By: Julia Rampen.

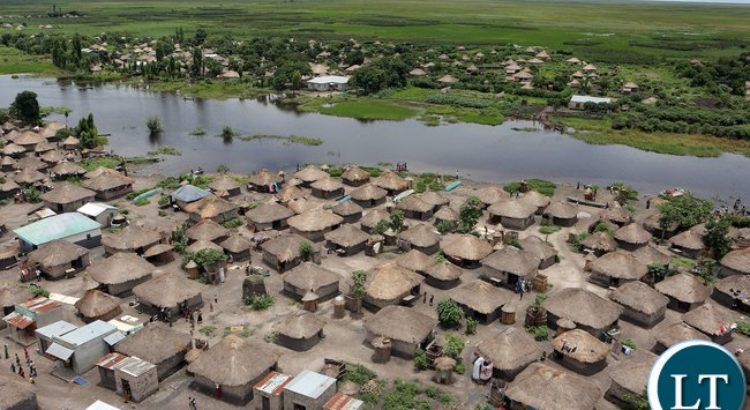

George Mumbi lives in rural northern Zambia, where umbrella-like trees cast shadows on the red earth and there are few roads. The unusual thing about George is that he sent his daughter to secondary school. In Zambia, high schools charge fees, and in George’s community of subsistence farmers most families plough what money they have into educating their sons. But George’s daughter was among those teenage girls who set off from their homes in the bush and began the long journey to boarding school.

Parents in rural districts often prefer their children to live on campus, rather than walk several hours a day or rent alone near the school. They have less control over the journey to boarding school itself. In Kasama, a city in northern Zambia, trains packed with students can be delayed for hours or even overnight. It was on one of these journeys to school that George’s daughter became pregnant. “That’s why she dropped out of school,” he explained, through a translator.

“If you educate a woman, you educate a nation.” In the past two decades, this Ghanaian proverb has become the blueprint for international aid. The commitment to girls’ primary education was enshrined in the UN’s Millennium Development Goals. The UK’s Department for International Development runs the largest global fund dedicated to girls’ education. The charity Campaign for Female Education has produced research showing that for every year a girl is educated at secondary level, her earnings go up, her chances of contracting HIV go down and she will marry later. And if donors are still not persuaded, there’s the promise that she will “resist gender-based violence and discrimination, and change her community from within”.

The message is an irresistible blend of pragmatism and feminism. But while in Zambia most girls receive a basic education, fewer than half go on to secondary school. The biggest issue is fees. But even when this obstacle is removed, there are still additional challenges for girls.

I recently visited Peas Kampinda Secondary School, a short drive outside the sleepy town of Kasama. The school is the result of a partnership between the educational charity Peas (Promoting Equality in African Schools) and the Zambian government. When parents in the local area heard that there was to be a free high school, which would also serve lunch, the prospect sounded so good that they worried there was a catch.

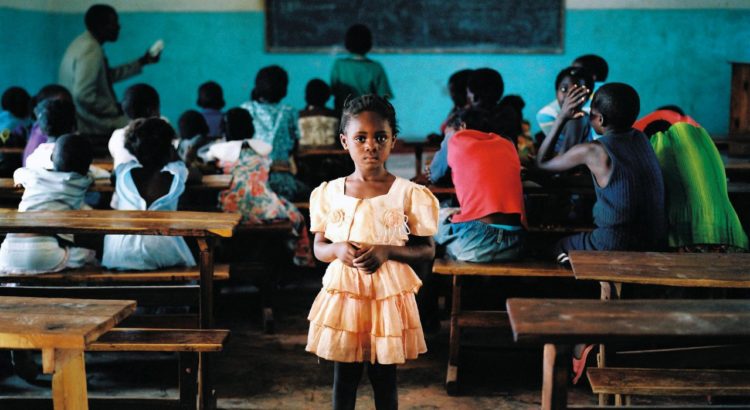

At Peas Kampinda, girls are treated equally. The student body is 51 per cent female, including a cohort who board on campus. But nevertheless, teachers at Peas are aware that expectations are different at home. One girl used to turn up late, while her brother appeared on time. “She was given extra housework compared to the boy,” said Chola Kunda, one of the school’s female teachers, smartly dressed in a black skirt, white blouse and earrings. “After talking to the parents, the situation has changed. That girl is now coming to school on time.” Not only that, but the girl’s parents now ask the brother to clean the house as well. “There’s gender equality in the home,” Chola told me.

Girls who rent rooms nearby face a different kind of challenge: stigma from the locals. “They perceive them as prostitutes,” Chola said. Again, the school intervened, holding meetings with the community to encourage acceptance of the girls.

A girl’s future is even more likely to be set off kilter through teenage pregnancy. At Kampinda, during a student debate, I watched teenage girls stand up in front of a hundred of their peers and argue against sex education in schools. “When a person starts learning about sex, they are going to be concentrating on that subject,” one girl railed. Both sides, though, seemed passionate about the same issue: preventing teenage pregnancies. “No wonder we have poverty in our country,” one defender of sex education lamented. “Because of early marriages and teen pregnancies.”

Zambia is a deeply Christian country, and it is rare to see a school or municipal building that lacks a framed portrait of Jesus. This makes it harder to carry out simple intitiatives such as distributing contraceptives. Legal abortion is difficult to access, and Claire Albrecht, a local aid worker, has encountered many girls who have turned to traditional medicine rather than drop out of school. But such methods are risky. “There was a girl in a village where we stayed. It was her third time, and she died.”

Schools such as Peas Kampinda have had success encouraging young mothers to return to education. But for some girls, dropping out seems the easy option. “I went to school when bullying was at its peak,” Chola recalled. It was an entrenched system that she described as “hell. A lot of people left school because of it.”

But Chola’s older sister was paying for the fees. Having frequently been pulled out of school herself to take care of her siblings, she urged Chola to stick with it. Now 32, Chola is a strong advocate of the Peas child protection policy. “A teacher in this school is very empowered and concerned about protecting children in school,” she said. There is also zero tolerance of corporal punishment.

In the playground at Kampinda, meanwhile, the girls in which so much hope is invested eat their lunch, laugh about boys and ask me questions. “I want to be a surgeon,” one said. “I want to be a lawyer,” another told me. “I want to be a pirate,” a third said with a smile. The girls, mostly boarders, are glad to be at a school where the older years can’t force them to do chores and the teachers won’t beat them up. They have dreams of travelling after school, to neighbouring countries, even to London. “There is a lot of housework [at home], so it’s better we stay here,” said Patience Kabwe, one of the boarders. “We don’t have much time to do that – it’s just half an hour of sweeping. Most of the time we spend studying.”

Source of the notice: https://www.newstatesman.com/world/africa/2019/01/dreams-daughters-how-school-zambia-tackling-education-girls

Users Today : 111

Users Today : 111 Total Users : 35460128

Total Users : 35460128 Views Today : 146

Views Today : 146 Total views : 3418777

Total views : 3418777