ripe for famine: The previous harvest was weak, shriveled by the lowest rainfall since the early 1980s. The currency was essentially fictional, and the country’s poorest had to devote 85% of their income to food. On visits in the past few years, Magadzire brought along maize for his friends and family. “It’s just been really bad in terms of long dry spells,” he says.

A perfect storm was looming. Through the fall of 2019, Funk and his colleagues at FEWS NET sent a series of escalating warnings to senior officials at USAID. No one wanted to repeat what had happened a decade earlier, elsewhere in Africa. The group’s forecasting record lent credibility to their warnings. But whether their call would be heeded this time would also depend on the strength of the evidence for an impending drought, political will in the United States and elsewhere—and a pandemic that had yet to rear its head.

CHC BEGAN with a dream. In 1995, Funk was a smart but directionless consultant working in Chicago for the credit card company Discover; he mined databases of personal information to identify consumers to target with ads. “It was, basically, working for the dark side,” he says. In the dream, he was standing with friends in Lake Michigan, smoking and drinking beer, when he felt the lake tug on his legs. Turning, he saw a tidal wave coming to inundate the city. But his first impulse was to rush to the office and buy stock options. “This dream really freaked me out,” he says. “What kind of person sees the city is going to be destroyed and wants to sell options?” Funk, from an Indiana farm town, recalled how struck he was as a child by Live Aid, the 1985 charity concert for Ethiopia. He needed to make a change. He wanted to make a difference. He quit.

Funk wound up studying geography at UCSB in a group that focused on statistical climatology. He met Husak, another geography graduate student, and James Verdin, a visiting remote-sensing scientist from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). The three of them witnessed the record El Niño of 1997–98, in which warm waters from the western Pacific sloshed eastward toward Peru, triggering long-range atmospheric shifts that brought punishing rains to their California campus. El Niños also seemed to suppress rains in southern Africa, so Verdin, who now heads FEWS NET, worked with Funk to see whether greenness measures of maize fell in southern Africa during the 1997–98 event. “It was kind of mixed results,” Verdin says, “but we got it published.”

Verdin encouraged FEWS NET to sponsor Funk’s and Husak’s studies. By the time the next El Niño came, in 2002, the UCSB team had compiled scattered rainfall records dating back to 1961 to quantify how El Niño events dried up water resources across southern Africa. USAID used the resulting map and report to respond quickly after the 2002 El Niño, sending some $300 million in food aid. It was the first time the agency incorporated climate forecasts into its food aid, Funk says, and it relieved some of the ensuing famine. “And we’re still basically doing the same thing, better, smarter, faster.”

Funk went to work for USGS, but he remains affiliated with UCSB, where he serves as resident provocateur while Husak steers CHC’s growing staff. Funk’s churning mind keeps them busy, Husak says. “We lift up a lot of rocks and see what’s going on underneath them.”

Chris Funk found his calling with drought prediction at the Climate Hazards Center.

AMELIE FUNK

In the 2000s, one of those rocks led Funk back to Africa to study a different teleconnection. He and Alemu Asfaw Manni, a FEWS NET analyst in Ethiopia, gathered historical rainfall data across the country’s highlands, where the soil is fertile but rain so scarce that some crops need months to germinate. Most climate models showed East Africa would get wetter with climate change. But since the early 1990s, the team found, the highlands’ long rainy season had gone into a steep decline. “This was a holy moly moment,” Funk says. The trend, dubbed the “East African climate paradox,” has held true to this day.

The explanation seems to lie in the ocean. Weather records indicated that many droughts in East Africa seemed to strike during strong La Niñas, El Niño’s opposite number, when the western tropical Pacific heats up while the eastern Pacific cools. The UCSB team didn’t understand the connection, but by August 2010, another La Niña was brewing in the Pacific. FEWS NET warned that rains across the Horn of Africa, including Ethiopia and Somalia, would be late, weak, and erratic.

Politicians and donors largely ignored the alarm. La Niña’s threat was poorly understood, different aid groups were issuing disparate warnings, and a degree of crisis fatigue had set in about Somalia, which had been in turmoil for years. But over the next 9 months, the rains failed as predicted. Food prices tripled and malnutrition grew rampant.

