Por El Tiempo

Bajos promedios en pruebas Saber indican que se requieren medidas como implementar la jornada única

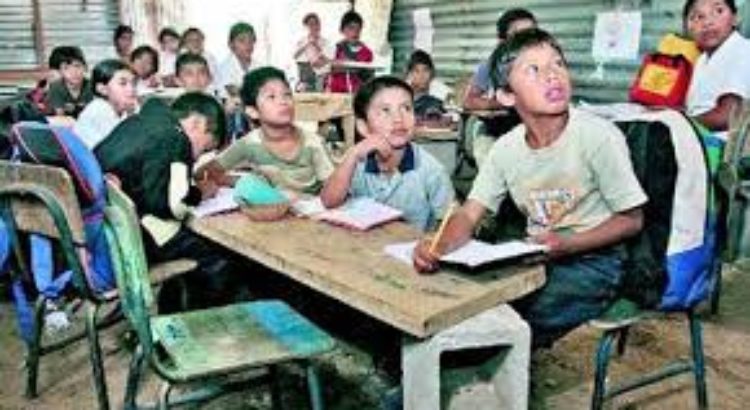

Como la mayoría del país, la región Caribe ha avanzado en la cobertura y calidad de la educación que imparte a sus niños y adolescentes, sin embargo no es suficiente porque tiene rezagos en la cualificación de sus profesores, en la calidad de la educación y cobertura en primera infancia y en los resultados en las Pruebas Saber 11°, 9°, 5° y 3°, que están por debajo del promedio nacional.

Así lo evidencian diferentes análisis de expertos que buscan mostrar las falencias para identificar los retos que tiene el Caribe en esta materia. El estudio ‘Educación escolar para la inclusión y la transformación social en el Caribe colombiano’, de Casa Grande Caribe, es uno de ellos. Esta iniciativa, integrada por varias organizaciones que trabajan por la identificación de inversiones para brindar solución al atraso social relativo de la costa Caribe en cinco áreas, una de ellas educación, plantea que la primera prioridad de la región en educación es aumentar la cobertura y mejorar la calidad de los programas de atención a primera infancia y educación preescolar.

Propone implementar dos grados adicionales de preescolar en el sistema de educación pública y ampliar la jornada única en los colegios públicos de la región. Según la publicación, la transición a la jornada única, que se ha venido implementando desde 2014, está sustentada en estudios que demuestran que la media jornada tiene efectos negativos sobre la asistencia y el aprendizaje.

También plantea una intervención en la formación de los maestros, ya que “la evidencia indica que la calidad de los docentes es uno de los factores principales del aprendizaje, y que hay brechas regionales importantes en este aspecto”. Esta propuesta apunta a mejorar la formación de los nuevos docentes, fortalecer la formación de los que están en servicio y mejorar su nivel de inglés.

Finalmente, recomienda enfilar baterías hacia el fortalecimiento institucional de las secretarías de Educación y de los colegios, lo que incluye programas de acompañamiento a secretarías y formación de rectores. “En total, se estima

que la inversión necesaria para llevar a cabo los programas de esta propuesta es de 2.108 millones de dólares. Esto incluye infraestructura para preescolar y ampliación de jornada única, formación de docentes, fortalecimiento institucional y un ambicioso programa de alfabetización de adultos que se hace en el marco del sistema escolar”, dice el estudio.

Por debajo del promedio nacional Según el Ministerio de Educación Nacional, en 2017 el promedio del Puntaje Global de la prueba Saber 11 para el total nacional fue de 255 puntos, 5 puntos por encima del promedio para el 2014 (que fue de 250). Específicamente para la región Caribe el promedio de la prueba Saber 11 de 2017 se ubicó alrededor de los 242 puntos, lo que significa tres puntos por debajo del promedio nacional.

Entre las 22 entidades territoriales de la región Caribe, solo cuatro se ubicaron por encima del promedio nacional (Montería con 266 puntos, Sahagún con 261 puntos, Sincelejo con 264 puntos y Valledupar con 259 puntos). La entidad territorial con mayor promedio del Puntaje Global dentro de la región fue Montería (11 puntos por encima del promedio nacional), mientras que la entidad territorial con menor puntaje fue Uribia con 49 puntos menos que el promedio nacional. Específicamente, para Lectura Crítica, el puntaje promedio en el 2017 fue 50, cuatro puntos porcentuales por debajo del resultado nacional (54); para Matemáticas 11°, el puntaje promedio en el 2017 fue 47, cuatro puntos porcentuales por debajo del resultado nacional (51); en Ciencias Naturales el puntaje promedio en el 2017 fue 48, cuatro puntos por debajo del resultado nacional (52).

Con respecto a la prueba Saber 3º 5º y 9º de 2017, Barranquilla se destacó obteniendo un puntaje promedio por encima del agregado nacional para las pruebas de Lenguaje y Matemáticas en todos los grados evaluados. En tercero, en la prueba de Lenguaje obtuvo nueve puntos por encima del agregado nacional; mientras que en la de Matemáticas obtuvo diez puntos encima del promedio.

En quinto, en Lenguaje obtuvo siete puntos por encima del promedio de Colombia; en Matemáticas cinco puntos por encima del promedio nacional. Para el grado noveno, en Lenguaje tuvo ocho puntos por encima del promedio para Colombia y en Matemáticas siete puntos por encima del promedio nacional.

“De acuerdo con los resultados, la región Caribe afronta desafíos en todas las áreas de conocimiento, pues el porcentaje de estudiantes en niveles mínimo e insuficiente es superior en comparación a los resultados a nivel nacional. Sin embargo, los resultados obtenidos en las pruebas saber 11 en el 2017 en promedio son consistentes con los resultados obtenidos a nivel nacional”, dice el Ministerio de Educación.

Para seguir mejorando la calidad, agrega esta cartera, es preciso que todas las Entidades Territoriales Certificadas (ETC) continúen implementando estrategias de evaluación formativa periódicas, así como planes que les permitan conocer los aspectos que pueden mejorar y definir las acciones para hacerlo. “Se sugiere continuar implementando autoevaluaciones institucionales y fijando metas que impacten el Mejoramiento Mínimo Anual”, señala.

Igualdad en oportunidades de aprendizaje Por su parte, el Observatorio de Educación del Caribe Colombiano del Instituto de Estudios en Educación (IESE), de la Universidad del Norte, asegura que el principal reto de la región tiene que ver con la búsqueda de un sistema educativo generador de equidad en términos de la igualdad de oportunidades de aprendizaje.

“No solo basta con facilitar las condiciones de acceso al sistema, se requiere un sistema educativo que genere oportunidades de aprendizaje para todos y que dichos aprendizajes sean pertinentes y de calidad. En concordancia con lo anterior, resulta urgente disminuir la proporción de estudiantes cuyo desempeño académico no alcanza niveles al menos satisfactorios”, según el Observatorio.

La entidad agrega que se deben mejorar las condiciones de calidad del servicio educativo, sobre todo en los sectores socioeconómicamente más desfavorecidos, en las áreas rurales y en las zonas con mayor participación de población con necesidades educativas especiales, víctimas del conflicto y pertenecientes a comunidades étnicas.

Users Today : 16

Users Today : 16 Total Users : 35460399

Total Users : 35460399 Views Today : 34

Views Today : 34 Total views : 3419197

Total views : 3419197