- Por: Daniel Sánchez Caballero

Solo un 6% de las personas con discapacidad tiene una titulación universitaria en España, lejos del 40% que tiene como objetivo la Unión Europea para 2020.

La universidad es el gran reto educativo para las personas con discapacidad. En los campus españoles hay 17.000 estudiantes que pertenecen a este colectivo (el 1,7% del millón largo que hay en total), y menos del 6% de las personas con una discapacidad tiene un título, según el III Estudio sobre el grado de inclusión del sistema universitario español respecto de la realidad de la discapacidad, de la Fundación Universia y el Cermi. El dato está lejos aún del 40% que se propone la estrategia europea para 2020. El problema, dicen los expertos, ni siquiera está ahí: la barrera está un poco más abajo, en la Secundaria y el Bachillerato.

“Se va avanzando progresivamente”, explica Isabel Martínez, comisionada de Universidades y Juventud de la Fundación ONCE, consciente sin embargo de que la estadística es pobre. “Pero hay una situación de embudo por los obstáculos que se encuentran por el camino, sobre todo en Bachillerato”, explica. Los datos confirman su teoría. La mitad de los estudiantes con discapacidad no logra ir más allá de este nivel educativo. El 50% nunca intentará siquiera pisar un campus. Con esos mimbres, difícil dar el siguiente paso y subir la tasa de graduados.

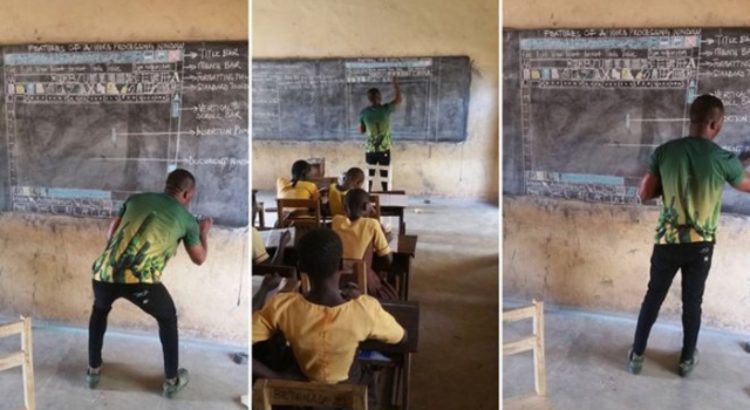

Uno de los principales problemas que se encuentran estos estudiantes se llama adaptaciones curriculares. La falta de ellas, en concreto, según explica Martínez. Los alumnos con alguna discapacidad en ocasiones necesitan que los materiales que se presentan en clase, o los exámenes, se adapten para que puedan acceder a la información en igualdad de condiciones que sus compañeros. Sin rebajar contenidos, se trata de facilitar el acceso. Para un ciego, que no se le presenten por escrito. Para un sordo, solventar su incapacidad de escuchar al profesor. Para un TDAH (Trastorno por Déficit de Atención e Hiperactividad) o alguien con dislexia, que se le conceda más tiempo, por ejemplo.

Sin embargo, no siempre se hace, lamenta Martínez. Aunque se podría pensar que esto ocurre más en la Universidad, un nivel educativo no obligatorio, donde no hay que preocuparse porque todos lleguen, es sobre todo en Secundaria donde se forma el escollo. “Es mucho peor esta etapa que la Universidad. Primero por los recortes en profesores de apoyo, pero también por una falta de concienciación y responsabilidad del profesorado, que es impresentable”, explica. “Gran parte de la culpa de que los chicos no accedan a la universidad viene de aquí”, asegura.

Algo que, en teoría, demostrarían los datos respecto al desempeño de las personas ciegas en Secundaria. Estos chicos tienen una tasa de abandono escolar temprano del 8%, muy por debajo de otras personas con discapacidad y la mitad que el alumnado en general, que ronda el 16% actualmente. ¿Por qué? Según Martínez, solo tiene que ver con el apoyo que estos alumnos reciben de la Fundación ONCE. “Ahí se demuestra que, cuando se dan los recursos de apoyo necesarios los chicos llegan”, explica.

Lo corroboran cuatro estudiantes universitarios con TDAH que participaron en un estudio elaborado por la Universidad de Sevilla. En un colectivo con hasta un 95% de posibilidades de abandonar los estudios universitarios, estos alumnos, casos de éxito, consideraron que lo que les había resultado de mayor utilidad durante su tránsito por el campus fue “la implicación del profesorado”, que conocieran su situación y les ofrecieran las adaptaciones curriculares (no significativas, lo que quiere decir que no se modifican los contenidos, las competencias o los objetivos) que piden los expertos.

Varón y con discapacidad física

Como estos cuatro estudiantes, el perfil del alumno universitario con discapacidad responde a un varón (el 54,4%) con una discapacidad física (46%) que estudia Ciencias Jurídicas y Sociales. La discapacidad menos presente en la Universidad es la sordera. Quizá, como le ocurrió a Juanma, por la (ocasional) falta de apoyos que este tipo de estudiante necesita sí o sí para poder seguir las clases.

La normativa española ampara el enfoque inclusivo educativo que promulga la Convención de la ONU sobre los Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad, a la que España está adherida. El problema, como sucede en general con los asuntos relacionados con la discapacidad, es que no se cumple. En cosas tan básicas como garantizar el acceso, tanto físico como virtual, a todas sus instalaciones, que no siempre ocurre. Que se lo pregunten a Raquel, en silla de ruedas y que ha estado tres años llegando a su clase en el tercer piso de la Facultad de Bellas Artes de la Universidad Complutense porque algún alma caritativa la subía a pulso.

Por ley, este mes de diciembre acaba el plazo por el que tendría que estar garantizado este acceso total para personas con discapacidad, sea a un edificio o a una página web. Sin embargo, este objetivo está lejos de cumplirse.

Con lo que sí cuentan las universidades es con una oficina de atención al estudiante con discapacidad, donde pueden acudir a solicitar las adaptaciones y solventar cualquier problema que les surja. Y cada vez más centros realizan convenios específicos con asociaciones pro inclusión para facilitar el acceso, según explican desde Plena Inclusión, que citan los casos de las universidades de Valencia, Burgos, Comillas o Extremadura.

La última en sumarse ha sido la Universidad Oberta de Catalunya (UOC), que acaba de firmar un convenio con la Fundación ONCE para rebajar sus matrículas. Como universidad a distancia que es, con todas las ventajas que eso conlleva a la hora de facilitar el acceso, la UOC es el segundo centro con más estudiantes con discapacidad de España junto a la Universidad de Valencia y por detrás de la UNED.

Fuente: http://eldiariodelaeducacion.com/blog/2017/11/21/estudiar-en-la-universidad-la-ultima-barrera-educativa-para-los-alumnos-con-discapacidad/

Users Today : 31

Users Today : 31 Total Users : 35474839

Total Users : 35474839 Views Today : 39

Views Today : 39 Total views : 3574907

Total views : 3574907