In mid-2011, the United Nations finally declared a famine, and USAID ultimately delivered more than 300,000 tons of wheat, high-energy biscuits, and other staples. But the aid came too late and didn’t reach enough people. Within the next year, the famine killed 260,000 people in Somalia alone. Half of them were children under the age of 5. As a damning U.N. report later put it: “The suffering played out like a drama without witnesses.”

“It was really, really bad.” Verdin sits in his austere, modern USAID office in Washington, D.C., reflecting on the Somali crisis, now nearly a decade ago. There were extenuating circumstances. Al-Shabaab, the Islamist militant group, was ascendant, and humanitarian groups feared that if their aid ended up in the wrong hands, the U.S. government might have prosecuted them, he says.

The famine warnings had been accurate—but they had also seemed insufficient. The UCSB team “didn’t convey the information as effectively as we could,” Funk says. The loss of weather stations meant their rainfall measures were getting worse, and most satellite-based estimates lacked the detail to show how dry specific crop-growing regions were getting. And their explanation of why La Niña was a threat seemed far too abstract. “You’re asking somebody to open up their wallet and spend millions,” Funk says. “They’re not just going to do it because you say, ‘Our standardized precipitation forecast is −1.2.’”

THE FAMINE FORECASTERS needed better data. In 2015, those dreams came true when CHC released a tool called CHIRPS (which stands for Climate Hazards Center Infrared Precipitation with Station Data). It was the culmination of years of work compiling local rainfall records across Africa and folding in satellite data. Since the late 1970s, a coalition of European countries has maintained geostationary weather satellites over Europe and Africa. Among other things, the satellites measure the temperature of clouds by the infrared light they emit. When the temperature of clouds high in the atmosphere drops below −38°C, it is likely raining lower down. By using this record to fill in rainfall between ground stations, CHIRPS assembled a continentwide rain database stretching back to 1980.

CHIRPS not only provides the historical data for climate researchers to study teleconnections, but it also collects the contemporary data for near–real-time monitoring of rainfall. “It’s quite a step forward,” says Felix Rembold, a drought forecaster at the European Union’s Joint Research Centre. It’s also in constant development: Pete Peterson, the CHC coding guru who has spearheaded CHIRPS, often woos local agencies to fill gaps in station coverage. For example, Ethiopia shares data from 50 government stations with CHC—even though its agricultural and meteorological agencies won’t share their data with each other.

The data find their way back to Africa as CHC-affiliated field scientists train African agencies on using CHC products. For example, Kenya’s Regional Centre for Mapping of Resources for Development has begun to serve up CHIRPS data to help local users forecast rains. Ideally, Funk and company hope to slip into the background, as Magadzire and his peers weave the CHC tools into the fabric of African drought response. Magadzire has had lucrative job offers, but the challenge is too compelling, he says. “My heart is in the improvement of conditions in Africa.”

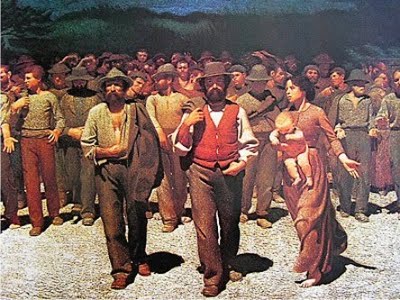

Zimbabwe, crippled by inflation and weak harvests, needed food aid in 2019. This year could be far worse.

GUILLEM SARTORIO/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

The long-term rainfall history in CHIRPS has enabled CHC researchers to refine their understanding of the La Niña teleconnection. By comparing global weather records and the predictions of climate models to the CHIRPS records, they have discovered the importance of the “western V,” an arc of hot Pacific water that can appear during a La Niña event. Shaped like a less-than sign, it angles from Indonesia northeast toward Hawaii and southeast toward the Pitcairn Islands, and it forms as La Niña pens warm waters in the western Pacific.

It has far-reaching consequences. As water temperatures spike, energetic evaporation saturates low-level winds flowing west from the cool eastern Pacific. The moist winds dump their water over Indonesia—the wet get wetter. The winds, now high and dry, continue their march west across the Indian Ocean and drop down over East Africa, preventing the intrusion of nearby moist ocean air and breaking up rain clouds. Global warming is strengthening these effects, causing them to linger even after a La Niña fades. And it appears that because of the ongoing ocean warming, they can happen without a La Niña at all, Funk says.

Armed with this new understanding, Funk in May 2016 found himself at USAID headquarters. A strong El Niño had just waned, and sea surface temperature trends suggested La Niña would follow. If it did form, he warned, FEWS NET’s food analysts should prepare for sequential droughts in East Africa. A set of new seasonal climate forecasts from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration echoed Funk’s drought warnings. CHIRPS revealed that the October-December rains had failed. And, seeking to amplify their voices, FEWS NET and its peers at the United Nations and in Europe issued a joint alert, warning of potential famine.

By December of that year, food aid for half a million Somalis arrived. The next month, 1 million; by February 2017, 2 million. Thanks to the shipments and the many improvements East Africans had made in their own safety net, food prices didn’t spike when the rains failed again. The warnings had worked.

FOUR YEARS LATER, a different teleconnection is playing out, but the picture across Africa is equally grim. In February, in a small UCSB conference room, CHC climate scientist Laura Harrison pulled up a map of Africa. Although there was no El Niño or La Niña to influence events, the two Indian Ocean oscillations she and her colleagues had been watching were going strong.

The blob of hot water off the coast of Somalia turned out to be as hot as it’s ever been, a half-degree warmer than a similar state in 1997. CHC had been right to forecast extensive rains in the Horn of Africa: Moist winds from the blob fueled drenching storms. The resulting flooding and landslides ruined 73,000 hectares of crops and killed more than 350 people. The storms also saturated arid regions, feeding lush growth that lured an unpredicted hazard to the region: a locust invasion. Hundreds of billions of locusts have chewed through rich farmland in Ethiopia’s Rift Valley, while stripping pastures in Kenya and Somalia.

The blob of cold water south of Madagascar was doing the opposite. Just as the team expected, it had dried up rains across southern Africa. On Harrison’s screen, CHIRPS data showed a red blob of anomalous dryness across Zimbabwe—rainfall was running 80% below average for the season. Short-term forecasts called for some rain, but it looked like it would come too late, Harrison said. “The crop has failed in a lot of those areas.”

On the phone from Botswana, Magadzire agreed. He had spent the day training people to use FEWS NET products, and his visiting Zimbabwean students reported lines for maize that lasted hours. To buy it, farmers were selling emaciated cows for a fraction of their value. “There is actually a huge shortage,” he said. In a few days, after the team hashed out its evidence, he’d argue the same to the FEWS NET social scientists who would integrate the data with economic and security analysis.

At the end of the month, FEWS NET staff compared their monitoring with that of their peers at the United Nations and Europe. The combined forecasts would go into the Crop Monitor for Early Warning, a monthly update provided by the University of Maryland that the G-20 group of rich nations began several years ago to unify famine warnings. Already, in response to previous reports, USAID had more than doubled its food aid to Zimbabwe, to $86 million. But even this increase may not be enough.

On 2 April, FEWS NET sent out a rare alert, stating crisis conditions were likely in southern Africa from April to August. Maize supplies would be short, with prices 10 times their normal level. By that time, another danger had arrived: the coronavirus pandemic. The resulting lockdowns in Zimbabwe and its neighbors could exacerbate risks for the neediest, putting them out of work and unable to afford maize. By the end of this year, FEWS NET warned, Zimbabwe could find itself in emergency conditions—one step away from famine.

Reflecting on his time at CHC, Funk is proud of his team and how it has tried to lessen the toll of famines. But he is clear-eyed about a problem that isn’t going away—and may be getting worse, for reasons other than natural cycles. For the past 5 years, during a time of global economic growth, famine threats were still rising, Funk points out. Now, the coronavirus pandemic has the world teetering on recession. He worries that climate change will only exacerbate the inevitable conflicts over stressed croplands. “At the end of the day,” Funk says, “humanitarian crises are caused by humans.”

Fuente: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/04/how-team-scientists-studying-drought-helped-build-world-s-leading-famine-prediction

Users Today : 52

Users Today : 52 Total Users : 35474799

Total Users : 35474799 Views Today : 61

Views Today : 61 Total views : 3574854

Total views : 3574854